Peter Urban Gad (1879-1947) is indubitably one of the primary figures amongst Danish film pioneers. His debut film, Afgrunden (The Abyss, 1910) has a place in international film history as one of the earliest canonical works. The film captures the specificities of the medium with innovative camerawork and acting that is consciously directed at the camera lens, breaking with the style of the theatre stage. His career as a director unfolded primarily in Germany in a period when the country was emerging as one of Europe’s leading film nations. He worked with the biggest stars of the era and the most talented cameramen, and he ambitiously developed film language in collaboration with the cinematographers. Throughout his career, he strove to elevate film art and more generally to defend the new and much-criticised medium, as well as to highlight its potential as an art in its own right.

With more than 60 feature films on his resumé and an international ‘big bang’ of a debut, which he both wrote and directed, one would think that Gad’s path to lasting global fame would be a smooth one. But it turned out to be his spouse, and the star of The Abyss, Asta Nielsen, who attracted so much of the spotlight that Urban Gad ended up in the shadows. After his film debut in 1910, Gad worked in Berlin, staying there for about 10 years. In his first three years there, up to the outbreak of the First World War, he directed 31 films with Asta Nielsen. Thereafter, they went their separate ways, but Gad was to direct another 25 German feature films with other stars taking the lead roles. In 1922, he returned to Copenhagen and was appointed to a directorship of the Metropole Theatre cinema, which still exists today as the Grand, on Mikkel Bryggersgade in central Copenhagen. During his life he also wrote several books as well as a long list of articles and columns on cinema, which was clearly his raison d’être.

Despite his productive film career, Urban Gad has been more or less completely overlooked in film historiography. The aim of this study of his life and work is to redress that balance. With Urban Gad’s help, perhaps we can nuance our understanding of a time which seemed to lack the will and the ability to do something with film, something more than selling it by the metre. One reason for the lack of knowledge about Urban Gad is probably that narratives about Danish silent cinema have been focused on mass production and entrepreneurship, that is, the colossal output of the film factories; as well as, of course, on the great film artists Carl Th. Dreyer, Benjamin Christensen and the superstar Asta Nielsen, who is still an object of research today, both here in Denmark and abroad. Another contributing factor is the national perspective that dominates much film historiography. Urban Gad was a cosmopolitan. He ventured abroad, where the level of professionalism and artistry quickly overtook the Danish production context. When he died in 1947, no-one wanted to be associated with Germany, and that may be another reason why the story of his German film adventure and his contribution to cinema remains untold.

This article introduces Urban Gad and accounts for his formative years: his upbringing, his education and development, and his film debut in Denmark. We will thus gain a sense of the baggage he took with him to Berlin in 1911, where his film career took off in earnest. What kind of skills had he learnt in Copenhagen cultural circles and the bourgeois life of the 1900s? How did someone train themselves up in that hectic and scintillating film milieu, in which experience with the new medium was accumulating from one day to the next, and only very few people knew anything more than anybody else because it was all about experimenting with new tools — in an artistic sense as much as a commercial sense.

In the shadow of two strong women

Asta Nielsen and Urban Gad were creative partners in the period 1910-1914, as well as a married couple, and companions. It is first and foremost Asta Nielsen who retrospectively defined Gad’s contribution to cinema; in interviews, in her memoirs, and most recently in the rediscovered ‘secret’ telephone conversations of the 1950s.1 In her memoirs, published in 1945-6, she mostly glosses over him, and in interviews and elsewhere, she minimises or even insults his efforts:

Urban Gad’s films were always shit. They were wonderful assignments, it was his talent that he could write big roles for me. He could give me a brilliant canvas to work with. His great talent, and my great chance. He couldn’t tell me anything, he couldn’t tell me how I should be. Nobody wanted to hire him, but I always insisted he should come along.2

In her own self-understanding, she was the creative force that crafted and unleashed the film narrative in a sublime interplay with the camera. Her director and collaborator, Urban Gad, is pretty much omitted from the story. But 10 years ago, professor of Scandinavian Studies Stephan Michael Schröder of the University of Cologne directed a more nuanced gaze at Urban Gad in the article “Und Urban Gad? Zur Frage der Autorenschaft in den Filmen bis 1914” (“And Urban Gad? On the Question of Authorship in Cinema up to 1914”). He compares Asta Nielsen’s claim that her scenes were only roughly sketched in the manuscripts (what she calls “a brilliant canvas”, above) with the actual descriptions of scenes in surviving screenplays. Schröder’s study shows that the scripts contained thorough descriptions of scenes, not to mention the protagonist’s feelings and actions, and he concludes that this is a case of “…a collaboration in which Urban Gad plays a much more meaningful role that he has hitherto been given credit for.” (Schröder 2010: 210)3

There is, then, evidence that Urban Gad, who both wrote and directed, left his distinctive mark on the finished films. In her book Maske og menneske — Asta Nielsen og hendes tid (2019, ‘Mask and person — Asta Nielsen and her Time’), Lotte Thrane builds on Schröder’s critical reading and berates the generally uncritical tone of research on Asta, whereby “…Asta Nielsen’s own pronouncements (which are carefully referenced) have been presented to countless readers without the material being interrogated.” (Thrane 2019: 61). Thrane presents an interview of 1928, in which the diva actually speaks in positive terms of her first director and ex-husband: “Urban Gad definitely did his best, he conceived all the screenplays and wrote them himself and stimulated me in many different ways.” (Berliner Zeitung am Mittag, 29 September 1928, cited in Thrane 2019: 59). But in best Asta style, her comment is followed by a “but”, so that she can highlight her own delightfulness and reduce Gad to a bit part player in the story.

However, it was not only Asta Nielsen who consigned Gad to the shadows. His mother was also a prominent figure: Emma Gad has been more or less immortalised by her 1918 book Takt og Tone, a classic Danish handbook of good manners and social refinement which has been re-published many times over the years. But Emma Gad was much more than an author and expert on etiquette. She was also a particularly pushy mother and an endless source of inspiration for her son, and she is thus key to understanding how the young Urban was educated and shaped into the artist he became. Bjarne Kildegaard’s biography of Mrs Gad, Fru Emma Gad (1984/1992), provides insight into her son’s upbringing.

Family and cultural formation — in a bourgeois citadel

Urban Gad was born in the coastal town of Korsør on 12 February 1879. His father, naval officer Nicolaus Urban Gad, had been stationed there and for the next five years he piloted the postal ship between Korsør and Kiel in Germany. His mother Emma was not particularly fond of Korsør, nor of her life as a housewife. She began to write in secret when she had time, and debuted as a dramatist in 1886.

