Acerbic headlines and stinging commentaries abounded when Eduard Schnedler-Sørensen’s film Grænsefolket (People of the Borderland) was banned by the Danish censors on 19 December 1925. It was not just that the film had been “anticipated with more than the usual interest” and had cost 100,000 kroner to make. It was also the case that the “categorical ban” was announced as late as the day before the film’s planned “world premiere at Palads Theatre in aid of the National Museum Fund”. All this was reported on 19 December by the newspaper Dagbladet, under the headline “Censor bans the national film of Southern Jutland”.

The newspaper had interviewed Anton Nicolaisen, one of the three film censors in post in Denmark, as well as the screenwriter of the film, Laurids Skands. The latter declared:

I find the ban quite unreasonable … I cannot see that the novella by Seedorff on which the film is based is anything other than an act of infinite beauty by the author in its depiction of the history of suffering of the Danes of Southern Jutland. It has also been accorded recognition by Dr Knud Rasmussen on behalf of the National Museum.

So the literary inspiration from Hans Hartvig Seedorff was, according to Skands, noble enough; the film was approved by Knud Rasmussen, who at that point in the mid-1920s was celebrated by as much by the people as by the establishment in the wake of his Thule expeditions; and even the premiere had been worthily organised as a gift to the National museum. The expansive and expensive film had indeed been funded by the National Museum Fund (Sandfeld 1966: 467). And this was a case of a “national film”, which portrayed the conditions endured by the stout Southern Jutlanders during the First World War, when Danish-minded folk from what was then the German territory of North Schleswig were forced to fight on the side of Germany.

The press polemic about the censoring of The People of the Borderland had begun to simmer as early as that autumn. A newspaper serving the German minority in the region, Neue Tondernsche Zeitung, had got wind of the film production and in an article of 16 August referred to the film as “Danish incorporation propaganda” — and what was to be “incorporated” was the part of Southern Jutland that the New Tønder-ish Times regarded as ‘North Schleswig — that is, German land north of the recently revised border, a border which Germany had never officially recognised. Sonderburger Zeitung seconded its fellow paper on 25 August, calling The People of the Borderland “an anti-German witch hunt of a film”. For several Danish newspapers, the film and its censorship were also clearly subjects of national interest. Confronted by the reporter from Dagbladet on 19 December, censor Nicolaisen attempted to defend the evaluation of the film: the three film censors were unanimous, and “the most important factor in that decision is that the film will inspire unrest when it is screened in the borderlands”, he said. The film could open old wounds between Denmark and Germany. But the very same day, rumours were flying in several newspapers to the effect that it was not the censor’s office that had banned the film, but the Foreign Ministry. Nicolaisen was also asked about this:

I do not wish to comment on that. That we have, as is usual in very difficult cases which touch on politics and religion, sought advice from others, I am willing to admit. But the judgement is ours, and we stand by it.

But it was a judgement arrived at under pressure, recounted the newspaper Nationaltidende on what should have been the day of the premiere. “It was soon apparent that the ban was enacted after persistent representations on the part of the Foreign Minister, Count Moltke”, while the newspaper also claimed that the German ambassador, Baron von Mutius, had attended the censors’ viewing of the film. So it was not just the case that the Foreign Office had involved itself in film censorship, a matter which was the domain of the Ministry of Justice, but the German ambassador, too, seemed to have placed his finger on the scale. The next day, 20 December, Aarhus Amtstidende stuck its oar in with a report that the Prime Minister and Minister of Justice, “Messrs Stauning and Steincke, as well as various civil servants, have seen the film and found it offensive”.

The film was thus caught up in the problem of the Danish-German borderlands in a very concrete way, and thematically it focused on the experience of the national minority during the war that led to the plebiscite and the revision of the border in 1920. While we might expect a relatively free back-and-forth between the nations in the case of films not featuring national-political content, on the other hand a film about the Danish-German flashpoint in the border region can be regarded as a litmus test for what we often assume to be a common film culture shared by the two countries in the silent era. This article, then, begins by analysing the events surrounding the ban on The People of the Borderland, and then goes on to examine how Danish-German political relations influenced which foreign films were censored in Denmark in the 1920s.

The polemic surrounding the forbidden film

What was so offensive about the film, that is, the basis on which the censors, government civil servants and ministers had justified the ban, was outlined a little more clearly by Aftenposten on 19 December 1925. Censor Nicolaisen provided the following example:

…German officers are always depicted holding a beer, and we see them treat the film’s heroine as anything other than a lady. Moreover, the Danish hero is presented to too great an extent as engaged in agitation and spying, while the Southern Jutland leaders during the debate in the German Reichstag actually emphasised the Danish Southern Jutlanders’ loyalty. We cannot countenance this being misrepresented.

Aftenposten was a Copenhagen newspaper, and it accepts in good faith the concern that the film could spark a reaction in the border region. But the journalist did not buy Nicolaisen’s rejection of the idea that it could be feasible to enforce a ban on the film locally in Southern Jutland. That position was declared “unconvincing” by the newspaper, and the metropolitan journalist concludes by declaring: “the film ought to be released here in the city, and it should be shown publicly!”

This opinion, however, was not shared by all the journalists who had actually seen the film before the cancelled premiere. Under the headline “The forbidden film”, the Jutland-based Jyllands-Posten listed on 20 December the reactions of various newspaper reviewers to the film itself, and they are anything but positive: Kristeligt Dagblad, for example, harshly condemns The People of the Borderland, while Berlingske Tidende offers the following verbal shrug of the shoulders: “Now that the judgement of the censors has been laid down, at least there is the advantage that a central and progressive episode in the recent national history of our people will not be publicly banalised.” But although this newspaper did not believe that filmgoers were missing out on a great work, nonetheless “the whole business of the ban is, to say the least, tiresome for us as a nation. The Germans will crow, and in other countries they will shrug their shoulders with an obvious scorn for Danish pant-wetting.”

