|

Western art is a cinema of sex and dreaming. Camille Paglia |

Antichrist (2009) opens with two signboards: “Lars von Trier” posts the first one and then the second: “Antichrist” – as if suggesting that Trier and Antichrist might be the same person. Trier’s name (as well as the words in the chapter signs that are displayed throughout the film) looks as if hastily written with chalk on a blackboard after something else was erased, suggesting it has only a temporary status.

What we notice about the title design is that the word “Antichrist” (painted in red letters on a green background: the complementary colours suggest opposite elements), with its enigmatic religious and cultural associations as an incarnation of Satan, is spelled in a peculiar way. The last T, resembling a cross, is transformed into the old Venus sign traditionally understood as the representation of a hand mirror, symbolizing female vanity. By contrast, the male counterpart, the Mars sign, is symbolically associated with a spear and a shield. This indicates that the Satanic Antichrist somehow can be identified as a woman: Satan as Venus, Venus as Satan.

The designer of the signboards is Per Kirkeby, the most renowned contemporary Danish painter who also contributed designs for Breaking the Waves (1996) and Dancer in the Dark (2000). The idea, however, of using the Venus sign, indicating the demonic power of women, was in fact Trier’s own. 1 With the design of the title, used as an icon for promoting the film, we are – from the beginning – drawn into the theme and the provocation of the film: The woman as the root of all evils.

When it premiered at the 2009 Cannes Film Festival, the film became a major topic of conversation due to its disturbing and violent plot elements, and controversial perspective on the woman. The film, affirming Trier’s position as one of the most innovative and controversial contemporary filmmakers, was accompanied by a statement where the director explained that his work was the result of a mental depression. He talked about his “Inferno Crisis” and explained that the images of the film “were composed free of logic or dramatic thinking.” He also said that Antichrist was “the most important film of my entire career.” 2

There are many possible perspectives on Antichrist – the horror element, borrowing from Japanese J-Horror; the shamanist element with talking animals; the religious elements of an anti-Eden; and the psychological elements with the mocking of cognitive therapy.

Here I shall focus on how the film uses the theme of sexuality and connects to European fin-de-siècle misogyny and dominating culture icons such as Nietzsche, Strindberg, Ibsen, Freud, and Munch.

The Prologue

Warning: Video with explicit content! The Prologue from 'Antichrist' (Lars von Trier, Zentropa 2009).

The first scene of the film, The Prologue, which together with the epilogue create a frame around the story, is the nucleus from which the whole film can be said to be unfolded. These 5 minutes and 41 seconds of cinema is what the remaining 98 minutes investigate and interpret. It is also the logical starting point for an analysis of the film.

With its 43 shots, the sequence stands out with its striking formalistic aesthetical elements, which signify that the prologue has a special status. The use of black and white, contrary to colour in the rest of the film (except the epilogue), implies that the events happen on a different layer of narration. The use of high speed (super slow motion) creates intensified beauty and an original visual appeal. These cinematic devices also imply that the events we see transcend ordinary concepts of time. The use of montage gives a special atmosphere of artificiality and an awareness of an implicit authority that presents the narration for us and know what is happening in the two parallel events, the couple making love and the little boy getting out of his crib. The narration follows along with cross-cutting, the parents and their child. The restricted narration points out details, including details that none of the characters are aware of – like the baby alarm and the washing machine. The culmination of the intercourse matches the boy’s fall from the open window into his death.

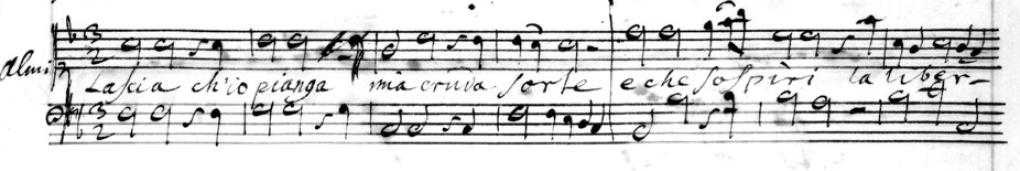

As there is no realistic sound, no dialogue or sounds, the music – classical music – receives maximum attention, creating a solemn meta-layer of synesthetic effect where music and picture melt together, reciprocally exchanging meaning. The baby alarm is on mute. But one could say that the entire sequence is on mute, all actual sounds are omitted to allow us to hear the music at full amplitude. The aria from Handel’s opera Rinaldo, “Lascia ch’io pianga mia cruda sorte” (“Let me weep over my cruel fate”), is elegiac and sad, expressing sorrow and despair in terms of clarified beauty. Handel’s opera, composed for the London stage in 1711 (with libretto in Italian) is loosely based on Torquato Tasso’s epic poem La Gerusalemme Liberata (The Liberation of Jerusalem), about the first crusade. The aria is sung by the knight Rinaldo’s love interest, Almirena, who has been abducted by a queen with witchlike powers. The female suffering in the music and text seems to parallel the suffering of the woman in the film, but when the music comes back in the epilogue, it gets an ironical character.

There is a significant tendency in modern cinema to use classical music as a symbolic ingredient that adds a special spiritual quality to a scene. In the 1960s and 70s, Kubrick, Visconti, Tarkovsky and Bergman were pioneers in this field. It continued in modern films like Se7en (1995), Children of Men (2006), Shame (2011), Biutiful (2010), and The Tree of Life (2011) where classical music delivers a certain atmosphere of grandeur, lifting the film to be a statement about existence and destiny. It is the same method Trier uses in his later work, where classical music adds a higher meaning, an Olympian perspective to the story, beginning with the use of Vivaldi, Handel, Albinoni, and Pergolesi in Dogville (2003) and Manderlay (2005); Wagner in Melancholia (2011) and César Franck and Bach in Nymphomaniac (2013, the same Bach organ piece that Tarkovsky used in Solaris (2002)).

In Antichrist, the Handel music seems to create a complex meaning and philosophical dimension by merging intense hypnotic imagery with profound music. It also seems to give the situation a more symbolic meaning. Through the music, the scene’s everyday situation – a married couple having sex – assumes a character of sacred, mythological ritual, interpreting the sexual pleasure into suffering and pain, somehow underlining the sadomasochistic character of the sexual enjoyment.

Altogether these formal elements add a symbolic layer to the prologue, removing it from the rather concrete realistic situation. The bathroom, the ventilator, the washing machine, the scales, the jigsaw puzzle, the playpen, the toys – all these ordinary props are swept into the aesthetical discourse, made hypnotic and ambiguous by the stylistic features of high-speed cinematography, precisely calculated montage, black and white and the intense classical music. They are transformed into a parable of human existence in general and of sexuality in particular.

In terms of narration, it is striking that the sequence is filled with dramaturgical omens and warnings as well as anticipations that we shall understand only in retrospect as the film continues. Under the boy’s playpen we see that his shoes are standing in the wrong position, the left to the right and vice versa (a theme that will later be very important to the plot); on the desk are three mysterious metal figurines (with titles: Grief, Pain, Despair – matching three of the chapter titles) and also a notebook (signifying academic studies);

the bottle turned over gulping its water out can be seen as a symbol of waste (a theme that will be important later in the acorn sequence), but also a metaphor of ejaculation; the teddy bear is floating in the air (tied to a balloon) seemingly able to fly (suggesting that the accident could be explained as the result of the boy wanting the teddy bear to enjoy the snowy weather and also himself to fly like the bear).

We notice, however, that one important theme seems rather absent in the scene: We are in Seattle, on the third floor in an apartment complex on a street with parked cars. There are no trees, grass, flowers and no live animals in the house. There are no signs of the natural environment that will later be a significant part of the film. Nature is not introduced until the hospital scene where the omniscient camera tracks in very close to the rotting stems in the vase. This signifies in a demonstrative way that there is something dark and threatening in nature that we should look out for. It is only a small detail but it will later expand and fill the entire setting of the film, much like the classical technique in William Archer’s Play-Making: “one of the keenest forms of theatrical enjoyment is that of seeing the curtain go up on a picture of perfect tranquility, wondering from what quarter the drama is going to arise, and then watching it gather on the horizon like a cloud no bigger than a man's hand.” 3

But the nature theme is suggested, indirectly and implicitly, in the prologue: there is the teddy bear and there is also the jigsaw puzzle (a very simple one with only three pieces each with a pin as it is used by small children), lying on a cupboard in the bathroom and disturbed by the lovemaking of the parents. It shows the three animals that will be major agents in the story – the deer, the fox, and the crow (the fox piece jumps up when the woman’s buttock touches it during sex, signalling a connection: later in the film the demonic fox jumps up when the man touches it).

For much of the running time of the film, the development of the story seems to confirm that this is a story about grief therapy and about coming to terms with the loss of a child in a tragic accident. It also appears to be a story about the brutality of nature, portrayed as a demonic environment. It is only towards the ending of the film that we realize that this was a kind of misdirection. Somehow the central, determining factor was sexuality, more precisely female sexuality. After all, the starting point of the story is a scene of sexual intercourse.

Sexuality in Trier’s work

Sexuality goes as a dangerously short-circuiting wire through Trier’s entire oeuvre. Male sexuality, when it gets any attention at all, is described as a rather simple thing – like in the funny, 48 seconds, commercial Sauna (1986), made for the Copenhagen tabloid newspaper Ekstra Bladet: The camera surveys a men’s sauna where a young man discovers a tiny opening with wire gauze on the wall, allowing him to peer into the women’s sauna. On the other side, the strict matron notices the eyes behind the gauze and angrily lines up all the men to find the culprit. He stands there, looking shameful, hiding his erected limb under a newspaper. The catch line says: “What would we do without Ekstra Bladet?” Here we get Trier’s judgement on male sexuality: no death and no demonic fall into darkness – just desire, with a voyeuristic angle.

Female sexuality, however, is presented as an area of endless mystery and alluring perdition. In Trier’s films prior to Antichrist, women are generally portrayed in two ways: they are either unreliable, deceitful or directly evil; or they are good and self-sacrificing, mirroring the traditional Freudian stereotypes of Whore and Madonna. But in any case, their sexuality is an area of mysticism.

In the short The Orchid Gardener (1977) and Menthe la Bienheureuse (1979), made as private productions by Trier during his university years, there are female characters of a rather enigmatic and threatening sexuality. Esther in the Film School graduation film Liberation Pictures (1982) lures her lover, the German soldier, out into the forest, where he is seized and tortured to death by partisans. The prostitute Kim, in Trier’s feature debut The Element of Crime (1984), is seen by the male protagonist as a traitor, secretly in contact with the elusive Harry Grey; Katharina in Europa (1991) uses her husband as the naïve instrument in her conspiracy together with the Nazi Werewolves. All of these women contribute to their male counterpart’s downfall, as does the titular character in Medea (1988). Additionally, Judith, the young woman who is the girlfriend of a doctor called Hook in The Kingdom (1995/97), has some doubtful features – she is pregnant by a satanic ghost and gives birth to a monster baby (in The Kingdom II).

By the mid-90s, Trier’s female figures underwent a sudden transformation and became self-sacrificing and good. Evidently, it was this character metamorphosis that spurred his international breakthrough. When the tormented idealist male protagonists of the early films were replaced with emotionally dedicated women, often of a rather naïve simplicity, his films surpassed the limitations of art film and acquired a much more mainstream-like appeal even though they kept the experimental art film elements intact.

Apart from the less successful comedy The Boss of It All (2006), all of Trier’s films since Breaking the Waves (and until The House That Jack Built (2018)) have a female protagonist. Bess in Breaking the Waves lets herself be sexually humiliated in an attempt to rescue her incapacitated husband. Selma in Dancer in the Dark also sacrifices herself (though not for a partner but for her young son). These films together with The Idiots (1998), about a woman coming to terms with her grief after the death of her infant child, constitute the so-called Golden Heart Trilogy. They are about unsuspicious and self-sacrificing women (inspired by a colouring book from Trier’s childhood about a little girl who gives away everything including her clothes to help other people). 4

Grace in Dogville can be seen as a combination of the two types of women: throughout most of the film, she is the self-sacrificing victim who patiently endures the physical and sexual abuse from the village people. However, in the end, Grace’s gangster father convinces her to put her vengeful fury into action and she orders them all to be killed. Since Antichrist, strong female characters and female sexuality are continuously present, both in Melancholia and especially in Nymphomaniac, which presents “the erotic life of a woman from the age of zero to the age of 50”. 5

The women in Trier’s films generally share bad luck in their personal relations with a partner. Bess in Breaking the Waves experiences great love, but after Jan is invalidated she must to give herself to men she has no feelings for. In Dancer in the Dark, Selma ignores the man who is interested in her. Dogville’s Grace is abused by the men and her relationship with Tom results in his execution along with the rest of the villagers. Justine in Melancholia refuses the personal relation, distancing herself from her bridegroom. She is only able to surrender herself to the cold light from the approaching threatening planet. And Nymphomaniac, by virtue of its title, announces another woman with alienated relations. 6

The Woman in Antichrist

The nameless ‘She’ of Antichrist starts as a grieving, suffering woman, calling for our empathy but gradually, her behaviour becomes increasingly aggressive and violent. But who is She? She has no personal profile and only a limited past history shown in the film (the only flashback is of her working on a dissertation). She is nameless and lacks identity beyond her sexuality. Implicitly, she signifies a woman who, more or less, can be reduced to a sexual being. The challenge is not only that her sexuality represents a connection to dark, uncontrollable forces, but also that she lacks distinct personal features beyond her sexuality. But it should also be noticed that the same goes for the man: “He” is also nameless, lacking individuality.

The prologue shows the couple making love in mutual passion. They seem to be equally engulfed in the act, even though the narrative has more focus on her passion. The expression of sexual pleasure on her face points to sexuality as the final cause of the drama, but we don’t realize that until much later. Her passion doesn’t appear demonical in any way, but that is because the scene omits some elements only to be revealed later. The terrible accident follows along with her uncontrollable grief. In his part, “He” is more detached and controlled. He will remain so for the rest of the film. His passion dissipates. She faints at the funeral and subsequently sinks into a deep depression. After the couple returns home, she awakes him from his sleep: “It resembles a rape attempt. She is uncontrolled and throws herself upon him,” it says in the manuscript. 7

He tries to ward off her approaches by referring to the relevant rule for professional behaviour: “Never screw your therapist” and manages to avoid intercourse. Though he adds: “… however much the therapist may like it”, we are not certain whether professional principles or lack of sexual appetite is the reason. In a later scene, she kisses him, playfully, but suddenly bites his nipple to bleeding, 8 implicitly announcing that her sexuality involves aggression, as it will be more and more obvious. In the cabin they embrace during the night. 9 After he has tried to explain and analyse her behaviour for her, she suddenly hits him, “beats him as hard as she can” 10 and “they tumble around on the floor.” 11 And later: “They are making love again. She is completely abandoned, but his heart is not really in it.” She wants him to hit her “so it hurts!” 12 After he doesn’t give her what she wants, she runs out into the woods. He follows, only to finds her masturbating. 13

They have intercourse at the root of the big tree. This is the iconic still picture from the film: “Handheld tracking toward his neck as he is screwing her. (…) Behind the network of roots in the earth, human bodies grow out on both sides of the couple: naked, dead, wracked bodies!” 14 (It should be noted, though, that the film doesn’t follow the script entirely: we don’t see the bodies grow out; they are motionless). Here carnal pleasure, nature and death are united in a disturbing synthesis.

Next day, back in the cabin, she discovers the autopsy report in the waste paper basket and is confronted with his suspicion that she deliberately maltreated Nic’s feet. He goes to the workshop, which she enters and attacks him sexually. During intercourse she suddenly knocks him out, then “crawls over and straddles him, jerking him off until he climaxes in big squirts of blood spattering over her.” 15 Later, after her gruesome acts against him – including her ‘penetration’ of his leg with a hand drill – there is a sex scene where she uses his hand to masturbate herself and she has a vision, a flashback to the prologue scene – “her recollection of the film’s first sexual intercourse in the apartment.” 16

We now see that she actually did see Nic. She noticed what was about to happen but didn’t interfere: “She looks in silence at the boy crawling toward the abyss. Her eyes never leave him and she seems totally indifferent to his situation. (…) She stares coldly at the boy falling out of the window, before she once again shuts her eyes and abandons herself to sexual ecstasy.” 17 Seemingly as a consequence of her realization of what happened, identifying her evil towards Nic as originating in her sexual lust, she performs clitorectomy on herself, destroying the source of sexual pleasure that led her to sacrifice the child.

The sexuality in ‘She’ is presented as a kind of madness, an obsession matching, one could say, with Beauvoir’s view: “Feminine sexual excitement can reach an intensity unknown to man. Male sex excitement is keen but localized, and – except perhaps at the moment of orgasm – it leaves the man quite in possession of himself. Woman on the contrary, really loses her mind.” 18 They came to the same conclusion in the Antiquity: 19 “Who doubts the truth? The female’s pleasure is a great delight, much greater than the pleasure of a male.”

‘She’ is clearly a controversial representative of womanhood. That her evil has roots in her sexuality is a challenge to the usual stereotypes of female behaviour. Throughout the film, the sexual initiatives come from her, marking her different states of mind.

She is a woman who has a difficulty of bonding and caring for people. She fears that the husband will leave her and also discover her latent evil.

Freud’s Urszene

Several critics find that the prologue can be understood with reference to the Freudian concept of Urszene, the Primal Scene that Sigmund Freud (1856-1939) considered an essential element in the neurotic mind and supposedly in all minds:

Among the store of unconsciousness phantasies of all neurotics and probably of all human beings, there is one which is seldom absent and which can be disclosed by analysis: this is the phantasy of watching sexual intercourse between the parents. 20

Antje Flemming, Peter Priskil, Lilian Munk Rösing, Torben Grodal, and Christian Braad Thomsen have all discussed the scene as an example of this. 21 In the manuscript, the situation is described as an obvious Urszene: “Full shot of the two screwing and the child watching them silently in the foreground, the teddy bear in his arms.” 22 Also, in the storyboards drawn for this scene, the boy observes his parents making love. However, it differs from the final film.

Though the prologue shows Nic passing by the room where the parents are making love on the bed (they have moved from the bathroom to the bedroom, a transition that is not shown), it is not obvious that he actually sees them. He just turns his head with a strange, ambiguous expression looking at the teddy bear and the window. Nothing in his face or movements signifies that he has actually noticed the parents, nor that he is scared or disturbed by what he might be seeing. There is no marking of a trauma being created in his mind. On the contrary, his expression is one of curiosity looking at the snow (most likely it is the first snow he has ever been aware of in his short life: he is two years old [the actor was two and a half at the time of the shooting]). It should also be noticed that the lovemaking at this point isn’t shown in a way that could be seen as particularly aggressive or scary. And Trier has later explained about Nic: “It doesn’t interest him that Dad and Mom are having sex.” 23

For Freud, the small child watching his parents make love was an experience that could pervert the child’s attitude to sexuality later in life. But in Antichrist the incident is not about how the boy perceives it, but about how the mother perceives it. Maybe that is why it was changed from the original plan.

Antichrist and pornography

One of the first shots in Antichrist (shot number seven in the prologue) is a close-up of hardcore copulation, allegedly performed not by actors Gainsbourg and Dafoe, but by two German adult film performers, Horst Stramka (also known as Horst Baron) and Mandy Starship (whose identity remains unconfirmed), hired as body doubles for this special shot (and the later shot of the penis that ejaculates blood). Trier explained that he had to use a stand-in penis for Dafoe: “Yes, yes, we had to have, because Will’s own was too big.” 24

The shock of the effect is surprising. There is, after all, an enormous industry that tirelessly produces hard-core pornography filled with penetration shots, quite visible in the digital media landscape. But we are surprised because we don’t expect to see the two parallel media industries (possibly of equal size economically) cross each other. 25 “What I’m doing is I’m actually mixing up the genres a little bit here, so that we put full penetration into a film where full penetration should not be,” Trier said, 26 always eager to contradict conventional behaviour and ignore taboos.

The penetration shot can be seen as a warning that the film, despite the immediate signal of an art film (black and white, high speed, with classical music), will offer daring and provoking elements. When a veritable penetration shot appears in an unmistakable art film, we experience it as a deliberate collision between high culture and popular culture, an effect that Trier always has favoured.

In the 70s, when Trier was a young man, a wave of films with focus on sexuality appeared, not only notorious porn flicks like Deep Throat and Behind the Green Door (both 1972), but also mainstream films like John Schlesinger’s Midnight Cowboy (1969), Mike Nichols’s Carnal Knowledge (1971), and Sam Peckinpah’s Straw Dogs (1971) as well as art films like Bernardo Bertolucci’s Last Tango in Paris (1972), Nicolas Roeg’s Don’t Look Now (1973), Liliana Cavani’s The Night Porter (1974), and Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Salò (1975). These films provoked audiences with their explicit sexual situations, though an unwritten law seemed to deem an authentic shot of penetration to be too vulgar, too direct, and too awkward for the actors, undoubtedly, to go all the way. But that border was momentarily crossed in Nagisa Oshima’s Japanese In the Realm of the Senses (1976), according to Linda Williams, the first successful combination of hard-core sex and art film. 27

Art films with a very explicit sexual content had new energy in a second wave in the late 1990s, beginning with Trier’s own The Idiots (1998), where adult performers were hired for hard core penetration shots seen in a few seconds, followed by films of more or less explicitness such as Catherine Breillat’s Romance (1999) and À ma soeur! (2001, Fat Girl), Patrice Chéreau’s Intimacy (2001), Michael Winterbottom’s 9 Songs (2004), and John Cameron Mitchell’s Shortbus (2006), as well as Alfonso Cuarón’s Y Tu Mamá También (And Your Mom Too, 2001), Bernardo Bertolucci’s The Dreamers (2003), and Ang Lee’s Se, jie (2007, Lust, Caution).

Antichrist continues this trend, exploiting, more radically than any of the other films, the clash between two traditionally incompatible media universes. Trier’s work provocatively mixes adult film tropes with the art film. Antichrist refers to the pornographic film in much the same way it refers to the horror film, effective since the film brings the two genres in connection with each other. (A project that Triers brings to a new a height in Nymphomaniac). 28

The typical heterosexual adult film will show the sexual actions from a male point of view (and with the male audience in mind). One of the basic stereotypes in adult films, probably mostly a projection of wishful male fantasies, is the submissive woman who obediently and compliantly responds to the man’s initiative. In mainstream pornography the culmination is not her fulfilment, which typically remains diffuse, but invariably the ‘cum shot,’ showing the man’s ejaculation as the visible proof of his orgasm. This is what it all is about. Cf. Linda Williams:

To the degree that pornography has been articulated from an exclusively male point of view, it is not surprising that the hard-core fetish par excellence has been the “money shot”. But we have also seen that this particular “erotic organization of visibility” cannot satisfy the genre’s increasing curiosity to see and know the woman’s pleasure. 29

Antichrist, however, has a different orientation. The ‘She’ of Antichrist is the aggressively insatiable woman, who again and again attacks the man with her spontaneous sexual desires, as a kind of scary parody of the all-too-willing woman. She is not presented as promiscuous (only one man is available), but her sexuality is shown as an obsession that clearly is not about sharing intimacy and passion with the partner but rather an experience for herself. This signifies a solitary passion where He is a suitable instrument, actually rather a reversed parallel to mainstream pornography where the woman typically is an instrument for male fulfilment.

But the story makes it explicit that the craving for sexual fulfilment is also a journey into darkness and death. In the prologue, sexuality and death are symbolically combined. Her orgasm interacts with the falling of the boy.

From the man’s eyes looking upwards to the woman’s eyes looking upwards. As the boy is falling to his death, she is reaching the culmination of orgasm, implicitly comparing Nic’s death with her own “petite mort”, the French metaphor of orgasm. And in the end, she first punishes herself by cutting off her clitoris; then, when that evidently isn’t enough, seems to accept as the only solution that the husband kill her. First, he refuses, but later he yields to her wish and slaps her. She wants punishment. She fights against him, but she also finally seems to accept punishment and even death by strangling.

Her sexuality is presented as related to aggressiveness and death much in the same way as Sontag sees sexuality in her famous piece on pornography:

Tamed as it may be, sexuality remains one of the demonic forces in human consciousness - pushing us at intervals close to taboo and dangerous desires, which range from the impulse to commit sudden arbitrary violence upon another person to the voluptuous yearning for the extinction of one’s consciousness, for death itself. 30

In the Antichrist script her death is similarly described:

He squeezes again and for a moment she loses consciousness. Then he loosens his grip and she comes to. She looks sadly at him, as if to say, ‘Don’t give up so easily ... you’re doing well!” He looks at her and is seized by doubt. She smiles at him to signify that it is okay. She looks for a long time at him while his grip is loosened, smiling to him with love and encouragement. 31

‘She’ is related to the sadomasochistic characters in regular porno films like The Story of Joanna (1975) and The Punishment of Anne (1975) and in art films like Oshima’s In the Realm of the Senses. These women can be seen as “Female Victim-Hero(es)”, as characterized by Linda Williams, 32 as can She (in Antichrist) who is both a victim – the grieving mother – and an aggressive sadomasochistic pleasure seeker, both “good” and “bad”:

The slasher film kills off the sexually active “bad girls,” treating them as the victim-heroines who cannot save themselves, and reserves heroic action to the sexually inactive “good girl” victim-hero. Sadomasochistic pornography, in contrast, combines the “good” and “bad” girl into one person. 33

In the erotic/pornographic genre there are films about female cruelty, female sadism and sadomasochism, where punishment and pleasure go together, connected to each other, typically in popular culture exploitation products like the Ilsa films (the first was Ilsa, She Wolf of the SS, 1975, dir. Don Edmonds).

In Antichrist the theme of abuse and torture in the forest is used again but here the ‘sadism’ is not turned against the woman but is done by the woman. ‘She’ is the victim and the executioner in one double-sided person. She is the evil temptress but also the victim realizing her demonic nature that unavoidably must lead to her own death and annihilation. Sexuality appears not as a positive life-confirming force, but as a demonic activity, as perversion. “It can’t be hidden that Trier’s portrayal of sensuality as a main principle is taken from the pain-excitements of sadomasochism” says Grodal, 34 who also had pointed out “a theme that is prominent in most of Trier’s films (…) the ambiguous coupling of sexuality (pleasure) and pain (suffering).” 35

Pleasure and punishment

Antichrist and later Nymphomaniac can be seen as heroic attempts to pull explicit and barrier-breaking sexuality away from the clutches of the adult industry. Sexuality is far too serious an issue to be left to the porn industry, one could say. But at the same time there is clearly a connection between pornography and Trier’s sexual universe. The link is: depersonalized, non-emotional sex.

When the adult industry delivers thousands of visualizations of depersonalized, non-emotional sex, it confirms clearly that there is an enormous (male) audience that finds pleasure in imagining depersonalized, non-emotional sex. It is also a fact that prostitution basically is a business that delivers depersonalized, non-emotional sex to male customers. This is no news.

When women suddenly are shown similarly to enjoy depersonalized, non-emotional sex, it becomes scary and perhaps also arousing. This is what we find in Trier’s work. In nearly all of his films, female characters take pleasure in depersonalized, non-emotional, detached sex, and even in suffering humiliation and violence, punishment and self-punishment. “Carnal lust and the loneliness of the soul” – the famous dictum from Dreyer’s Gertrud (1964), admired by Trier. 36

Sex in Trier’s work is generally without personal and emotional relations. In The Element of Crime, the protagonist announces to the woman that he will “fuck [her] back to the Stone Age”. In Breaking the Waves, Bess has come to believe, in a kind of agreement with God that her sexual humiliation with random men will redeem her disabled husband. In Dogville Grace, chained to a metal wheel, is abused by the village men; in Manderlay Grace has impersonal sex with Timothy (Isaac De Bancole) who puts a veil over her face). In Melancholia Justine deserts her husband on their wedding night, has sex with a random man and seems able to surrender herself fully only to the cold light from the threatening planet. In Nymphomaniac we follow a woman’s promiscuous life story, that includes an incident demonstratively referring to Antichrist’s prologue where the father now rescues their son about to fall from a balcony. 37 It is significant that Jack in The House That Jack Built is not shown having sex with the women, instead he kills them – the woman with the car trouble (Uma Thurman), the widow (Siobhan Fallon Hogan), the mother with the two young sons (Sofie Gråbøl), and the naïve Jacqueline (Riley Keough), the last two his lovers.

Sadomasochism and punishment are recurring themes in Trier’s work. Menthe la bienheureuse focus on pleasure and punishment, in The Element of Crime the jumpers volunteer in a painful ritual, in Europa the father chooses suicide. The sexual humiliation of Bess in Breaking the Waves can be seen as a punishment that she accepts in order to cure her husband. In Dancer in the Dark Selma accepts her punishment (capital punishment!) as self-sacrifice. In Dogville Grace punishes the entire village, but before that she has, for a surprisingly long time, accepted humiliation and abused by the men. In Manderlay, Grace has to personally execute the woman who stole bread from the children. And the whole concept of Dogme can be seen as a kind of artistic (self)punishment. To quote myself:

There is more than a touch of masochism in this approach to artmaking. This self- torture should be seen as a way to force mold-breaking results. The Dogme artist punishes himself in the ways that hurt the most, in the expectation that it will lead to artistic liberation. While most stick to convention and work within the established norms, von Trier forces himself to try out new ways of doing things. As early as Epidemic, he proclaimed, “a film should be like a pebble in your shoe.” In a manner of speaking, Dogme is institutionalized masochistic renunciation as a designated path to artistic development, asceticism as a path to blossoming. He has carried this over into his recent works, which are not Dogme films but follow other complex, inhibiting rules. 38

In The Five Obstructions (2003, co-directed with Jørgen Leth) Trier is in charge of giving the various assignments to Leth, but we notice that they often have the character of a punishment. Leth is again and again asked to do what he will hate to do. Implicitly he is thereby purified and ‘saved’ through a kind of torture similar to that used against witches and heretics in ancient times.

This motive of a person co-operating with its own punishment is also found in Trier’s Medea where the older boy not only helps the mother hang his younger brother but also accepts his own hanging. Medea was based on Carl Th. Dreyer’s unrealized script, but this scene is not in Dreyer’s script, it was Trier’s own invention.

However, Dreyer has a similar scene in Day of Wrath, his 1943 drama about witch hunt in the 1600s. At the ending of the film, the young woman, Anne, stands at the coffin of her husband, the old priest, when she realizes that her lover, the stepson, has betrayed her. When the mother-in-law accuses her of witchcraft, she doesn’t protest or defend herself, but accepts her fate and confesses:

Yes, I did murder you [the old husband] with the Evil One’s help … and with the Evil One’s help I have lured your son into my power. Now you know … 39

The Genesis of Antichrist

In October 2004, when Trier was editing Manderlay, the sequel to Dogville, producer Peter Aalbæk Jensen, then co-owner with Trier of Zentropa, announced that Trier’s next film would be a horror film called Antikrist:

As I understand it, Lars spins a yarn over the big lie that it was God who created the world. In fact, it is Satan himself.

And further information was:

The plot in “Antichrist” takes place around an anxiety therapist who gets a biologist in therapy who has become afraid of nature. It is evil, he thinks and seeks help with the therapist to get rid of his delusions – but is he actually right? That is the question in the film that still only exists in the Danish director’s head. 40

The project had started with the idea of Satan as creator of the world, of nature. Nature as an evil force. Trier has mentioned back in 1999 that he once saw an (unidentified) TV programme about the European primeval forests, where there is an immense brutality behind the beauty and the grandeur of nature:

I just saw a program about jungles, which was very interesting. If I try to imagine the most comforting image in the world, I see a forest lake with a bellowing stag, a waterfall in the background, and some mossy remnants of tree trunks. What’s amusing about precisely that image in relation to the jungle is that the latter involves an ongoing struggle for survival, whereas there’s hardly any struggle connected with the kind of forest we have here [in Denmark], because we know who the winners and losers are. It’s interesting that what we find most soothing is an image that points back to the worst thing of all. Had it been people instead of trees and animals, it would have been a Hieronymus Bosch image, humanity as a battlefield. 41

Trier, however, had not given his permission that the basic idea of Satan as the creator of the world should be made public and became very angry at Aalbæk and announced that the project was now cancelled.

He continued with other projects, resulting in the comedy The Boss of It All (2006), and after that, in autumn 2006, he went on with the 2004 plans about the psychiatrist Mary and her biologist patient Nicklas. It went on to become a story about Jeremy who had a childhood trauma when he lived in the forest with his father, a priest, and the little sister died. As an adult he is treated by a psychologist. On that basis screenwriter and director Anders Thomas Jensen wrote a new version of the script in which the menacing elements of nature were further developed. Trier believed Jensen’s more mainstream version would provide a better starting point for a financing of the project. It was never the plan that this draft should actually be used; it was not written for “creative reasons” 42 but conceived of as “a kind of dummy”. 43 In a short one-or-two days session, Trier described his material to Jensen, who then in ten days made a coherent script out of it.

It started with some ideas I had. Then I had the depression and could only mumble some words to Anders Thomas. (…) And then he wrote the whole story through. He made a manuscript so we could continue with the film. And then a read the manuscript and threw it all away. What he did was very important for the film. He thought it was a mess. 44

Starting in summer 2007 Trier made a new version of the script (Antichrist, second draft 26.1. 2008, 64 pp., in Danish) where the plot is radically changed, although it is actually a totally new script with only some elements in common with the first one. The story about a male patient, who is treated by a female psychiatrist, is made into a story about a female patient who is treated by a male therapist, who is also the husband of the patient. New is also the prologue with the lovemaking and the accident, the whole starting point of the plot. The narrative retains the elements of anxiety, horror, and therapy, but the childhood trauma motive (and all material about the father and his church) is nearly gone. The only trace of the childhood theme left in the final script is that She has been in Eden as a child, 45 but this was removed in the final film. Here the only childhood concerns Nic.

The other significant change is that the religious theme is marginalized, and that sexuality now has become the major theme of the film. In the earlier versions, sexuality is absent.

In the second draft, however, sexuality and controversial gender issues are in the centre, if not the centre of the story. It is now less realistic and appears (with the nameless characters) as an allegorical fable, a story about sexuality with religious themes in the background.

The second script was followed by a third version (Antichrist, 3. draft, 16.3. 2008, 72 pp. in Danish), now with more details and technical specifications. The Final script (in English, 72 pp.) is dated July 2008.

Antichrist and Early Trier

“Everything that I’m doing is based on stuff from way back. So no wonder that everything looks the same. It all comes from the same [sources],” 46 says Trier. And Antichrist represents in many ways a journey back to themes and ideas that can be found in some of his first products. The bottle ejecting its content in the Antichrist prologue recalls similar shots in his major film school films, Nocturne (1980) and Liberation Pictures (1982). The enchanted, demonized or allegorical forest echoes the final scene of Liberation Pictures, where the German soldier meets his destiny in the forest, has his eyes picked out and rises to Heaven over the treetops (similar to the crane shots in the forest in Antichrist). But it is particularly the sexual theme that connects to early Trier.

In Trier’s early work there is a clear absorption in perversity, marked by his interest in classic pornographic literature. Young Trier was fascinated by the Pauline Réage (real name: Anne Desclos) novel L’histoire d’O (1954, The Story of O), about a woman who takes masochistic pleasure from pain and promiscuous submission, and he admired de Sade’s Justine, the story of a young girl who again and again is abused by high-ranking men, as well as the sequel, Juliette, about the sister who enjoys perversion and kills her own new-borns.

His two early, privately produced films focus on sexual perversity: In Orchidégartneren (1978, The Orchid Gardener), the protagonist Victor Marse (played by Trier) is a paedophile molester/murderer who is seen with the body of a child, wears an SS-outfit and women’s clothes and also has a scene where the bare-breasted young woman prepares a whip with slime and salt for the distressed young man. Menthe la Bienheureuse (1979) was freely adapted from The Story of O with its sadomasochistic theme, and has a woman in chains and with a labia ring being whipped. Trier had as an early project a film based on Sacher-Masoch’s famous novel Venus im Pelz (1870, Venus in Furs) and wrote a detailed 50-pages manuscript, Verdande - af et oversanseligt menneskes bekendelser (Verdande - From the Confessions of an Over-Sensuous Human Being), but the film was never made. At the National Film School of Denmark, he made an assigned documentary, Dokumentarøvelse (Documentary Exercise), with paedophilia as its theme, a kind of Lolita-satire. He also made a script based on Marquis de Sade’s Philosophy in the Bedroom. “But Gert Fredholm, who taught direction, told me to destroy the script. It wasn’t enough that I couldn’t make the film. Any evidence that a script like that had been written at film school had to be destroyed! I made a short film based on a story by Boccaccio instead.” 47

In the 1980s, Trier had plans for a direct adaptation of Réage’s novel, and Justine was also Trier’s project for a number of years. 48 Later Manderlay, the second film of the US Trilogy, took inspiration from Jean Paulhan’s preface to The Story of O about the slaves who want to stay slaves, and it was the plan that Wasington (sic!), the last film of the Trilogy, would have the two actresses, Nicole Kidman and Bryce Dallas Howard, who played Grace in the two films, be sisters inspired by Sade’s Justine and Juliette characters. 49 But it was never made.

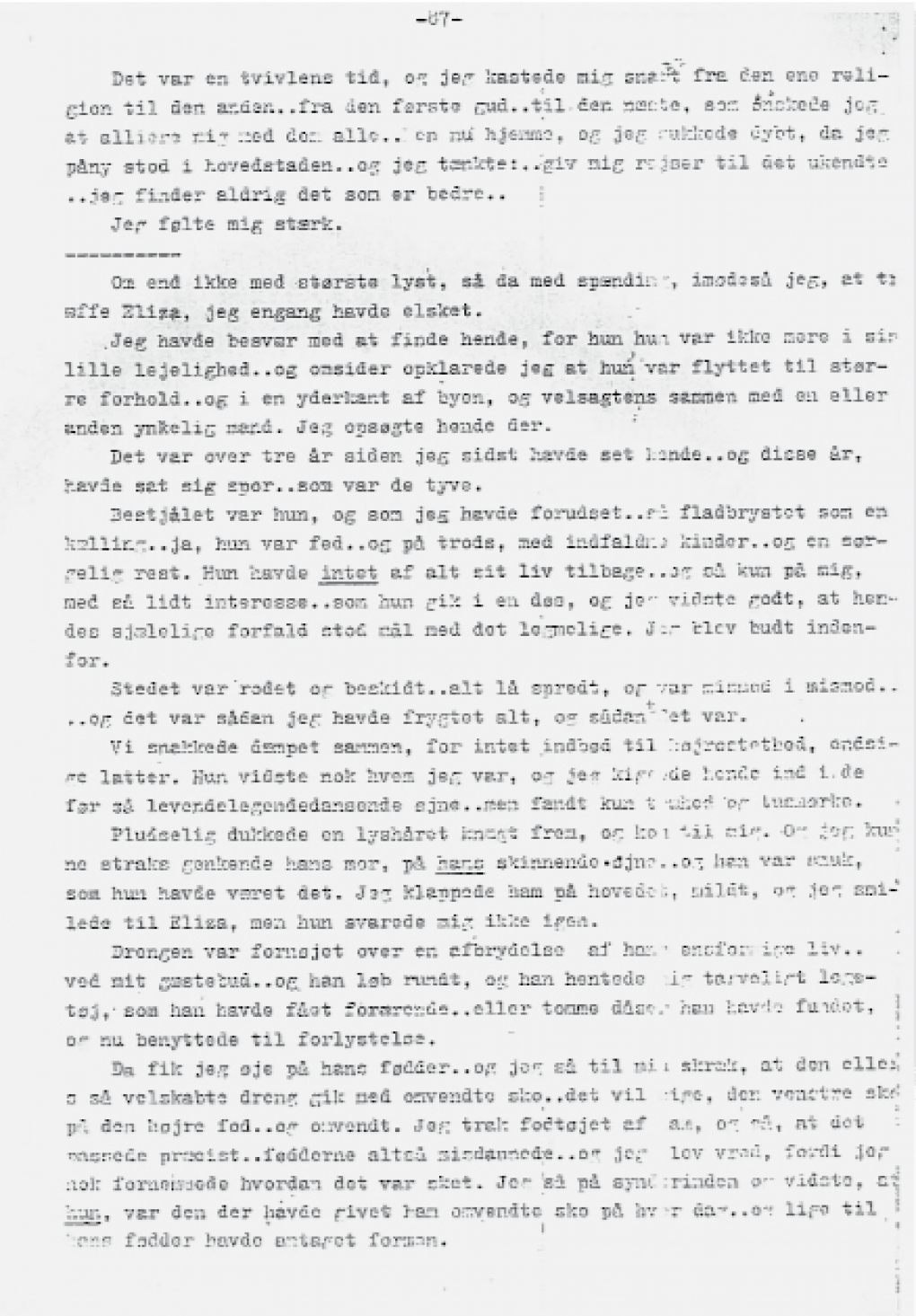

When he was 19-20 years old, Trier wrote several prose pieces including two complete novels (still under the name Lars Trier). The first was Bag fornedrelsens porte (1975, Behind the Gates of Abasement), and the next, Eliza eller Den lille bog om det dejlige og det tarvelige (1976, Eliza or The Little Book about the Delightful and the Vulgar), touches on the theme of the witchlike woman. Later, in The Orchid Gardener, Trier used some of the same, rather incoherent material. But other material from the novel, not used in The Orchid Gardener, found its way into Antichrist.

The male narrator of Eliza visits an actress after a theatre performance. He finds her ugly and disgusting, calls her “the witch”, but none the less he is caught in her web:

Yes, often one has to say that the nature of the witch and the woman is so closely related that bewitching is just believing a woman's words. 50

I had to neutralize the witch (…). Inactivating a witch is something that requires so much and not least patience. She lay beneath me … bleeding but deep in her witch interior, a place I could not see, a vengeance lurked like never before. I probably sensed it … was not sure and I could have no idea what evil was dormant.

I was and should come in great danger. 51

Later the narrator visits Eliza again:

Suddenly a fair-haired boy appeared and came to me, and I could immediately see his mother in his shining eyes … and he was beautiful as she had been. I patted him on the head and I smiled mildly at Eliza but she did not answer me back. (…) Then I caught sight of his feet, and I saw to my horror that the otherwise so well-built boy was wearing inverted shoes, viz. the left shoe on the right foot and vice versa. I pulled one shoe off him and saw that the foot fit exactly … it was deformed … and I got angry because I probably sensed how it had happened. I looked at the sinner and knew that she had given him the inverted shoes on every day, and right up to his feet had assumed such a form. 52

Trier’s novels were returned by several publishers and have remained unpublished. He has also kept the two films from the university years out of sight for a mainstream audience (they were only shown for an invited audience) but can occasionally be found on the Internet. Antichrist, however, makes it clear that his early apprentice work contains much that is still important for him.

In fact, I think (…) that Antichrist referred very well back to the first film I made, ‘The Orchid Gardener’ – with the male and the female. 53

Perhaps it is symptomatic that these immature works, by himself rejected and repressed, make themselves visible again when he suffers a depression. And there are other connections.

Trier has pointed out a certain scene in Antichrist as his favourite scene:

I am quite fond of the moment when Charlotte [Gainsbourg] goes out to the woodland and masturbates whilst her husband looks on, unsure of what to do. I think the atmosphere at this moment is very unique – it is a beautiful sequence also but it is also quite strange and even scary. I also have fond memories of doing that scene because I did not have to say much to Charlotte – she just knew what to do and how to portray this character. She worked like hell during this movie. 54

An interesting point, though, is that Trier’s description of the scene is incorrect: We don’t see that the “husband looks on, unsure of what to do.” He is not shown looking on. He just suddenly joins her. Perhaps it is rather Trier who ‘looks on, unsure of what to do’.

The masturbation scene, signalizing that ‘She’ can find pleasure without him, may refer to a scene in The Orchid Gardener, where a young woman is seen masturbating alone in a room. The strange scene has no obvious link to the story and was, contrary to the rest of the film, filmed by Trier himself with his former girlfriend in the role. 55

This scene takes place while a crying baby is heard outside the room; there is a change of actress, but it seems that we shall perceive it as the same person: first she corrects the child, then she masturbates. In another scene he is close to strangling her, but he doesn’t, it is not realised until Antichrist.

Both masturbation scenes have an affinity with Gustav Klimt’s drawings of masturbating women, pictures that probably were among the first in art history to show “women’s sexual self-sufficiency”. 56 The sexual acts can be seen as symptoms of voyeurism, but also as manifestations of a director who can use his authority to have the actors perform sexual acts. The director is in a position, like both the fiancé and Sir Stephen in The Story of O, who decide what sexual acts the woman must perform. This role is not always easy, though. In the gang bang scene in The Idiots, where Trier wanted his actors/actresses to simulate sexual behaviour in the company of two adult film performers, who provided the authentic sex, Trier was surprised that it was a challenge. 57

At the press meeting in Cannes, Charlotte Gainsbourg was asked, if Trier took her too far out. Trier answered, before Gainsbourg could speak: “Charlotte took it too far out. I tried to stop her, but I couldn’t”. 58 He can be said to work in the tradition of male directors (like Hitchcock and Kubrick) who are in a position to order and control sexual acts, performed or imitated by the female talent.

About his fascination of sexual perversity Trier has said:

Like Freud I see sexuality as a drive that really means a lot to humans. There’s probably a close connection between sexuality and art, but I can’t really expand on the point. Schepelern’s statement [“all in all Trier’s universe represents an unmistakable forum for sexual perversity” 59] sounds just fine. 60

Maybe it's actually a more aesthetic thing. Because those are some things that belong. It's one of the building blocks I work with. And if you ask me if it's something that comes from my personal preferences - yes, in part, but it's not that interesting. And besides, I am fond of habits and rites, as Sir Stephen pronounces in The Story of O. I work with the things that interest me - and these are some of the topics. And these perversions are also related to some people who are my heroes - the Marquis is my hero, and I was also happy with the night porter [Dirk Bogarde's role in Cavani's film]. After all, they do the same thing by taking things to extremes. 61

In his first feature, The Element of Crime, the relationship between Fischer and Kim has more than a touch of perversity as he is “fucking her back to the Stone Age” (on the hood of the Volkswagen), calls her a whore and pushes her through the window glass.

The perversity motif is absent from Trier’s next films, but it reappears in his later work. Especially Breaking the Waves had elements that anticipate Antichrist. In a 29-page treatment, dated August 24, 1992, Trier describes a scene, where Bess (in this version called Caroline), who has complied with her paralytic husband’s wish that she indulge in erotic experiences that she subsequently can tell him about, is picked up by a man who takes her out into the forest: “Just follow the stream until you get to the cabin”, 62 he says.

Inside the hut, which is decorated with antlers, three middle-aged men are sitting in deep armchairs, sipping cognac. The woman leads Caroline to the chairs. One of the men is smoking a cigarette. “Would you take your coat off?” Caroline removes her coat. Beneath it she is in black leather with a few straps and chains. Hooker gear. The three men look at her. There is complete silence. The woman paces about. Then she lights a cigarette. She steps up to Caroline and stands in front of her for a moment. Then she deals her a hard blow in the face. (…) The woman strips down to her panties and boots. She sits down on a carved wooden chair. She sinks back [bank] in it. “Come here then, you …” Caroline comes up to her and kneels down. She kisses the woman’s breasts. The woman seems unmoved. “Take them off …” She points at her panties. Caroline pulls them off. She caresses the woman’s labia with her lips. The woman lies for a while with her eyes closed. Then she opens them and looks at Caroline. “You know you’re going to have your bottom spanked, don’t you?” Caroline looks at her. “Yes”, she says quietly. The woman undoes Caroline’s pants and pulls them down. She hits her hard, again and again. The three men look on. 63

Then follows a scene outside the cabin:

The cabin in pouring rain. The woman opens the door. “You can go now”. Caroline pulls her coat around her. She steps out into the rain. The woman closes the door behind her. Caroline goes down to the street. She looks up at the clouds scudding across the moon. She sighs and tries to shake off what she’s just been through. We cannot see whether she is crying, because the rain is streaming over her face. She calms down. She hears a noise from the wood. She looks, but cannot see anything. She begins to walk along the stream. Suddenly he is on her. It is the man who said she was pretty cute. He knocks her to the ground. She screams in terror. He tears her clothes off her. She tumbles into the shallow water. He hits her to make her shut up. Now he holds her firmly by her hair while he screws her. She struggles to keep her head above water. He finishes. He rolls away from her and lies on his back in the water, motionless, his eyes closed. Caroline gets up and runs away. 64

The scenes are reminiscing of de Sade’s Justine, but also of Pasolini’s Salò, freely adapted from de Sade’s 120 Days of Sodom. Here a handful of middle-aged men and some women perform atrocities on a group of young women and young men who are kept imprisoned in a remote estate in fascist Italy. The film had a short run in Denmark in 1976 and was re-imported and reissued in 1999 on the initiative of Christian Braad Thomsen and Trier.

Significantly, the perverse scenes in the Breaking the Waves treatment didn’t find their way into the script and were never filmed. The only trace in Breaking the Waves of brutal sexuality is a scene where Bess has sex with a man she has picked up in a bar. They drive out and are shown lying on the ground against the landscape. In the original treatment they are in a rowboat. 65

In the published manuscript their lovemaking is crosscut back and forth with Ian in critical condition on the operation table. “The man fucks Bess violently”, it says, but Bess “slips in and out of total surrender. She will not let herself go.” Ian is about to fade away, when “(s)uddenly Bess’s body is gripped in the throes of an incredibly violent orgasm. She screams.” As if activated by this, Ian’s heart restarts, while flocks of birds are “shooting in the air at Bess’s scream”. 66 In the film, the scene is reduced to a few seconds showing the two fornicating on the ground with a close up of Bess expressing disgust. No orgasm, no scream, no birds. And no cross cutting, though is still appears as if Ian is saved because Bess has sex with a stranger.

Freud and the Artist

In Antichrist She refuses to hear about his dreams and asks sarcastically: “Freud is dead, isn’t he?” But Trier’s own career matches rather precisely Freud’s classical characteristics of the artist (who for Freud necessarily had to be a man):

An artist is once more in rudiments an introvert, not far removed from neurosis. He is oppressed by excessively powerful instinctual needs. He desires to win honour, power, wealth, fame and the love of women; but he lacks the means for achieving these satisfactions. Consequently, like any other unsatisfied man, he turns away from reality and transfers all his interest, and his libido too, to the wishful constructions of his life of phantasy, whence the path might lead to neurosis. There must be, no doubt, a convergence of all kind of things if this is not to be the complete outcome of his development; it is well known, indeed, how often artists in particular suffer from a partial inhibition of their efficiency owing to neurosis. Their constitution probably includes a strong capacity for sublimation and a certain degree of laxity in the repressions which are decisive for a conflict. An artist, however, finds a path back to reality in the following manner. To be sure, he is not the only one who leads a life of phantasy. Access to the half-way region of phantasy is permitted by the universal assent of mankind, and everyone suffering from privation expects to derive alleviation and consolation from it. But for those who are not artists the yield of pleasure to be derived from the sources of phantasy is very limited. The ruthlessness of their repressions forces them to be content with such meagre day-dreams as are allowed to become conscious. A man who is a true artist has more at his disposal. In the first place, he understands how to work over his day-dreams in such way as to make them lose what is too personal about them and repels strangers, and to make it possible for others to share in the enjoyment of them. He understands, too, how to tone them down so that they do not easily betray their origin from proscribed sources. Furthermore, he possesses the mysterious power of shaping some particular material until it has become a faithful image of his phantasy; and he knows, moreover, how to link so large a yield of pleasure to this representation of his unconscious phantasy that, for the time being at least, repressions are outweighed and lifted by it. If he is able to accomplish all this, he makes it possible for other people once more to derive consolation and alleviation from their own sources of pleasure in their unconscious which have become inaccessible to them; what originally he had achieved only in his phantasy – honour, power and the love of women. 67

Young Trier’s first projects were filled with anxiety, perversion, and sexuality in an un-clarified mixture that was far too extreme and bizarre to obtain a response. The early novels were refused by the publishers, and he was not accepted at the Academy of Arts. But even though Trier has told how his co-students, when they saw The Orchid Gardener, only had one question to him – “Why??” 68 – the film actually helped get him into the National Film School of Denmark. And from the perversities and the traumas of The Orchid Gardener and Menthe the Happy One (as well as in early paintings and novel drafts), far too personal and extreme to be accepted by others, Trier found artistic and technical command with The Element of Crime and Europa and thereby at least professional respect. When he finally, with The Kingdom and Breaking the Waves, achieved wide international recognition and even popularity, it was not because his neuroses now were less explicit, but because he now understood to communicate them more generally.

He has himself been aware of this:

As for the provocative themes, in that respect I haven’t changed at all. I still deal with exactly the same things, but in a more controlled way. 69

With Antichrist, the merger of private and general neuroses reached a temporary peak. The film was vilified and damned by many, but at the same time it confirmed Trier’s status at the top of the global auteur directors. And when Charlotte Gainsbourg won the prize as Best Actress in Cannes it signified that the character, no matter how horrible ‘She’ might seem, nevertheless was considered somehow plausible. The private neuroses and anxieties were accepted as something of general relevance.

The film can be seen as a revival of the complexity and perversity of the early universe, a portrait of the artist as a young man, retrouvé and challenged, returning to all the unfinished businesses of youth. It was a relapse for the patient back into the early traumas, haunted by sexual perversion and depravity, evil women and witchcraft.

In this respect Trier’s claim that it is “the most important film of my career” 70 can be explained. It can be compared to Tarkovsky’s The Mirror – and the film is indeed dedicated to Tarkovsky. Similar to The Mirror, Antichrist is not necessarily the most important for the audience, but his most personal film. It has the same complexity, the same ambiguous layers of meanings and symbols, perhaps unclear but certainly disturbing for the audience, and with necessity for the auteur himself.

It is art as self-therapy, but at a level where an audience accepts it. His traumas, his inspirations, his unfinished business from the early years go together in a synthesis, echoing Ibsen’s famous verse (1878): 71

To live is to battle the demons

In the heart as well as the brain.

To write is to preside at

Judgment day over one’s self.

Fin-de-siècle Misogyny

During his work on the manuscripts in 2007-08, Trier had assistants and specialists make research in various subjects that could be of relevance to the script, mainly assistant Kathrine Acheche Sahlström (the mother of the young Storm who is Nic), specialists Heidi Laura, Rikke Schubart, Line Holt (Kvinfo), Lise Præstgaard Andersen, Jens-André P. Herbener, Paul Lübcke (theological advice) and Lisbet Lassen who contributed with statements, pictures, surveys, examples and bibliographies on misogyny, persecution and abuse of women, evil women and horror films. Parallel, one could say, to the research that She made for her thesis.

This is Trier’s usual working method. He has a number of researchers and specialists make short papers and useful definitions and quotations; often he has a session where he can interview and discuss the issues.

Working on Antichrist, Trier received a large material from his research assistants, covering Satan, anxiety, evil, demons, suppression and hate against women, original forests, evil women. The consulted misogynist classics include a famous but unauthentic dictum by Pythagoras (quoted By Simone de Beauvoir 72): “There is a good principle which has created order, light and man; and a bad principle which has created chaos, darkness and woman.” There is the British Malleus Maleficarum (1486): “And I have found a woman more bitter than death, who is the hunter’s snare, and her heart is a net, and her hands are bands. (…) All witchcraft comes from carnal lust, which is in women insatiable.” 73 The statement that “A crying woman is a scheming woman” 74 is seemingly in Trier’s own words, though versions of a similar idea are known. 75

But the view on women and women’s sexuality in Antichrist seems primarily to be connected to the fin-de-siècle in European culture, an important source of inspiration for Trier at the beginning of his career. Both in literature, theatre, painting and thinking, especially in German-language cultures, there was a huge trend of more or less misogynist presentation of women: the woman was seen as bearer of illness, folly, collapse, but also seduction and temptation, women as fatal Idols of Perversity (cf. Bram Dijkstra 76).

The Austrian writer Arthur Schnitzler, an acquaintance of Freud, who acknowledged him as a source of inspiration, was a pioneer in the presentation of sexuality, mainly with the daring play Der Reigen (La ronde), where each of the ten scenes culminates with a couple having sexual intercourse. It was published 1903, but didn’t have its first stage performance until 1920, when it was prohibited by censorship; later filmed by Max Ophüls (1950) and Roger Vadim (1964). In the novella Traumnovelle (1925; filmed by Kubrick as Eyes Wide Shut, 1999), Schnitzler’s focus is on female sexuality as an irrational threat of disaster and devastation: the young wife and mother confesses to the husband one of “those hidden, hardly suspected wishes” 77 that she once, during a vacation in Denmark, actually, was instantly attracted by a male guest, feeling that she was ready to leave husband and child if he had asked her to follow him. Another characteristic figure of the same era is the German Frank Wedekind whose dramas Erdgeist (Earth Spirit, 1895) and Die Büchse der Pandora (Pandora’s Box, 1904) present the fatal Lulu, the iconic femme fatale, who, seemingly unintentionally, destroys men (also adapted for film and opera, cf. Leopold Jessner, G.W. Pabst, Alban Berg). 78

The She of Antichrist can be seen as a synthesis of the female prototypes of the fin-de-siècle art and fiction: She is weak and vulnerable, faints, she depends on male help, she shows symptoms of folly, she tries with her lust to draw the man into the abyss. She is a mix of the saintly vulnerable woman and the lusty femme fatale. And her sexuality is finally revealed as a demonic, destructive power.

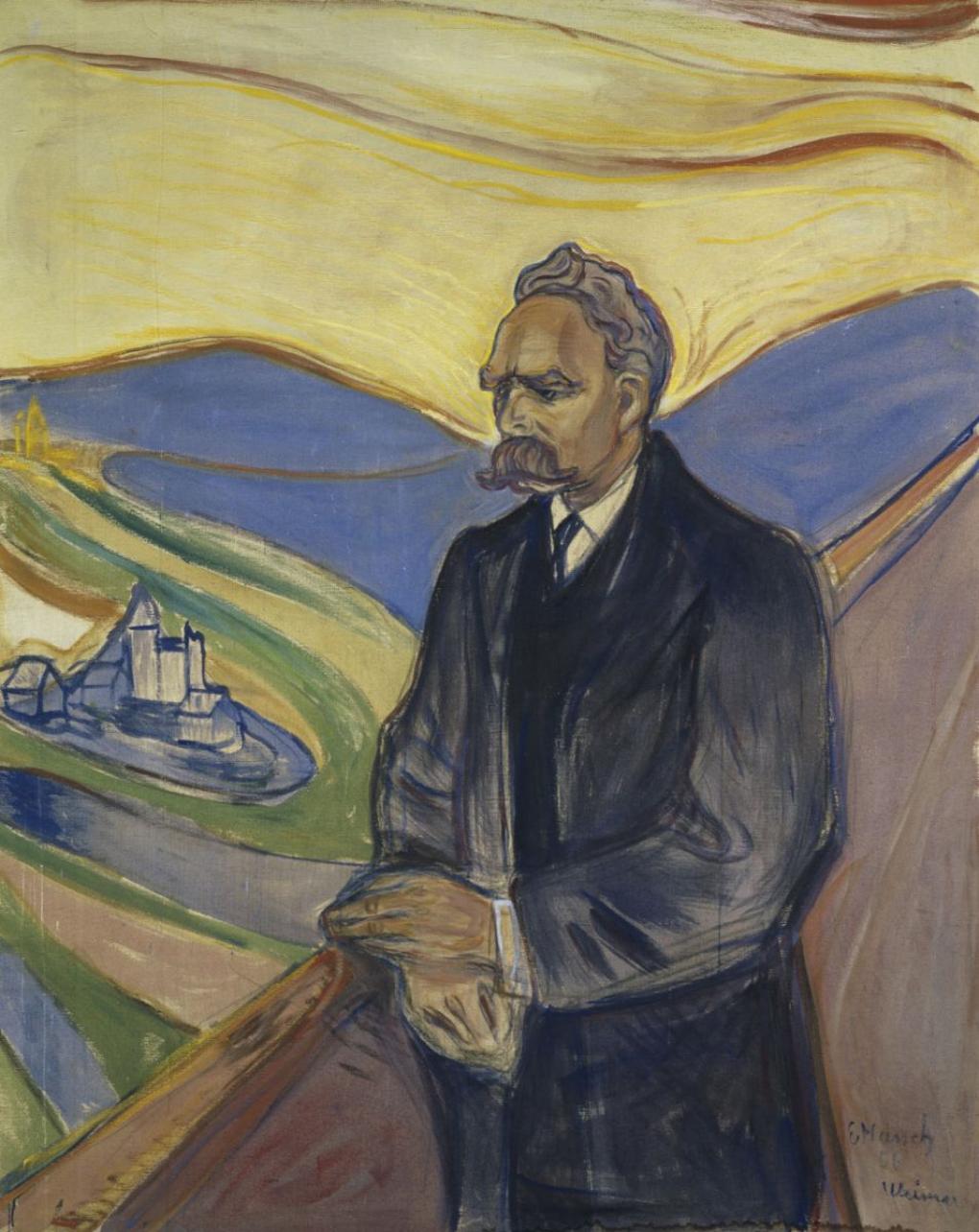

Thus, Antichrist can be seen as a fable about sexuality and desire where crucial fin-de-siècle figures in European culture are implicitly summoned together in a symbolic rendezvous, mainly Nietzsche, Strindberg, Ibsen, Munch, Freud. Most of the ideas and interpretations of female sexuality in Antichrist are explicitly or implicitly linked to this group of outstanding men who somehow hated women and saw sexuality as an alluring and fatal power.

Foucault summarizes the view on sexuality in this period as

the point of weakness where evil portents reach through to us; the fragment of darkness that we each carry within us: a general signification, a universal secret, an omnipresent cause, a fear that never ends. 79

The central figure of the group, the mad genius of the era, was of course the German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900) who made his imprint on the whole era.

The major artistic currents at the beginning of the century, symbolism, art nouveau, expressionism - were all inspired by Nietzsche. Back then, everyone in these circles who was self-conscious had their 'Nietzsche experience. 80

Nietzsche’s view on art, influenced by his fascination and later dismissing of Richard Wagner (who would later be a major fascination for Trier), 81 has, as here summarized by Rüdiger Safranski, an obvious relevance for Trier’s Antichrist:

What is the power of art? It creates a magic circle of images, imaginations, sounds, ideas that cast a spell and transform everyone who gets into the circle. 82

Trier had an early interest in Nietzsche. When Antichrist takes its title from Nietzsche’s book, written in 1888 shortly before the outbreak of his insanity (published in 1895), it can be understood as an homage – and a nostalgic reference. Allegedly Trier had the book (Danish translation 1973) on his night table for years, but never actually read it. 83 However, in a short autobiographical sketch of 1976 he mentions that he “worked himself through Nietzsche.” 84 He has pointed out that Liliana Cavani’s Nietzsche film, Al di là del bene e del male (1977, Beyond Good and Evil), more about sex than about philosophy, made a deep impression on him. 85 And when in 2006 he wrote a film manuscript based on his experiences at the National Film School of Denmark (De unge år/The Early Years, 2007, directed by Jacob Thuesen), he chose as his alias the name Erik Nietzsche (both the name of the main character and the pen name of the scriptwriter).

Trier seems to feel a certain kinship with Nietzsche’s provocative, transgressing attitude, and with the mad genius at large. Nietzsche’s own characterization of his book (in the draft of a letter to the Danish critic Georg Brandes who more or less discovered Nietzsche and made him famous) fits quite well with Trier’s film:

My book is a volcano, one has from the literature so far no idea of what it means and of how the deepest secrets of human nature suddenly jump forth with appalling clarity. 86

Nietzsche’s Antichrist furiously attacks Christianity and the church, and Trier’s film too can be seen as an anti-religious allegory, but the Nietzschean perspective lies mainly in the view on the woman.

In his famous Also sprach Zarathustra (1883-85, Thus Spake Zarathustra), the prophet has some advice: ““Thou goest to women? Do not forget thy whip!” and warns about the man’s no-win situation: “Let man fear woman when she loveth: then maketh she every sacrifice, and everything else she regardeth as worthless. Let man fear woman when she hateth: for man in his innermost soul is merely evil; woman, however, is mean.” 87

And in Antichrist Nietzsche also states his well-known misogyny:

Woman was the second mistake of God. – “Woman, at bottom, is a serpent, Heva”– every priest knows that; “from woman comes every evil in the world”– every priest knows that, too. 88

A later case, also presented in the research material, Trier had at his disposal, concerns the Jewish Austrian philosopher Otto Weininger, whose Geschlecht und Character. Eine prinzipielle Untersuchung (1903, Sex and Character) is one of the misogynist classics of modern times. The author, whose competence on the subject is not very obvious, committed suicide at 23 shortly after the publication of his work that was a big success in the early years of the 20th century – an English translation came in 1906. Though it now appears as a treasure box of male chauvinist (and Anti-Semite) nonsense, it collects and summarizes typical gender attitudes of the era.

The message of the book was summed up by an admirer:

In the last analysis, the woman's love is said to contain fifty percent heat and fifty percent hatred. It sounds weird, but it's so. Regardless of inclination and taste, opinions and such, one finds that when a woman loves a man, she hates him; hates him because she feels bound to him and inferior to him. There is no constant current in her love, but a constant repolarization and a constant current change; in it the negative, the passive in her being, appears in contrast to the man's positive, active. 89

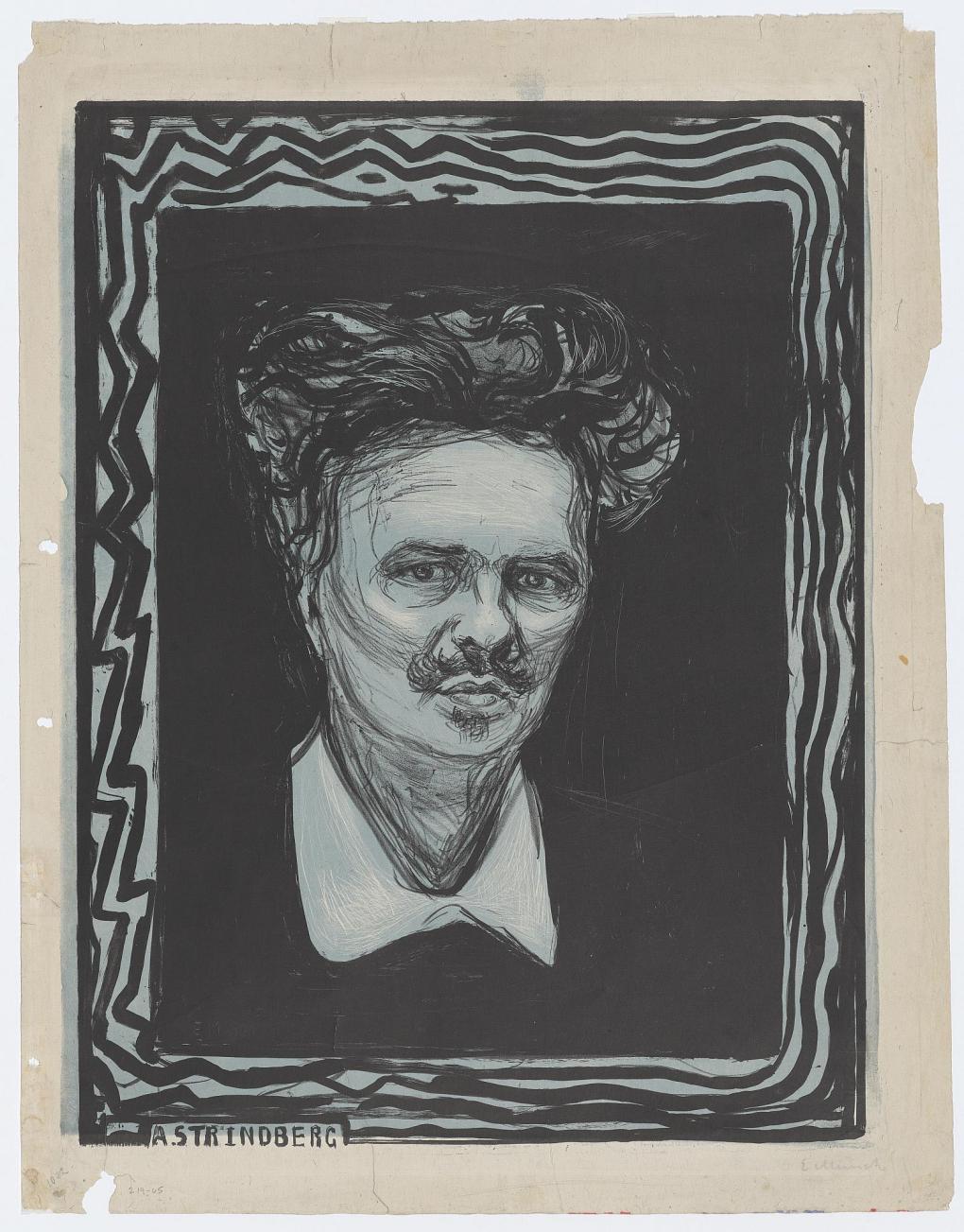

The words come from the Swedish writer August Strindberg (1849-1912), a central figure in Scandinavian literature and in world drama who has been Trier’s cultural hero since the early years.

Strindberg and Inferno

It was not least Strindberg’s notorious misogyny that fascinated Trier.

I was really fascinated by Strindberg’s totally preposterous attitude to women. Much of it concerned such a power battle between men and women, and I could see myself in him. That is his furiousness and his childish behavior to the opposite sex and his self-appointment as a genius. He exclaimed himself a genius and then he acquired something that considerably looks like delusion of grandeur in this inferno crisis, where it totally ran off the tracks and he signed himself Rex and God. I loved it. 90

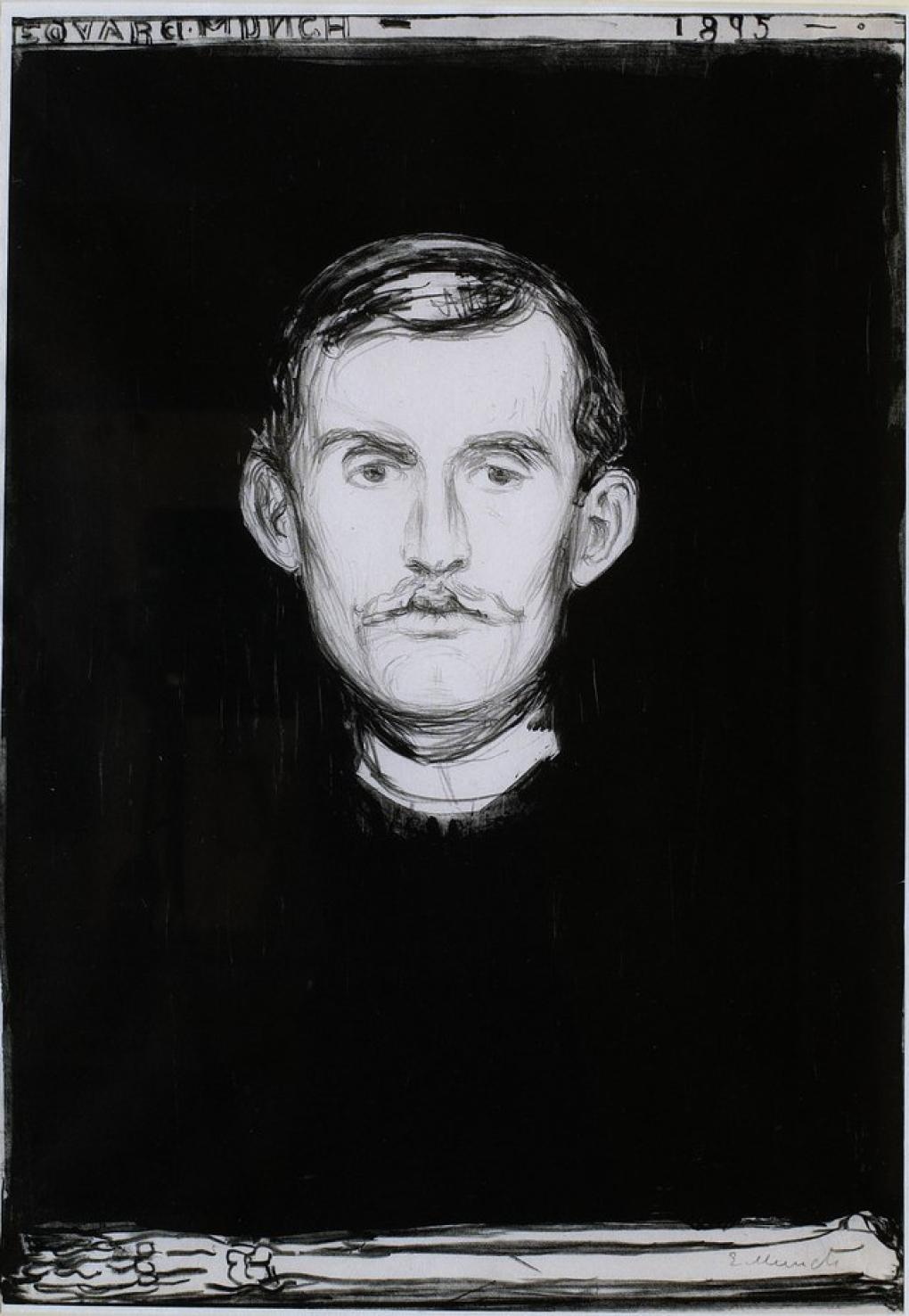

Young Trier’s first public manifestation was an article in a local weekly newspaper, “På vanvidets rand i Holte” (At the Edge of Madness in Holte), Det grønne område January 28 1976. 91 The article discusses genius and madness with main focus on Strindberg but also discusses the Norwegian painter Edvard Munch and the German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche. Both Strindberg, Nietzsche and Munch would influence Antichrist’s vision of woman and female sexuality.

In the by-line of the article the 19-year old Trier is identified as a “writer and artist”. Already here he calls himself Lars von Trier and is shown on the accompanying photo standing dressed in black with long shafted riding boots in front of the estate Skovlyst (the word means Forest Pleasure; now Geelsgårdskolen, an institution for handicapped children) situated in Virum (near Holte), close to Trier’s home in Lyngby, an affluent suburb north of Copenhagen. It was here that Strindberg in the eventful summer of 1888 wrote his seminal Miss Julie, a one-act play about repressed sexuality and childhood traumas focused on two characters, the young daughter of the manor house who has a sexual encounter with the servant Jean. This was also the place where Strindberg, who was accompanied by his wife and their three small children, had a brief affair with the bailiff’s teenage sister, later described in the short historical novel Tschandala (1889).

In the family book collection, Trier had access to the standard Danish Strindberg edition (eight volumes 1921-1928) and he had read the literary historian Harry Jacobsen’s work on Strindberg and Denmark, Digteren og Fantasten: Strindberg paa “Skovlyst” (1945, The Poet and the Dreamer: Strindberg at “Skovlyst” – ‘Skovlyst’ meaning: Forest Pleasure), and summarizes the story about Strindberg’s decisive but also controversial and dramatic stay in Denmark.

The article ends with a general comment:

The old truth about the floating boundary between genius and madness must once more be taken out if it is not so that man’s cry for genius is just a wish for abnormities for mankind’s own soothing and that there so is no boundary at all between brilliant intellect and raving lunacy. 92

Later Trier reflected on the topic of artistic production and psychiatric disorder:

It is interesting that both Strindberg and Munch came to Copenhagen to be cured by Professor Jacobsen, who was the great Danish psychiatrist of the time. (…) But Strindberg’s novels got much duller and Munch’s paintings were far less interesting after their meetings with Professor Jacobsen, so he was a bit of a villain in my eyes. They might have felt better, but their art was damaged by those consultations. (…) No, artists are meant to have it bad, because it makes the results so much better! 93

Trier was also aware of the modern Swedish writer Per Olov Enquist, whose debut stage play about Strindberg, Tribadernas natt (The Night of the Tribads, 1975), became an international success; in Copenhagen theatres in 1976 and 1977, shown on Danish TV 1978. Ernst-Hugo Järegård, who played the main role in the original Stockholm production, would later appear in Trier’s Europa and The Kingdom. When Trier in 1975 year applied for admission to The State Theatre School in Copenhagen, where he wanted to study theatre directing but was not accepted, he enclosed his production plan for this play. He also read En dåres försvarstal (The Defense of a Fool), Strindberg’s account of his first marriage (adapted for Swedish TV in 1976, aired in Danish TV the same year).

In a period (1896-97) Strindberg was tormented by visions and anxiety described in the novel-like text Inferno (1898), allegedly based on the writer’s diaries. It has since been argued, particularly by Olof Lagercrantz in his ground-breaking biography August Strindberg (1979, English translation 1985), however, that Inferno is a deliberate literary adaptation that in many cases has no connection to the diaries. “August Strindberg writes about August Strindberg but those two are not the same person.” 94 And he finds the “key” to the Inferno crisis: “Strindberg listens with his inner ear and contributes reality to his fantasies and dreams but he doesn’t mix them with the reality of the exoteric life.” 95 Strindberg the person was tormented by his mental troubles but at the same time he was able to regard it as useful material for Strindberg the writer. He was “a very conscious artist, who cultivated his pathological ideas to get material to write about.” 96

This interpretation of Strindberg’s crisis can be compared to Trier’s as he hypothetically does himself:

I read Strindberg when I was young. I read with enthusiasm the things he wrote before he went to Paris to become an alchemist and during his stay there … the period later called his “inferno crisis” – was “Antichrist” my Inferno Crisis? My affinity with Strindberg? 97

Trier underlines that he made the film “using about half of my physical and intellectual capacity”. 98 He was psychologically disabled, but at the same time he understood to use his personal crisis in a creative way as artistic material. The whole idea came out of depression, nightmare, visions, traumas and therapeutic experiences.

For a long time, I’ve been suffering from a deep depression. It’s been a real hell. For a while I was just lying in bed, staring into the wall. But writing became a way of getting through – a means to try and conquer this state of mind and get out of bed.” 99

I would rather see it as some wreckage that one clings to. The movie was also made for me to feel better or have something to do. The wreckage that was inside me, I then took out and made a film about or from. Then I felt better. 100

The film appears as a fantastic vision, an enigmatic sight taken from the depths of a haunted mind. But at the same time, there has been worked very concretely, pragmatically and methodically. A German commentator notes that: “All this is calculated, the conscious action of a filmmaker who is in complete control of his means even after his personal crisis.” 101

Strindberg’s misogyny is a constant and notorious theme in his work, most evident in passages in Inferno, in the foreword to the second part of the controversial short story collection Giftas – “All the dark sides of history ... depend on the woman” 102 – and in his last major work, the so-called En blå bok (A Blue Book, 1907). Here he states: “He that doesn’t believe in the devil, he should see an evil woman up close.” 103 But also in his dramas he presents the hostility between spouses with unique intensity, more bitter than any other classical writer – most demonstratively in Fadren (The Father, where the wife drives the husband into insanity) and in Dödsdansen (Dance of Death about a bitter marital couple), as well as in the autobiographical novels Han och Hon, also about a He and a She, and En dåres försvarstal (The Defense of a Fool), more or less explicitly based on his own marital experiences.

Trier defends Strindberg:

There is a struggle between the sexes. (…) And although some of Strindberg's misogyny was hysterical, it does carry a small part of the realities. 104