A change of jobs for the father entailed a move back to Copenhagen for the family, and, after a couple of temporary stays in the districts of Nyboder and Christianshavn, in 1894 they moved into a stately 10-room apartment at number 40 Dronningens Tværgade in the centre of town. For many years, this address played an important role in a lively chapter of Copenhagen’s cultural life — with Emma Gad as its centre of gravity. At that point, Urban Gad was around 15 years old. His brother Henry Christian, his senior by 5 1/2 years, followed in their father’s footsteps and embarked on a naval career at a young age. Both father and son were away for long periods, in winter as well as summer. In their absence, Emma Gad developed a tight bond with her younger son. In rhythm with the seasons, they moved back and forth between the city-centre apartment and the family’s summer house near the coast at Humlebæk, and thus lived out the so-called ‘double home culture’ that was common among the more well-to-do. In 1897, Urban Gad was 18, and graduated from Borgerdyd high school in Helgolandsgade in central Copenhagen.

Artists, authors and politicians met regularly for social and intellectual gatherings in the Gad home, whose sitting rooms were decorated in so-called klunkestil, a turn-of-the-century style named for the numerous tassels that punctuated its swags and drapes. This was where the cultural elite of Copenhagen met, including names such as the brothers Georg and Edvard Brandes; the author Gustav Wied; Peter Nansen, director of Gyldendal publishing house; the painter Fritz Thaulow; the actor Poul Reumert; the editor-in-chief of the newspaper Politiken, Henrik Cavling; the actress Karina Bell; as well as baronesses and members of the royal family — just to name a few. An exquisite mix of intellectual social critics, influential opinion formers, the bourgeoisie and creative artists. Georg Brandes was the undisputed crown jewel of Copenhagen high society, and Emma Gad was positively immodest in her use of attractive young women to spice up her invitations. For example, one of her tea salons was announced with the heading “A Waltz through Time” and was to feature songs by Gerda Hartmann (Weber, Lemmer, Schubert, Chopin, the Strausses, etc.), and a dance performed by Mrs Judith Hansen, Miss Karina Bell and Royal Ballet dancer Mr John Andersen. Emma Gad wrote to Brandes: “I think that it will be lovely — maidens whirling around to murmuring waltzes — and many beautiful ladies in the audience.” (Kildegaard 1992: 102).

That she was such an enthusiastic hostess at home in the apartment also established a widely branching network of contacts for the family, and thus access to influential individuals. Emma Gad directly addresses this, for example in this letter to Peter Nansen:

Do you not miss Gerd and the rest of us? If you are longing to see us, then do come and help yourself to a prawn sandwich on Friday evening, the 14th. I have just invited Tage Bull and Gerd’s newly appointed director Davidsen from Nordisk [Films Kompagni]. One has to ingratiate oneself with those in power, however one can. (Undated letter, probably 1913, cited in Kildegaard 1992: 109).4

Emma Gad — mother and lifelong friend

Dear Peter Urban! It says somewhere in this book that one must try to find one’s best friends from within the family. This is the happiness I have found with you, all at once my son, my friend and my advisor. Thank-you. — That this book has come into being is all thanks to you. (Kildegaard 1992: 125)

This dedication is taken from the very first edition of Takt og Tone, which Emma Gad dedicated to her son when the book was published in 1918. She represents the conservative and culturally-dominant values of the time, ideals which had dominated the upper middle classes of the nineteenth century, but also a new and modern reality, not least as regards women’s lives and possibilities. Urban Gad’s close relationship with his mother was to shape most of what he did in the first decade of his adult life. She was an intensely engaged person and worked as a playwright, as a permanent writer for the influential daily Politiken, authored many books and was not least the architect of the very active social life she hosted both in the city and in Humlebæk. Moreover, she was engaged in improving women’s living conditions and rights through extensive work with associations including the Copenhagen Women’s Reading Association and the Women’s Commerce and Administrators’ Association (an evening club for single working women known as ‘Hegnet’, or ’The Fence’); she was a founder of the Danish Playwrights’ Union and the Ladies’ Morning Club, which grew into a project facilitating the exhibition of applied arts, called Dansk Kunstflidsforening.

Urban Gad shared many of his mother’s interests. They travelled together, they worked together, and they wrote together. And it is probable that Emma Gad, thanks to her network and prominent position, was able to pave the way for and influence her son’s slightly fumbling career. He kept his bedroom in the apartment on Dronningens Tværgade, and it remained at his disposal until the property was re-modelled several years after Emma Gad’s death (Kildegaard 1992: 124). She died on 8 January 1921, and in private letters from her relatives it transpires that Urban Gad declared the whole year to be a year of mourning:

He refused almost completely — causing a range of difficulties and problems for those around him — to do anything for a whole year other than whatever furthered the cause of sorrow and mourning. (B.T. 30 December 1922)

A year after her death, Urban Gad articulated his feelings for his mother: “She was my only friend, my comrade, ever since I was born. Her absence is unfathomable to me” (B.T. 30 December 1922).

Painter and craftsman

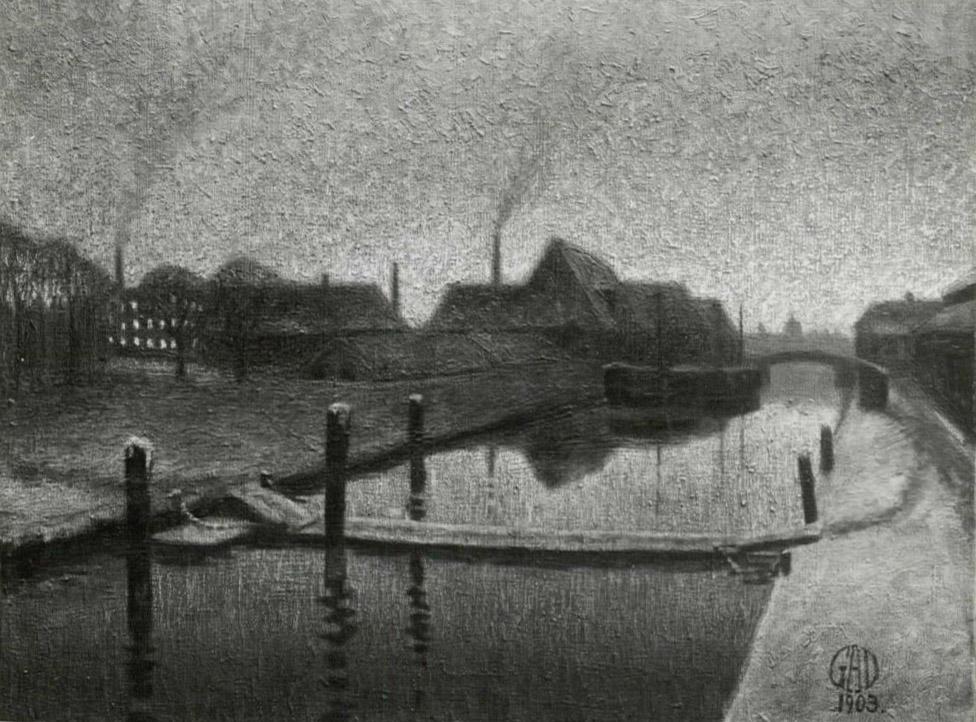

Throughout the 1900s, Urban Gad developed and educated himself as a craftsman and painter. In November 1901, a newspaper reviewed an exhibition held by Dansk Kunstflidsforening, the arts and crafts club founded by his mother, and it seems that Urban was already progressing as an artist. Amongst the exhibitors were Harald Slott-Møller, Hans Tegner, and of course Urban Gad, who had contributed with “a selection of artefacts, including some fine screens, pillows and wall decorations, which were bought this year by the Museum of Industry and the painter Fritz Thaulow” (Nationaltidende, 14 November 1901).5