Neither did the ban fall on good soil in the otherwise fertile borderland of Southern Jutland: the metropolitan newspaper Berlingske printed a selection of comments from the newspapers of the border region on 20 December. Dybbølposten found the controversy “quite meaningless” and the discussion of whether the film could be banned only in Southern Jutland and shown in the rest of the country was dismissed as follows:

We are really not that sensitive down here. Our relationship with Germany is not going to be up-ended by a single episode, and it is thus no more risky to show The People of the Borderland here than it is in other parts of Denmark.

In Haderslev Stiftstidende the editor, Mr Svensson, expresses his “astonishment that a couple of ministers, of which one was the country’s Foreign Minister, found it necessary to act as film censors”. That kind of work, thought Svensson, should fall only on the film censors themselves, and “it does not look good, neither on the Danish nor the German side, that government ministers are acting as functionaries in the relationship between Denmark and Germany.”

An international perspective on the kerfuffle about The People of the Borderland was offered by the British Manchester Guardian, whose Berlin correspondent had heard about the affair. In the report he sent home, he described the film as bearing a “strong anti-German bias”, and as “really a piece of damaging nationalistic propaganda”, as quoted by Haderslev Amtstidende on 29 December. Exactly how a British correspondent in Berlin had been able to view the film, when it had not been screened outside the premises of the censors, remained something of a mystery, and one which the newspaper did not bother to mention. On the other hand, some detail is provided about how the Manchester Guardian discussed the ban as an example of

...the unusual political propriety of the Danes, though they are in no way German-friendly. In fact, they stood very strongly on the side of the Allies during the War. Nevertheless, they have treated the German minority in the region of Northern Schleswig that was returned to Denmark after the plebiscite with unrivalled tolerance and nobility.”. 1

The episode could thus be exploited for glorification of the Danish national character just as well as it could for a swipe at “pant-wetting”, according to temperament and point of view. After comprehensive re-working, The People of the Borderland had its premiere in March 1927. A year earlier, rumours had begun to circulate that the film might be released in Denmark after all. One such report appeared in B.T. on 7 January 1926, in which censor Nicolaisen was quoted as saying that a re-edited version would not have much chance of making it past his and his colleagues’ desks. It was not just a matter of re-editing the film, as a solution to the ban. There would need to be new and expensive scenes shot and more cutting, which Nicolaisen thought was unlikely. Despite his reservations, a new version of the film was approved for exhibition just over a year later. But although the film was liberated, the Foreign Ministry still sought to supervise its circulation, not least in Paris in 1929, where it won a certain renown among reviewers; they saw in the film a clear parallel with the disagreements about the French-German border region of Alsace-Lorraine. The Danish Embassy in Paris declined to be officially represented at the premiere of the revised film; as phrased in a note from the Foreign Ministry to the Press Attaché in Paris, The People of the Borderland was still regarded as “an appeal to international chauvinism”. In the same letter, the Ministry applauds the ambassador for declining to attend the premiere. 2

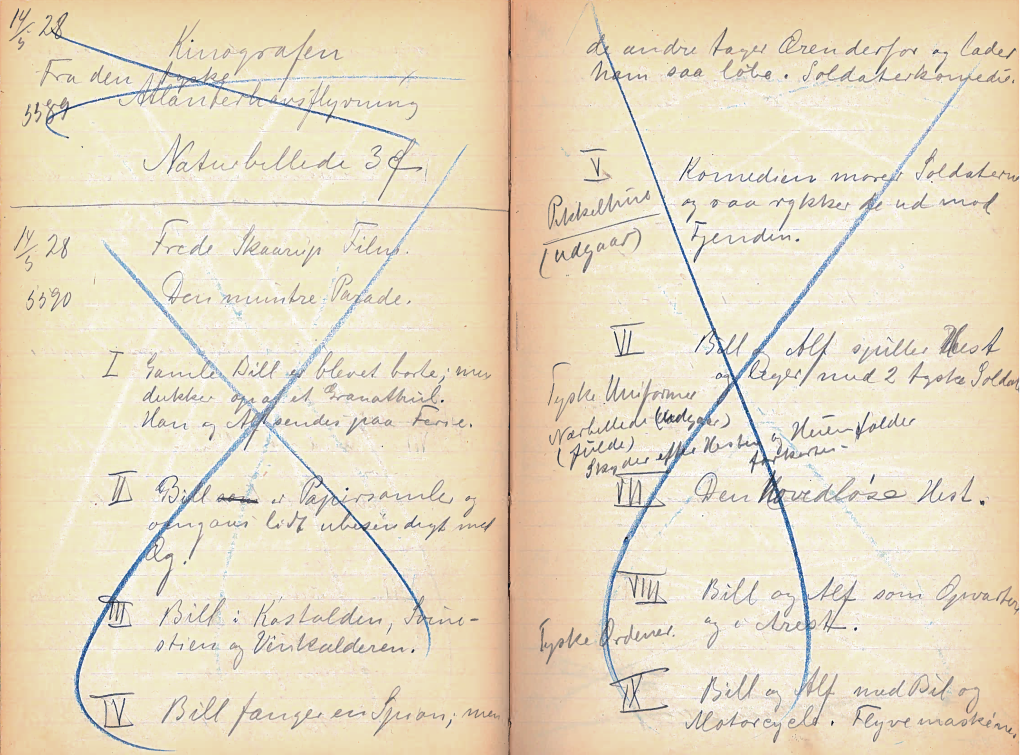

It is impossible to discern how the approved version of the film differed from the banned version, as neither of them have survived as complete films. But it is clear that new footage was added and other scenes were cut, because the 1927 version was 2550 metres long, while in 1925 Nicolaisen had jotted down in his censor’s notebook that the film’s length was 2514 metres. Nicolaisen’s two pages of notes on The People of the Borderland consist almost entirely of plot summary, without any judgmental or prejudiced remarks. It is an unusually objective and brief treatment, which perhaps indicates that he and his colleagues knew even while they were viewing the film that they would not have the final say on its fate. Nicolaisen was otherwise generally conscientious about noting his straightforward opinions about scenes and sequences in a film, while he was engaged in censoring it. The example below of Nicolaisen’s notes from the censorship process of the film The Better ‘Ole (Charles Reisner, USA, 1926; Danish title Den muntre Parade) shows that in 1928 he was on guard against any visual elements that signaled German-ness. In the notes, he observes both “Pikkelhuer” (Pickelhelm or Prussian army helmet) and “tyske uniformer” (German uniforms) which “udgaar” (are to be removed). And the same elements were in evidence in The People of the Borderland, at least if we are to judge by the surviving stills and posters, so if Nicolaisen was consistent, he would have been inspired to note them down — but he did not.

Danish “pant-wetting”?

If we want to understand why the controversial ban was applied to Schnedler-Sørensen’s film, the surviving fragment of the film’s closing scenes provides a few hints. The fragment shows very clearly that the film ends with a pathos-laden national celebration of the German defeat. But we cannot know whether this is a piece of the 1925 version, or of the re-worked film. Scenes that could provide a sense of how the German officers, for instance, were portrayed have not been preserved. Naturally, that so little of the film has survived means that any conclusions we might draw about the content of either version of The People of the Borderland can only be tentative at best.

Fragment: Grænsefolket (The People of the Borderland, Eduard Schnedler-Sørensen, Denmark, 1925/1927).

The version of the screenplay that has survived seems to confirm censor Nicolaisen’s judgement that the portrayal of German officers and German-minded residents of the border region was blatantly anti-German, an impression corroborated by the Berlin correspondent of the Manchester Guardian, as previously mentioned. At the centre of the narrative is the Danish-minded Uwesen family, who own a farm in the small town of Tyrstrup. The sons of the family are called up for German military service, and black thunderclouds loom over the town while news of the first German victory arrives. In the local tavern, German officers, grasping the beer bottles that Nicolaisen noted, celebrate the good news together with German-minded civilians:

…here sat the baker, the carpenter and the German merchant and stared as if bewitched at Butcher Weber’s fingers, round and plump as Bavarian sausages, which were sketching out the western front in the puddles of spilt beer (Skands 1925: 21)

In this extract, the screenwriter Laurids Skands plays what we might call the ‘German sausage card’ — one of the most widespread anti-German stereotypes — in his characterisation. The physical appearance and actions of the town’s most senior German authority, the district judge Sternmayer, are also crudely portrayed. The day after the young Danish-minded recruits are forced to leave for the front, Sternmayer rounds up men from “suspicious families” for interrogation. These include the Danish-minded locals who do not share the German joy at the outbreak of war, such as the village blacksmith and farmer Uwesen from Tyrstrup Farm — two of their sons had run away the previous evening. The judge is described thus: “District Judge Sternmayer mopped his hot, ruddy face, rolls of fat neck undulating out over the tight collar of his uniform.” A fat German, obviously. And police officer Schultze, who assists the judge during the hearing, is caricatured like this: “‘National feeling, lukewarm’ [Schultze] commented, with emphasis on the term ‘lukewarm’, as though the very word excited his longing for a tankard of pilsner from a cool cellar” (ibid: 15). Once again, German thirst for beer is part of the character treatment. But it is not just that the Germans in the screenplay are fat and crave beer; some of them are scarcely human. The day before the departure for the front, one of farmer Uwesen’s sons flees together with a son of the blacksmith; the latter is shot through the head. Just after the fatal shot, this scene unfolds:

Down on the coast, all was quiet. But on the shore stood a small, crippled figure. In its face, as if contorted by an almighty hatred, the eyes glittered like black coals, while they tried to follow a boat gliding out over the sea with powerful strokes of the oars. (ibid: 7)

The sniper, a German border guard, judging from the context, is portrayed by Skands here as decidedly un-human: “a crippled figure” whose face is referred to as “its”, not “his”. And so what we have here is an animal, or rather, a monster.

In other words, there is enough in the manuscript to suggest that Schnedler-Sørensen directed his first version of the film based on a screenplay whose author, Laurids Skands, produced a strongly anti-German text. The ideas underlying the manuscript are clear: the Germans are monsters or at least fat, drunken tyrants, whereas the Danes are the plucky underdogs. There is, however, one exception worthy of note: judge Sternmayer’s son and daughter attempt to help the Uwesen family when the judge confiscates the farm and auctions off their belongings. The younger generation, then, is not characterised in simple, black-and-white terms of inherited enmity.

