Introduction

One August day in 1923, on the premises of the Danish film company Palladium, a sturdy desk and upholstered chairs are moved from the offices and outside onto the studio lot. Here, with the studio as backdrop, Palladium managers Svend Nielsen and Lau Lauritzen pose for the press alongside the company's foreign agent Arthur G. Gregory and the German film distributor Lothar Stark. The gentlemen are to sign the company’s first international contract. The newspaper B.T. (11 August 1923) reports that Gregory “(…)will sell Fyrtaarnet and Bivognen in Russia, where the Bolsheviks literally hunger after seeing the two Danes”. The same article describes Lothar Stark as "(...) one of Europe's most powerful filmmakers who, by taking on all of Palladium’s films in much of Europe, has paid the Danish comedies a graceful compliment — and given Palladium a lucrative deal”.

The act of posing for the press was obviously a gimmick, but the signing itself, as well as the press's interest, were genuine enough. Palladium signed a contract with Lothar Stark and Arthur G. Gregory acted as intermediary. As the ink dried on the papers, the company appeared to have the world at its feet.

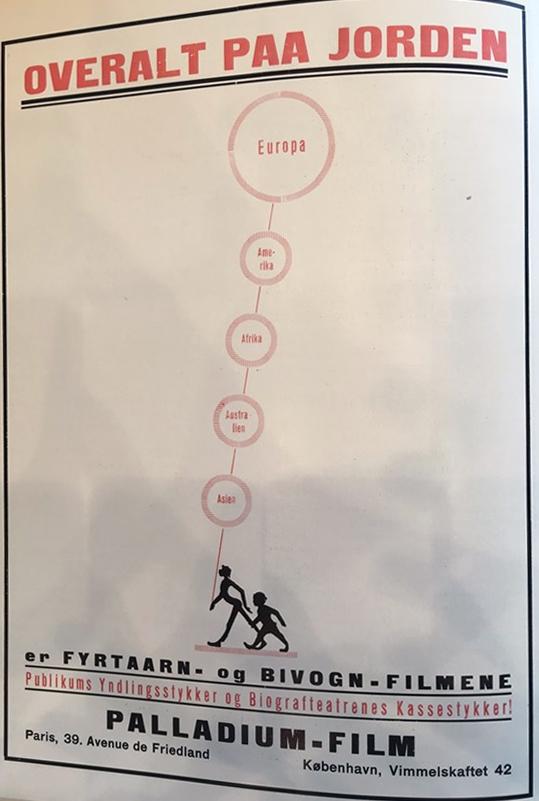

"ALL OVER THE WORLD THE FYRTAARN- AND BIVOGN FILMS are crowd favourites and box office draws!" (Kinobladet, 15 May 1927).

With this expansive claim and a degree of visual pizzazz, a full-page advertisement in the film industry magazine Kinobladet touted Palladium’s products to Danish cinema owners. In the advert's artwork, the company's two stars, Pat and Patachon, appear in silhouette in the inimitable style of Danish graphic artist Sven Brasch, and above them, like high-flying balloons on a string, hover Palladium's world markets: Europe, America, Africa, Australia, and Asia.

The 1923 contract between Palladium, Gregory and Stark thus marked the kick-off of the international success of Pat and Patachon, which, as the advertisement shows, was firmly consolidated by 1927. However, Palladium's "world-renowned film characters" (Engberg 1980), referring to actors Carl Schenstrøm and Harald Madsen’s filmic incarnations, had caught the interest of the Danish audience much earlier, in October 1921, upon the release of Film, Flirt og Forlovelse (Film, Flirt and Fiancées). The film was such a hit that the company modified the film's original premiere poster, the first version of which enticed the viewer with actor Oscar Stribolt in plump profile (again sketched by Sven Brasch), and instead placed the lanky Schenstrøm and the rotund Madsen in energetic silhouette with the sun as an effective, graphic backdrop (Nørrested 1996: 34). The tagline of the poster reads 'Four weeks running ¬'. Crowd-pleasing long runs in Copenhagen’s World Cinema (owned by the Nielsen family) were standard throughout the 1920s. The pattern established in Denmark repeated itself in Scandinavia and then the rest of Europe.

The Palladium films starring Pat and Patachon continued their border-crossing feats throughout the 1920s. Schenstrøm and Madsen became celebrities (particularly in the German market) and Palladium boasted about the pair's continental outreach in its extensive range of promotional material and advertisements. How did Palladium, which was initially established as a Swedish production company in Denmark in 1919, evolve from a Nordic to a transnational success?

This article is primarily based on Palladium's preserved scrapbooks 1 with clippings related to the company and its production. It also draws on the Danish Film Institute's photo archive, relevant correspondence, literature, and Danish and German film trade magazines from the period 1915-1945, as well as relevant research literature. Hauke Lange-Fuch's Pat und Patachon - Eine Dokumentation (1979) contains a wealth of valuable references to coverage of the company's films in German press and is thus both regarded as research literature and primary source.

Recent research has dealt with the characters Pat and Patachon in relation to inter-Scandinavian film culture (Bachmann 2013), but research literature on Palladium — Denmark's most influential production company after Nordisk Films Kompagni during the silent film era – rarely deals with the corporate history of the company. How were the films from Palladium distributed outside of Denmark? What partnerships and deals did financial director Svend Nielsen and artistic director Lau Lauritzen enter into? Which foreign distributors carried Palladium films?

The transnational business relations are crucial factors in the narrative of Palladium's productive 1920s and the more uneven start to the 1930s. Distribution is the "missing link" in researching production and reception, as highlighted by Ivo Blom (Blom 2013: 25) in his mapping of the activities of distributor Jean Desmet and his important role in the early Dutch film industry. By considering Palladium's output through distribution patterns and business relations outside of Denmark, specific micro-histories (Maltby 2011: 13) between Denmark and Germany are revealed. In addition, this work exposes general conditions related to the entertainment industry and the transnational infrastructure of film culture (Blom 2007: 144) in the last decade of the silent era and in the transition to sound.

World Agent Arthur G. Gregory

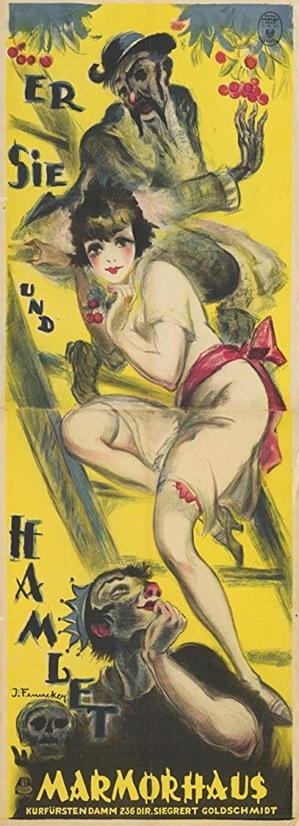

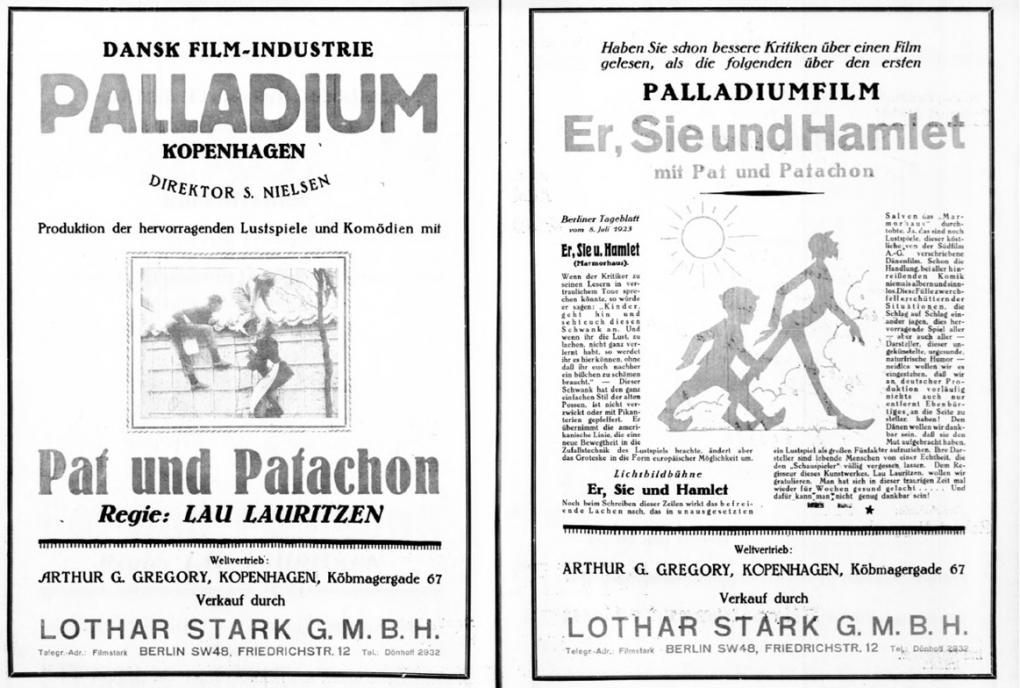

The English-born Arthur George Gregory (21 September 1884 – 10 October 1938), who lived in Copenhagen, first entered into business relations with Palladium in 1923, when the company wanted to expand beyond the borders of the Nordic region. The film was Han, Hun og Hamlet (Lau Lauritzen, DK, 1922), shot in May-July 1922, and premiering in Denmark 16 September of the same year. It was screened for "a large party of people in the film industry from France, Belgium, the Netherlands and Germany" (Ekstrabladet, 15 November 1922) in the first half of November 1922 in Berlin and could finally be shown to the public in the German capital in July 1923. The German audience's first encounter with Pat and Patachon thus took place in the exclusive cinema Marmorhaus in Berlin. Renowned artist Josef Fenneker designed the German poster for Er, Sie und Hamlet.

Palladium obviously pulled out all the stops when introducing Fyrtårnet and Bivognen — already known to the German public as Pat and Patachon (Der Kinematograph, 15 July 1923) — to this new and quite crucial market.

One of Palladium's full-page ads in the Danish trade paper Kinobladet was even dedicated to the German reception of Han, Hun og Hamlet, citing lengthy reviews from Berliner Tagesblatt and Lichtbild-Bühne. At the bottom of the ad, in large print, Arthur G. Gregory is said to handle "World Sales" of the Palladium films. Han, Hun og Hamlet marked the first collaboration between Palladium and Gregory.

What kind of experience did Gregory have in the film industry before Palladium hired him?

He first appears in the context of the Danish film industry on 2 March 1914, where he is linked to the initial registration of a company called Scandinavian Film Agency: “Knud Gjord Scavenius trades as sole proprietor of the Scandinavian Film Agency, Knud Scavenius. Arthur George Gregory is the legal representative for the firm” (Berlingske Tidende, 14 March 1914). The company was located at Kongens Nytorv 8 in Copenhagen. It was registered as a limited company in 1916 with a share capital of DKK 650,000. Among other things, Gregory conducted negotiations with Peter Nansen of Dania Biofilm in 1915 as assistant manager in Scavenius' film sales agency. 2

On 1 February 1918 Gregory's power of procuration was revoked by the Scandinavian Film Agency, however. Why is unknown. After three years at the Scandinavian Film Agency, primarily selling American, but also Italian and English films, Arthur Gregory traveled to America in 1919. He retained his private address at Vodroffs Plads 4, 2nd floor, in Frederiksberg.

Together with the American representative of Nordisk Films Kompagni, Ingvald C. Oes, Gregory set sail from Copenhagen towards America aboard the Frederik VIII on 9 December 1919. The newspaper København refers to them as "two well-known American film men" (København, 10 December 1919), but Gregory was in fact British. Given that his travels were commented upon by the press, he does appear to have made a name for himself after just a few years employed in the Danish film industry. From December 1919 to the spring of 1921 much indicates that Gregory was employed by Fox Film Corporation in the United States. Nadi Tofighian (2017: 166) has pointed out that Gregory also appears to have been working for Nordisk Films Kompagni as a representative in the Chinese market, however.

Employed by Fox Film, Gregory was set to open a Scandinavian sales office in Copenhagen. This was the first step along the way for Fox's plans to extend their operations with branches in Norway, Sweden, and Finland (Wid's Daily, 29 March 1921; Moving Picture World, 9 April 1921). To Kinobladet, Gregory talked about the company's past triumphs, the major films of the upcoming season and even the possibility of Fox shooting in Scandinavia. The article opens by stating that “Mr. Gregory, until recently co-director of Scandinavian Film Agency, has assumed agency of American Fox-Film and opened a Sales Office here in Copenhagen”. This is followed by an entry dryly noting that Scandinavian Film Agency “will be winding up business in an orderly fashion due to difficult conditions on the world market”. Gregory must have counted himself lucky to have signed on with Fox at the right time.

His tenure at Fox did not last long, however. When Ekstrabladet 'met' him on the street in March 1923, Mr. Gregory was already "the former Danish representative of Fox Film". Gregory further elaborated:

The first Danish film I sold overseas was Vor Fælles Ven, which was sold to America on extremely favourable terms. Next, I got hold of Schnedler-Sørensen's Greenland film, and not long ago I got in touch with Dir. Svend Nielsen from "Palladium Film". After negotiating more closely with Director Nielsen, I traveled around Europe with several of Lau Lauritzen's works, including Film, Flirt og Forlovelse, Sol, Sommer og Studiner, Han, Hun og Hamlet and a couple of comedic two-reelers. I’ve managed to sell these films worldwide, and after 1 June there will be very few countries (North America excepted) where our two good friends "Fyrtaarnet" and “Bivognen” will not be known. (Ekstrabladet, 23 March 1923)

The Nordisk Films Kompagni production Vor Fælles Ven (Our Mutual Friend), directed by A.W. Sandberg, premiered in the USA in December 1921. Taking into account both Arthur Gregory's trip to America together with Ingvald C. Oes in December 1919, and his association with Nordisk as a representative in China, it is probable that he served as intermediary to the US market on this production as well. Gregory’s role as representative on Den Store Grønlandsfilm (The Big Film on Greenland) (1922) also ties in with a later collaboration between him and polar explorer Knud Rasmussen in connection with the sale 3 of the film footage of the 5th Thule Expedition 1921-1924, Med Hundeslæde gennem Alaska (By Dog Sled through Alaska), completed in 1927 by director Leo Hansen.

Here, in 1923, Gregory finally emerges as Palladium's representative. He is not mentioned anywhere in relation to the industry screening in Berlin of Han, Hun og Hamlet in November 1922. But when the Palladium production premiered in Berlin's Marmorhaus in July 1923, Arthur G. Gregory was listed as head of world sales. Lothar Stark, producer and distributor with offices at Friedrichstrasse 12 in Berlin, handled distribution.

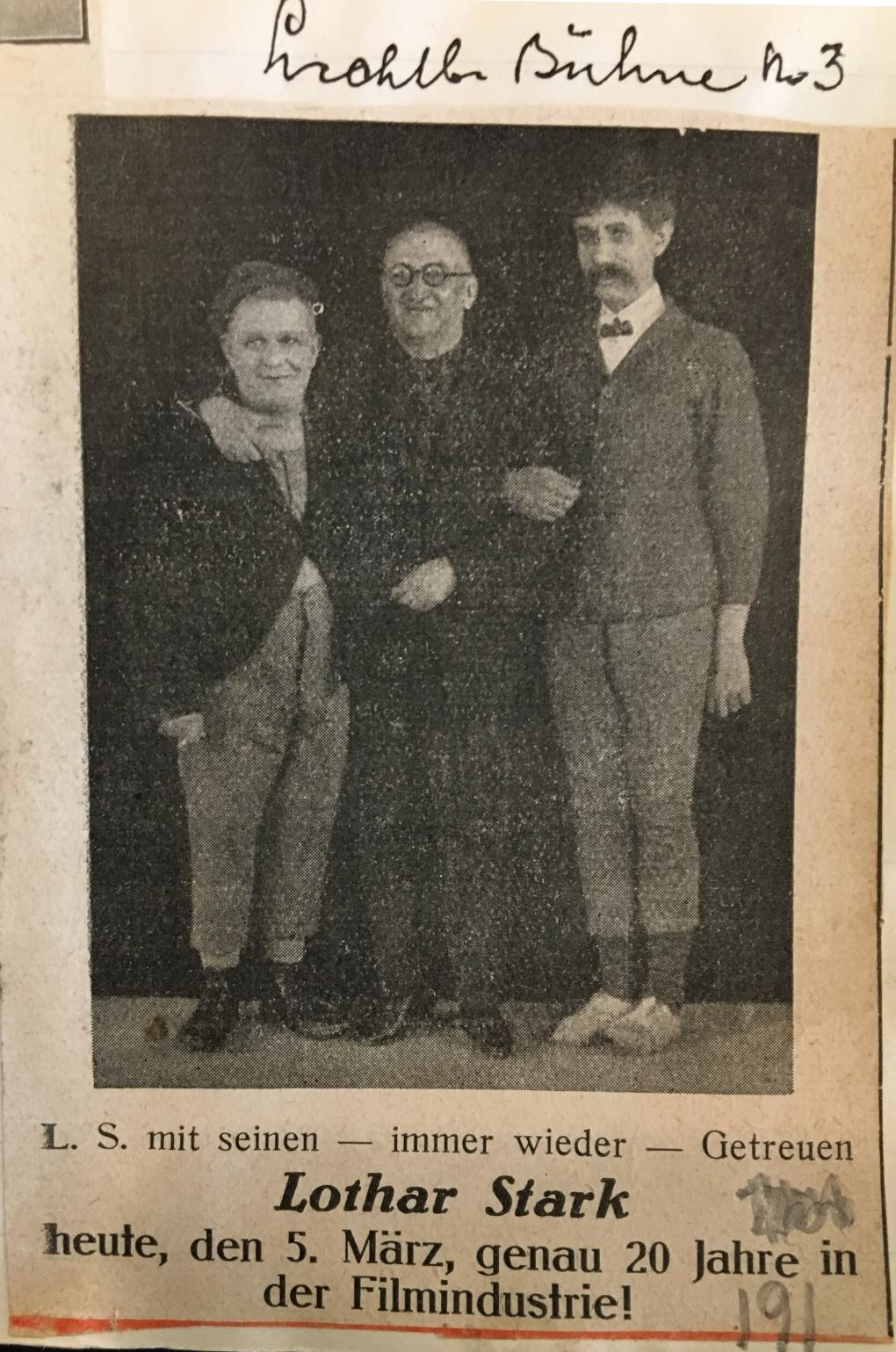

Lothar Stark - "one of Europe's most powerful filmmakers"

By entering into a contract with Lothar Stark and collaborating with Arthur Gregory, Palladium laid a solid foundation for success on the international market. But what enabled Stark to go into partnership with the Danish production company Palladium in the first place?

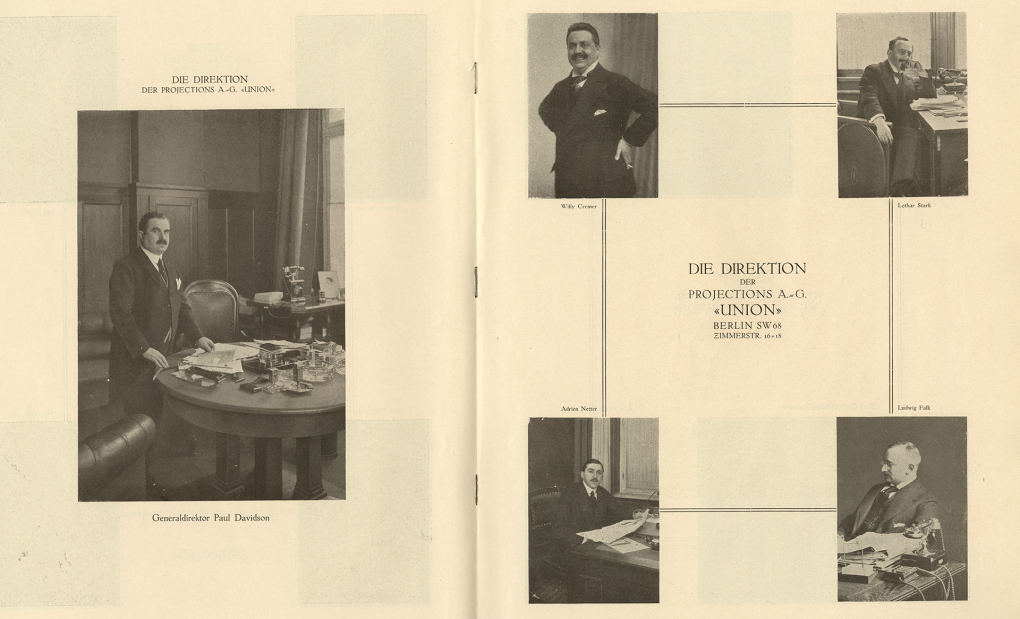

Lothar Stark (5 September 1876 – 31 March 1944), who originally trained as a journalist, is highlighted by several scholars (Claus 2013; Weniger 2011) as a pioneer of the early German film industry. His many connections to Danish film culture from the 1910s until the 1930s is thus illustrative of Danish-German silent film relations and transnational film conditions in general during this period. In Filmen für Hitler – Die Karriere des NS-Starregisseurs Hans Steinhoff (Filming for Hitler – The Career of NS-Star director Hans Steinhoff) Claus characterises Stark thus: “Lothar Stark, who in his time was highly regarded among colleagues for his professionalism and human warmth, is one of the forgotten pioneers of the German film industry” (Claus 2013: 200). Stark’s involvement in Danish-German relations can be traced back to his employment with German PAGU in 1910 (Döge 2016: 49). Paul Davidson's company represented, among others, Asta Nielsen and Urban Gad, and there is good reason to believe that Stark would have been in contact with the two at some point. In a 20-page PAGU promotional insert printed in the German film magazine Lichtbild-Bühne (7 June 1913) Lothar Stark is pictured among the company's management.

At this time, Paul Davidson was the managing director of Der Projektions A.G. "Union". Willy Cremer, Adrien Netter, Ludwig Falk and Stark himself constituted the remaining management. When PAGU moved from Frankfurt to Berlin at the end of 1912, Stark switched to Cines Theater AG in 1913. In the Berlin subsidiary of Italian production company Società Italiana Cines, Stark became one of five investing shareholders with a minor deposit of 1000 marks. In comparison, Italian baron Alberto Fassini contributed 334,000 marks to the enterprise (Der Kinematograph, 24 September 1913).

Stark resigned his job at Cines in November the following year, only to establish a film rental company in his own name. It was located at Friedrichstrasse 43 in Berlin. The boulevard is Berlin's film-industrial hub and up to 100 different companies of varying sizes were based here around 1920 (McGilligan 2013: 52). In late November 1914, the film magazine Lichtbild-Bühne outlined Stark’s situation:

As already announced, Mr. Lothar Stark has left 'Cines' at his own request. He recounts that he has now established his own business in Friedrichstrasse 43. He arranges sales of entire series and major motion pictures to Austria, the Balkans, the Netherlands, Switzerland, Italy, Spain and Scandinavia. Considering his great reputation, we are confident that his firm will run fully satisfactorily.

We wish Mr. Stark the best of luck with the company.” (Lichtbild-Bühne, 28 November 1914)

The short news article is presented here in its full length as it illustrates how highly esteemed Stark already seems to have been by the industry in late 1914. It was, in other words, a well-respected and popular man who faced 1915 as an independent film trader, with offices at the very centre of the Berlin film industry. To start with, Stark was in charge of selling Joe May productions to a wide range of countries. Among those productions, Stark sold the detective film Das Gesetz der Mine (The Law of the Mine) (Joe May, DE, 1915) to Italy, Portugal, South America, and France (Lichtbild-Bühne, 26 June 1915).

Lothar Stark was also involved in the ongoing debate on monopolisation in Germany. During the spring and summer of 1915, the industry was in turmoil, as Nordisk Film's German department Nordische-Film GmbH, led by David Oliver, entered into cooperation with PAGU and Luna-Film-GmbH (Thorsen 2010: 468). The aggressive expansion strategy and the prospect of market dominance of these companies caused a large number of distributors, producers and cinema owners to rally in joint protest. In August 1915, Stark attended such a meeting. Here he delivered the opening statement to about 100 attendees in Berlin's newly built Admiralspalast Theater on Friedrichstrasse, summarising the state of affairs and listing possible consequences. Merely two years after having left PAGU, Stark ranked as a fierce critic of the very same company.

In August 1915, Lothar Stark relocated from Friedrichstrasse 43 to 12. That year his company’s productions included, among others, the drama Das Abenteuer des Van Dola (The Adventures of Van Dola) (Rudolf Del Zopp, DE, 1915), a three-reeler starring Friedrich Zelnik and Norwegian Aud Egede-Nissen. Stark also held the worldwide distribution rights to the film. Furthermore, Stark collaborated with screenwriter and director Richard Oswald on the production of a so-called Richard Oswald Series 1915/16. The first film in a series of eight planned was Und wandern sollst Du ruhelos (And You Shall Wander Restlessly…) (Richard Oswald, DE, 1915), originally released under the title Die schöne Sünderin (The Lovely Sinner). Again, Stark was in charge of world sales.

In addition to Stark's "Film Factory" (Lichtbild-Bühne, 8 January 1916) producing the Oswald series, the company also handled distribution of one-reelers from multiple American companies under Ben Blumenthal. However successful, the Oswald collaboration did not last long. On 12 February 1916, Lichtbild-Bühne reported that the two parties had dissolved business relations in an amicable fashion. At the same time, Lothar Stark's additional portfolio spoke volumes about a bustling business. The 1916 film trade papers in Germany thus listed the following collaborations: Cines-Film, Lloyd-Film, Luna-Film, World Film Corporation, and Eichberg-Film. In addition, Stark was also an avid columnist in Lichtbild-Bühne. For instance, he analysed the sales potential of German films and the general conditions of production in countries such as France, Britain, Spain, and Italy in a lengthy article of 6 July 1918.

In late July 1918, the company was converted into the private limited company Lothar Stark GmbH. The board of directors was composed of Lothar Stark and a Mr. M. Loewenthal (Lichtbild-Bühne, 27 July 1918). Still expanding operations, they distributed films from Astra Filmfabrik in Budapest and Terra-Film GmbH over the next couple of years. Stark joined Terra-Film as a board member, as the company was converted into a private limited company in 1920 (Der Kinematograph, no. 718 1920). In addition, Stark was also involved in the formation of the companies Hella Moja Film-GmbH and Richard Oswald Film-GmbH in the years from 1920 to 1922.

Here, in the years during and after the First World War, Lothar Stark was at the forefront of developments in the film industry. He was by all accounts a jack-of-all-trades: the German trade press referred to him as film merchant, trader, exporter, and skilled film importer. Lichtbild-Bühne (13 July 1918) even described him as an "esteemed colleague" in an introduction to one of his published columns on the industry. A skilled and experienced film merchant, he cropped up everywhere. Marking his crowning achievement, he was elected president of the trade association 'Club der Filmindustrie' (Der Kinematograph, no. 835 1923). It was, in other words, not just anybody that Palladium entered into corporation with in 1923.

"Once again, Danish film has won a place in the sun"

With both Arthur G. Gregory and Lothar Stark on board, Palladium's enthusiasm at landing a major international contract was tangible in the summer of 1923. The newspaper B.T.'s report from the staged contract signing at Palladium struck a bombastic and confident note: "Once again, Danish film has won a place in the Sun" (11 August 1923). Stark choosing to do business with Palladium and not Nordisk Films Kompagni might point to him still holding a grudge against Nordisk on account of their attempt at establishing a monopoly in Germany. Furthermore, it must have rubbed salt into Nordisk's wound that Lau Lauritzen had previously been one of Nordisk’s most popular comedy directors, and was now running the rival company Palladium.

Signing the contract swiftly launched Palladium outside the Nordic region. The studio in Hellerup already produced and released four films featuring Pat and Patachon each year, so Gregory and Stark had their hands full right from the get-go. Following a four-week run of Film, Flirt og Forlovelse (Film, Flirt and Fiancées) (Lau Lauritzen, DK, 1921) in Copenhagen in 1921, the Danish newspaper Berlingske predicted worldwide success: ”Danish humour has a great triumph to celebrate. Strangely enough, the two supporting players have become the leads — making the film a success. Who knows, perhaps Schenstrøm and Madsen will become world-renowned names” (8 November 1921).

As previously stated, Han, Hun og Hamlet (He, She and Hamlet) (Lau Lauritzen, DK, 1922) premiered in Germany at Berlin's prestigious Marmorhaus; a luxurious cinema on a par with Ufa-Palast am Zoo. In Der Kinematograph (no. 856 1923), the "excellent comedies with Pat and Patachon" were promoted in a double-page spread. The ad also cited enthusiastic reviews of Er, Sie und Hamlet from both Berliner Tageblatt and Lichtbild-Bühne. The same applies to a full-page ad in the Danish cinema magazine Kinobladet (1 August 1923), with full quotes from the above-mentioned reviews translated into Danish. Responsible for "World Sales", Arthur G. Gregory was listed at the bottom of the page. To B.T. (10 August 1923) Lau Lauritzen recounted that the film was still drawing crowded houses at the Marmorhaus four weeks into its run, and that the Palladium productions were playing in "20 cinemas all across Germany". In the same interview, Lauritzen also revealed his and Stark’s plan of action regarding the German market:

We have, Lau Lauridsen (sic!) told us yesterday, just had a visit out here by Lothar Starck (sic!), one of Europe's most well-reputed film men. He is the German intermediary at every major foreign deal. You can rest assured that where he buys his films, you are guaranteed success. For this very reason, we are quite proud that he is departing with a contract in his pocket, enabling Ufa to take on our production in Germany, while simultaneously showing the films all across the entire Balkan Peninsula.” (B.T., 10 August 1923)

One week later, Palladium’s Svend Nielsen told the newspaper København (19 August 1923), that Stark had purchased the entire production for most of Central Europe through the company's "local agent" Mr. Gregory. This included Germany and Austria (Nationaltidende, 28 November 1925) as well as Romania, Czechoslovakia, Bulgaria, Yugoslavia and Turkey (Ekstrabladet, 3 January 1924). In November 1923, an agreement with directors Benjamin Mendes and Elias de Hoop of Cinema de Munt (formerly owned by Jean Desmet) in Amsterdam also fell into place. Arthur G. Gregory served as intermediary. Ivo Blom (2003: 428) also singled out De Hoop as the distributor responsible for introducing Pat and Patachon in the Netherlands.

With both Stark and Gregory attached to Palladium as productive agents and overseas distributors, the opportunities for shooting films outside of Denmark were quickly explored. The incentives for shooting abroad may have been to adopt a more international tone and style, thereby catering to a larger audience,

but also to benefit from relations with other production companies and their firmly rooted networks in the film industry. In this connection, Ekstrabladet (3 January 1924) reported on "the German film magnate" Lothar Stark, who, on behalf of the Austrian film company Pan-Film, had requested that "a special Lau-comedy be shot in Vienna and the surrounding area, since the filmgoers in the soft-currency countries would like to see the famous vagabond pair in local settings”. At this point, Palladium had already shot a film partially in Norway, Vore Venners Vinter (Our Friends' winter) (Lau Lauritzen, DK, 1923), but not yet contracted the stars Schenstrøm and Madsen to other companies.

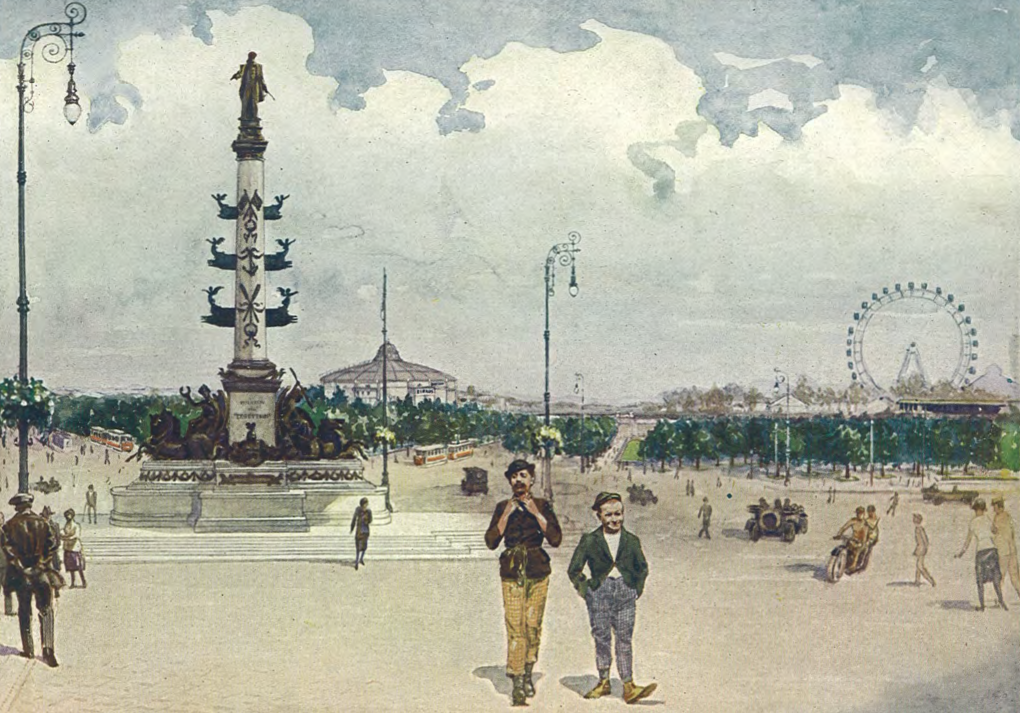

In 1925, however, it was in Sweden that the shooting season started for Carl Schenstrøm and Harald Madsen. For Svensk Filmindustri, Gustaf Molander directed Pat and Patachon in Polis Paulus' påskasmäll (The Smugglers) (SE, 1925). Proceeding to Vienna, Hugo Engel Film produced Zwei Vagabunden im Prater (Two Vagabonds in Vienna) (Hans Otto Löwenstein, AT, 1925). In the run-up to these inaugural foreign productions, agent Arthur Gregory had already been involved with the transnational WESTI consortium. In 1924-25 the consortium attempted to strike a deal with Palladium to produce films with Pat and Patachon in countries outside Denmark (Nørrested 1991: 55 -56). The WESTI film cooperation was established in late 1923 by industrial magnates Vladimir Wengeroff and Hugo Stinnes as a European enterprise against 'Film America' (Higson & Maltby 1999: 60), but had already discontinued operations in the summer of 1925. Gregory was contracted by WESTI as head of the Scandinavian office at the beginning of 1925 (Kinobladet, 15 January 1925, B.T., 2 February 1925). Until 16 September 1925, his letterhead read ‘Arthur G. Gregory, WESTI Consortium’ (Knud Rasmussen collection, A10, box 25, folder 22). As early as 22 August, however, Berlingske reported that WESTI had been wound up "a few days ago."

Lothar Stark and Arthur G. Gregory also collaborated outside the framework of Palladium. In 1924, they ran an ad in the Austrian trade magazine Der Filmbote (24 February 1924), offering productions from Edda-Film, Tumling-Film, Dana-Film, Bewe-Film, Bonnier-Film and Palladium using the slogan “The best films from Scandinavia”. The ad also stated that Stark had offices in both Berlin and Vienna at this point.

Relating to the production and sale of the film shot during polar explorer Knud Rasmussen's 5th Thule expedition, Med Hundeslæde gennem Alaska (By Dog Sled through Alaska) (Leo Hansen, DK, 1927) (Knud Rasmussen collection, A10, box 25, 26) 4, Stark and Gregory corresponded continuously in 1925 and 1926. By agreement with engineer Marius Ib Nyeboe, Knud Rasmussen's business manager, Gregory had managed to secure the rights to sell the film abroad. For Germany, Gregory thus negotiated with Stark about licensing rights starting from November 1925 and running to March 1926. Stark even arranged for a visit from Knud Rasmussen himself in Berlin. Der Kinematograph reported on this visit and detailed the specifics of the agreement between Gregory, Stark and the Rasmussen estate:

“Knud Rasmussen, who has come to Berlin to edit his polar film, we have come to know through Lothar Stark. (…) World sales (North America not included) of his film, entitled Rasmussen's Thule Trip, will be handled by the successful entrepreneur Lothar Stark.” (Der Kinematograph, 21 February 1926)

Here, we see the “successful entrepreneur” Lothar Stark promoting yet another Danish celebrity of the 1920s, polar explorer Knud Rasmussen, in Germany. Pat and Patachon were not the only Danish tricks up Stark’s sleeve, so to speak. Actually, at the turn of the year 1925-26, Palladium and Lothar Stark had ceased partnership in the wake of a quarrel.

Cross-border patents battle

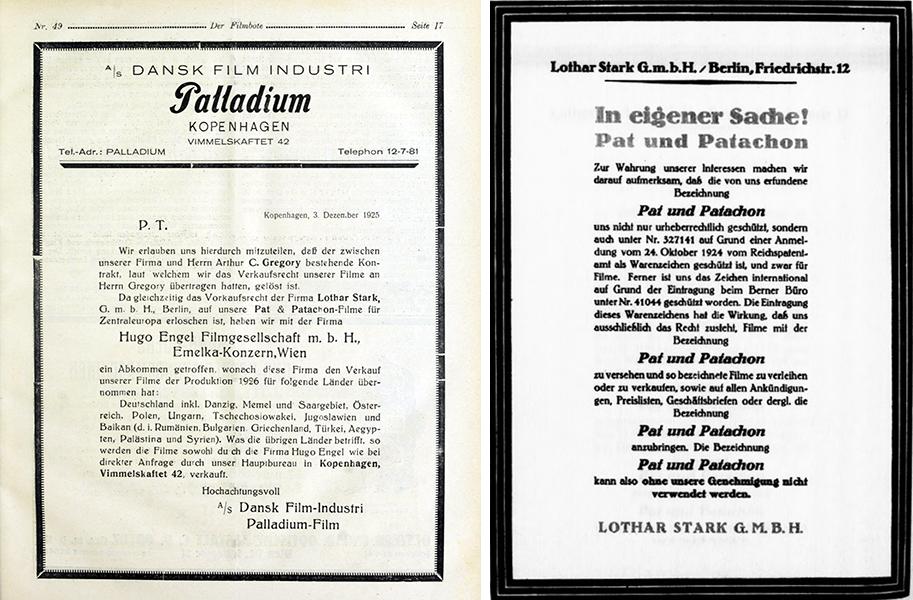

Despite numerous productions and business relations both within and outside the borders of Germany, Lothar Stark and his company were still considered a minor production company (Bock 2009: 350) and thus quite vulnerable to the knock-on effects of losing a major client like Palladium. The fact that Stark in late 1925 indirectly chose to take legal action against the very same company thus seems baffling. The case revolved around the naming rights of 'Pat and Patachon'. Danish newspaper Nationaltidende (28 November 1925) provided the following summary: "The dispute is about the right to use Fyrtaarnet and Bivognen’s German names Pat and Patachon. Mr. Stark considers them his private invention and property.” The sub-heading of the article clearly took sides with Palladium: "Quarrel between Palladium and its former European top agent". The case remained pending until 1927 and the Danish, German and Austrian press covered the story in full.

It is worth looking more closely at the causes and consequences of this isolated case, because the conflict is reflective of the fragmented transnational film industry of the late 1920s, a film culture that was snapping at the heels of the Americans and their ever-tighter iron grip on the industry. As mentioned, the WESTI consortium did not succeed in its European countermeasures and had to relinquish its ambitions in 1925. Given these failures, it is easy to understand the urge among producers, agents and distributors to play it safe. To distribute foreign films in Germany a rather large fee was charged, and Palladium struggled economically on account of this (Nørrested 1991: 56).

Lending out stars Schenstrøm and Madsen and co-producing outside the country thus seemed like a good strategy. Rearranging production led, among other things, to close cooperation with the Austrian producer Hugo Engel in Vienna. Engel produced both Zwei Vagabunden in Prater (Two Vagabonds in Vienna) (Hans Otto Löwenstein, AT, 1925) and Schwiegersöhne (Sons-in-law) (Hans Steinhoff, AT, 1926). In January 1926, the Danish press reported that Hugo Engel (in partnership with the Bavarian company Emelka) had obtained exclusive rights to Palladium's Pat and Patachon-epic Don Quixote (Lau Lauritzen, DK, 1926) even before its completion: “The well-known Viennese filmmaker and financier Hugo Engel has purchased the exclusive rights for all of Central Europe. It has also been sold to Italy and Hungary” (Svendborg Avis, 13 January 1926). Up until this point, Central Europe had been Lothar Stark territory. The sudden shift to Engel and Emelka must have provoked Stark. Possibly, he was provoked to such an extent that it might have been his underlying motive for taking legal action to obtain the patent for the 'Pat and Patachon' names.

About a week after Danish newspapers reported on the patent dispute, Palladium posted a full-page announcement in the Austrian trade paper Der Filmbote (5 December 1925). This stated that Arthur G. Gregory's pre-emptive right to Palladium films had been revoked. So too had Lothar Stark's right to Pat and Patachon productions in Central Europe. For the Emelka group, Hugo Engel-Film in Vienna would take over sales in Germany, Austria, Poland, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia and the entire Balkan region (Romania, Bulgaria, Greece, Turkey, Egypt, Palestine and Syria).

The break had been a long time coming, though. More than a year earlier, on 24 October 1924, Stark had filed a patent application 5 at the National Patent Office in Berlin (Kinematograph, 29 November 1925, Salzburger Volksblatt, 28 January 1926) for the names 'Pat und Patachon'. In a full-page ad targeted at the German film industry, he pointed to this fact (Kinematograph 29 November 1925). To no avail. Only in 1927 was the lawsuit resolved in Vienna, finally ending in a settlement between Stark, Engel and Palladium. At some point in the process, the case files were destroyed by a fire, which might also have caused the parties to accept a settlement (Kinematograph, no. 1074 1927).

Lothar Stark returned to Copenhagen in March 1927. As usual, he stayed at the Palads Hotel (Berlingske, 30 March 1927). Asked by B.T. whether he had buried the hatchet, Stark replied:

“Indeed, I have, and as of today, an agreement has been reached between 'Palladium' and I, resulting in me purchasing the production for the next three years. I have carried the Danish films for three seasons in the past to very pleasing results. With this unpleasant trial over and done with, I have handed over the Pat and Pataschon (sic) naming right to their bearers, the gentlemen Schenstrøm and Miehe-Madsen.” (B.T., 1 April 1927)

Another clear indication that Stark, the Lauritzen family and Palladium were back on good terms by 1927 is provided by an interview of a decade later in the magazine Moderne Ungdom. In the 22 May 1936 issue, Lau Lauritzen Junior (son of Lau Lauritzen) is interviewed, and recounts working for Stark as a young man, nine years earlier. His stint as an apprentice in the accounting department at Lothar Stark's Berlin office can be dated to 1927, as it coincided with the shooting of Der falsche Prinz (The False Prince) (Heinz Paul, DE, 1927) (Pedersen 2010: 44).

In 1928, Stark was back in the pages of the trade papers, advertising the sale of the "entire Palladium production of 1928 with the artists Pat and Patachon" (Das Kino-Journal, 18 August 1928). With the hatchet finally buried, Stark could resume work with his two dear friends just like in the good old days.

The patent action case is symptomatic of the general state of European film culture in late 1920s. It clearly illustrates what was at stake financially for all parties involved. The cracks that are made visible by the wretched affair between Palladium, Stark and Engel point to the general collapse of the possibility of a common film culture. Set against economic self-interest, transnational concerns lost out. Rather than attacking Palladium, Stark was merely defending his own interests as Austrian company Hugo Engel-Film took on distributorship of Pat and Patachon films.

Suicide and escape

For Stark, Schenstrøm and Madsen, it was business as usual yet again. But the film industry, as well as the general political environment, was undergoing dramatic change in the late 1920s and early 1930s. Compared to other European countries, Denmark lagged behind in the introduction of sound film. Thus, Pat and Patachon shot 1000 Worte Deutsch (1000 German words) (Georg Jacoby, DE, 1930), their first talkie, in Germany. Not until 1932, in Palladium's remake of their hit film Han, Hun og Hamlet (He, She and Hamlet) (Lau Lauritzen, DK, 1932), would audiences hear them speak in their native tongue.

In 1926, Arthur G. Gregory set up ‘Extensia’, a company specialising in selling trailers for trucks (Registrerings-Tidende for Vare og Fællesmærker, 5 February 1926). The sudden change in his line of business indicates either tough times in the film industry or complications in the relation to Palladium — possibly both. All the same, Gregory operated both lines of business from the same Copenhagen address, Købmagergade 67, from 1926 to 1929. In June 1927 he signed a contract with Nordisk Films Kompagni for exclusive rights for five years to Maharajaens Yndlingshustru (Oriental love) (A.W. Sandberg, DK, 1926) in China. He paid $300 in license fees (NFS: XII, 46: 66).

Subsequently, in the early 1930s, Gregory tried to establish a new film company in collaboration with Triangel Film in Stockholm (B.T., 14 April 1932). At almost the same time he was negotiating on behalf of German film producer Christophe Mülleneisen Jr. of Cinema-Film in Berlin, regarding “… The sale of German films here in the country and the possibility of shooting Danish films financially supported by Germany” (Dagens Nyheder, 26 June 1932). In 1935, he once again collaborated with Lothar Stark, who was living in exile in Denmark (Variety, 20 June 1933) following the Nazi takeover in 1933. Concurrently, any mentions of Stark, a Jew, in the columns of the German film trade press vanish into thin air. In Denmark, the two former Palladium associates — Stark and Gregory — built on the past success of Pat and Patachon, signing a contract with Palladium. In 1935, Danish newspaper B.T. (18 January 1935) wrote:

The plans of managers Lothar Starck (sic!) and Gregory to shoot a new Pat and Patachon-film are now so far along that Messrs. have entered into contract with the two popular wags. At the moment they are searching for a director.

The director they were negotiating with was the seasoned Holger-Madsen, but once again, the plans fell flat. Instead, Schenstrøm and Madsen went on to shoot in Germany with Majestic Film, where Fred Sauer directed them in both Mädchenräuber (Girl Kidnappers) (DE, 1935/1936) and Blinde Passagiere (Stowaways) (DE, 1936). Strikingly, on the very same page as this article in B.T. (18 January 1935), another piece was printed under the headline "German Film Victory". The opening line reads: "You’ve gotta hand it to the Nazis that they are working to show that they can manage without the Jews, and the last film they produced is simply wonderful.” Even if it is just the innocuous love story Regine (Erich Waschneck, DE, 1935) that is referred to here as wonderful, this juxtaposition on the page is a shocking reminder of B.T.'s editorial priorities at the time — not least in the light of Stark’s position as a Jew watching his years of work in the German film industry laid to waste.

Following his almost endless series of attempts to gain foothold in the film industry, Arthur G. Gregory eventually gave up. Tragically, he chose suicide by "veronal poisoning" (Berlingske, 11 October 1938) — i.e. an overdose of strong sleeping pills — as a last resort and died at the age of 54 on 10 October 1938. Three months earlier, Palladium director and manager Lau Lauritzen had passed away at the age of 60.

Lothar Stark remained in exile in Denmark until 1943 (Pedersen & Clement 2018: 559), when he and his wife Else fled across the Öresund to Helsingborg in Sweden.

After several exhausting days on the run, they arrived in Sweden early in the morning on 3 October 1943. In a letter 6 to their sons Rolf and Werner, Stark described the highly dramatic events in detail. From Helsingør, they traveled via Malmö to Stockholm, where Stark eventually wrote the letter. Here, aided by an acquaintance from the Transit-Film company, the Stark family settled and Lothar Stark tried to resume his business almost as soon as he arrived. With a few thousand Danish kroner in his pocket and no luggage — besides the layers of clothing that Lothar and Else traveled in — it was by no means an easy 'new start'. Lothar Stark died before the end of the war, on 31 March 1944 in Stockholm.

Conclusion

Both Arthur G. Gregory and Lothar Stark left noticeable marks on Palladium’s successful ‘20s. Svend Nielsen and Lau Lauritzen alike repeatedly emphasised the importance of the two agents. The Danish press regularly wrote about Palladium's dealings with "the well-known Filmmaker", "World Agent", "one of Europe's mighty Filmmakers" and other terms of utmost praise. Stark even called himself "the international adoptive father of the wonderful boys Pat and Patachon" (B.T., 8 December 1932), while Fyens Stiftstidende (16 July) in 1933 concluded: "General manager Stark is one of the best known personalities in Danish film.”

Examining both historical developments and interrelationships between Gregory and Stark — Palladium's general agent and principal distributor — allows us to identify the factors and motives that 'created' Palladium's international success. Palladium's highly marketable product — serial films with popular characters in the lead roles — was a good, international product from the get-go. Linked with Gregory's proactive agency and Stark’s insider’s perspective on the German market in particular, a solid business model was created. As described, distributors were replaced and exclusive right holders returned to favour along the way. Star players were on loan to foreign companies and co-productions were a necessity. A faltering industry, adjusting to the coming of sound, played it safe. The patent lawsuit in Austria, whereby Stark tried to prove his inventor’s right regarding the ‘Pat’ and ‘Patachon’ names, was equally about lost market shares and self-interest, given that the production and distribution company Hugo Engel-Film had more or less taken over Lothar Stark's position in relation to Palladium at that time.

During the 1920s and early 1930s, many film companies struggled and even succumbed to both political and industrial U-turns. Nordisk Films Kompagni was one of them (Thorsen 2017). By focusing on business relations, distribution, legal proceedings and mutual interests, Palladium’s successful business strategy is exposed.

The staged contract signing in the studio lot of Palladium;, Gregory's initial work in the film industry prior to the collaboration with Palladium; Stark's esteemed position in Germany until 1933; the circumstances under which Gregory and Stark crossed paths outside Palladium's sphere. Together, all these fragments outline the history of an adaptable and resourceful film company, one in which the relations with both agents and distributors prove crucial. To state that Lothar Stark and Arthur G. Gregory were the main reasons for Palladium surviving the coming of sound is perhaps an exaggeration. But in the telling of the transnational success of the company, they are both of decisive importance.

Notes

1. The Palladium collection at the Danish Film Institute primarily contains scrapbooks of press clippings on each of the company's film titles as well as actors and the Palladium cinema. However, some of the company's documents from the silent era are also preserved in the collection. This includes a list of distributors and the contracts of Carl Schenstrøm and Harald Madsen.

2. Letter from Arthur G. Gregory to Peter Nansen 15 February 1915. NKS 4043, 4°. The Royal Danish Library, The Manuscript Collection.

3. Letters between Arthur G. Gregory and Ib Nyeboe. Knud Rasmussen’s Archive. A10, Box 25, Folder 1-33. Box 26, Folder 17-40.

4. See: Lund, Jørgen-Richard: ”Nazismens iskolde spor” in the periodical Grønland, no. 6, October 1996 and Jørgensen, Anders: ”Primitiv film? Knud Rasmussens ekspeditionsfilm” in Kosmorama, no. 232, Winter 2003 for further information on Knud Rasmussen and film productions related to him.

5. Lothar Stark states patent no. 327141 as the applied at Reichspatentamt and no. 410444 at Berner Büro (Kinematograph, 29 November 1925). In the Danish News Paper Vestkysten (21 April 1927) trademark no. 96.408 in the Austrian patent office is stated.

6. Letter dated 10 October 1943: http://www.his2rie.dk/kildetekster/holocaust/tekst-61/

Literature

Bachmann, Anne (2013): Locating Inter-Scandinavian Silent Film Culture. Stockholm: Stockholm University Library.

Blom, Ivo (2003): Jean Desmet and the Early Dutch Film Trade. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Blom, Ivo (2007): ‘Infrastructure, open system and the take-off phase. Jean Desmet as a case for early distribution in the Netherlands’. I: Networks of Entertainment: Early Film Distribution 1895-1915. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Bock, Hans Michael (2009): The Concise Cinegraph: Encyclopaedia of German Cinema. New York: Berghahn Books.

Claus, Horst (2013): Filmen für Hitler. Die Karriere des NS-Starregisseurs Hans Steinhoff. Wien: Verlag Filmarchiv Austria

Higson, Andrew & Maltby, Richard (ed.) (1999): “Film Europe" and "Film America": Cinema, Commerce and Cultural Exchange 1920-1939. Exeter: University of Exeter Press.

Pedersen, Paw Kåre (2010): Unge Lau: Historien om Filmmanden Lau Lauritzen Junior og ASA Film: 1. Del 1910-1945. København: Books on Demand.

Pedersen, Paw Kåre, & Clement, Niels Jørgen (2018). Historien om Saga Studio: Saga Film A/S. S.l.: Mellemgaard.

Lange-Fuchs, Hauke (2014): ‘Pat and Patachon: A 'German' comedy couple on the screen’. I: Journal of Scandinavian Cinema, Volume 4, Nr 3.

Maltby, R., Biltereyst, D., & Meers, P. (Eds.). (2011). Explorations in new cinema history: approaches and case studies. Chichester, UK: Wiley-Blackwell.

McGilligan, Patrick (2013): Fritz Lang: The Nature of the Beast. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Nørrested, Carl (1991): ’Over de nordiske græser’. I: Kosmorama nr. 198.

Nørrested, Carl (1996): ‘Fy og Bi’. I: Kosmorama nr. 215.

Thorsen, Isak (2010): ‘Nordisk Films Kompagni Will Now Become the Biggest in the World’. I: Film History, Volume 22, Nr 4.

Thorsen, Isak (2017): Nordisk Films Kompagni 1906-1924: The Rise and Fall of the Polar Bear. East Barnet: John Libbey Publishing. KINtop Studies in Early Cinema, Bind. 5.

Tofighian, Nadi (2017) ‘Distributing Scandinavia: Nordisk Film in Asia’ I Early Cinema in Asia (Nick Deocampo (ed)), Indiana University Press.

Weniger, Kay (2011): „Es wird im Leben dir mehr genommen als gegeben…“ Lexikon der aus Deutschland und Österreich emigrierten Filmschaffenden 1933 bis 1945. Eine Gesamtübersicht. Hamburg: Acabus Verlag.

Suggested citation

Astrup, Jannie Dahl (2020), World Agents and Mighty Filmmakers – The Transnational Business Relations of Palladium. Kosmorama #276 (www.kosmorama.org).

Watch the films mentioned at 'Stumfilm.dk':