Precisely when he started to paint is unknown, but he was trained by the Norwegian Fritz Thaulow in France. Thaulow was a professional painter and a relative of Urban Gad’s father.6 On 19 March 1902, Urban and his mother travelled to Paris. Just five months later, the magazine Dannebrog published an announcement that “The painter Urban Gad, who has studied in Paris, has returned to Denmark to convalesce after an attack of rheumatic fever.” (Dannebrog, 12 August 1902). A year later he was back, this time in the south of France, invited by Thaulow (Dannebrog, 17 September 1903).

At the time of his departure, his paintings were publicly exhibited for the first time in a gallery on Højbro Plads, by two gentlemen called Winkel and Magnussen. The debutant was able to take the following verdict with him on his travels:

Mr Gad…is undoubtedly in possession of talent. The paintings ‘Spring Day’, ‘Red Roofs’, ‘The Old Tollbooth’ and especially ‘Spring Rain’, all with motifs from the South of France, encapsulate no little atmosphere and artistic charm. But there is also undeniably some looseness and uncertainty there.

Furthermore, the reviewer recommended that the young artist should leave the French-Norwegian school behind and turn his attention to the nature of his homeland (Dagens Nyheder, 24 September 1903).

Just before Christmas 1903, Urban Gad found himself back in Copenhagen after what would probably be his last stay in France. In the company of Fritz Thaulow he had been able to meet many of the great personalities of the period, very much as he had in the apartment on Dronningens Tværgade. Thaulow’s bohemian home and atelier at 21 Boulevard Berthier in Paris was an eccentric but exclusive meeting place for artists, patrons and other luminaries — including Anatole France, Auguste Rodin, August Strindberg, Herman Bang and Georg Brandes (Kildegaard 1992: 122). Gad’s impressions of French life found their way onto his canvas, and his paintings were exhibited with increasing frequency, but opinions on his talent were mixed. In 1905 he took part in the March Exhibition at the gallery of art dealer Valdemar Kleis at 95 Vesterbrogade, at which over 100 other artists were represented.

He was dealt this blow by a reviewer in Dannebrog:

Peter Urban Gad is as yet immature; in the two pictures ‘Fritz Thaulow painting’ and ‘Dusk’ he shows the direction in which his abilities are heading, when he is calm, but in several others. e.g. the Copenhagen picture, his talent has taken an unfortunate detour, and the fragmentation and colour have taken over, at the expense of harmony. (Dannebrog, 28 February 1905).

And in another newspaper:

That he is talented cannot be argued with; but the colours on his palette are still higgledy-piggledy. He is not yet in control of them; and in most of his works he is out on the seas of untruth. What kind of Copenhagen street scene is that, for example? It looks like it is covered in fish scales. His motifs from the south of France are far better and more consciously handled. (Samfundet (København), 27 February 1905).

That April, Urban Gad was among the artists at the exhibition ‘Rejected from Charlottenburg’ (a kind of Salon des réfusés), and later the same year he contributed two “good atmospheric pictures” to Kleis’s Autumn Exhibition, “…one of them from Copenhagen Harbour, and the other from Humlebæk” (Berlingske Aften, 11 October 1905). He continued to develop his painterly vocation with a stay in the town of Ribe in summer 1906, but after that there is no evidence of further activity. Could it be because Thaulow died in November 1906? Did the reviewers take the wind out of the young painter’s sails, or was he himself in doubt as to whether he had chosen the right form of expression?

Exhibition scenographer and practical Jack of all trades

During his apprenticeship as a painter, Urban Gad also continued throughout the 1900s to help his mother with her myriad of exhibition projects, not least for Dansk Kunstflidsforening, the exhibition club for amateur practitioners of the applied arts. In that organisation’s first year, he was particularly active in the sketching room 7 (Kildegaard 1992: 163-164).

He also contributed to creating the decoration and set-up of the premises for the Tulip Exhibition in May 1900, the Tropical Fruit Exhibition in October 1900, Dansk Kunstflids Exhibition in November 1901, the East Asian Exhibition in September 1902, the Housekeeping Exhibition in October 1903 and the Colonial exhibition in the Tivoli Gardens in June 1905. Although after the Heiberg Exhibition8 in November 1909 he said goodbye to his mother and her exhibitions in favour of an appointment with the Dagmar Theatre, Emma Gad was quick to praise her son ’s efforts:

…and if my son Peter Urban Gad, who in his youth wanted to be a painter, had not worked like a Trojan to help me to create a stock of paintings without ever getting a penny for them, and had he not given me artistic advice and daily counsel for that same wage, it would have been impossible for me… (Emma Gad, Chair of Dansk Kunstflidsforening 1900-1911, extract from leaving address, 1911). (Kildegaard 1992: 154)

A ‘change of scene’ was underway in Urban Gad’s life, but there is much to suggest that his creative bent and the joy he took in using his hands had by no means run dry. This was in evidence again much later in life, more precisely in the summer residence at Humlebæk, to such an extent that in 1936 a columnist declared him a “Champion Tile-Caster” and let the readers witness this with their own eyes. For behind bright blue gates with golden lion heads lay a garden that was

… designed according to his own sketches — and decorated with very large and beautiful tiled areas, for which he himself has cast each and every tile (…) What Urban Gad can do with concrete tiles is simply enchanting. One can see that he was a painter before he began to make films, and he can make the tiles shine in all the colours of the rainbow, so that they make strange and pretty paths between the many Chinese and Indian bronze and ceramic sculptures, which he brought home from his great trips to the East. (Berlingske Aftenavis, 26 November 1936)

Enchanting poetry and an epic urge to create were apparently bubbling lustily up at this point in the now middle-aged cinema manager’s life. His work with the colourful homemade tiles nuance the image that Urban Gad had accrued by the mid-1930s, of a serious cinema director in sharp suits, shaking hands at official events and receptions.

Stage plays — research, employment and debut as a dramatist

In an announcement dating from the end of August 1907, one could read that the young painter “…has for quite some time now been carefully studying how theatres overseas employ ‘painterly’ staging, lighting techniques, costumes etc….” and furthermore that he was now about to undertake a new study tour with the same aim (Berlingske Aften, 28 August 1907).

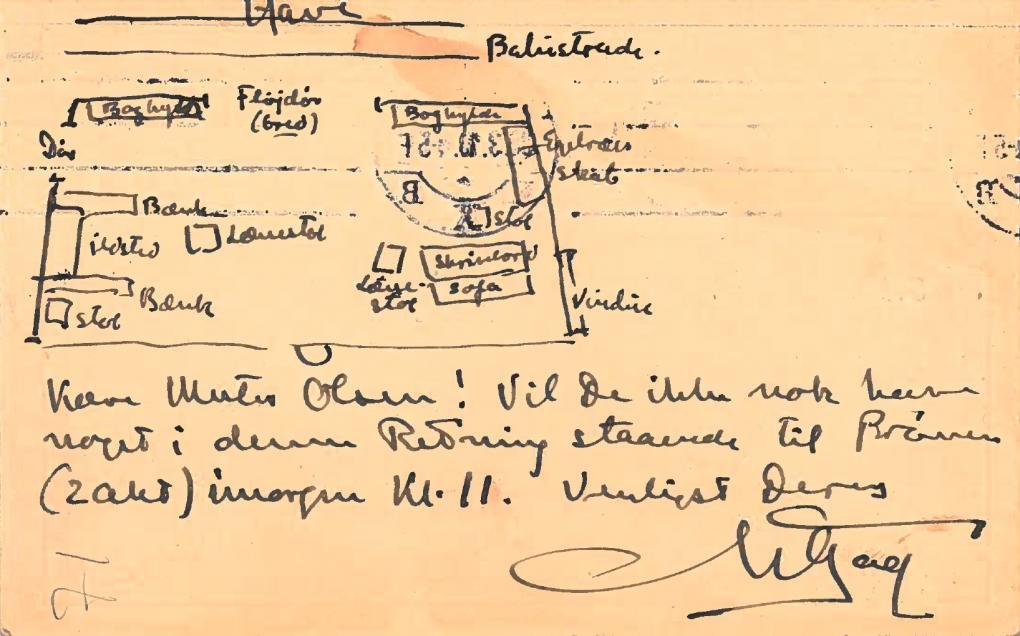

A change of artistic tack is on the way, and it would not be more than a year before Urban Gad’s research was converted to practice in a production at a newly-established Copenhagen theatre. On 19 September 1908, The New Theatre, led by director Viggo Lindstrøm, opened its doors to the public. Its opening show was ‘Den skønne Marseilleanderinde’ (The Lovely Marseillaise), in which Gad’s future film buddies Miss Asta Nielsen and Mr Poul Reumert would perform. Gad commented in an interview two days before the opening that he was

… in the process of developing a position (…) which the Germans call ‘künstlerische Beirath” or Artistic Advisor. Everything which the stage director cannot look after in full measure (…) That is, the decor, the lighting, etc. Painting in a scenographic sense will in other words be his canvas on the easel of The New Theatre. (Nationaltidende, 17 September 1908)

Another newspaper characterises his position as “Inspicient” (a term roughly translating to stage manager) but regardless of the job title and how he had got it, Urban Gad had a new career.

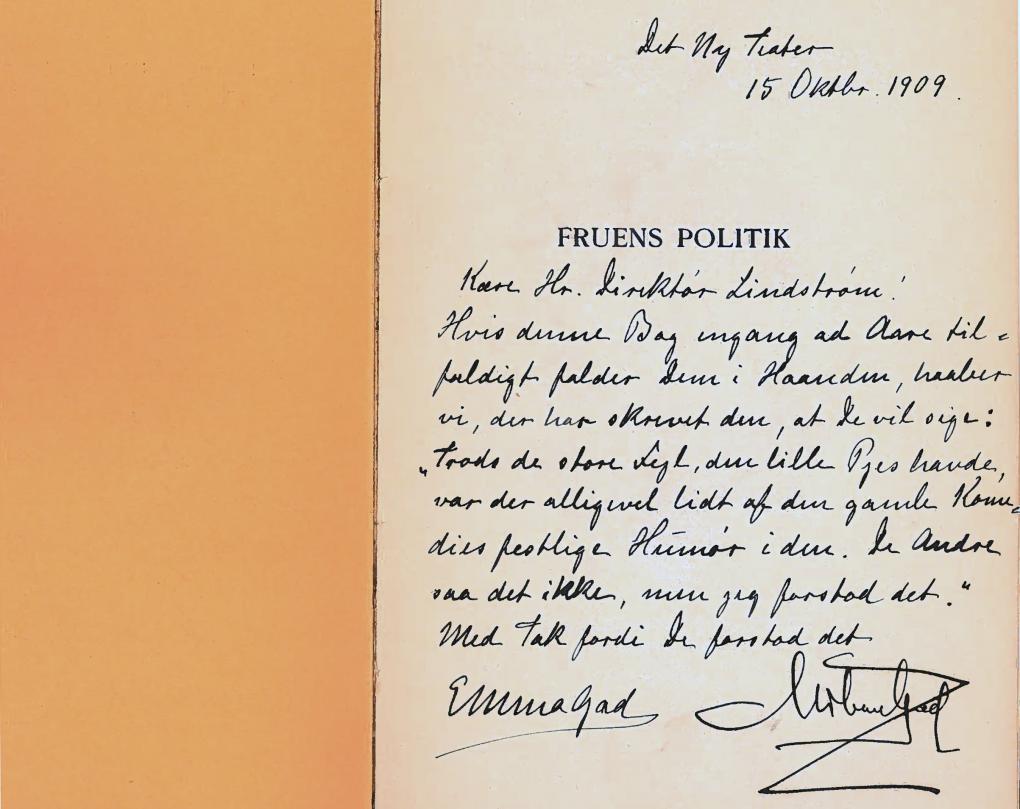

At the same time as the study tours and the appointment at The New Theatre he ventured to write his first dramatic work. In collaboration with his mother, he wrote the light play ‘Fruens Politik’ (‘The Politics of Wives’), which he also staged.9 Two husbands are unfaithful to their wives, both of them are caught. One wife makes a fuss, the other keeps her counsel. Which of them is cleverest? Both Poul Reumert and Asta Nielsen performed in the play — in her case in a minor role.

The play opened on 15 October 1909, and the reception was mixed, bordering on decidedly negative. Perhaps expectations of this particular pairing of dramatists had been too high; in any case, several reviewers commented that the play fell below Emma Gad’s usual standard. The newspapers Folkets Avis and Aftenbladet were positive, but Dagens Nyheder wrote of a “fragmented impression” and differentiated between the experienced mother and debutant son, who had perhaps had responsibility for the dialogue. The reviewer in København found the play un-amusing and mourned the previous production, ‘Dollarprinsessen’ (‘Dollar Princess’), which had been a big hit. Jyllandsposten pulled no punches: “a childish play” and “some of the thinnest nonsense ever seen on the Copenhagen stage”; it was “impossible for the actors to enunciate the Gad-esque lines so that the audience could understand them” (Jyllandsposten, 17 October 1909).

The reception must have piqued the writing team. Emma Gad wrote to Georg Brandes on 16 October:

It made me and my young collaborator so happy that you enjoyed our little play. Yes, I also think that the piece has been harshly and unfairly received, since it had no pretensions to be anything but a light farce, and I only wish that you would write a good word about it, somewhere or other, when you have the chance. I don’t think it is right or nice of Mr. Lange to do his best to take the wind out of a young man’s sails; whatever else one can say, he has certainly shown he can write with humour. We certainly don’t have too much of that. (Kildegaard 1992: 130)

Emma Gad is referring here to Sven Lange, the powerful and much-feared theatre and literature critic at Politiken, who succeeded Edvard Brandes in 1904 as the paper’s chief theatre reviewer. He was actually not so rude as a couple of other reviewers, but remarked that “…the moral of the story was over-sugared by the usual Gad-esque oddities…” (Politiken, 16 October 1909). But the ‘lion mother’ steps up for her son and even nudges Georg Brandes to intervene.

Whether Urban Gad was just disappointed, or got a job offer he couldn’t refuse, we can only guess. In any case, a couple of weeks after his debut as a dramatist at The New Theatre, he moved to the Dagmar Theatre on Jernbanegade. He was hired as a stage director, and on 13 April 1910 an English detective drama opened with Valdemar Psilander and Augusta Blad in the starring roles.

The reviewer in Dannebrog was not thrilled — the moral of the play was weak and its logic was no better — and the production had a very short run. Things were not going well at the Dagmar Theatre either. On 10 May, there was a crisis meeting of the management and staff. Director Walter Christmas resigned, and so did Urban Gad. His final contribution to stage art was the decor and costumes for the production of a 300-year-old school comedy, ‘Karrig Niding’, which was staged with young students in the roles in the courtyard of Regensen collegium in central Copenhagen on 27 May 1910.

His work in the theatre and in exhibitions had armed the young artist with some very important skills in relation to the film work he would soon undertake. He had worked with stage space, decor and directed actors. He had familiarised himself with lighting, both in gallery spaces and on stage. He had written plays, that is, learnt to think using dramatic materials and narrative technique, as well as managed several theatre productions. What was missing was experience with a camera, but Urban Gad’s training as a painter furnished him with knowledge of image composition and perspective. In fact, in retrospect, the newspaper B.T. discerned a glimpse of the filmmaker Urban Gad in the much-maligned theatre play he had written with his mother:

We remember a comedy which he wrote for The New Theatre, together with his mother, the Lady Admiral. It was called something like ‘Women’s Politics’. In that comedy emerged the first signs of the path on which Urban Gad was about to set out. On a rolled-down projection screen a shadow scene played out, in which two lovers’ respective preferences were revealed in an unequivocal manner. This was, in its own way, Urban Gad’s first film. (B.T., 25 October 1919 in connection with the publication of Gad’s book Filmen — dens Midler og Maal, or Film: Its Tools and Language).

Film experience and dream debut

The widespread assumption about Urban Gad’s debut film is that it was The Abyss. But in fact, even before that, he was involved in the production of the Kinografen company’s En Rekrut fra 64 (A Recruit from 64), based on Preben Rist’s novel of the same name. A Recruit premiered on 1 August 1910, that is, just a month and a half before The Abyss. It was an ambitious historical film that was both expensive (Schröder 2019: 235) and demanding to shoot, with over 200 extras in historical costume and big battle scenes — quite the baptism of fire for a novice. The live fire from the German batteries was created by laying long iron pipes down in a ditch, from where hefty portions of flour were shot out at regular intervals (Biograf-Bladet, 1 November 1931).

There are several versions of Gad’s role on the film. According to the daily København (2 August 1910), “…Mr Urban Gad has composed the [illegible] exciting plot…”. Politiken credited him with having “…stitched the individual scenes together and tightened the threads, so that a real play has emerged from the whole…” (Politiken, 3 August 1910). Both comments could be read as indicating that he wrote or co-wrote the manuscript. Stephan Schröder does not accord Gad any big role in the film’s genesis, arguing that no-one would put such an expensive production in the hands of a filmmaker with no experience (Schröder 2019: 252).10 The truth is probably that A Recruit from 64 was made in collaboration between the producer Alexander Christian and the cinematographer Alfred Lind, who were the only members of the crew with any experience, and Urban Gad. It transpires from an accounts book showing payments for expenses and wages that Gad received 150 kroner for “assistance with the shoot”.11 Unfortunately no fees for Lind and Christian are mentioned, so there is no point of comparison.

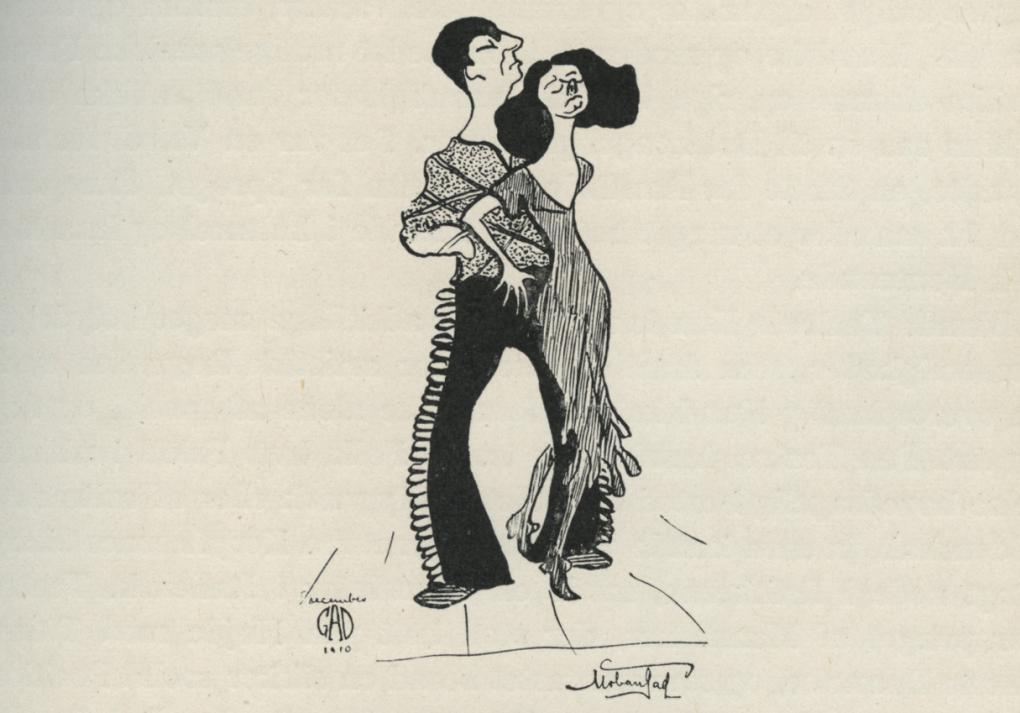

Urban Gad had developed a taste for cinema — and for Asta Nielsen. In the first instance, he was interested in her talent, for he had discerned her unfulfilled potential from working with her at The New Theatre. He wrote a screen role for her and with entrepreneurial enthusiasm they made the film that was to become an artistic and commercial mega-success. The Abyss premiered on 12 September 1910, and was Urban Gad’s debut as film director and screenwriter. Similarly, it was the screen debut of Asta Nielsen, Poul Reumert and Robert Dinesen, and Gad’s close friend, the cinema manager Hjalmar Davidsen, financed what was an economically daring project. The film became a veritable cannonball of a launch for Gad’s and Nielsen’s careers. Perhaps this was not all that clear to them, for Asta Nielsen related that after great success of The Abyss, Urban Gad tried to get her a contract at the Casino Theatre and asked the director there to adapt the film into a popular stage comedy. The director was willing, but he didn’t want Asta in the role — so she stuck with her contract at The New Theatre, which did not give her much to play with in the way of parts (Dagbladet, 18 March 1916).

The theatre work was, though, a closed chapter, because The Abyss triggered an avalanche. For Asta Nielsen and Urban Gad, the avalanche came in the form of gilt-edged contracts and exorbitant fees. And for the film’s producers, whose eyes were opened to Asta Nielsen’s distinctive talent and the pull of the star as a marketing tool. In Germany, the cinema market’s existing business models were overturned with the premiere of The Abyss in mid-November. Amongst other things, the cinemas introduced the practice of screening the film as a standalone programme, so that it could run every hour. Until then, programmes of two hours had been the norm, combining several short films and a main film. Not only was The Abyss a big enough hit to function as an attraction in its own right, it also brought with it a more lucrative business model, in that the ticket price for a one-hour programme was the same as for several short films, and thus underpinned a doubling of cinema income (Loiperdinger 2013: 93-97).

The Abyss was also innovative in an artistic sense. Film sceptics were confronted with the new medium’s artistic potential: something new was afoot here as regards acting, camerawork and even the staging. True, the erotic triangle with passionate scenes, the seductive gaucho dance and a dramatic murder scene all appealed to the young bucks in the audience as well as to their lady friends. But the film’s opening sequence attests to ingenuity and a talent for creating a dynamic image: the encounter between the two young people, Magda and Knud (played by Robert Dinesen) takes place on the rear platform of a tram.

Film clip: Tram ride. Afgrunden (The Abyss, Urban Gad, 1910).

The camera is positioned on another tram following closely behind, so that the interplay between the two actors is enhanced by the city life that whirls past during the trip.

The gaucho dance, the erotic keystone of The Abyss, is also filmed with an acute awareness of the cinema audience, who are watching from a completely different angle than the theatre audience implicit in the scene itself (outside the right-hand frame of the picture, behind the orchestra); in turn, the fictional theatre audience does not see what the cinema viewer sees. In his own way, Gad manages to accentuate the distinctive perspective which the camera can offer the viewer — with Asta Nielsen playing directly to the camera and thereby to us, the cinema audience. Indeed, Poul Reumert remarks in his memoirs that during rehearsals for the dance, with choreographer Anna Jeanette Tardini,

…Urban Gad arrived and suggested changes that resulted in Asta Nielsen’s and my dance becoming a little drama in its own right. (Reumert 1940: 53)

Just imagine Gad while the dance is being filmed: “Tie him up! Untie him! Bite him!”

Film clip: The gaucho dance. Afgrunden (The Abyss, Urban Gad, 1910).

Finally, the drama’s concluding scene is staged to great effect. Magda, who has just murdered her lover Rudolph (Reumert), is led by a policeman down the steps on the left of the screen, walking like a rag doll, step by step in a long take. Once on the ground, at the viewer’s eye level, she crosses through the picture and into our field of vision. A woman who is dissolving, apathetic, finished. With good reason, the scene has entered the cinematic canon.

Film clip: The closing sequence. Afgrunden (The Abyss, Urban Gad, 1910).

In just a few months, the new film couple had signed contracts with no fewer than three big production companies in Aarhus, Berlin and Valby.

1911 — a hectic year of work

After the success of The Abyss, things moved fast for the Nielsen-Gads. Frede Skaarup, the director of Fotorama in Aarhus, hired Asta Nielsen for as many roles as she could manage to shoot in July and September. The fee was 5000 kroner and the fine, should she breach her contract, was double that. The contract was signed on 2 May 1911, but even before that, the film Den sorte Drøm (The Black Dream) had been shot in the space of a couple of weeks in April. Urban Gad was the writer and director, and this was another dramatic love triangle with hot kisses and a deadly outcome, this time with Valdemar Psilander as a Count and lover number 1, while the Aarhus actor Gunnar Helsengreen played his scheming rival, the jeweller Hirsch. The film’s Danish premiere took place on 4 September 1911. In this, his second film, Gad demonstrates lovely framing by using curtains in a doorway, a treacherous mirror as a fourth wall in the image, and cuts to medium shots and out again, all of which effectively intensify the drama.12

Film clip: The treacherous mirror. Den sorte Drøm (The Black Dream, Urban Gad, 1910).

He may have borrowed the mirror effect from the film Ved Fængslets Port (Temptations of a Great City, August Blom, 1911), which had premiered that March and can be regarded as Nordisk Films Kompagni’s consolidation of the ‘long film’ format after a first attempt the previous August with Den hvide Slavehandel (The White Slave Trade, August Blom, 1910). Temptations of a Great City was also Valdemar Psilander’s breakthrough film and one of the company’s big successes to date. Director August Blom, with Axel Graatkjær 13 behind the camera, had innovated with a mirror scene that reveals the main character’s trustworthiness, without him knowing it. On the other hand, the close-ups in The Black Dream were unheard of, and the fact that the camera moves closer in towards the action creates a hitherto unseen intensity in the drama. The film’s cinematographer, Adam Johansen, was a blank slate, having apparently only ever made a handful of films, of which The Black Dream seems to have been his first. The result of these two novices’ work has to be regarded as surprisingly successful and should not be under-estimated, if we want to understand Urban Gad’s pioneering contribution in a film-historical context.

But before the shoot in Aarhus, Gad and Nielsen had been filming in Berlin. The Deutsche Bioscop company hired the couple to make 10 films. They signed the contract and made the first two, Heisses Blut (Hot Blood) and Nachtfalter (Moths), during the spring of 1911 in a little studio at Chausseestrasse 123 in Berlin. The other films were to be shot during the summer and autumn months. But the whole German arrangement was upset when a new stakeholder arrived on the scene. An Austrian film distributor, Christoph Mülleneisen, had seen The Abyss and conceived the idea of setting up a company which would have a monopoly on Asta Nielsen. There was a hectic and dramatic round of negotiations, ending in an agreement that another German distribution company, Union (or PAGU) would also participate in a consortium, which would produce Asta Nielsen’s films over the next three years, with Urban Gad as director and writer. The company was named International-Film-Vertriebs-GmbH.14 In total, 31 films were made, until the outbreak of the First World War put a stop to production. Urban Gad’s account of the advent of the war in Berlin can be read in Kosmorama #256 (Danish only): Flugten fra Berlin.

But another couple of contracts remained to be honoured, and these led Nielsen and Gad to Nordisk films Kompagni in Valby, outside the Danish capital, before they moved to Berlin. As Fotorama and Nordisk had joined forces in a joint stock company on 8 May 1911, just six days after the agreement between Asta Nielsen and Fotorama was signed, the engagement moved to Copenhagen (Thorsen 2013). The result was just one film, Balletdanserinden (The Ballet Dancer), with August Blom as director. It was shot in May 1911, and Asta Nielsen got 5000 kroner as an honorarium — a fee that was unheard of at that time. In comparison, the highest-paid actors at Nordisk (Adam Poulsen, Johannes Poulsen and Augusta Blad) received 350 kroner per film. After The Ballet Dancer, Asta Nielsen was released from the Fotorama/Nordisk contract, and the fine of 10,000 kroner was paid off, probably by Mülleneisen.

As for Urban Gad, in 1911 he directed three films for Nordisk Films Kompagni. We know from film historian Isak Thorsen’s research that Gad had signed a contract in Aarhus with a company called A/S Københavns Kunstfilms Kompagni, which was controlled by Fotorama. This contract, dated 8 April 1911, also fell under the merger with Nordisk Films Kompagni, with the result that Gad was obliged to make up to 12 films at the Nordisk studios in Valby (Thorsen 2013). It was a case of straightforward directing; the screenplays were already bought and so ‘just’ had to be brought to the screen. The first three films, all dated 1911, were Dyrekøbt Glimmer (When Passion Blinds Honesty), Den store Flyver (The Amateur’s Generosity) and Gennem Kamp til Sejr (Through Trials to Victory). They seem to have been shot during September and October — Urban Gad was paid a monthly fee of 500 kroner for those two months15 In 1912, he directed only one of these contracted films, Det berygtede Hus (The House of Ill Repute) also known as Den hvide Slavehandel III (The White Slave Trade III), for which he was paid 500 kroner in March of that year..16 An extensive correspondence between Gad and the company in March 1912 bears witness to Gad’s wish to end the contract earlier than planned, but Nordisk would not agree to this: “…because the company greatly values your work.”17 .However, the company did acquiesce and granted Gad’s wish for an early exit, on the condition that he staged another five films before the beginning of June.18 Gad accepted. But a month later, the company changed its mind again. This time, it was the general director Ole Olsen himself who signed the letter:

Upon completion of the last of the plays staged by you we are, after due consideration, willing to release you immediately from your contract as you requested, and as such our mutual obligations will cease..19

What motivated this change of mind is not obvious from the correspondence, but a subsequent letter from Ole Olsen tackles it again.20

Urban Gad must have been an attractive director for Nordisk, considering his monthly salary of 500 kroner. For comparison, we could observe that the company’s chief director August Blom got 666 kroner a month, while E. Schnedler-Sørensen and William Augustinus, who were both permanent appointees in 1911, were paid 300 kroner and 250 kroner respectively for a month’s work. The few men who were directing films in Denmark at that time mostly had a background in acting. At Nordisk, that was true of August Blom, William Augustinus, who was also a “plate photographer”, and Holger Rasmussen, who was fired after a single season. The exception was Schnedler-Sørensen, who had a background as a grocer, travelling salesman, insurance agent and film seller. Apart from those, there were the Aarhus-based Gunnar Helsengreen and Alfred Cohn, who both directed for Fotorama, and Einar Zangenberg, who became chief cinematographer at Kinografen — all former actors. The role of the film director was at that time not a fully professionalised “position”, but Urban Gad was clearly distinctive with his broad palette of previous experience.

A highly competent filmmaker

On the basis of research into this first and hitherto undocumented chapter in Urban Gad’s life, research primarily based on discussions and reviews in newspapers, magazines and journals as well as diverse archives21 ,what seems clear is that Urban Gad entered the film industry in 1910 with an expansive education and very relevant competencies. He brought broad cultural experience with him from his childhood home as well as a high school graduation certificate, had travelled and developed an international perspective on art and culture, had worked creatively as a craftsman and painter, had gained experience in theatre — with writing and staging alike — and could manage creative processes. All of this furnished him with the best possible prerequisites for authoring film manuscripts, directing actors, crafting a film’s visual expression, and organising and leading the production of a film. His debut film The Abyss from September 1910 was a gigantic success and paved the way for an intensive year of work in 1911, when he directed 10 films and wrote the screenplays for 5 of them. During their first year in cinema, Urban Gad and Asta Nielsen commuted between their film commitments in Berlin (Deutsche Bioscope), Aarhus (Fotorama) and Valby (Nordisk Films Kompagni), before the couple settled down in Berlin and made films exclusively in Germany for a number of years.

Notes

1. The context here is a number of telephone calls between Asta Nielsen and her acquaintance Frede Schmidt, which he recorded without her knowledge in the period 1957-1959. They came to light in Torben Skjødt Jensen’s portrait film, Den talende muse (The Talking Muse, 2003). The calls have since featured in the literature on Asta Nielsen, inter alia of the authors Eva Tind and Lotte Thrane. In 2018 DR (Danmarks Radio) a radio series in four episodes on the basis of this material: https://www.dr.dk/radio/p1/asta-og-frede

2. Asta og Frede 1:4 — Fredes bagbutik, timestamp 10:00 https://www.dr.dk/radio/p1/asta-og-frede/asta-og-frede-1-4-fredes-bagbutik

3. Original German: “… einer Arbeitsgemeinschaft, in der Urban Gad eine weit größere Bedeutung für die Filme hatte, als ihm bisher attestiert worden ist.” (Schröder 2010: 210)

4. Gerd is probably referring to the Norwegian actress Gerd Egede-Nissen (1895-1988), who made films at Nordisk films Kompagni in the years 1913-1915. Tage Bull (1881-1960) was a diplomat, a book collector, and an expert on Casanova. Hjalmar Davidsen (1879-1958) was a cinema manager, produced The Abyss in 1910, and served as a director at Nordisk between 1913 and 1917.

5. Other examples of Urban Gad’s “designs” are a tea cosy for the Housekeeping Exhibition of 1902, a doll’s pram for the toys exhibition of 1904, a banner for Dansk Tonekunstnerforening (Danish Sound Artists’ Association) to mark the 100th anniversary of composer J.P.E. Hartmann’s birth in 1905, a decorative wooden board with a motif of the town’s smoking chimneys (photo in Kunst og antikvitetsårbogen 1977), and a Hedebo-style embroidered tablecloth, presented to the Queen in 1909. The pram was crafted by his father, and other artefacts by the ladies of Dansk Kunstflidsforening.

6. Fritz Thaulow (1847-1906) was married to Ingeborg Charlotte Gad (1852-1908), who was a cousin of Peter Nikolaus Urban Gad: see https://www.emmagad.dk/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/halkier-gad-thaulow-20.png. They were married in 1874 and divorced in 1886, and had a daughter, Elise Frölich (1880-1960), who became a prominent actress at Nordisk Films Kompagni in the 1910s.

7. The purpose of Kunstflidsforeningen was inter alia to promote and exhibit Danish craftsmanship, and Emma Gad oversaw many large exhibitions in her period as chairperson. The exhibited artefacts had to be made according to the artist’s original sketches, and to that end, a sketching room was constructed which facilitated collation of designs and was kitted out for the technical work involved, such as scaling up and down, transfers across media, pattern pricking, etc.

8. An exhibition commemorating the Heiberg family, primarily the dramatist, critic and director of the Royal Theatre, Johan Ludvig Heiberg (1791-1860) and his wife Johanne Louise Heiberg (1812-1890), actress and theatre producer. The great influence of the couple on nineteenth-century cultural and intellectual life in Denmark (the golden age) was the motivation for the exhibition, which consisted of artefacts from the family home, reconstructed interiors, for example the sitting room and the office, as well as small dramatic scenes and musical interludes.

9. The play is mentioned as early as the end of September 1908 in newspaper announcements. The rehearsals began only in late May 1909, however, and the play would be the theatre’s first new production of the next season.

10. In the German programme for the film, Urban Gad is credited as director, probably because the German premiere post-dated the premiere of The Abyss, which had already made Urban Gad famous in Germany. The motive must be marketing, pure and simple, which is also Stephan Schröder’s point (2019: 251-252).

11. Nordisk Collection: V,15 fol. 198, posteringsdato 15/6 1910.

12. Both in the scene in Jeweller Hirsch’s shop, where Stella steals a string of pearls and in a scene with Stella and Earl Waldberg (Psilander) in her dressing room, the film cuts in from medium shot to medium close-up and out again in the same scene. In an interior scene at the start of the film, in which Stella and the Earl are walking round a lake, the camera shifts perspective on the walkers.

13. Axel Graatkjær (1885-1969) also goes to Berlin in 1913 with Asta Nielsen and Urban Gad, and establishes a great career in German silent cinema. His last film probably dates from 1929.

14. The story of this contractual drama has been told in several places, including Nielsen 1946: 12 ff, Malmkjær 2000: 91-96, Loiperdinger 2013: 97-99 and Thrane 2019: 93-98. This is why I don’t go into detail here.

15. Nordisk Collection III,18 fol. 42 & 51.

16. Nordisk Collection III,18, fol. 75.

17. Nordisk Collection II,19: Fol. 110 2/3 1912.

18. Nordisk Collection II,19 fol. 293 13/3 1912.

19. Nordisk Collection II,19 fol. 748 12/4 1912.

20. “In reference to your letter of the 17th of this month, the content of which I take note, I assume that the reason why I consent to the dissolution of your contract is not unknown to you. I can only regret that you under these circumstances have been paid your fee without delivering work that reasonably corresponds to it.” Nordisk Collection II,19 fol. 835 18/4 1912.

21. By “archives” I mean both the original documents, primarily in the Nordisk Film Collection at the DFI, but also the archival materials referred to by Bjarne Kildegaard, some of which are held at the Royal Danish Library, and some of which are in private hands.

References

Christensen, Charlotte (1977) ”Omkring år 1900”. In: Kunst og antikvitetsårbogen 1977. Thanning & Appels Forlag.

Engberg, Marguerite (1999) Filmstjernen Asta Nielsen. Aarhus, Klim.

Hald, Tony (ed.) (2003-2019) www.emmagad.dk

Kildegaard, Bjarne (1984/1992) Fru Emma Gad. Tiderne Skifter.

Loiperdinger, Martin (2013) ””Die Duse der Kino-Kunst” Asta Nielsen ’s Berlin Made Brand”. In: Loiperdinger, Martin & Jung, Uli (eds.) Importing Asta Nielsen: The International Film Star in the Making 1910-1914. Herts, John Libbey Publishing Ltd.

Malmkjær, Poul (2000) Asta – Mennesket, myten og filmstjernen – en biografi. P. Haase & Søns Forlag.

Reumert, Poul (1940) Masker og Mennesker. København, Gyldendal.

Schröder, Stephan Michael (2010) “Und Urban Gad? Zur Frage der Autorschaft in den Filmen bis 1914”. In: Unmögliche Liebe: Asta Nielsen, ihr Kino. Wien, Verl. Filmarchiv Austria.

Schröder, Stephan Michael (2019) Literatur als Bellographie – Der Krieg von 1864 in der dänischen Literatur. Berlin, Nordeuropa-Institut der Humboldt-Universität.

Thorsen, Isak (2013) ”Nordisk Films Kompagni and Asta Nielsen”. In: Loiperdinger, Martin & Jung, Uli (eds.) Importing Asta Nielsen: The International Film Star in the Making 1910-1914. Herts, John Libbey Publishing Ltd.

Thrane, Lotte (2019) Maske og menneske. København, Gads Forlag.

Suggested citation

Richter Larsen, Lisbeth (2021): Overlooked, untold and almost forgotten – Urban Gad, film pioneer. Kosmorama (www.kosmorama.org).

Watch the films mentioned on Danish Silent Film: