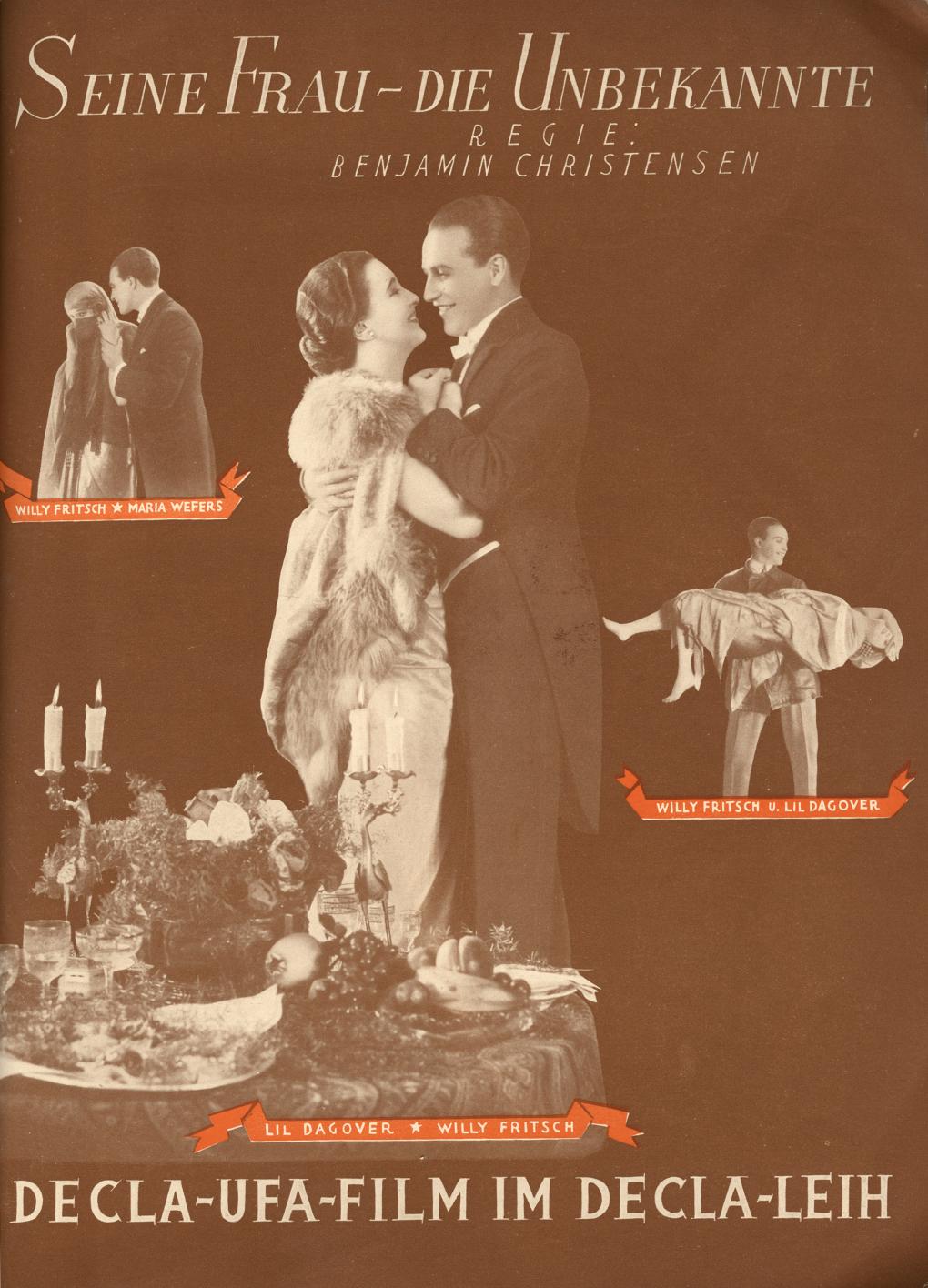

The research project A Common Film Culture? consists of a number of sub-projects, many of which are in whole or in part focused on particular historical individuals. They explore (or at least leave room for) practitioner’s agency, a concept that has proven itself useful in research on contemporary Danish and Nordic cinema (Hjort, Jørholt & Redvall 2010; Hjort & Lindqvist 2016). This article, primarily methodological in intent, aims to explore the usefulness of the concept for the writing of film history, in part by comparing it with the closely related rational-agent model of creativity (Bordwell 2008). To serve as an illustration, the article will discuss a German film, an UFA/Decla-Bioscop production from 1923: Seine Frau, die Unbekannte (His Unknown Wife), written and directed by the Danish filmmaker Benjamin Christensen and shot by the Danish cinematographer Frederik Fuglsang.

The film survives, but it is little known today and rarely shown. In 1923, however, it was considered one of its production company’s top releases. The trade weekly Lichtbild-Bühne published a long article in early September previewing the major releases of the upcoming season. For Decla-Bioscop, the biggest was clearly the superproduction Die Nibelungen (Fritz Lang, DE 1924), but right behind it we find Benjamin Christensen’s film: “In second place on the list of Decla films appear the fairy tale film directed by Dr. [Ludwig] Berger, Der verlorene Schuh, and the film Wilbur Crawfords wundersames Abenteuer directed by Christensen” (Anon. 1923b: 8). Wilbur Crawford’s Wonderful Adventure was the film’s working title, used until shortly before the film’s premiere on 19 October 1923.

While I obviously hope to draw attention to what I think is an unjustly overlooked film, you do not need to have seen the film to follow the argument I will be making, which is primarily a methodological one. I hope to show what we can learn from a limited and unpromising set of sources, particular a brief interview with Christensen published while the film was in production (Anon. 1923a).

“An exceedingly interesting experiment”

As film historians, we work with both the films themselves and other kinds of source material to better understand how and why the films were made. When we read written sources like press reports and reviews, we find that they include implicit assumptions about films and filmmaking, which may or may not correspond to our own. One example is the review of Seine Frau, die Unbekannte published in the trade journal Der Kinematograph ten days after the film was released in Germany on 19 October 1923:

An interesting movie by Benjamin Christensen, who shows himself from a completely different side again in this picture. For the average cinemagoer perhaps no more and no less than an interesting movie in itself; for the professional [Fachmann], however, an exceedingly interesting experiment, particularly from the perspective of the German film producer. (Der Kinematograph vol.17:871, 28 October 1923: 8)

Once we get past the infelicity of the word “interesting” being repeated three times in two sentences, we may note that the reviewer clearly regards this movie as a director’s film: Benjamin Christensen’s name is mentioned at the outset, the new film is described as an “experiment,” and Christensen’s films are said to show sides of “himself” – a conception fairly similar to what would later be called auteurism.

The reviewer also compliments Fuglsang on his “irreproachable” cinematography and writes quite a bit about the leading actors, Lil Dagover and Willy Fritsch. Fritsch was an unknown newcomer then, but became one of the most popular German stars of the 1930s; the reviewer very presciently calls him “one of the few people in films who has the prospect of moving into the top rank [in die große Klasse],” a remark Fritsch would later quote in his autobiography (Fritsch 1963: 15). The main readers of Der Kinematograph were film and cinema professionals; Fritsch describes the publication as an “always restrainedly objective [sachlich-zurückhaltende] professional journal” (Fritsch 1963: 15). The reviewer, addressing an audience of professionals, of Fachmänner, clearly assumed that this audience would regard as reasonable and proper the crediting of Christensen as the film’s maker, and that the audience would know who he was.

The trade weekly Lichtbild-Bühne also acknowledged Christensen’s fame, even if it was not quite aware of which Scandinavian country he came from. It announced in mid-May that Seine Frau, die Unbekannte had gone into production:

The Swede [!] Benjamin Christensen, who has made a name for himself in the international film world through his films Det hemmelighedsfulde X, Hævnens Nat, and Häxan, has written the screenplay for this film. The direction will also be in his hands. (Lichtbild-Bühne v16:20, 19 May 1923: 37)

Even though Häxan (Witchcraft through the Ages, SWE 1922) would not be released in Germany until May 1924, readers were evidently assumed to be familiar with both that and Christensen’s earlier films, Det hemmelighedsfulde X (Sealed Orders, DK 1914) and Hævnens Nat (Blind Justice, DK 1916).

Häxan, Christensen’s newest and most radically experimental film, was shown in a closed screening to German film professionals on 15 October 1923 (Monty 1999: 46), and there may have been other screenings earlier; in an interview from July, Christensen says, “In Berlin I think it [Häxan] has been shown a dozen times for a select circle of writers and others” (Anon. 1923a). We may speculate that the Kinematograph reviewer and at least some of his readers were well aware of Häxan and its unusual character. It had been a radical experiment, a fictional documentary about witchcraft beliefs and persecutions in late medieval and early modern Europe, largely staged, but only partly narratively structured. With its elaborate sets and costumes and its groundbreaking special effects, it had been years in the making and ended up costing a huge sum of money. By comparison, Seine Frau, die Unbekannte appears a far more modest and conventional undertaking. It is therefore highly intriguing that the review calls it an “experiment”; but, frustratingly, the review does not elaborate. We would like to know why the film would be “exceedingly interesting” to the “Fachmann”, but the reviewer does not tell us. Later in this article, I shall hazard a guess.

On a broader level, the framing of Christensen as a doer, an agent, a filmmaker whose works are valuable creative experiments, evidently has a great deal in common with an approach to film history that regards the agency of filmmakers as a central concern. The central figure in the development of such an approach in a methodologically self-conscious fashion has undoubtedly been David Bordwell. He proposed such a model in his 1988 Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema, an important book whose focus on a particular director’s oeuvre has perhaps meant that its methodological significance has been not been as widely appreciated as it should have been. Bordwell argues that in order to explain Ozu’s art, the best approach would be to regard him as a rational agent operating within a set of constraints imposed by industrial norms, technological resources, and social contexts: “The language of rational action – strategies, tactics, choice, selection, decision, problem, solution – has permeated my account of Ozu’s art. That is because a conception of the filmmaker and the film viewer as deliberating agents is central to the historical poetics I propose” (Bordwell 1988: 162). In the key methodological article “Poetics of Cinema” from 2008, Bordwell restates this conception of the filmmaker as a rational agent:

Filmmakers work with tools and materials, operating within institutions that offer both constraints and opportunities. These factors can be summed up under the rubric of practices. How shall we understand these practices? Two ideas can guide us. First, there is a rational agent model of creativity. This follows from the idea that the filmmaker selects among constructional options or creates new choices. Our task becomes that of reconstructing, on the basis of whatever historical data one can find, the creative situation that the filmmaker confronts. The rationality at stake is largely one of means‑end reasoning. Assuming a certain end in view, certain options are more likely to fulfill it than others. […] A second, institutional dimension of practice forms the horizon of what is permitted and encouraged at particular moments. (Bordwell 2008: 28)

In my own work, I have found this conception tremendously valuable (see Tybjerg 2005, 2016). Even scholars highly sympathetic to Bordwell’s work, however, have tended to avoid explicitly adopting the rational agent model.

A seemingly closely related concept is that of practitioner’s agency, developed by Mette Hjort. It involves “trying to get a clear sense of what relevant film practitioners were trying to achieve with a given film, of the nature of the various deliberative processes that governed the work of filmmaking, and of the specific solutions that particular individuals devised in response to challenges encountered along the way” (Hjort 2010: 117). Like Bordwell, Hjort uses a language of intentions, plans, deliberations, choices, decisions, and solutions, and she treats practitioners as having rational agency to (at least) the same extent as he does. Nevertheless, she has chosen a different concept label from that promoted by Bordwell. For film historians, this raises the question: which of these labels should we prefer – practitioner’s agency or the rational agent model? What are the relevant differences between them? What are their drawbacks?

Rational Choice and the Irresistible Smile

I think that an important reason why Bordwell’s model has been disfavored lies in the word “rational.” Bordwell based his model on the 1980s work of social theorist Jon Elster, who from a basis in Marxism strongly advocated the adoption of rational choice theory from economics to other fields of social research including politics, social history, and the study of artistic creativity. In endorsing and adopting Elster’s creativity model, Bordwell thus used “rational” in a specific technical-theoretical sense. At the same time, the term presented a clear, polemical contrast to film theories focused almost exclusively on unconscious, irrational forces: in the programmatic article “A Case for Cognitivism,” which appeared around the same time as the Ozu book, Bordwell advocated the adoption of the rational-agent model as part of a larger effort to offer an alternative to a film-theoretical paradigm overly beholden to Lacanian psychoanalysis and Althusserian subject-position theory (Bordwell 1989a: 31-32).

While cognitive film theory has become an established approach, film scholars have nevertheless remained chary of rational choice theory. Some see the theory as tied to the abstract figure of homo oeconomicus, the assumption that the agent is “rational, omniscient, egoistic, and endowed with unbounded cognitive powers” (Donnelly 2018: 99; citing Chang 2014). Bordwell has been said to promote such “neoliberal” notions (Shaviro 2008: 51), but that is obviously a caricature, failing to consider Bordwell’s explicit appeal to Marxist theorists in his account of the model. Moreover, from the start, Bordwell took into account the developing critique of rational choice theory for having an unrealistic view of human psychology: in his 1989 article, he cites the work of Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky, clearly accepting that human rationality is often imperfect and rules-of-thumb-based.

As I mentioned above, Bordwell derives his rational-agent model from the work of Jon Elster. Since the 1980s, however, Elster has revised his ideas, arguing (under the influence of Kahneman, Tversky, and others) that rational choice has less explanatory power than he believed earlier: “Today, I believe that the idea of choice is at the core of social science explanations, but that rational choice is only one variety among others” (Elster 2018: 202; original emphasis). The idea of choice also remains at the center of Elster’s more recent discussions of creativity:

The fact that authors often make many drafts before they are satisfied, or before they lay down their pen, is evidence that they are engaged in a process of choice and that they possess – but may not be able to state – criteria for betterness. Often these drafts involve small variations, suggesting that the authors are aiming at a local maximum of whatever form of betterness they are striving for. (Elster 2009: 11; original emphasis)

Yet authors, filmmakers, and other artists may have countless different options to choose from, and may invent new ones as well. This means that the range of choices must be narrowed on the basis of instinct or other non-rational grounds: “Although a ‘rational creator’ may try to make the problem more tractable by deliberately excluding some [word] sequences, too many will usually remain for choice to be a feasible selection mechanism. Instead, the author will have to rely on his or her unconscious associative machinery” (Elster 2009: 11-12).

So, while decisions about particulars and details may be based on rational choices, higher-level decisions about the artwork as a whole may not be, Elster suggests. He pursues this idea using a variety of metaphors (including one that he admits in a footnote is factually misleading, that of the brain being divided into two halves, a logically calculating left brain and an intuitively creative right brain):

Rational creation is therefore largely about getting the second decimal right or, to shift the metaphor, about climbing to the top of the nearest hill. In yet a further metaphor, this is a left-hemisphere task. The right-hemisphere task of getting the first decimal right, or finding a hill that towers over the others, is not within the scope of rationality. Yet even reduced to the task of fine-tuning, authorial rationality matters. It may be better to find the top of a small hill (a ‘minor masterpiece’) than to remain on the slopes of a larger one (a ‘flawed masterpiece’). (Elster 2009: 12)

For an example of this – a decision to climb an entirely different hill, as it were – we can look at an interesting anecdote about the making of Seine Frau, die Unbekannte.

In her autobiography, Ich war die Dame, the film’s leading lady Lil Dagover claims that the casting of Willy Fritsch caused the film’s story to be drastically changed. The completed film has a rather convoluted plot, but it is worth summarizing in some detail in order to better understand the change Dagover describes. Seine Frau, die Unbekannte begins by introducing us to a young painter, Wilbur Crawford (Fritsch), who has lost his eyesight in the war. He tells his mother of a romantic adventure he experienced before the war, which is presented as a flashback. At a masquerade ball, Wilbur was approached by a young woman dressed in an oriental fantasy costume, a long veil covering her face. She was afraid, and Wilbur offered her shelter. The next morning, she disappeared. Wilbur’s mother resolves to track down the mystery woman who left such a deep impression on her son. She is aided by Eva, a war widow (Dagover) who works for the Red Cross, offering help to invalid soldiers. They succeed in identifying the woman, but she turns out to have a police record. Nevertheless, they contact her, and she reluctantly agrees to meet with Wilbur. On the night of the meeting, however, she changes her mind, despite Eva’s entreaties. Eva goes to deliver the bad news to Wilbur’s mother, but Wilbur, hearing her voice, mistakes her for the mystery woman. Not wanting to disappoint him, Eva pretends to be her. Eva and Wilbur soon grow fond of each other. One day, however, the mystery woman suddenly turns up, exposing the deception, but overhearing her argue with Eva, Wilbur realizes that the mystery woman is calculating and selfish. He marries Eva, and they have a child.

Wilbur now goes to America and receives a miraculous operation restoring his eyesight. At this point, the film’s tone changes from somber and melodramatic to comedic and light-hearted. When Wilbur fails to recognize Eva when stepping off the steamer from America, she rushes off. Before Wilbur can see her face, she moves out of the house, taking the baby with her. Wilbur manages to find out where she has gone, but she locks herself in the bathroom so he can’t see her. Wilbur then takes the baby with him to force her to come to him. In the world of this film, a man obviously cannot take care of an infant by himself, so he gets his mother to hire a nanny. The mother arranges for Eva to get the job under the false name of Mrs. Scott. Eva sets about seducing her husband: she wants him to fall for the attractive Mrs. Scott rather than stay faithful to his wife. Initially, he barely notices her, but when she models for him in the nude, she not only inspires him to paint again, she also awakens his romantic interest. Having succeeded in getting him to prefer Mrs. Scott to his wife, she reveals that both women are actually her, and all ends happily.

In her memoir, Dagover claims that the comedic part of the movie following the successful restoration of the hero’s sight was not in the original script at all. She writes that it was “a deathly serious film [einen todernsten Film]” (Dagover 1979: 149), where the hero only regained his sight at the end. When doing screen tests of some young actors for the main role, however, Christensen was so impressed with Willy Fritsch’s hearty, spontaneous laughter that he not only hired him but reshaped the movie to fit Fritsch, “the man with the irresistible smile,” and his jaunty persona: “The tragedy became a comedy” (Dagover 1979: 150).

Many show-business memoirs contain such anecdotes of important, large-scale creative decisions being improvised at the spur of the moment, but one may often suspect writers of exaggerating in the interest of a good, colorful story. Dagover’s recollection (written more than fifty-five years after the fact) is indeed somewhat imprecise; she writes that in the revised storyline, “Willy” regains his sight “already at the outset” (Dagover 1979: 150). In the film as we have it, however, the operation happens two-fifths of the way in; the comedic part comprises the remaining three-fifths. At the time, Christensen himself said of casting Fritsch: “I have chosen him because I wanted a fresh young man with the right look” (Anon. 1923a), which does not really sound like a game-changing improvisation. Even so, let us allow for the sake of argument that the casting of Fritsch caused Christensen to rewrite his film, giving its second part a comedic tone it did not have in the original screenplay.

If this is the case, it would mean that the director drastically reconceived the work not long before the start of production on the strength of an unknown newcomer’s smile. This seems like a very risky move – it would be much less disruptive to replace Fritsch with a less cheerful performer. It certainly seems very hard to say that it is a rational choice – there is no way that Christensen could have enough information to fully weigh the alternatives. He would have had to rely on instinct. Even if Dagover’s anecdote is embellished, I think it provides a good illustration of why a rational-agent model may not fully capture the processes of artistic decision-making.

Asking Questions about Past Intentions

Turning to the alternative concept of practitioner’s agency, it should be evident that it is equally committed to describe in rational-agent terms what Elster calls the pursuit of “betterness” through revision and deliberate choice (Elster 2009: 11). We find a clear presentation of the concept in the introduction to The Danish Directors 2, a book of interviews with contemporary filmmakers by Mette Hjort, Eva Jørholt and Eva Novrup Redvall:

To embrace the concept of practitioner’s agency is to acknowledge that films are made by persons, or, as philosophers put it, by agents. Films, that is, are the result, to a very considerable extent, although not exclusively (chance and institutional circumstances being an inevitable factor) of agents’ articulation of plans and sub-plans, and of their deliberations and decision-making with reference to such plans. (Hjort, Jørholt & Redvall 2010: 14)

There is even an explicit acknowledgment of the rationality of the agent, even if it has had the qualifier “subjective” added to it: “By foregrounding the idea of filmmaking as an activity undertaken by agents, we give explanatory priority to the self-understandings, to the subjective rationality, of those who are involved in the making of films” (Hjort, Jørholt & Redvall 2010: 14-15). In other words: we should give particular consideration to how filmmakers and film workers describe and explain their own practice.

The concept was developed by Mette Hjort, who used it in two earlier books, both of them contributions to series of short monographs on particular films – one on Center Stage (Ruan Lingyu, aka Actress, HK 1992), Stanley Kwan’s film about the great Chinese silent film star Ruan Lingyu, the other on Italiensk for begyndere (Italian for Beginners, DK 2000), Lone Scherfig’s Dogma comedy (Hjort 2006; 2010). The concept is also given a position of importance in the Companion to Nordic Cinema Hjort has co-edited with Ursula Lindqvist: “A clear commitment when designing the Companion was to foreground practitioner’s agency,” they write in their editors’ introduction, stating their belief that through “this emphasis on practitioner’s agency, the Companion offers a model of scholarship relevant not only to Nordic cinema but to Film Studies generally” (Hjort & Lindqvist 2016: 8).

To justify doing research interviews with filmmakers is an important practical purpose of the concept: “To take seriously practioner’s agency is to believe that it is important to ask questions about the intentions of the makers of films, and to seek answers to such questions through in-depth, research-oriented interviews, among other things” (Hjort 2010: 117). It is when filmmakers are willing to give researchers time to conduct detailed interviews with them (which is much more likely to happen, Hjort argues, in smaller filmmaking nations) that “the details of what I want to call practitioner’s agency can be accessed to a significant degree” (Hjort 2006: 6). Thus, all the articles in the section of The Companion to Nordic Cinema entitled “The Eye of Industry: Practitioner’s Agency” are based on interviews. These articles all deal with recent or contemporary cinema, however; what are silent film historians going to do?

A historian working on old films cannot conduct interviews with practitioners; time and death has put them beyond our reach. We can comb the archives for interviews from the time, but the results are often meagre. The interview with Christensen published in the Danish newspaper Politiken on 4 July 1923 from which I have already quoted a couple of times is the only one I have found where he talks about Seine Frau, die Unbekannte. The most striking thing he says about it is a comparison with his previous film: “it’s intended as an entertainment picture. That’s not what Heksen was, so to speak” (Anon. 1923a).

Heksen is the Danish title of Häxan, which was as noted previously, a radical, big-budget experiment. Häxan broke with conventional movie storytelling with its lecture-like structure, it required the development of groundbreaking special effects, and it was filled with all sorts of provocative material: nudity, blasphemy, body-snatching, child sacrifice, lewd demons, torture, devious and sex-obsessed churchmen, and much else. Censorship worries and interference held up the release of the film in many countries, including Germany, where it did not get released to the public until July 1924. The business strategy of Svensk Filmindustri, the production company, was very much aimed at the international market, and it was a major blow that this film, which had been a very long, arduous, and costly production, had so many troubles in getting released at all outside of Sweden and Denmark, where it premiered in the fall of 1922. Häxan’s commercial difficulties and Christensen’s remark taken together suggest that he felt needed to make a more commercial film.

A few weeks before the interview was published, a brief item in another Danish newpaper ascribes such considerations to Christensen: “After the dubious reception of Häxan, Benjamin Christensen has given up on major undertakings in film. He is now at work down in Berlin, where he is making a film in the genre of The Mystic X [sic] for UFA” (B.T., 19 June 1923). Christensen was indeed working in Berlin, and the working title Wilbur Crawford’s Wonderful Adventure may have mislead the reporter into thinking that it was a film “in the genre of” Det hemmelighedsfulde X, a spy melodrama. Yet while the report is clearly not particularly reliable, the idea that Seine Frau, die Unbekannte was a step back from the artistic ambitions on display in Häxan fits the critical consensus, both then and later.

To make use of the 1923 interview, then, we have had to supplement it with all kinds of other sources, including the films themselves. Hjort and her colleagues, however, concerned as they are to champion research interviews with contemporary filmmakers as a scholarly practice, appear to have reservations about the value of other kinds of evidence for researching the agency of practitioners, and particularly the evidence provided by the films themselves. If we take these misgivings at face value, they would seem to severely limit the usefulness to historians of the concept of practitioner’s agency.

Hjort and her colleagues do allow for the possibility of working from the films themselves: “Practitioner’s agency can be explored in a largely theoretical manner, with the film theorist postulating craft-related reasoning, and an implicit film author, on the basis of texual properties in a cinematic work or oeuvre” (Hjort, Jørholt & Redvall 2010: 15; original emphasis). The wording reveals, however, that they are skeptical of such efforts. The scholar proceeding in this fashion is labelled a “theorist,” the procedure “largely theoretical,” and their conclusions based on “postulating.” Indeed, they make their qualms explicit: “our sense being that a purely theoretical and inferential approach is ultimately inadequate” (Hjort, Jørholt & Redvall 2010: 15). They continue:

Put differently, any theoretical account of practioner’s agency is likely to be better, and more robust, if it is developed on the basis of empirical data that goes beyond what can be inferred from, or speculatively proposed on the basis of, an analysis of particular cinematic works. (Hjort, Jørholt & Redvall 2010: 15)

Thus, they use the term “theoretical” three times over in the space of two paragraphs to characterize an exploration of agency based on the works themselves. This sets up an evident rhetorical contrast with an exploration based on “empirical data” (i.e., filmmaker interviews). But if we turn to a work of film history like Kristin Thompson’s Herr Lubitsch Goes to Hollywood (2005), its account of different editing patterns in the early 1920s, based on the careful study of a large number of surviving films from the silent period, seems as empirically solid as anything in film studies.

Hjort and colleagues do not lay out in any detail what they mean by “theoretical” film analysis and how it is inadequate, but in a footnote to the sentence about “postulating […] an implicit film author,” we find an indication that they are not taking aim at historians like Thompson: “Scholars who come to mind in this connection are Jerrold Levinson and Noël Carroll” (Hjort, Jørholt & Redvall 2010: 30 n37). Levinson and Carroll are both philosophers, and they are key figures (along with Gregory Currie, Robert Stecker, and Paisley Livingston) in a long-running debate within philosophical aesthetics over art and intention. In a review of Livingston’s book Art and Intention (2005), Levinson describes the core of the debate as follows: “It is the issue of what determines the meaning of a literary work, or equivalently, of what the correct criteria are for interpreting a literary work” (Levinson 2016a: 137). In other words, the philosophers want to enable us to determine which interpretations of a given work are correct or at least valid, and which are not. In these debates, a particular point of disagreement is whether we should give any weight to the words of actual authors and filmmakers when they explicitly describe their intentions.

Currie and Levinson reject the relevance of interviews and other sources that give us clues about authors’ intentions, because they are not part of the work, and what interpretation should aim for is to establish the correct meaning of the work, not all kinds of other stuff. In opposition to the “moderate actual intentionalism” of Livingston and Stecker, Currie and Levinson refer to their position as “hypothetical intentionalism.” In a passage quoted and endorsed by Levinson, Currie explicitly states that interpretation involves postulating the meaning that our analysis finds the work to have, with the assumption that the work is what the author intended it to be: “Interpretation of the work aims to postulate communicative intentions for which the text can be seen as an adequate vehicle, and these will not always be the intentions the author actually had” (Currie 2004: 125; quoted in Levinson 2016b: 147). A film director may have said of some aspect of his or her film: I did not intend it to be ambiguous; but if interpreting it as ambiguous is more satisfying and meaningful, and the filmmaker could hypothetically have intended it to be ambiguous, the hypothetical intentionalist will say that the ambiguous interpretation is the correct one.

When Hjort and her colleagues voice misgivings against using the films themselves to investigate practitioner’s agency and belittle such efforts as merely “theoretical,” I believe that they are taking aim against the philosophical position of hypothetical intentionalism, not against historical study. It is important to recognize that the philosophers’ goal of establishing criteria for identifying valid interpretations of what works mean is quite different from that of film historians who seek to discover how works were made, what aesthetic problems they sought to solve, and how they fit into wider contexts of filmmaking norms, production cultures, and currents of social and intellectual life.

Herr Christensen Goes to Babelsberg

Some readers may still be concerned that a film-historical approach that focuses on practitioner’s agency may resemble an old-fashioned auteurist approach too closely. This would be a mistake. Admittedly, in her editor’s introduction to the anthology Film and Risk, Mette Hjort does draw a connection between thinking in terms of “practitioner’s agency or deliberative practices” and “the compelling case for renewed interest in cinematic authorship” made by Paisley Livingston and other intentionalist philosophers (Hjort 2012: 17). Nevertheless, it is worth stressing that neither she nor others who try to give the agency of practioners due attention would claim that a work’s meaning is determined by its maker(s), or that it is identical to the makers’ intentions.

I believe that most film historians are well aware that the works they investigate are not complete, closed objects. In order to make sense of a film, spectators had to bring with them all kinds of assumptions, background knowledge, and sense-making skills. The literary scholar John Farrell has made this point with respect to literature in his carefully argued book, The Varieties of Authorial Intention. He insists that the literary text is not independently meaningful without the reader’s active contribution to understanding it: “Language does not represent complete thoughts or meanings. It provides hints for their reconstruction in a particular context” (Farrell 2017: 33). Farrell objects strongly to seeing meaning as pre-packaged and given, decrying “the folly of our tendency to reify meaning in language, to see language as holding meaning, as if meaning were a substance that could be deposited in and extracted from a container” (Farrell 2017: 33).

Farrell focuses on language, but the point is relevant to other media of artistic expression. Indeed, David Bordwell made much the same point – including the objection against the metaphorical understanding of the text as a container for meaning – in 1989 in his book Making Meaning:

Comprehending and interpreting a literary text, a painting, a play, or a film constitutes an activity in which the perceiver plays a central role. The text is inert until a reader or listener or spectator does something to and with it. Moreover, in any act of perception, the effects are “underdetermined” by the data […] The sensory data of the film at hand furnish the materials out which inferential processes of perception and cognition build meanings. Meanings are not found but made. (Bordwell 1989b: 2-3)

Finding out how film practitioners produced these “sensory data” – rather than seeking to determine what they mean – is central to the kind of practice-oriented historical research Bordwell has long advocated.

If we adopt this kind of practice-oriented approach, we likely have a better chance of figuring out how Seine Frau, die Unbekannte might count as an “interesting experiment.” The film was shot at the old Union studio in Berlin, part of the UFA Templehof studio complex, according to the listings of ongoing productions in Lichtbild-Bühne, while the filmography in the authoritative Das UFA-Buch indicates that exteriors were shot on the Babelsberg lot (Bock & Töteberg 1992: 118). 1 At the time the film was shot, German studio filmmaking was in the process of adopting American ligthting techniques. These were based on “dark” studios, where all natural light was excluded, allowing full control of the completely artificial illumination, whereas some German films were still being shot in glass studios, using sunlight. The Union and Messter glass studios at Templehof had recently been converted to dark studios by painting over the glass with blue paint: “The glass roofing has been covered with blue paint everywhere to avoid any disturbing (sun-) side-light, and at one of the studios they have even gone over to constructing the ceiling from massive stones” (A. Kossowsky: “Die Filmateliers der Ufa in Berlin-Tempelhof,” Kinotechnische Rundschau, no. 22, Film-Kurier, no. 239, 9 October 1924; quoted in Bock (1987)).

Kristin Thompson has discussed the limited use of artificial lighting in German films of the early 1920s in some detail in her book Herr Lubitsch Goes to Hollywood. She studied a very substantial number of surviving films for this book, including Seine Frau, die Unbekannte, though she does not mention it specifically in the text. By the early 1920s, Thompson observes, the use of back-lighting had become standard in Hollywood: “Lamps could be placed on the top of sets at the rear or directed through windows or other openings in the sets; these would project highlights onto the actors’ hair and trace a little outline of light around their bodies, often termed ‘edge’ light” (Thompson 2005: 39). The edge light makes actors stand out from the background, focusing our attention on them, but in German films, it was not in general use. Thompson has found a few examples but argues that Lubitsch was the real trailblazer: “Few, if any, German filmmakers took to American-style lighting as quickly as Lubitsch did, and his transitional films [Das Weib des Pharaoh (1922); Die Flamme (1923)] seem to have been held up as models to be emulated” (Thompson 2005: 49).

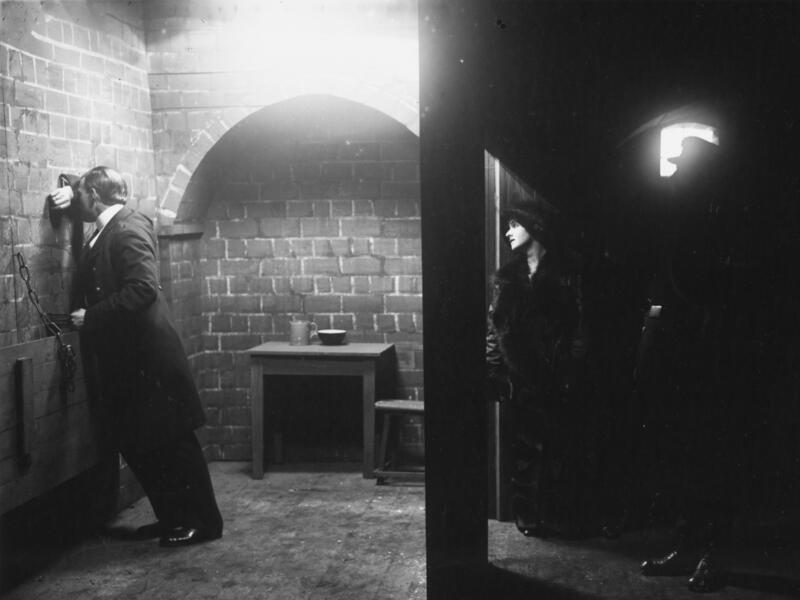

In Seine Frau, die Unbekannte, however, Christensen uses edge lighting frequently if not consistently. The effect is perhaps most striking in the scene where Eva models for Wilbur in the nude, but it also occurs in a number of more ordinary dialogue scenes. A point of comparison can be found in a film being shot at the same studio facility (Union) at the same time (August 1923) as Seine Frau, die Unbekannte:F. W. Murnau’s Die Finanzen des Grossherzogs (DE 1924). While there is quite a bit of side lighting in Murnau’s film, it contains hardly any shots that use edge lighting. Christensen had of course from the beginning of his career been interested in exploring the dramatic and atmosphere-creating potential of lighting, and while Seine Frau, die Unbekannte does not include the kind of bravura silhouette effects we find in many of his other films, the lighting is more remarkable than we might think at first glance.

Seine Frau, die Unbekannte, then, is not far behind Lubitsch in its adoption of advanced American filmmaking techniques. In that light, I think this is where the most likely explanation lies for why the reviewer in Der Kinematograph described Christensen’s film as an “exceedingly interesting experiment, particularly from the perspective of the German film producer.” Emulating and equaling Hollywood craftsmanship was a goal many German commentators urged their filmmakers to pursue. For Christensen, this was probably a calculated risk: on the one hand, it would probably have been easier and cheaper to shoot the film in a more old-fashioned style; on the other hand, Christensen’s technical mastery was an important part of his reputation as a top filmmaker. He clearly wanted the film to be able to hold its own on the “international” market – which meant in practice that the film would have to be able to hold its own in direct competition with American movies.

Christensen also had to consider whether he could hold his own among the filmmakers of Hollywood. In the 4 July 1923 interview, he speaks of his plans to go to the United States to market Häxan at the beginning of 1924. The interviewer asks: “You have not received any offers to become a director in the movie-land of California?” Christensen responds: “Yes, actually, I have! But let’s talk about that another time when I know what comes of it. My train is in half an hour” (Anon. 1923a). Christensen’s coy reply suggests that he was actively thinking about pursuing a career in Hollywood; he would eventually arrive at MGM in February 1925. Still, with this in mind, trying to make Seine Frau, die Unbekannte as “American” as possible would seem to be a sensible strategy.

Even if he wanted to make an entertainment picture, a straightforwardly commercial movie, Christensen had a reputation to protect as an innovator and stylist. Pursuing this kind of technical innovation would not, however, have been a risk-free strategy for Christensen. He was a foreigner, working in a new and bigger film industry with more supervision and control. A year later, after the film had proven successful, he was saluted as an honorary ‘German’ filmmaker: “And today we can readily number Herbert Wilcox as well as the two Danish directors Benjamin Christensen and Carl Th. Dreyer among our own” (Lichtbild-Bühne vol. 17:28b, 17 July 1924: 1). But when he was making it, he had to realize that breaking with established routines might have been costly and caused the production to fall behind schedule.

The shooting of Seine Frau, die Unbekannte does seem to have taken longer than anticipated. The sources are contradictory: in mid-May, when Christensen’s name first appears in Lichtbild-Bühne’s list of ongoing productions, the planned completion date is given as “End of May” (LBB v16:20, 19 May 1923: 30), just two weeks away, which seems unrealistic unless the plan had been to transfer the production to another facility. In early July, Christensen tells Politiken’s interviewer that he is “very, very close to completing” the film: “We only have some exterior shots still to do. There hasn’t been a lot of sun this summer” (Anon. 1923a). Yet Lichtbild-Bühne continues to list the production as ongoing until 20 September (v16:37b). The delays may have had more to do with the German economy going into hyperinflationary tailspin than anything Christensen did. The cover price of Lichtbild-Bühne’s twice-weekly “Tagesdienst” supplement illustrates the development. In mid-May, it cost 50 Marks (already a hefty sum), rising to ten times that at the beginning of August; by 20 September, when Christensen completed production, the cover price was 250,000 Marks, eventually topping out at 5 billion Marks two months later.

Mette Hjort has urged film scholars to pay more attention to risk and the way it pervades the making and even the reception of films (Hjort 2012). To understand the agency of film practitioners also involves an appreciation of the risks they take on. John Farrell, the literary scholar, is also concerned to stress “the factor of risk that accompanies all human action” (Farrell 2017: 10). The work of cinematic practitioners carries inherent risks of failure: “Any act of communication involves the possibility of being misunderstood, and any act of artistic making involves the possibility of failing to produce the intended impact” (Farrell 2017: 10). An important part of examining films historically, I would argue, consists in clarifying the choices and stakes that faced the people who made them.

The biggest risk Christensen took with Seine Frau, die Unbekannte was probably that of making a romantic comedy about an invalided veteran and a war widow – something which could easily have seemed in very poor taste. There were great numbers of war invalids in 1923 Germany, although the blinded made up a relatively small proportion of the total number. According to official figures, out of 700,000 non-fatal casualties, around 90,000 were categorized as “mutilated” (“Verstümmelte”) with the right to special compensation. The great majority of these had lost limbs or the use of them. Those who had lost their eyesight on both eyes numbered 1445 (Eckart 2014: 584). These figures are incomplete; they set the number of the dead at 1.2 million, while the true number of German military deaths may have been in excess of two million (Overmans 2014: 665). Still, they give a sense of the scale of the losses. Many audience members would have lost loved ones in the war or be obliged to care for those returning with serious injuries.

In this context, there would seem to be a clear risk of spectators reacting negatively to the film’s combination of melodramatic sentiment and frivolity. Graham Petrie, one of the few film historians to write even in passing about Seine Frau, die Unbekannte, clearly finds it objectionable: “The tone of the film is very uncertain, presenting potentially painful and emotionally disturbing scenes in terms of rather heavy-handed comedy, and the chance to explore the inherent masochism of the wife’s behavior is passed over in favour of some superficial role- and game-playing” (Petrie 1986: 158). Ib Monty describes the film’s plot as “bizarre” and “absolute nonsense,” but begrudgingly admits that the German reviewers were “surprisingly friendly” (Monty 1999: 48). The German press was, in fact, “full of praise” for the film (Stiasny 2018: 2). No reviewer objected to the light-hearted treatment of a serious subject, and the film was lauded for its sureness of tone: “Christensen has created a sophisticated comedy film, its contours drawn with subtlety, with soulful humor and that touch of sentiment that is inseparable from the essence of comedy” (Michaelis 1923; reprinted in Stiasny 2018: 3).

Conclusion

Christensen’s limited risk-taking seems to have paid off with a solid commercial success. Looking at the broader issues, I hope to have shown that thinking in terms of practitioner’s agency makes a lot of sense for film historians, and that the concept has certain advantages compared to Bordwell’s rational-agent model. The emphasis on interviews does confront historians with certain difficulties, but it also underscores the value of surviving interviews as historical sources, encouraging film historians to dig for them and to pay attention to them when they discover them. We have seen how the Politiken interview with Christensen, however brief and commonplace it might seem, turns out to be relevant to style, casting, the film’s production schedule, and much else. Interviewing Christensen was an obvious thing to do, the interviewer writes, “because of the interest that always attaches itself to the doings and undertakings of this filmmaker” (Anon. 1923a).

In the end, we should not exaggerate the differences between the two models we have examined. Bordwell is clear about the value of filmmakers’ pronouncements on their artistic decision-making, whether in writing or interviews: “Filmmakers have reflected, to various degrees of detail, upon their creative choices, and this literature offers a rich legacy of insights into practices” (Bordwell 2008: 28). And I am sure he would agree with Mette Hjort that not only does it make sense to listen to what filmmakers have to say about their own practice, it is ethically proper as well: “if a film’s makers and collective authors are willing to pronounce on these matters, we owe it to them to take what they say seriously, at least as a starting point for discussion” (Hjort 2010: 117, emphasis added). This moral case for paying attention to practitioner’s agency is echoed by John Farrell, who as we saw insists on the contribution of the audience to the work. “Writing of any kind,” he says (and the point applies equally to other kinds of artistic practice), “is an intersubjective public practice, not the mere projection of personal subjectivity.” And both artist and audience are real, historical individuals: “an intersubjective public practice requires a real practitioner and a real public, and to leave these out, to reduce either to a mere function of textuality, is to dehumanize the activity in question. It is to eliminate the once-living hand and voice” (Farrell 2017: 10). As film historians, we seek instead to show the practitioner’s hand at work.

Notes

1. Since the interiors comprise most of the film, the title of this section should perhaps have been “… Goes to Templehof,” but that name is more evocative of aviation than of filmmaking.

Works cited

Anon. (1923a). “Benjamin Christensen i Tyskland: Interview med ‘Heksen’s forfatter.” Politiken, 4 July.

Anon. (1923b). “Was der Winter bringt: Die Verleih-Programme für die neue Saison.” Lichtbild-Bühne 16(36): 8-10.

Bock, Hans-Michael. (1987). “Berliner Film-Ateliers: Ein kleines Lexikon.” Retrieved 5 November, 2019, from http://www.cinegraph.de/etc/ateliers/index.html.

Bock, Hans-Michael and Michael Töteberg, eds. (1992). Das Ufa-Buch: Kunst und Krisen, Stars und Regisseure, Wirtschaft und Politik. Frankfurt a.M., Tweitausendeins.

Bordwell, David (1988). Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema. Princeton, N.J., Princeton University Press.

Bordwell, David (1989a). “A Case for Cognitivism.” In: Iris(9): 11-40.

Bordwell, David (1989b). Making Meaning: Inference and Rhetoric in the Interpretation of Cinema. Cambridge, Mass., Harvard University Press.

Bordwell, David (2008). “Poetics of Cinema”, Poetics of Cinema, 11-55. New York, Routledge.

Chang, Ha-Joon (2014). Economics: The User’s Guide. London, Pelican.

Currie, Gregory (2004). “Interpretation and Pragmatics”, Arts and Minds, 107-133. Oxford, Clarendon Press.

Dagover, Lil (1979). Ich war die Dame. München, Schneekluth.

Donnelly, Sophie (2018). “Homo Oeconomicus: Useful Abstraction or Perversion of Reality?” In: Student Economic Review 32: 95-104.

Eckart, Wolfgang U. (2014). “Invalidität”. In: Gerhard Hirschfeld, Gerd Krumeich, Irina Renz and Markus Pöhlmann (ed.), Enzyklopädie Erster Weltkrieg, 584-586. Paderborn, Schöningh.

Elster, Jon (2009). “Interpretation and Rational Choice.” In: Rationality and Society 21(1): 5-33.

Elster, Jon (2018). “From Marx to Emotions.” In: Tidsskrift for Samfunnsforskning 59(2): 201-213.

Farrell, John (2017). The Varieties of Authorial Intention: Literary Theory Beyond the Intentional Fallacy. Cham, Palgrave Macmillan.

Fritsch, Willy (1963). ...das kommt nicht wieder: Erinnerungen eines Filmschauspielers. Zürich, Werner Classen.

Hjort, Mette (2006). Stanley Kwan’s Center Stage. Hong Kong, Hong Kong University Press.

Hjort, Mette (2010). Lone Scherfig’s Italian for Beginners. Seattle, Wa., University of Washington Press.

Hjort, Mette, ed. (2012). Film and Risk. Detroit, Mich., Wayne State University Press.

Hjort, Mette, Eva Jørholt and Eva Novrup Redvall (2010). The Danish Directors 2: Dialogues on the New Danish Fiction Cinema. Bristol, Intellect.

Hjort, Mette and Ursula Lindqvist, eds. (2016). A Companion to Nordic Cinema. Chichester, Wiley-Blackwell.

Levinson, Jerrold (2016a). “Artful Intentions”, In: Aesthetic Pursuits: Essays in Philosophy of Art, 133-144. Oxford, Oxford University Press.

Levinson, Jerrold (2016b). “Defending Hypothetical Intentionalism”, Aesthetic Pursuits, 141-162. Oxford, Oxford University Press.

Livingston, Paisley (2005). Art and Intention: A Philosophical Study. Oxford, Clarendon Press.

Michaelis, Heinz [M-s.] (1923). Review of Seine Frau, die Unbekannte. In: Film-Kurier no. 238, 20 October.

Monty, Ib (1999). “Benjamin Christensen in Germany: The Critical Reception of His Films in the 1910s and 1920s”. In: John Fullerton and Jan Olsson (ed.), Nordic Explorations: Film Before 1930, 41-55. Sydney, John Libbey.

Overmans, Rüdiger (2014). “Kriegsverluste”. In: Gerhard Hirschfeld, Gerd Krumeich, Irina Renz and Markus Pöhlmann (ed.), Enzyklopädie Erster Weltkrieg, 663-666. Paderborn, Schöningh.

Petrie, Graham (1986). Hollywood Destinies: European Directors in America, 1922-1931. London, Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Shaviro, Steven (2008). “The Cinematic Body REDUX.” In: Parallax 14(1): 48-54.

Stiasny, Philipp (2018). Seine Frau, die Unbekannte: Program Notes. Berlin, Zeughauskino. Retrieved 3 August 2019, from https://www.dhm.de/zeughauskino/programmarchiv/materialien/filmeinfuehrungen-weimar-international.html.

Thompson, Kristin (2005). Herr Lubitsch Goes to Hollywood: German and American Film after World War I. Amsterdam, Amsterdam University Press.

Tybjerg, Casper (2005). “The Makers of Movies: Authors, Subjects, Personalities, Agents?”. In: Torben Grodal, Bente Larsen and Iben Thorvig Laursen (ed.), Visual Authorship: Creativity and Intentionality in Media, 37-65. Copenhagen, Museum Tusculanum.

Tybjerg, Casper (2016). “Devil-Nets of Clues: True Detective and the Search for Meaning.” In: Northern Lights 14, 103-121.

Suggested citation

Tybjerg, Casper (2020), Benjamin Christensen’s Wonderful Adventure: Film History and Practitioner’s Agency. Kosmorama #276 (www.kosmorama.org).

Watch the films at 'Stumfilm.dk':