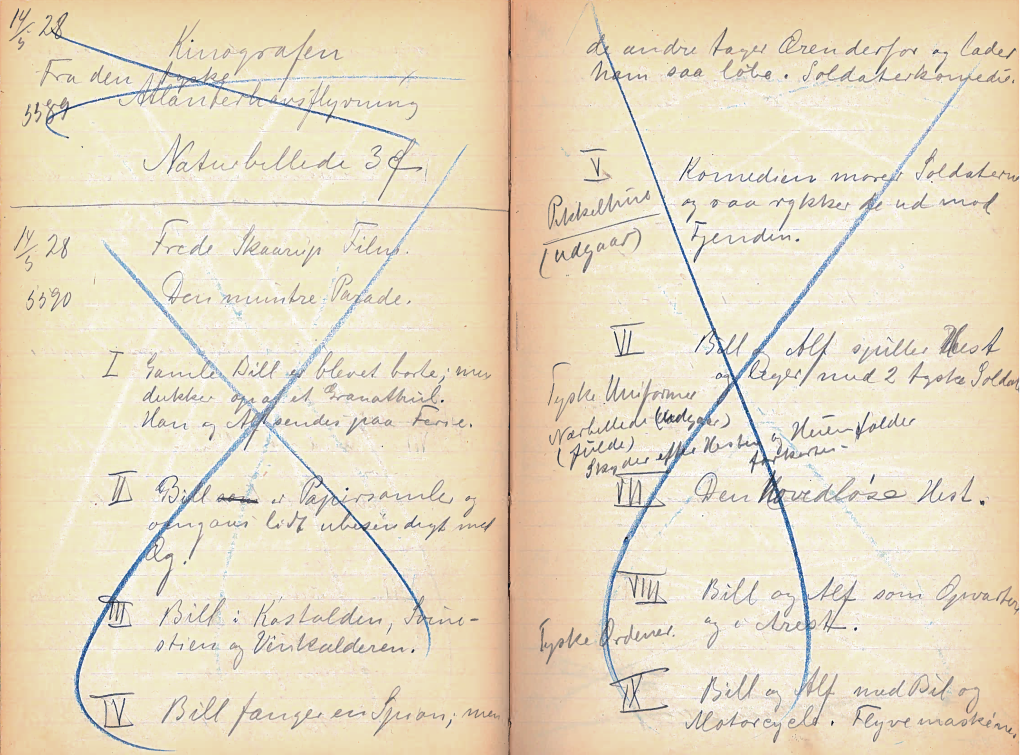

A screenplay is one thing; quite another is how a film director interprets the written text, and which actors are cast to bring the manuscript to life. The surviving fragment and stills from the film clearly show that the character of judge Sternmayer is a strict gentleman wearing stern steel-rimmed spectacles above his Prussian handlebar moustache. But as played by actor Peter Nielsen, the judge is neither fat nor in uniform.

Sternmayer’s son Heinrich, played by Alex Suhr, stands out clearly as the young officer type described in the screenplay. Neither the German officers nor the punters in the tavern are obviously overweight (or sausage-like, as the manuscript would have it).

To judge from the visual material that has survived, then, the journey from manuscript to screen diluted the harshest stereotypes. The question, however, is whether the preserved stills originate from the first or second versions of the film — we do not know, because the Danish Film Institute’s collection contains some photos stamped by Statens Film Censur (the State Film Censor) as well as some with no such stamp. Those with a stamp can be said with certainty to come from the approved version, but it is impossible to tell whether the un-stamped images were not intended for use in publicity, and thus not submitted to the censor, or whether they date from the original banned version.

If we want to understand the central justification for completely banning the film instead of merely editing it, it is not enough to focus on isolated scenes and characters. According to censor Nicolaisen, it was the overall approach of the film that motivated the ban. Reading the preserved manuscript throws up ample grounds for Nicolaisen’s decision. The story as a whole not only depicts German tyranny and the cruelties suffered by the Danish-minded soldiers called up to the front and their oppressed families at home. It also emphasises the Danish nationalist celebrations when the German defeat becomes a reality. News of the loss comes to the people at Tyrstrup Farm in the form of a communiqué transported by plane. As the Danish flag is raised again, the screenplay references the legend of how it fell from the heavens in 1219:

It was the first message from the new Germany to Southern Jutland: permission to hoist the old flag. They rushed out. They hugged each other until they could scarcely breathe, such was their boundless joy. But when the flag, raised by Edvard, quietly glided to full mast, there was quiet. Their eyes were fixed on the cloth as it slowly caught the wind and flew against the sky from which it had fallen (Skands 1925: 47)

Justice is eventually done, but in the face of great loss, which leaves its mark on the faces of the older generation as steely Danishness. Meanwhile, in the film’s contemporary frame narrative, the children of the line enjoy their freedom in a meadow in which ancient grave mounds rise from the soil of their fatherland. The old grandmother of the estate pronounces a final warning to the young: “You must love your own country, and never forget those who won it back for you…”. What is essential here is that the Danes have an ancestral right to the soil — which their German-minded neighbours do not. That this message is not reproduced in the inter-titles of the surviving fragment is not in itself proof that the footage stems from the approved version, because a finished film’s inter-titles often diverged from the manuscript. Either way, we can see that there was more than enough material in the film to warrant a crackdown by any censor, civil servant or minister who wanted to avoid giving umbrage to the German-minded minority in the border region, or indeed the German Embassy in Copenhagen.

“The German necessity”

In a book by the film historian Gunnar Sandfeld, Den stumme scene ('The Silent Stage', 1966: 466 ff.), the controversy surrounding The People of the Borderland is described as an instance of “the German necessity”: a distinctive wariness about not offending German national sentiment, which informed the behaviour of the Danish censor and state officials alike during and after the First World War. According to Sandfeld, this was a phenomenon with no equivalent in regard to other nations. He points to examples of complaints from Chinese and Mexican diplomats about how their compatriots and cultures were represented to Danish cinema-goers, complaints which were ignored by the censor and the relevant government ministries (Ibid: 468). Sandfeld claims, then, that it was only in relation to Denmark’s German neighbours that the State intervened through film censorship. However, rifling through the archives of the Foreign Ministry’s Press Office, on which Sandfeld draws, it transpires that the Foreign Ministry’s nitpicking and the politicised censorship were not only in evidence in the case of The People of the Borderland. For example, in one case the Foreign Ministry intervened in the process of theatre censorship under pressure from the French Embassy, 3 which indicates that it was not exclusively the Germans who benefited. The archives also show that it was not only the Danish state that interfered when the German press and authorities protested against films they saw as anti-German.

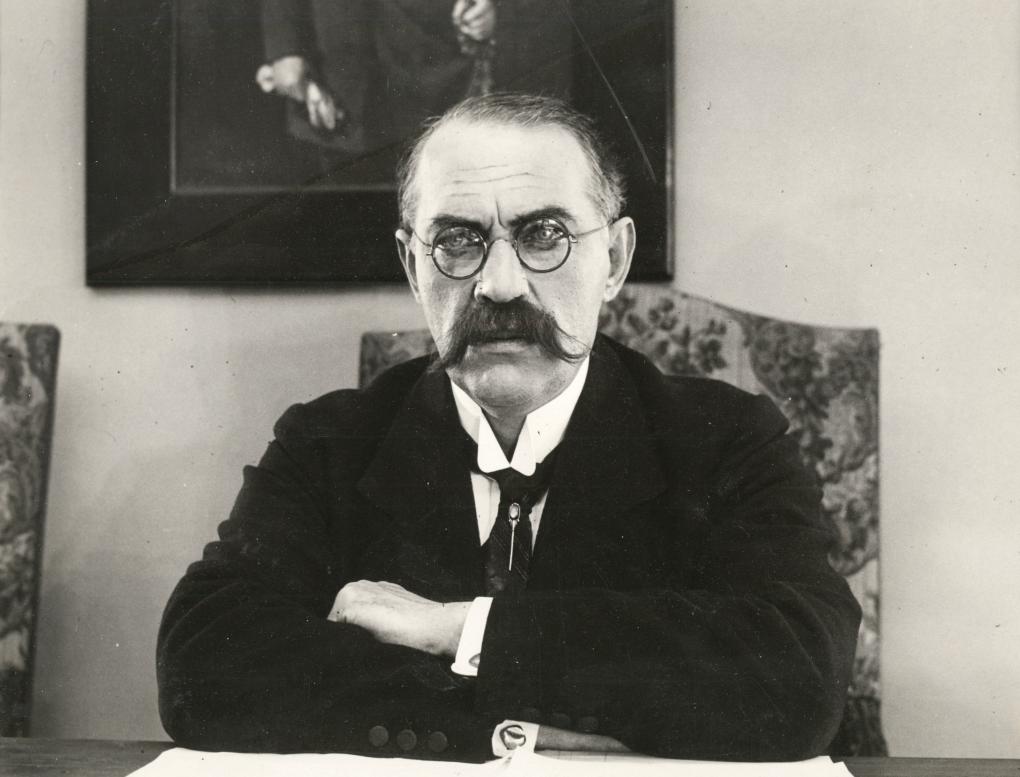

In March 1929, the Danish film censor — once again acting in consort with the Foreign Ministry — was to assess the British film Dawn (Herbert Wilcox, 1928). Schnedler-Sørensen planned to distribute the film in Denmark on behalf of Fotorama. He had submitted the film for a so-called ‘test censorship’, which means that he was asking the censors for an unofficial judgement on whether Dawn could be screened in Denmark. This was a sensible way to proceed, because the film was controversial. The ‘unofficial test censorship’ made it possible to get a quick preview of the verdict, if there was any doubt about whether the film would be passed for exhibition, without having to edit the film, insert Danish inter-titles and submit posters and promotional images, all of which also had to be approved by the censor. This arrangement, which according to the newspaper Politiken (25 April 1926) had been “gradually” introduced, simplified the censorship process and thus benefited the film industry. But the same arrangement also implied hidden advantages for the censors, of which more below.

Dawn tells the story of the British nurse Edith Cavell, who worked in a Red Cross hospital in German-occupied Brussels during the First World War, and helped Allied soldiers and prisoners of war to flee their German captors. Cavell was betrayed, arrested, condemned by a German military tribunal and in October 1915 she was executed for her extensive and well-organised ‘conveying troops to the enemy’. The case attracted international attention and outrage even before Cavell’s execution, which quickly made her a martyr-figure. Today, a statue of Edith Cavell stands in St Martin’s Place, near Trafalgar Square in London. On the base of the statue is engraved:

Edith Cavell

Brussels

Dawn

October 12

1915

In this way, it is not only Cavell’s martyrdom that is immortalised on the monument, but also the title of the film, Dawn. The film is in no sense anti-German; it is, rather, a humanist anti-war film, and is at pains to lay the blame for the barbarism of the First World War on the ‘War Machine’, as the inter-titles repeatedly call it. Beautifully played by Sybil Thorndike, Edith Cavell is portrayed as a stoic and compassionate figure who undertakes her first act of rescue because she knows the family of the escaped Belgian soldier in question. She then begins to assist Belgian, French and British soldiers in a more systematic way. The German commander discovers that escaped prisoners are returning to battle and therefore has sound military grounds to investigate their path to freedom. And when a German officer catches Cavell red-handed, he is overwhelmed with empathy and neglects to inform his superior. In the end, it is a captured escapee who betrays his helper, Cavell, and she ends up before a German military tribunal and is condemned to death. None of the implicated Germans display any arrogance, joy nor triumphalism in the situation; they are only doing what the law and the wartime conditions require of them. And when Cavell is standing at the execution post, one of the infantry soldiers refuses to take aim or fire. She is executed, and in the British version of the film, there is a cut to her gravestone. The French audience got to see the execution itself.

The film’s presentation of Cavell’s story can be described as nuanced and more against war than anti-German, as the Danish censors concede in their assessment of the film in 1929. However, the film stirred up controversy even before its premiere in spring 1928. According to The Times, the German diplomatic delegation protested against the film’s exhibition in Britain on the basis that it would “disturb international relations”, that it depicted German officers “in a bad light” and that it was inaccurate in its reconstruction of the execution of Cavell. 4 This led the British Foreign Minister Austen Chamberlain to publicly condemn the film as “repugnant” in March 1928. Later, it was revealed in a detailed newspaper commentary that he had not actually seen the film before he opined on it. This indicates that the British Foreign ministry prioritised the relationship with Germany more highly than artistic freedom for a film about a national martyr — not unlike the Danish behaviour in relation to The People of the Borderland. The British Board of Film Censors denied the film a certificate. But the national Board only had an advisory role in relation to local censors, who were more positively inclined towards the film. So Dawn was indeed distributed to British cinemas, despite the German protests.

This British controversy over Dawn shows that the Danish Foreign Ministry’s docile attitude to Germany was not without parallel or precedent, when Schnedler-Sørensen tried to get the same film passed by the Danish censors a year later. Dawn had already been approved by the Norwegian censor’s office, but banned by the Swedish equivalent, which riled up the Swedish press as well as some Social Democratic politicians. In Denmark, where the version approved in Norway was the one submitted for pre-approval, there was “complete agreement amongst the censors that the film would be banned if it were submitted officially for censorship”. This was despite the admission that the film was well balanced and “neutral” in its depiction of the German military. As described previously, the German officers carry out their duties without enthusiasm when trying and executing Cavell; it is what the situation and the military system requires of them. But that, declared the Danish censors, would incline the audience to feel “unsympathetic, yes, even hostile towards the German conduct of the war and the spirit which defines it.” So Schnedler-Sørensen and Fotorama’s request was declined: “when this was unofficially communicated to Fotorama, the company agreed to quietly retract the film without requiring an official censor’s decision”, noted the Ministry of Justice. The same ministry had asked Schnedler-Sørensen to “take the advice on board without allowing the case to become a matter for discussion in the press”, which he accepted, and concluded: “In this way it can be asserted that in this country the film is not formally banned.” 5 In other words, the system of unofficial test-censorship could be used to create a smokescreen to conceal what the censors rejected and what they approved for exhibition. This renders the formal press releases about the relative numbers of approved, censored and banned films, which censor Nicolaisen in particular often issued, rather unreliable. And it also indicates that the Foreign Ministry and Ministry of Justice were at pains to conceal the political censorship in which they indulged.

In any case, it was not just complaints from German diplomats that the Danish Foreign Ministry had one eye on in its dealings with the censor’s office. Critical column inches by German correspondents in Copenhagen about Danish film censorship could inspire intervention by the ministry. In October 1927, the Danish Embassy in Berlin shared with the ministry some German reviews of King Vidor’s feature film about the First World War, The Big Parade. The context was that a German journalist in Copenhagen, Hermann Kiy, had directed “Strong attacks at the Danish film censor, because it had approved the film”, which now — albeit with some cuts — was running in German cinemas. In Germany it attracted positive reviews, which led the Press Attaché Larsen in Berlin to ask the Foreign Ministry in Copenhagen to meet with “Mr Kiy to make him understand that the German correspondents in Copenhagen seem to be better at taking offence than the German film authorities themselves.” 6

This example suggests that respect for the “German necessity” sometimes became a bit too pronounced for even the Danish diplomats. But the Foreign Ministry’s docility was nonetheless regularly given expression in what we would today regard as trivialities. This can be seen from several interventions by the Press Office:

Two years before the saga of The People of the Borderland, in December 1923, the Danish delegation in Berlin warned the Foreign Ministry that the film Adlerauge (Eagle Eye, director unknown) had been banned in Czechoslovakia after protests from the German ambassador in Prague. The controversy was ignited by complaints of anti-German content. 7 The film was not in Danish cinemas at the time, only a title that “someone may seek to show in Denmark”. Nevertheless, the Foreign Ministry asked the embassy in Prague to get hold of the screenplay and have it translated and sent to Copenhagen in January, because “it is often the case that a propaganda film of that kind switches its title and is edited, in order to gain favour with the censor.”8 Thus it was seen as crucial that the film would be recognised regardless of the guise in which it might arrive in Denmark; the diplomatic missions in Berlin and Prague, as well as the Foreign Office and Ministry of Justice, were all put to work on preventative measures against “possible exhibition” of an American film that German diplomats in Prague didn’t care for.

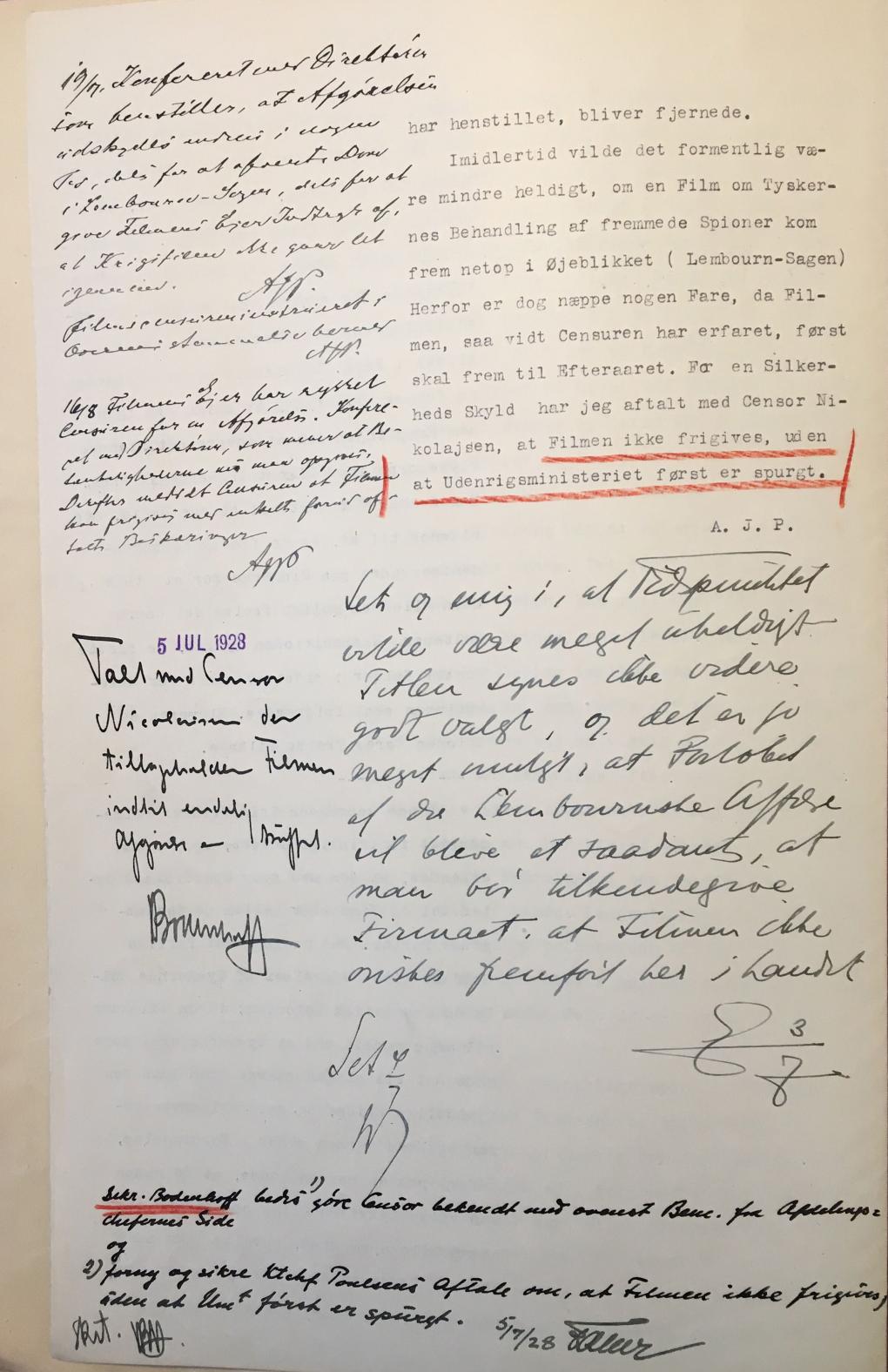

Attention was directed to an equally trivial case in 1928, when the American spy film The Legion of the Condemned (dir. William A. Wellman) appeared on the civil servants’ radar. The film itself was not seen as problematic by the Foreign Ministry; it was a balanced war film about French spies behind German lines, who are taken prisoner and condemned to death, but liberated at the eleventh hour. But although the film “with a complete lack of bias divides up the sun and the wind equally between the two warring sides”, censor Nicolaisen agreed with the Foreign Ministry that the film would not be released for theatrical exhibition before the ministry had given permission. The context for postponing the film’s distribution was a contemporary Danish-German espionage case, the so-called Lembourn case. This concerned a young Danish captain, Harry Lembourn, who had been arrested during what the military historian Michael H. Clemmesen describes as a “week-long, crazily improvised recruitment and spying stint in Germany” (2019: 15). Lembourn was convicted of, inter alia, investigating whether German breaches of the Treaty of Versailles regarding remilitarisation were taking place. His intelligence was — without his knowledge — channeled to the French intelligence service. 9 The Foreign Ministry’s justification for blocking the release of The Legion of the Condemned was as follows: “At this moment it would probably be unfortunate if a film about the Germans’ treatment of foreign spies emerged (Lembourn case)”. Below and in the margins of the typewritten document, more than one civil servant has added their handwritten opinion, including the comment that “it is quite possible that developments in the Lembourn case will mean that we must inform the company that it is not desirable for the film to be shown in this country”. In the margin, another seconds this with the detail that the writer has “spoken with Nicolaisen, who will block the film’s release until this is resolved”. The documents show that the aftermath of an ongoing spy case could, according to the Foreign Ministry, justify postponing the release of an American spy film, and perhaps even banning it altogether — in Denmark, anno 1928.

The polemic about The People of the Borderlands, and the various sagas concerning the screening in Denmark of foreign films with a First World War theme, lead us to several conclusions. Firstly, while it is established fact that cinema and film censorship fell under the domain of the Ministry of Justice in 1920s Denmark, this is a truth in need of some modifications. The respective influence of the Foreign Ministry and of foreign diplomats made itself felt in regard to the exhibition of Danish and foreign films alike. Furthermore, it is obvious that there was politically-motivated censorship. This was not just a matter of taking the scissors to anything that was “crude or in any other way morally damaging…anything that can inspire criminality, is blasphemous, or immoral”, as Nicolaisen summarised the main principles of censorship underlying his own work and that of his fellow censors in an extended interview in Politiken of 25 April 1926. In the same interview, Nicolaisen recounts — contradicting himself somewhat — that a Russian “Bolshevik film” has been banned on account of its “tendencies”. He thus admits that political censorship was also exercised by the film censors without ministerial encouragement. This was the same Nicolaisen who had answered with a categorical ‘no’ when asked, the year before the People of the Borderlands controversy, if there was political film censorship in Denmark — this time in the context of the censorship of a film showing Mussolini enjoying the adoration of his Italian followers (Sandfeld 1966: 469). That denial sounds all the less convincing in light of what we now know about The People of the Borderlands, the American and British films discussed above, and several more — in all these cases, what mattered was not damaging the relationship between Denmark and Germany.

The censorship of The People of the Borderlands grew into an acute national-political controversy and had international impacts, too: the discussion in the British press and the involvement of the German diplomatic mission. This case, as well as what we have seen of the censorship of controversial foreign films, has implications for our understanding of the common Danish-German film culture which the research group behind this theme issue are investigating. It did exist, but was very asymmetrical in its balance of power. German protests influenced what could be shown in Danish cinemas. The events surrounding the ban of The People of the Borderland show that in 1925 there were clear, nationally determined limits to which themes a film could explore; a particularly sensitive subject was the border region between Denmark and Germany. All the more so if the narrative tackled the First World War, a subject which could also embroil foreign films in diplomatic skirmishes and political censorship. And this was just as true earlier in the decade, for example in 1923, when even a possible release in Denmark of the American film Eagle Eye inspired pre-emptive action. It is hard to imagine how the Danish authorities could have behaved more cautiously.

The role of the Foreign Ministry on the ‘film front’ can be understood as inevitable, in the sense that taking account of foreign relations has always had a part to play in most forms of censorship. And it was here, in the Foreign Ministry, that German protests about film in Denmark took root and burgeoned into diplomatic crises. Moreover, on several occasions, it was the Danish embassy in Berlin that warned the Foreign Office when a controversy was about to ignite. In such contexts, political censorship seeped downwards from the Foreign Ministry, via the Ministry of Justice, and into the film censors’ office. The role of the Ministry of Justice in the 1920s seems to have been less politically proactive; essentially just the organ which administrated film censorship and the system of film-related grants. This changed considerably during the 1930s and the Occupation years (1940-45), when the ministry’s film tsar, Vilhelm Boas, consolidated the political censorship function of which the Foreign Office had been the primary exponent in the 1920s (Sørensen 2014). However, the activism of the latter grew out of a film-political context as well as from foreign policy concerns. It was the Foreign Office that was the first Danish public institution to commission film productions: in 1920, it had a series of films made about Denmark, with the purpose of promoting the nation abroad (Nørrested & Alsted 1987: 15). So it is true enough that the Foreign Office kept a tight grip on what could be screened in Denmark in the 1920s, but it is also the case that it was an innovator in its goal-oriented investment in film. This paved the way for later state institutions like Dansk Kulturfilm, Statens Filmcentral (the State Film Centre) and Ministeriernes Filmudvalg (the Danish Government Film Committee), which all played important roles in the development of Danish documentary in particular.

Notes

1. Rigsarkivet (RA, National Archives) 0002 Udenrigsministeriet (UM) 1909-1945, Gruppeordnede sager 115, A6-A31, 115-2.

2. RA 0002 UM 1909-1945, Gruppeordnede sager 115, A6-A31, 115-2.

3. According to an article in the newspaper Søndags-B.T. dated 9 September 1928, the censor forbade the production of a stage play about the Dreyfuss affair on the basis of a secret diktat from the Foreign Office, in response to pressure from the French Embassy.

4. https://greatwarfiction.wordpress.com/2015/10/26/dawn-edith-cavell-and-the-censors/

5. RA 0002 UM, 1909-1945, Gruppeordnede sager, 115 C.-D.5.1, 115-7

6. RA 0002 UM, 1909-1945, Gruppeordnede sager, 115 A.47-A.8, 115-6

7. RA 0002 UM, 1909-1945, Gruppeordnede sager, 115 A.6-A.31, 115-2

8. RA 0002 UM, 1909-1945, Gruppeordnede sager, 115 A.6-A.31, 115-2

9. http://blog.clemmesen.org/2018/04/03/the-current-understanding-from-the-reading-of-the-lembourn-sources-after-first-additions-from-the-family/

References

Clemmesen, Michael H. (2019) Sønderjyllands forsvar og Lembourns spionage, Odense Syddansk Universitetsforlag.

Nørrested, C. & Alsted, C. (1987) Kortfilmen og Staten. København, Forlaget Eventus.

Sandfeld, Gunnar (1966) Den stumme Scene. Dansk biografteater indtil lydfilmens gennembrud. København, Nyt Nordisk Forlag.

Skands, Laurids (1925) ‘Grænsefolket’. Manuscript Collection, Danish Film Institute Library.

Sørensen, Lars-M. (2014) Dansk film under nazismen. København, Lindhardt og Ringhof.

Suggested citation

Sørensen, Lars-Martin Sørensen (2021), The People of the Borderland – A forbidden film, a powerful neighbour, and film censorship as foreign policy. Kosmorama (www.kosmorama.org).

Watch the fragment of the film at Stumfilm.dk: