Introduction: The Politics of Distributing Movies

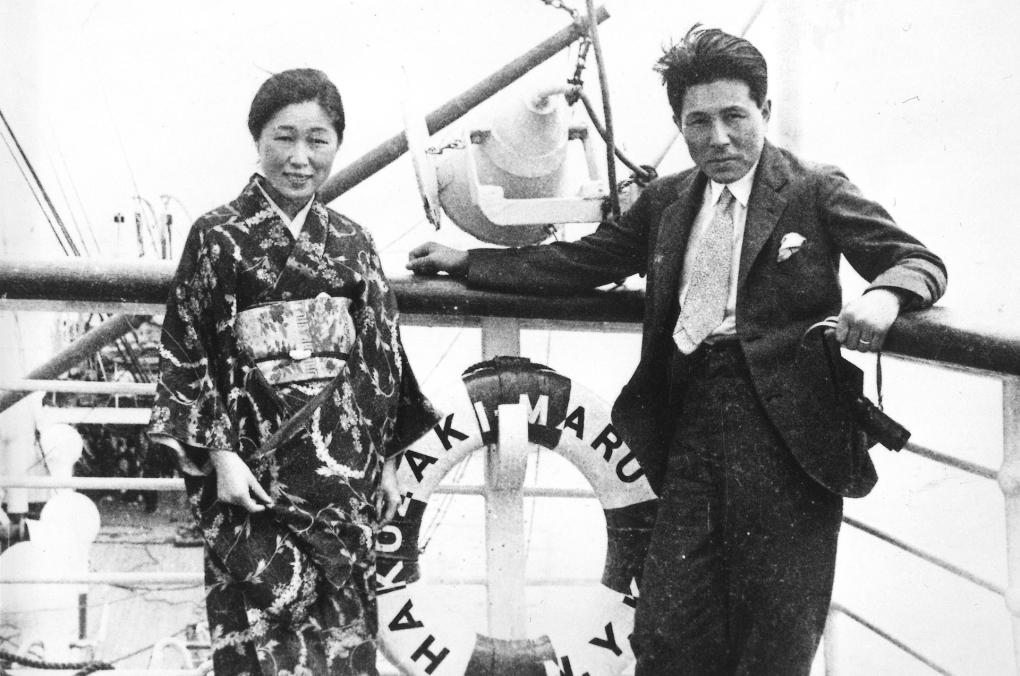

In film production and distribution history, few couples have operated as fluidly as Kashiko and Nagamasa Kawakita.1 Across several decades, they worked to provide Japanese audiences with a cinema experience that went beyond the realms of the expansive Japanese film market and the overpowering presence of American films in Japan. In 1928, after working a few years in tandem with Taguchi Shoten (田口商店), Nagamasa Kawakita (川喜多長政, 1903-1981) established the Towa Shoji Goshi Kaisha (東和商事合資会社, now Toho-Towa Limited, 東宝東和株式会社) in part to bring European films to Japan but also to export Japanese films to the world. On October 10, 1929, Nagamasa married his secretary, Kashiko Takeuchi (竹内かしこ, 1908-1993), and together they spent the next 50 years searching the world for films suitable for the Japanese market, bringing about a significant cross-cultural exchange through cinema. In 1932, on an overdue honeymoon, the pair traveled by boat to Europe. The primary purpose of the trip was to strengthen their business connections and secure an extensive collection of German sound films for release in Japan. Additionally, the changeover to sound film meant the Kawakitas were exploring new market possibilities for dubbing and sound equipment. Along the way, Kashiko kept a diary of daily activities, recording in short detail the people, companies, films, and places. Published in Japanese in 1942, Kashiko’s writing has remained a relatively obscure—yet available—document.2 Our discovery of this invaluable journal, which minutely details the turmoil of the film industry in Germany and Japan, came about through our research of the first Towa Shoji production, Nippon (1932).

Through a close reading and external research, we contend and will demonstrate that Kashiko’s journal is a significant map for connecting the complex inner workings of the global film market during the Great Depression. The chronicle offers an early 20th-century image of a confident Japanese businesswoman collaborating with her partner while distinguishing her aptitude for negotiating within the film industry. Within the text, details of seemingly inconsequential references provide a glimpse into the depression-era international film market, demarking a complex network of people and companies between whom the Kawakitas were maneuvering to expand the capability of Towa Shoji to provide European cinema in Japan.

One of the founding objectives of Towa Shoji was simple: reduce the dominance of American cinema in Japan by importing European productions.3 Such sentiments were shared in continental Europe, where the respective governments had placed strict quotas on the number of American films that could be imported. Between European countries, some regulations significantly curtailed cross-border exports and imports. In Japan, which produced more films per year than almost any other country, the predominance of American films held firm. When Towa Shoji was established in 1928, the Japanese cinema owners had already made a concerted effort to protect their film industry, with 56% of Japanese theaters showing only Japanese silent films. However, in total, American silent films consisted of 10.6% of movies. By 1932, when the Kawakitas traveled to Berlin, their options for securing Japanese theaters to show German film imports had dwindled to less than 30% of theaters in Japan, and within this group, American films dominated 45% of the foreign sound films.4 While often considered a laggard in the changeover to sound film production and exhibition, the Japanese film market was steadily moving into the sound era by 1932. When the Kawakitas left for Europe, they would return with German contracts for only sound productions; they would also bring back firsthand knowledge of the newly forming dubbing industry in Germany. Even though cinema remained profitable, the longevity of the Great Depression was taking its toll. In 1932 Germany, several producers and distributors faced bankruptcy, and roughly thirty percent of movie theaters had ownership changes or closures.5 The shift from silent to sound films had been financially destabilizing globally, and the transition particularly hit Japan, where they were initially dependent on foreign technology to convert theaters. In September 1932, out of Japan’s 1500 movie theaters, only roughly 45 had been converted for sound films, thus limiting the locations where German sound imports could be shown.6 Additional complications arose for Japanese film importers due to the collapsing value of the Japanese yen and import quotas. As demonstrated through the diary, such tensions would not bypass Towa Shoji.

During these transformative years of cinema, the Kawakitas were no ordinary team. The mere fact that they were Japanese in Europe gave them celebrity status in their respective business circles. Additionally, being a husband-and-wife team also garnered admiration, as The Japan Times noted that Kashiko was “an expert in the publicity side of this interesting collaboration. She knows everything about the plays and players, and translates the details into Japanese for newspapers and magazines at home.”7 Their reputation can be easily recognized in the numerous media articles mentioning Kashiko and Nagamasa. Years later, when Kashiko would travel to Europe without her husband, her association and friendship with such individuals as Henri Langlois (1914-1977), co-founder of the La Cinémathèque Française, certainly bolstered her acumen within the cinema industry. In terms of academic publications, Iris Haukamp’s A Foreigner’s Cinematic Dream of Japan: Representational Politics and Shadows of War in the Japanese-German Coproduction New Earth 1937 (2020) goes into great detail concerning the Kawakitas and their role in sharing Japanese culture, documenting their efforts with the 1937 joint film production, Die Tochter des Samurai (The Daughter of the Samurai, 1937). The Japanese version of this film was jointly directed with Mansaku Itami (伊丹万作, 1900-1946) and was titled New Earth (新しき土, 1937). Concerning Towa Shoji’s connection with Universum Film-Aktien Gesellschaft (Ufa), Karl Sierek has written extensively in Der lange Arm der Ufa: Filmische Bilderwanderung zwischen Deutschland, Japan und China 1923-1949 (2018, The Long Arm of Ufa: Cinematic Image Migration between Germany, Japan, and China 1923-1949). In Japan, publications mentioning the Kawakitas and Towa Shoji include Shojiro Tsuji’s “Towa Shoji and Accomplishments of the Kawakitas”; Kae Ishihara, History of Film Archiving in Japan (2018); and Tsuchida Tamaki’s “The Concept of Internationality in Prewar Japanese Cinema: Kawakita’s Dream in Nippon.” A few memoirs have referenced the Kawakitas, including Fragrant Orchid: The Story of My Early Life (2015) by Yamaguchi Yoshiko.8 Considering the number of French films Towa Shoji imported, including Julien Duvivier’s successful Poil de Carotte (The Red Head,1932), and the close relationship Kashiko later had with Langlois, surprisingly scant mention of the Kawakitas appears in modern French film scholarship.

Not surprisingly, the Kawakitas made a significant effort to record their personal history and the importance of Towa Shoji. Nagamasa Kawakita provided historical recollections in a serialized newspaper section entitled “My Resume” (私の履歴書). Published in thirty installments through the Nihon Keizai Shimbun (日本経済新聞), he records (sometimes inaccurately) essential events throughout his life. “My Resume” was republished in the Towa Shoji 60th anniversary publication, and there is also an English translation of the book that was privately published. This English text, along with Kawakita’s minor historical inaccuracies, is further compromised by the translators who removed sections from the text, making it a somewhat flawed translation and, in the opinion of the authors, should be avoided. The Chinese translation of “My Resume” (川喜多長政《我的履歷書》中文版, 感恩而死翻译作品) seems true to the original. Additionally, Towa Shoji published five commemorative books detailing the company's history and provided a list of films distributed in Japan. In their first publication (1942, reprinted in 2015), Kashiko incorporated her travel diaries of 1932, 1934, 1935, and 1938. For the most part, only Japanese scholars have utilized Kashiko’s diaries, thus leaving a void in Western research. Therefore, a documented explication of the 1932 diary will be a crucial document for cinema lovers and scholars of early sound film history in Europe and Japan.9

An additional aspect that enhances the significance of the diary concerns the political climate involving Japan and its image in Europe. The Kawakitas left Japan a few weeks after the assassination of the Prime Minister of Japan, Inukai Tsuyoshi (犬養毅, 1855-1932). The news of his death would spread around the globe, fueling the political turbulence that emerged after the attempted assassination of the Emperor of Japan in January and the continued escalation of tensions that would eventually lead to the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937-1945), resulting from the Japanese occupation of territories in China. Further complicating problems between Japan and Europe was the First Battle of Shanghai (often referred to as the “Shanghai Incident”), when the Japanese government directed its troops and navy to attack Chinese soldiers to defend the Japanese settlements in the region experiencing discrimination. The fighting lasted into March 1932 and killed thousands. At the time, Shanghai was home to numerous international enclaves and one of the most important cities in China. Attacking China’s largest city created international pressure against Japan and, therefore, brought about a ceasefire. Connections between Shanghai and Europe meant that the conflict negatively impacted business relations.

Furthermore, the battle renewed negative attention to the illegitimate Japanese Manchukuo regime (considered Imperial Japan’s puppet state in Manchuria). When the Kawakitas reached Berlin, they would find themselves in a milieu decidedly anti-Japanese. These events should also be considered in the global economic environment, which, coupled with the expensive transition from silent to sound and dubbed films, meant radical and rapid changes occurring within the film industry. A depressed film market and the Japanese government’s decision in December 1931 to leave behind the gold standard meant that the Kawakitas arrived in Berlin with weakened purchasing power. This monetary situation would enact a significant turn of events for Towa Shoji by the time the Kawakitas left Berlin. Conversely, Germany also had substantial political turmoil, including violence and assassinations. The Kawakitas essentially exchanged one volatile climate for another. Throughout the diary, there are various indirect and sometimes direct references to the political climate of Berlin. Here and there, clues emerge as to just how close Hitler’s political party was crisscrossing the steps of the Kawakitas.

From Asia to Europe: The Honeymoon Business Trip

Their journey out of the port of Yokohama, aboard the Hakozaki Maru (箱崎丸) of the NYK Line, commenced on May 29 with overnight stops in Nagoya, Osaka, and Kobe. They then traveled through the Seto Inland Sea to Moji City, Fukuoka Prefecture, before leaving Japan on June 4. After an uneventful night at their branch office in Nagoya, they disembarked in Osaka on May 31. Since its founding in 1928, the expansion of Towa Shoji had been rapid, and the company held branches or representatives in the cities of Sapporo, Nagoya, Osaka, Kobe, and Fukuoka, with overseas locations in Shanghai, Dalian, and Keijō (Seoul). In September 1930, they placed Ishikawa Toshishige (石川俊彥) in charge of the Osaka branch management. Originally from Honjō, Saitama Prefecture, Ishikawa became involved with cinema through his participation in one of the earliest film magazines in Japan, The World of Motion Pictures (活動之世界).10 When the Kawakitas arrived in Osaka, they visited their branch office, meeting with Ishikawa. Undoubtedly, one of the topics they discussed was maintaining a profit in the face of increased import costs and decreasing revenue from cinemas. In 1931, the Tokyo region established a consortium of distributors and theater owners joining together to pool their financial resources. The organization was dubbed the “SP Chain (SPチェーン),” short for the Shochiku Pasha (Paramount) Cinema Chain (松竹パ社興行社), directly connected with Paramount Pictures and the distribution of foreign films in Japan. In Osaka, Ishikawa was undertaking a similar effort to combat the double financial burden: the recession and the advancement of the Japanese talkies. The foreign film distributors and cinema owners struggled to maintain profits due to disagreements between each group. Since the Kawakitas intended to make multiple film purchases in Germany, they needed to ensure that their efforts and expenditures would be rewarded and bolster the future of Towa Shoji. After their departure, Ishikawa, among others, was appointed to the leadership of a collective of foreign-language film distributors that succeeded in forming the Kansai Distributors Union (関西配給者聯盟) to help reduce expenses concerning foreign language film imports.11

After moving from Osaka to Kobe, they were seen off by Ishikawa from Osaka and Aoyama Tadaichi (靑山唯一), who, in September 1933, would join Towa Shoji as the advertising manager for the Osaka branch. Like Ishikawa, Aoyama was a regular contributor to the national film magazines. After joining Towa, he continued writing for Kinema Junpo (キネマ旬報) and Movie Weekly (キネマ週報), promoting the interests of the company. Arriving at their final stop in Japan, the Kawakitas were joined in Moji City by Hayakawa Teizo (早川鐵三), manager of their Fukuoka City branch office. While in Moji, Hayakawa informed the Kawakitas that the primary Towa Shoji movie theater in Shinjuku, Tokyo, had just partnered with the SP Chain. The Musashino-kan (武蔵野館) and the Shochiku-kan (松竹館) had been engaged in a significant cinema battle between two competing theater groups concerning rental fees, ticket prices, and the arrival of sound films from foreign markets.12 During May and June of 1932, several labor union strikes forced closures of theaters in Tokyo and Kansai, including the Musashino-kan.13 For some time, the Kawakitas had arranged their foreign film screenings with the Musashino-kan, and it served as a primary venue for showing German and French films; therefore, when the theaters joined the SP Chain film union, the removal of the tension between the two Tokyo companies would have been significant news for the Kawakitas as they departed Japan.

Shanghai: A Deteriorating Business Scenario

In the early fall of 1929, Towa Shoji established a branch office in Shanghai, managed by Matsumoto Ryu (松本龍). Nagamasa had long been connected with China and was fond of the country and its people, beginning in 1906 when he lived with his family in Hebei Province, where the Baoding Military Academy employed his father for six months. It is beyond the scope of this article to detail his numerous connections to China, including studying abroad and various travels; his experience and fluency in Chinese enabled Kawakita to form many significant business partnerships. Even with his long connection with China, the Kawakitas and Towa Shoji were still Japanese, and after a few days at sea, they arrived in Shanghai on June 6 to meet with Matsumoto, where the anti-Japanese sentiment was palpable. This first meeting would be one of three held during their two-day stay. After hearing Matsumoto’s business report, it quickly became clear that the Chinese boycott of everything Japanese—resulting from the military invasion in Manchuria and the first Battle of Shanghai in early 1932—made it infeasible to continue operations. The outcome of the meeting was that the Kawakitas and Matsumoto agreed the best move was to temporarily close the Shanghai branch office.

The Towa Shoji office was located at 21 Museum Road (now 146 Huqiu Road), Shanghai’s cinema activity hub, in the modern art deco Shahmoon Building. Still standing today, the building designed by C. H. Gonda (1889-1969) has been recognized for its architectural significance by the Chinese government. In 1932, it housed the first air-conditioned movie theater in Shanghai. Film companies such as Ufa, Fox Film, Paramount Pictures, and United Artists had offices on its upper floors. After the luncheon meeting with Matsumoto and a visit to the location of the first Battle of Shanghai, toward evening, the Kawakitas met Alexander Krisel (1890-1983), the representative for United Artists. Krisel had already spent several years in Asia, working as the commissioner of the United States courts in China, before moving to private law practice with his brother. He also held an influential position in the cinema industry, reportedly maintaining control over most of the theaters in Shanghai.14 While based in Shanghai, Krisel was also familiar with Japan and visited Japan with his family. His connection with Kawakita arose through their mutual involvement in the film industry. In 1934, when United Artists had trouble with their management in Japan, Krisel wrote strongly concerning his confidence in Kawakita:

I am still of the opinion that we would be much better off with a Japanese high-class type of businessman in charge of our business in Japan than we ever could hope to be with any American management. Kawakita, in my opinion, has more intelligence, a better education, and is a superior businessman than any American manager in the film business in Japan.15

While the diary is unclear what the Kawakitas and Krisel discussed, considering the fact that the Towa Shoji Shanghai branch would now be closed, their conversation would likely have centered around maintaining indirect connections in China through the cover of the American-based United Artists distribution channels, or possibly the growth of sound projection facilities in Japan.

Following the brief meeting, the Kawakitas were picked up by Sir William “Tony” Keswick (1903-1990) and chauffeured to his house in the Minhang District of western Shanghai. Their association with Keswick signifies some of the political influence the Kawakitas had fostered, as Keswick was closely connected with the Shanghai International Settlement. While Keswick was not directly involved with the cinema industry, maintaining his friendship would be financially beneficial for Towa Shoji. Nagamasa had possibly been introduced to Keswick through Hans Bernstein (b. 1893), who was closely associated with the founders of the Towa Shoji organization.16 Bernstein has not previously been linked with the origins of Towa Shoji; however, the original company registration document, held by the Kawakita Memorial Film Institute (川喜多記念映画文化財団), reveals that his name was included as the signatory for and on behalf of the three European directors, Otto Schacke (1881-1961), André Germain (1882-1971), and Baron Georg Eduard von Stietencron (1888-1974). An employee of Orenstein and Koppel, a large-scale German engineering company selling locomotives, Bernstein was their representative in China.17 It is also possible that Bernstein was the unnamed friend in the diary who, along with Matsumoto, greeted the Kawakitas when they arrived in Shanghai. After dinner with Keswick, the group went to the newly opened Cathay Theatre, which was playing Ronald West’s Corsair (1931). Scheduled to depart the following day, they again met Keswick for breakfast, snapping a photograph together, before once more conversing with Krisel at United Artists. Over the next several weeks, the Kawakitas journeyed halfway around the world, visiting a myriad of cities and locations. Kashiko briefly records events and the wonders witnessed while also praising Pearl S. Buck’s novel, The Good Earth (1931), which she had purchased in Shanghai. In Hong Kong, they watched Walter Summers’s The Flying Fool (1931); in Singapore, they went to The Capitol to view The W Plan (1931), directed by Victor Saville. They visited the Snake Temple in Penang, witnessed elephants bathing in Ceylon (now known as Sri Lanka), saw the pyramids outside Cairo, and traveled through the Suez Canal before arriving in Naples on July 8.

Europe, and Switzerland with the Baron

In 1929, the Japanese soprano Yoshiko Tetsu (鐡能子, 1903-1973) married the successful author, journalist, and fascist activist Antonio Beltramelli (1874-1930), 29 years her senior. Having first met in 1925, their relationship led to marriage a few years later, ending with the death of Antonio in 1930. The widow was left with a significant estate (and debt) in the villa La Sisa in Coccolia, Italy, near the central Apennine Mountains.18 The Kawakitas visited Yoshiko, arriving on July 12 after having climbed Mt. Vesuvius and touring Rome. It is rather unlikely that the Kawakitas knew Yoshiko’s husband, Antonio Beltramelli; however, Yoshiko and Kashiko were friends and appeared in public at art performances in Tokyo.19 Another connection between the Kawakitas and Yoshiko comes through the January 1932 marriage of Yoshiko’s younger sister Mie (鉄美枝) to Aoyama Toshimi (靑山敏美), the director of the advertising department of Towa Shoji. Several years later, both women lived in Kamakura, in Kanagawa Prefecture, an area attractive to people in the arts and art industries. The Beltramelli estate was located just 30 kilometers north of Dovia di Predappio, the birthplace of Mussolini and, subsequently, the gravesite of his mother, Rosa Maltoni (1858-1905). After spending the evening at La Sisa, Yoshiko brought the Kawakitas to Predappio. Considering the political climate of Italy and the triumphant rise to power of Mussolini, along with the proximity of La Sisa to Predappio, it seems clear that Beltramelli’s fascist inclinations left an indelible influence on Yoshiko, enough for her to bring the Kawakitas to Predappio.

Yoshiko Beltramelli singing 'Santa Lucia' (1932).

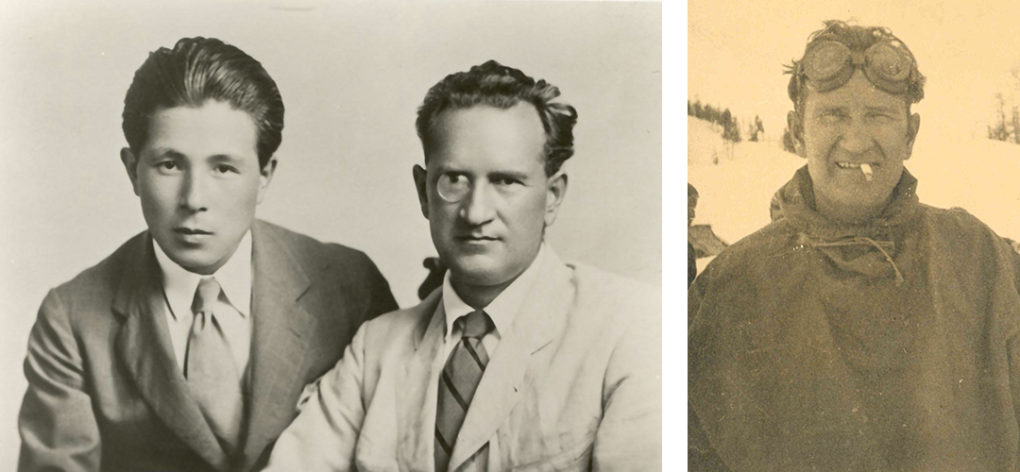

Having departed Italy, the Kawakitas arrived by train in Switzerland on July 15, where they were to be joined by their most intimate European friend, Baron Georg Eduard von Stietencron, of Crissier, Switzerland. The relationship with Stietencron extends back to Nagamasa’s days in Beijing and Shanghai. The two men had been introduced through the aforementioned Hans Bernstein, a business associate of Kawakita’s cousin, Tadayoshi Kawakita (川喜多忠義). Various stories concerning the meeting and friendship between Nagamasa and Stietencron are retold throughout the Towa Shoji commemorative publications, Nagamasa’s “My Resume,” the research of Iris Haukamp and Karl Sierek, as well as Baron von Stietencron’s unpublished autobiography, Lebenserinnerungen (Life Memories). In 1922, the two had met in China when Stietencron needed assistance with antique shopping. Bernstein, a friend of Stietencron from the First World War, connected him to Nagamasa through Tadayoshi Kawakita. Quickly forming a friendship, Stietencron encouraged Kawakita to study in Germany, which he did in 1923-4. Their relationship took a crucial turn to cinema after Baron von Stietencron’s acquaintance, Karl Julius Fritzsche (1883–1954), suggested that von Stietencron pursue exporting European films to Japan.20 Director and producer K. J. Fritzsche, as he was commonly known, was interested in breaking into the Japanese film market for financial and propaganda purposes; later in his career, he would become a critical component of the Nazi agitprop machine as head of Tobis.

Baron von Stietencron was a continually aspiring entrepreneur. If not for his connection with the Kawakitas and the formation of Towa Shoji, his name might have been further lost in time. However, and without a doubt, he is the most unique person in the diary. The visit with Stietencron and the stay at his family home in Ronco sopra Ascona, swimming with the children in the chilly Lago Maggiore, and dining in Ascona before departing from Locarno for Berlin, served as the last honeymoon section of the Kawakita’s European trip. Kashiko paints him as the supreme host of enjoyable evenings and gatherings, a man of great passion and kindness. According to the diary, the Baron had no significant role in their business activities in Berlin during the summer of 1932 and only appeared during friendly gatherings. Nevertheless, the reality of their shared history suggests he was a significant influencer and may have been far more present than recorded. When the Kawakitas and Stietencron met in Locarno on July 15, their reunion would have been joyous—but not due to a lengthy absence. Since the formation of Towa Shoji in 1928, Stietencron and Kawakita met yearly in Berlin, Moscow, and Tokyo to distribute their international films. No exact date or additional proof of their trip to Moscow has been located beyond a brief mention in Stietencron’s unpublished biography.21 In March of 1929, Kawakita returned to Berlin, meeting with Stietencron and bringing several silent films through cooperation with Shochiku (松竹), run by Shiro Kido (城戸四郎, 1894-1977), who would partner with Stietencron to fund the formation of Shochiku Europe Distribution Company (松竹映画欧州配給会社), along with Kido’s cousin, Komakichi Nohara (野原駒吉).22 Stietencron became a free agent for Ufa, forming his own company in May 1929, with film distribution rights for Japan, Korea, Taiwan, and Sakhalin; his contract with Ufa reveals he was in charge of distributing kulturfilme, and he was awarded rights for bringing more than 30 kulturfilme to the East, with the assistance of Hans Fitzke.23 Stietencron again visited Japan in August and once more at the end of 1929. In early 1930, failing health forced him to remain in Switzerland, where he was placed in Ludwig Binswanger’s Sanatorium Bellevue in Kreuzlingen, giving power of attorney over his business to his wife Fides (nee Goesch, 1907-1984), who was briefly assisted by her father, Heinrich Goesch (1880-1930). Stietencron remained in the sanitorium for several months into 1930. However, by summer, he had returned to Japan to continue business only to learn that the entire market had shifted. Writing from the Kawakita’s new residence in Kamakura, he informed Fides that “the entire film situation here is critical. 1) Reduced ticket prices, 2) Sound film crisis, 3) Monopoly of Shochiku, which is financially weak. […]. Therefore, such a splendid and simple business as before is no longer possible.”24 Stietencron’s effort to continue in the film distribution business failed, and due to a series of personal and political difficulties, his firm was bankrupt by May 1932, just a few months before the Kawakitas arrived.25

Disembarking in Berlin

By the time they reached Berlin on the morning of July 19, the Kawakitas were gearing up for an intensive one-month trip around the city, visiting dozens of people, watching more than sixty films, and signing contracts designed to provide Towa Shoji with films for their Japanese audiences. Upon reaching the Potsdam Station on the 07:55 train, the couple were welcomed by Hayashi Bunzaburo (林文三郎, 1906-1997), Ushihara Kiyohiko (牛原虛彥, 1897-1985), and the aforementioned German, Hans Fitzke, whom Kashiko describes as Stietencron’s secretary. In reality, Fitzke was in charge of handling the German side of the Towa Shoji operation. He is an integral—but overlooked and obscure—connection between the Kawakita’s professional relationships in Germany and Towa Shoji in Japan. In March 1930, the Japan Times described Fitzke as a partner “who carries on the business side of the organization” in Germany; referencing Stietencron’s recent Japan visit, the reporter summarized Fitzke’s opinion that the visit had “been productive of much good, and if all plans materialize and Japanese film actors become as well known in Europe as Fritz Lang is in the Far East, it will be greatly due to the efforts of this Baltic Baron.”26 In Germany, Fitzke had been working to facilitate the expansion of the Japanese-German film exchange for at least two years by promoting Towa Shoji.

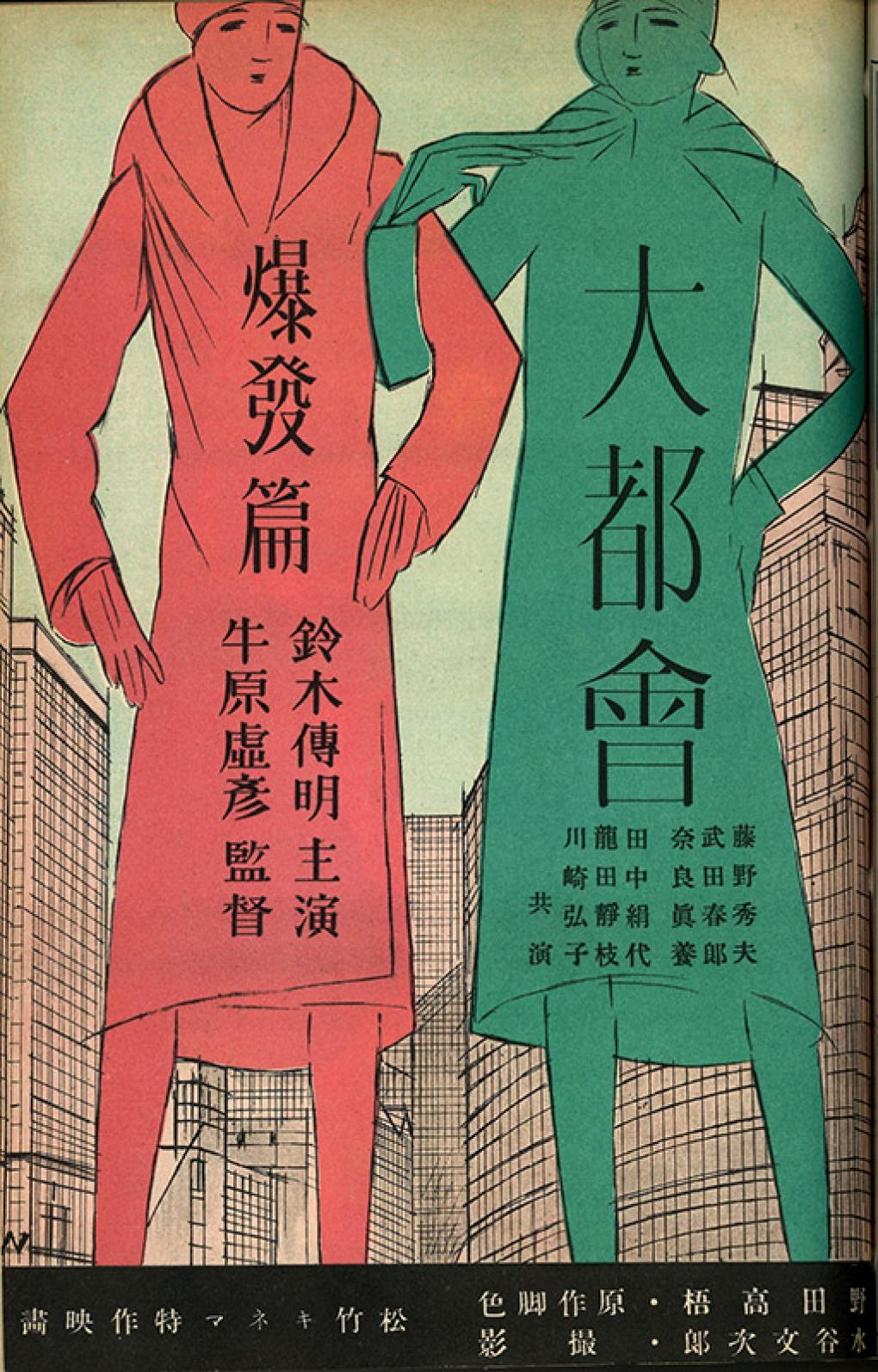

The two Japanese men at the station were important connections for Towa Shoji during this period of growth. Ushihara Kiyohito had been a film director since 1921 with essential links to production studios in Japan, Europe, and the United States, where he had worked under Charlie Chaplin. Before the arrival of the Kawakitas, Ushihara had been in Paris, and on his return to Japan, he passed through Berlin. Already gaining a reputation for film directing, in 1929, he completed the Shochiku film Big City: Chapter on Labor (大都会:労働篇, 1929). Kawakita then brought the silent film to Berlin, where it would be edited with two other films to form the trilogy Nippon (1932). We will return to Nippon later, but Ushihara’s close relationship with the Kawakitas becomes apparent due to his presence in the diary. The third individual waiting on the train platform was Hayashi Bunzaburo, a film critic and resident in Berlin who published numerous articles in the Kinema Junpo concerning German cinema. Hayashi’s educational background was in German literature, having published his first book in 1929, Phantasiestücke aus der deutschen Literatur (獨逸怪奇小説集, [A Collection of Weird German Fiction]); his interest in film began during the transition between silent and sound films, and possessing fluency in German aided his work in the translation of film dialogue, subtitles, and intertitles from German to Japanese, and vice versa.27

Of critical importance was Hayashi’s involvement in the Berlin film scene and his reports published in the Kinema Junpo. During the visit, Hayashi served as the ever-present assistant for the Kawakitas and interpreter for Kashiko. Hayashi would remain in Germany until 1936, and perhaps his most significant contribution to the history of Towa Shoji came in 1934 when he initiated discussions between Dr. Arnold Fanck (1889-1974) and the Kawakitas concerning the joint film production, The Daughter of the Samurai. Hayashi then served as Fanck’s interpreter during the 1936-37 filming in Japan.28 A significant production that joined two aggressive powers of World War II, The Daughter of the Samurai could be viewed as a visualization of Lebensraum (the political justification of land-grabbing undertaken by both Germany and Japan). The idea of a joint German-Japanese film originated as early as the summer of 1932 (see below); however, it took several years before the two film industries collaborated to bring about the story of a cross-cultural romance meshed with the political expansionism of Japan into Manchuria.

Settling into Berlin

After the welcoming, the group of five set off for Wittenbergplatz 3-A, the location of the Towa Shoji office in Berlin’s Schöneberg district. Here, the Kawakitas would establish their home base for their stay in Berlin. Interestingly, the address at Wittenbergplatz had also been where the Shochiku Berlin office was located, and in 1927, the address was linked to a liquidated Hans Fitzke company.29 Kawakita was likely made aware of the location due to the connection between Stietencron and Fitzke.30 In the following sections of the diary, Kashiko records each day in rapid succession, only occasionally providing insight into her thoughts. There are numerous references to movies and their possible reception by Japanese audiences. For concision, we have omitted the vast majority of films viewed and Kashiko’s opinions on each film, providing instead a list in an Appendix of the entire catalog of films recorded in the diary.

Immediately after settling in, the Kawakitas visited the Ufa headquarters in the Krausenhof building on Köthener Strasse, their most significant German supplier. There, they met Gerhard Krone (b. 1901) the new director of the Foreign Affairs Department. A behind-the-scenes man at Ufa, Krone had previously worked in the New York City branch. He eventually rose to the top corporate ranks, reaching managing director in the late 1930s.31 The Kawakitas had hoped to meet with Wilhelm Meydam (b. 1891), the director of domestic and international distribution for Ufa. Since joining the company in 1921 as a sales department correspondent, Meydam had experienced a rapid rise, remaining in a director position and a board member into the 1940s. In January 1931, he was appointed to the board of directors for Ufa and placed in charge of national and international film distribution, replacing Kurt F. Hubert (1888-1945), a personal friend of the Kawakitas. Concurrently, Meydam was in charge of the Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Filmverleiher Deutschlands (Association of German Film Distributors), or AFD, formed in 1929 in an attempt to better organize the distribution of German films, thus making him a key contact for the Kawakitas.32 Along with Meydam, the Kawakitas intended to meet Berthold von Theobald (1882-1947), who had also been appointed in 1931 by Ernst Hugo Correll (1882-1942) to the position of directing manager of Ufa.33 In 1933, to comply with new National Socialist antisemitic regulations, Meydam and von Theobald would serve on the Ufa committee to determine which Ufa employee contracts should be canceled due to Jewish heritage; among those discharged from the company was Erich Pommer (1889-1966).34 Meydam and von Theobald were essential connections for the Kawakitas, as all films they hoped to import to Japan had to be approved by both men who worked under the direction of the corporate president Ludwig Klitzsch (1881-1954). However, the Kawakitas were disappointed that afternoon, as the men were out of the office (likely involved with the Ufa-Convention). They spent the rest of their day embarking on their rigorous film viewing schedule, attending shows at the Ufa Theater am Kurfürstendam and Ufa Palast am Zoo.

They went to the Prinz Albrecht Hotel the following morning, where they met with Meydam and von Theobald. Kashiko does not record anything about the meeting; however, the choice of the Prinz Albrecht Hotel as a meeting place with the Ufa executives should not be overlooked. The hotel was already gaining popularity with the National Socialists, and both Hitler and Joseph Goebbels held meetings and rallies there. The hotel was most likely a convenient gathering place, as it was a central venue for the 1932 three-day Ufa-Convention.35 Later in the morning, they went with Krone and visited Afifa (Aktiengesellschaft für Filmfabrikation), the most prominent film copying laboratory in Europe, under the directorship of Dr. Richard Schmidt (b. 1903). As part of the convention, Afifa had arranged a special guided tour with 300 guests, including the Kawakitas. Kashiko records that they were shown the process of developing and printing film and some of the new dubbing technology that would become significant during the latter part of their trip when they tested dubbing in the Japanese language.

In Pursuit of Film Contracts

July 20 was a seminal day for the Kawakitas and the future of Towa Shoji due to one specific film. After their hectic interactions with the Ufa directors, the visit to Afifa, and reading numerous letters from Japan, they went to the Ufa Pavilion to see Leontine Sagan’s highly acclaimed Mädchen in Uniform (Girls in Uniform,1931), produced by Carl Froelich (1875-1953). Kashiko had been greatly anticipating the film, not least because the director and the cast were entirely female. Across the next several decades of historical retelling of the Towa story, it is with this film that Kashiko established herself as a first-rate connoisseur for selecting movies destined to be successful with Japanese audiences. As the account goes, when they returned from watching Mädchen in Uniform, the husband and wife were at odds concerning its potential for success with Japanese audiences. Kashiko wrote in her diary,

when I saw it, I was surprised at how good it was. As a film, it is comparable to [René] Clair’s À nous la liberté [Freedom Forever,1931]. In literature, it should be compared to Takekurabe [たけくらべ, 1895-96] by Ichiyo [Higuchi, 樋口一葉, 1872-1896]. The fineness of texture. The depth of flavor. I am greatly impressed. I think this film alone would be well received in Japan, but Kawakita has a different opinion.

Nagamasa’s concern centered around an all-woman film directed by a woman that might not sufficiently attract an audience. Decades later, he wrote in his serialized newspaper column, “I was a little uneasy about the praise of ‘a film that only women can make; a film that only women can understand.’” After Kashiko’s opinion prevailed, the success of the film was overwhelming, essentially cementing the status of Towa Shoji throughout Japan. Kawakita later concluded, “since that incident, I have come to respect and trust my wife’s judgment in selecting films. And she has indeed chosen many artistically excellent films.”36 Kawakita was cautious partly because Japanese female actors had only been allowed to star in films starting around 1922 when Nikkatsu hired women to replace the oyama, male actors who played the female roles. Ten years later, a movie with only women, directed by a woman, might have been surprising for more conservative viewers—or perhaps even labeled a “womanly drama” and avoided by the larger public audience.37 Selecting Mädchen in Uniform proved crucial for the Kawakitas as they soon encountered difficulties with their primary provider, Ufa.

Over the next few days, the Kawakitas watched films and were guests at the Ufa summer conference, attended by more than 300 Ufa-affiliated employees and actors. While there, they met numerous people, including president Ludwig Klitzsch, director Erich Pommer, and various actors, such as Conrad Veidt, Willy Fritsch, Renate Muller, Maddy Christian, and Werner Heimann. They gathered in one of the large Ufa studios, converted temporarily into a dining hall, and after, went to the Kammer Lichtspiel theater to watch Hanns Schwarz’s Ihre Hoheit befiehlt (Her Grace Commands, 1931). On July 22, Kashiko again met with Hans Fitzke to discuss the financial situation concerning Towa in Berlin. As noted, Fitzke was responsible for managing Towa’s Berlin accounts. The economic crisis with the Reichsmark and the Japanese yen continued to deteriorate. At one point during the trip, Kashiko writes of her surprise that 1000 yen only converted into 950 marks, thinking, “at this rate, we might have to give up the import business.”38 They were joined on this day at Ufa by a third Japanese man who appeared for a short while among the Japanese coterie surrounding the Kawakitas: Sekizawa Hidetaka (關澤秀隆), a young expatriate who spent ten years in Paris. During his period in and around Montparnasse, Sekizawa was involved with the Japanese community, helping organize and attend dozens of banquets arranged by the Paris Society (巴里会), a Parisian organization of Japanese artists and businessmen. Sekizawa became involved with the theater, playing a few minor roles. He also connected with Albatross Studios and Pathé-Natan, the latter through his friendship with Ushihara Kiyohito during their overlapping period in Paris. Together, Ushihara and Sekizawa had formed a friendship, and when Ushihara left Paris for Berlin, Sekizawa decided to follow for a visit. The newly formed group then dined at Kempinski’s, an elaborate restaurant catering to the entertainment community; they then went to see Der Kongress tanzt (The Congress Dances, 1931) at the Colosseum Theater. The theater manager had attended the Ufa dinner the previous day and noticed the Kawakitas. The identity of the manager is not made clear in the diary and the closest we could ascertain was a Mr. Bock, who in September was transferred to Dortmund and replaced in Berlin by a man named Fritzenwallner.39 Kashiko records that Bock felt compelled to warn the visitors:

When we went to buy tickets, the manager came out and showed us to a special seat. He said he had seen us in Ufa yesterday. He told us to be careful because there are many communists in this area, and Japanese people could be attacked anytime. He was worried when he saw me in my kimono.

Such threats were a reality for the Japanese community in Germany. Before the Kawakitas arrived in Berlin, the Japanese Embassy had been vandalized in January, and in March, a Japanese Vice-Consul had been badly beaten by socialists in Hamburg. The threat to the Japanese in Germany was further exacerbated by Ernst Thälmann (1886-1944), leader of the Communist Party (KPD), who derided Japanese actions in China.40

On Sunday, July 24, along with Ushihara, Sekizawa, and Hayashi, they went to Grünewald Automobil-Verkehrs-und Übungsstraße (Automobile traffic and training road, or AVUS) to watch a 100km speed race with the top cyclists of Europe. The word written in Kashiko’s diary is “オートバイ”, or auto bike; however, after extensive research, there were only two events at the Grünewald Deutsches Stadium on this date: the 100km speed race (on bicycle), and Manfred von Brauchitsch’s attempt at a new speed record in his Mercedes sportscar.41 Visting the Grünewald Stadium, however, is another sign of the political climate of Germany. Due to the recurring radical protests and political uprisings across the country, the Reich’s Minister of the Interior had restricted all public gatherings, limiting them to fence-enclosed ticketed venues. Uniforms, firearms, and explosives were prohibited under penalty of death, according to a June 28 ordinance that went into effect in Berlin on July 18, one day after the Altona Bloody Sunday. Three days after the bicycle event, Hitler would speak at the Grünewald to an audience of 120,000, with 100,000 more listening to loudspeakers at the adjacent AVUS racetrack.42

Several times throughout their visit, Kashiko would visit with Terra-Film A.G., who had provided the distribution rights for a handful of German productions that had proven successful for Towa Shoji. Since May 1929, Terra had been distributing American films for United Artists. The United Artists-Terra connection would have been closely aligned with the Kawakita business connections in Shanghai, directed by Krisel. As the Third Reich gained power over the next decade, Terra would eventually be absorbed by Ufa. However, in 1932, and specifically for the Kawakitas, Terra would remain a valuable resource for distributing German film productions. Several of the Terra films the Kawakitas viewed, however, failed to attract Kashiko’s attention, including Robert Wiene’s Der Andere (The Other, 1930) and two by Harry Piel: Schatten der Unterwelt (Shadows of the Underworld, 1931) and Der Geheimagent (Secret Agent, 1932). One film that did warrant Kashiko’s consideration was Erich Waschneck’s 8 Mädels im Boot (Eight Girls in a Boat, 1932), eventually released in Japan in April 1934.

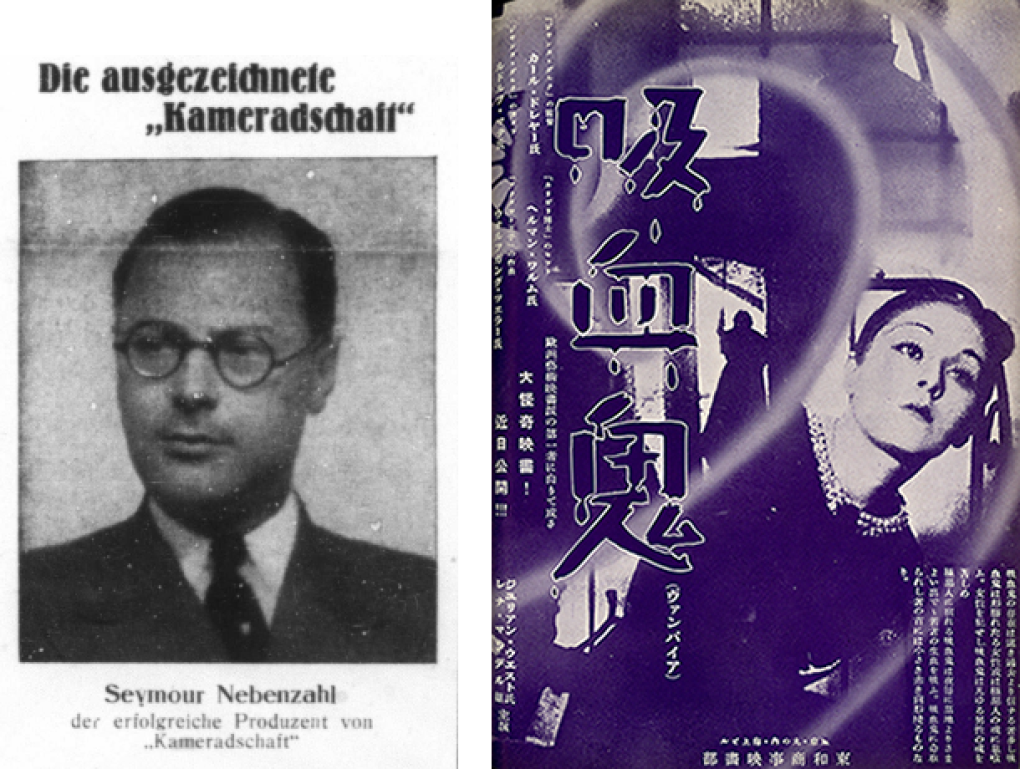

Along with Mädchen in Uniform, two other films hold special prominence in the diary: Carl Theodor Dreyer’s Vampyr (1932) and G. W. Pabst’s L’Atlantide (Queen of Atlantis, 1932), retitled Die Herron von Atlantis, in German. After watching Nippon at Vereinigte Star-Film, they then went to Nero-Film, operated by Seymour Nebenzahl (1899-1961), to watch L’Atlantide, followed by Vampyr at the Metro Palast. Kashiko described Vampyr as a “beautiful and scary picture” and quickly decided it would succeed in Japan. The foreign distribution rights for the film were owned by Conti-Film GmbH, a short-lived distribution company formed on 2 March 1932 for the production, sales, and distribution of films and managed by Alexander Weiß and Friedrich von Kondratowicz, who held contracts with Vereinigte Star-Film.43 On 5 August, the Kawakitas went to Conti-Film to negotiate a contract for Vampyr, which they secured without difficulties and paid the license fee for the film the following day. After viewing Pabst’s Kameradschaft (Comradeship, 1931), Kashiko considered Pabst to be one of the great filmmakers of the era; therefore, the Kawakitas were eager to sign a contract with Nero-Film and Nebenzahl, which they succeeded in doing on July 28. The following day, Kashiko and Hayashi commenced translating the dialog into Japanese.

The Venture into Sound and Dubbing

The objective of the Berlin trip was not to simply secure new films for Japanese audiences. We have mentioned the political climate in Europe; it was also a time of great technological expansion, specifically from silent to sound and the progress in color film processes. While Europe had adapted to this change, one of the primary goals for the Kawakitas was to determine which dubbing and sound systems would best suit the Japanese advancement into the talkie era and then arrange contracts with these companies to assist in providing dubbed films for Japan. Throughout their five-week stay in Berlin, numerous days were allocated to comparing, testing, and even recording on various dubbing and sound systems, ranging from Topoly, and Rhythmonom, to Kinoton. Since they presumed that Vampyr would attract a large audience, the Kawakitas determined that it would be a profitable experiment to dub a section of the film. Kashiko quickly began working on a Japanese script translation to create a sound test with the Topoly system (Tobis-Polyphon-Film GmbH). On August 10, she viewed an English version of Vampyr at the Afifa studio, where they had previously toured the Ufa plant at Tempelhof.

Dubbing sessions for Vampyr were forthcoming, and the French film magazine Pour Vous reported that Japanese students at the Facultés de Berlin would provide voices for the film.44 The film was eventually released in Japan on November 10, shortly after the Kawakitas returned, and received several reviews in the country. However, when reviewing the film, one Japanese film critic who considered the story engaging—even if a bit thematically bizarre in the twentieth century—did not appreciate the Japanese speech additions. Chiyota Shimizu (清水千代太, 1900-1991), a regular reviewer of Towa Shoji imports for the Kinema Junpo felt that “the strength of the film is in its artistic use of light and shadow, and its quality as a silent film.” He goes on to add that the dubbing detracted from the film, as merely a “decorative element,” and Dreyer’s directing to be less successful than that of Pabst in L’Atlantide.45 Another critic for the magazine, Shinbi Iida (飯田心美, 1900-1984), assumed Dreyer was responsible for the Japanese dubbing and criticized the direction of the film since “some errors in handling sound can be felt. One such mistake is the way characters speak, using a method reminiscent of the American talkie style. This approach disrupts the intended rhythm and tone of the film, which should exude a sense of fantasy. The issue of fantasy and dialogue is a challenging problem without easy solutions, yet Dreyer’s approach is less than agreeable.”46 As a first effort in dubbing Japanese for Japan, Vampyr was straddling the silent and sound eras, yet the film ultimately proved successful for Towa Shoji.

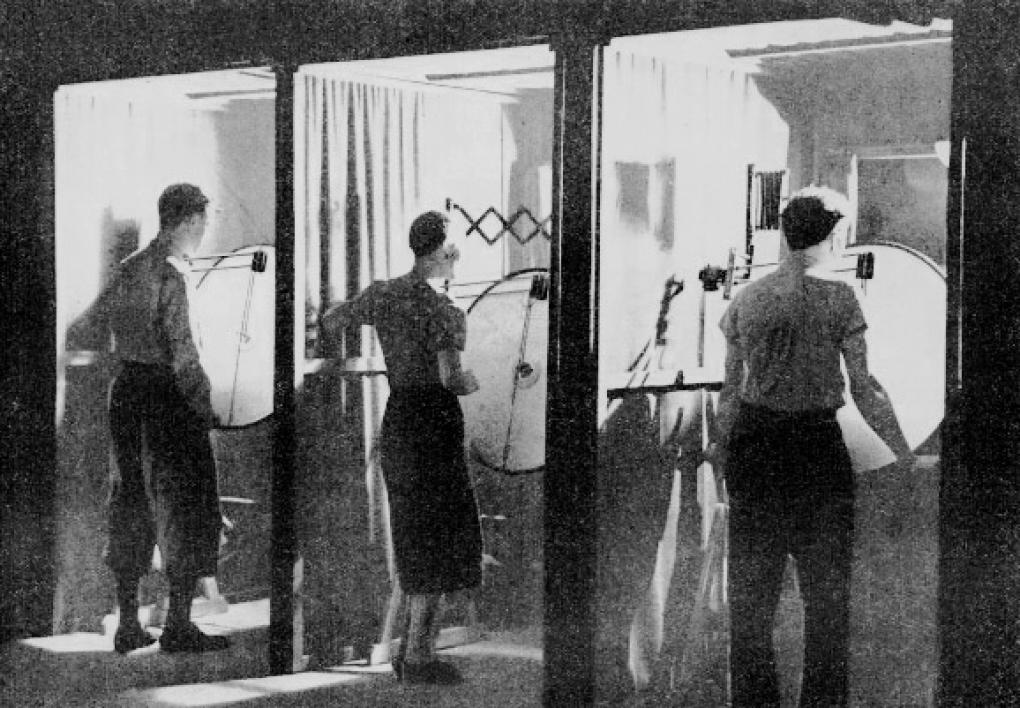

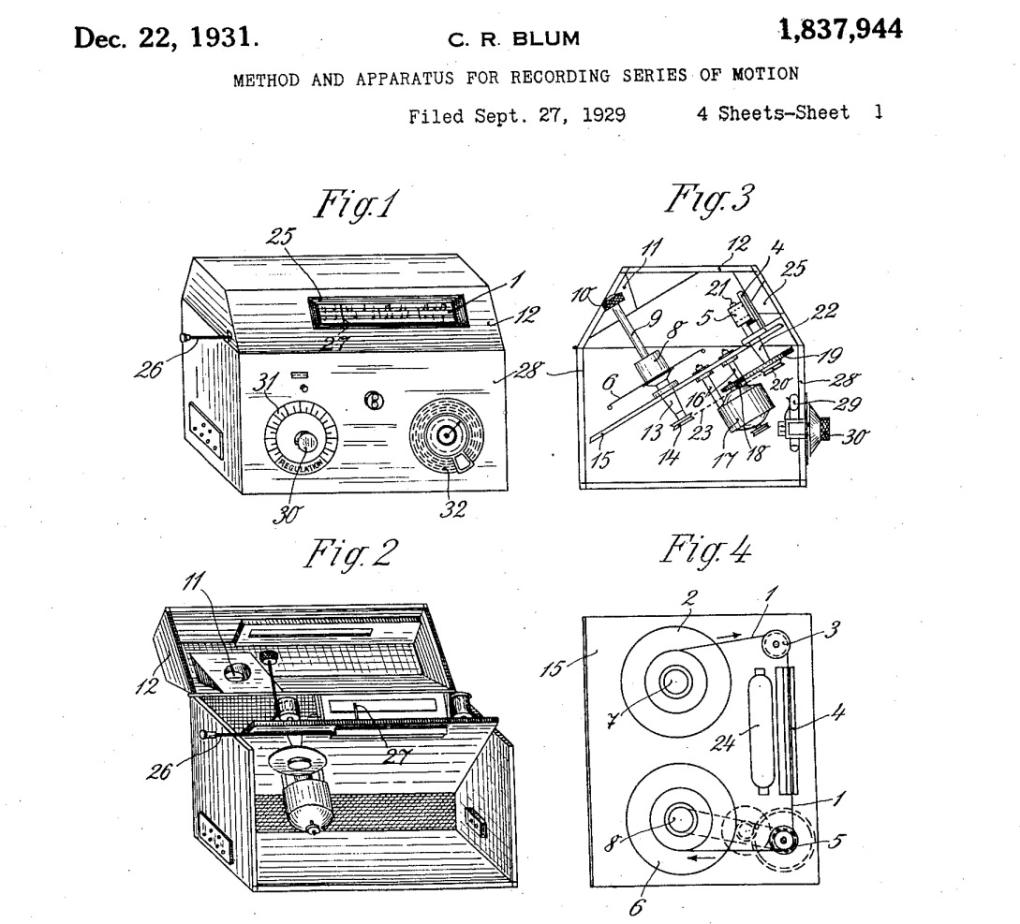

Foreign language versioning becomes a central focus during the latter half of their Berlin trip. In the summer of 1932, Tobis (Tonbild Syndikat) had completed their dubbing studios, in part, to convert foreign films into German language versions. The Society of Motion Picture Engineers reported that Tobis claimed these buildings “to be the most up-to-date and lavishly equipped sound-film studios in Europe [...], in conjunction with Klangfilm, on the site of the Jofa studios. They are now being perfected by the installations of Topoly.”47 Popular Science, without mentioning the Topoly name, featured the system in their November 1932 issue with photographs of “trained linguists” standing in cubicles, where “each actor is guided by a revolving disk marked so as to insure synchronization of sound and action and the right movement of the lips to fit the original picture.”48 In addition to the Topoly dubbing system at the Ufa studios, the Kawakitas also examined Carl Robert Blum’s Rhythmographie system, which had been designed in the mid-1920s, but they considered the functionality far inferior.49

During the afternoon of August 3, Kashiko went with Ernst Jäger (1896-1975), chief editor of Film-Kurier, to view the dubbing machines at the Tobis Ufa studio. It was decided that the Kawakitas would take part in a Japanese test for a section of Wesley Ruggles’s Condemned (1929), starring Ronald Colman and Ann Harding. Nagamasa and Kashiko would assume the leading roles in the experiment, and Kashiko prepared the Japanese script. The event was scheduled for August 9 at the Topoly studio. Condemned served as a dubbing test film for the Topoly system, as the film had received significant press coverage when it was initially dubbed into German the previous April.50 After the experiment, the Lichtbild-Bühne ran an article entitled “Japanese at the Microphone,” in which they gave the following “othered” image of the Kawakitas at work transforming the words of Colman and Harding:

Downstairs in the hall, Nagasama Kawakita and his graceful wife are standing in a booth.

She [Kashiko] is a figurine in a blue kimono with white sandals. She almost disappears under the mighty sash. With their eyes fixed partly on the picture and partly on the dubbing screen, Kawakita and his fragile wife start a melodic chirping that—you cannot believe your eyes—sharply matches the lip movements of the actors on the screen.

[…].

The world in which an American woman plays a French woman with Japanese words conjured up on her lips so that she can be understood […] in Tokyo has become ridiculously small!

By the way, this is the first attempt to dub American and European films into Japanese. If it succeeds—and from what we have seen, there can be little doubt that it will—it will open up highly interesting economic prospects for export to Japan.51

The author’s excitement concerning the positive results reveals the imminent likelihood that the Topoly dubbing technology would greatly expand the distribution of European films throughout Japan. Even Kashiko expressed her surprise with the ability of the Topoly system to synch English and Japanese lip movement: “the Japanese language is so perfectly integrated into the English mouth movements that it is hard to believe that they are not speaking Japanese from the beginning.”52 The experiment succeeded, and the Kawakitas eagerly arranged for dubbed versions.

Guido Bagier and Tobis

Dr. Wilhelm Karl Gerst (1887-1968) ran the Topoly department, and while he is not directly mentioned in the diary, he certainly would have been aware of the project with Condemned. Gerst had recently been appearing at speaking events in Europe with Dr. Guido Bagier (1888-1967). Well-established in the film industry for several years, specifically concerning his interest in the developments surrounding sound film, Bagier had been a valuable patron for the advancement of sound film. Significantly, he had also become good friends with the Kawakitas. He is mentioned several times in a professional function and as an intimate member of a group of people surrounding the Kawakitas, including Baron von Stietencron, Carl Koch, and Lotte Reiniger. Kashiko’s notations of private events and gatherings with these kindred spirits are sprinkled throughout the diary. The Kawakitas were assisted in their interest in dubbing and sound systems for Japanese cinemas through their friendship with Bagier. However, in the diary, Bagier is not linked directly with sound—which had rapidly blossomed by 1932—instead, we learn of his interest in color film. On August 5, Kashiko records a visit to a location she merely refers to as “Bagier’s color film laboratory.”53 It is highly probable that the location was Ufacolor; however, it is also possible that Bagier was involved with Gasparcolor or Sirius-Farben-Film GmbH. Bagier was likely experimenting with color during this period, and in 1933, he would be one of the guest speakers at the third conference for Farbe-Ton-Vorsehung [Color-Sound-Vision], organized by Dr. Georg Ernst Anschütz (1886-1953) with whom Bagier had discussed his research into sound. Anschütz was a psychologist who focused on synaesthesia (seeing shapes while listening to music) and published on color-tone, or the harmony of colors. Thus, Bagier’s early experimentation with color would have appealed to Anschütz’s conference patrons, who had previously convened in October 1930.54

From 1922 to 1927, Bagier worked for Ufa in sound development, and it was likely Bagier who suggested Ufa acquire the rights to the Tri-Ergon system and register a modified patent in January 1925, which briefly came under the directorship of Erich Pommer.55 However, after a dismal sound experiment with Bagier’s December 1925 film Das Mädchen mit den Schwefelhölzern [The Little Match Girl], and then—unconnected—a financial collapse within Ufa in early 1927, the company rejected the sound system by April 1927. Bagier negotiated with the new board director Ludwig Klitsch and took control of the entire Tri-Ergon technical equipment collection, thus assuming control of the now independent Tri-Ergon-Musik.56 For the next year and a half, Bagier improved the Tri-Ergon system, toured Europe to promote sound in film, and published Der Kommende Film (The Coming Film, 1928). In September 1928, a merger with Tri-Ergon-Musik led to the creation of Tobis. Shortly before the Kawakitas arrived in Berlin, Bagier decided to leave Tobis, apparently under amicable terms; however, there was internal strife within the company concerning the exuberant amounts of money Bagier was spending on his film experiments.57 Not surprisingly, Bagier had been preparing to start his own company, TOFA (Tonfilmfabrikations GmbH), probably emulating the similarly named Jofa Workshops at the Ufa branch in Berlin-Johannisthal. In early August 1932, Bagier founded his venture in Berlin, intending to produce and distribute films between Germany, France, and England. Bagier’s corporation would produce a handful of films before disappearing, presumably due to his loss of interest in cinema. In 1933, he would become involved with the Italian producer Giuseppe Domenico Musso (b. 1903) and their short-lived Italian-German company, Interton.58

Bagier’s presence within the Kawakita circle demonstrates the depth of their German film connections and the possibilities for exploiting the rising interest in Japan for German sound cinema. Throughout the German section of the diary, Bagier continually appears; for example, on August 1, they visited his new house in the Dahlemdorf district of Berlin, where they met Jenny Jugo (1904-2001) and her husband Friedrich Enrico Benfer (1905-1996). Jugo would become one of Joseph Goebbels’s most admired German actresses, and her name appears several times in his diaries. The Kawakitas were also acquainted with Bagier’s adopted son, Wolfgang Loë-Bagier (1907-1972), who was working as assistant director on Hanns Schwarz’s Zigeuner der Nacht (Gypsies of the Night, 1932) and had worked with G. W. Pabst on Westfront 1918 (1930). A few years later, Loë-Bagier would assist Hiromasa Nomura (野村浩将) on the second Japanese-Nazi German joint production, Kokumin no Chikai (國民の誓 [Oath of the People], Das Heilige Ziel [The Sacred Goal], 1938). Perhaps the most interesting interaction noted in the diary between the Kawakitas and Bagier occurred on August 8, when along with Carl Koch, the group met at the Hotel Kaiserhof—where Hitler stayed two days before and where, in less than a year later, he would inform Goebbels of his ascension to Chancellor—and discussed the future of German-Japanese cinema. Kashiko records that “a plan is made to produce films between Japan and Germany.”59 In all likelihood, this meeting would be the germination for what would eventually become the previously mentioned first Japanese-Nazi German co-production, The Daughter of the Samurai.

German-Japanese Film Partnerships

Among Bagier’s friends were Carl Koch (1892-1963), husband of the silhouette animator Lotte Reiniger (1899-1981). While it is almost definite that Nagamasa had met them as early as 1928, for Kashiko, her initial interaction with the film couple reveals that the Kawakitas shared a strong bond with Koch and Reiniger. Kashiko first mentions meeting Reiniger at the viewing of Nippon at the Star-Film screening room on July 26; Koch is mentioned on July 29, when they dine with Hayashi Bunzaburo and discuss inviting G. W. Pabst to Japan. The couple was already well known to Kashiko as Towa Shoji had shown Reiniger’s Zehn Minuten Mozart (1930) in Japan during the 1931 film season and Die Abenteuer des Prinzen Achmed (1926), in June 1929. Baron von Stietencron and Hans Fitzke were directly involved with importing Prinzen Achmed to Japan, along with Arnold Fanck’s Das weisse Stadion (銀界征服, The White Stadium, 1928).60 In terms of Koch’s film work, he is often overshadowed by Reiniger’s groundbreaking artistic productions in silhouette film. Before 1932, the pair had spent more than a decade together working on various film projects and organizations, having met as founding board members of Hans Cürlis’s Institut für Kulturforschung (Institute for Cultural Research) in 1919.61 In May 1930, Reiniger and Koch became members of the Liga für Unabhängigen Film (League for Independent Film), formed with, among others, Hans Richter (1888-1976) and Walter Ruttmann (1887-1941).62 Bryher, the editor and writer for the avant-garde film magazine Close Up, describes Koch as someone who knew “a great deal of Japanese culture,” and it is reasonable to presume that Kawakita and Koch met through the large Japanese expatriate community in Berlin. During this period, Germany had the largest Japanese academic community outside of Japan and was ranked third in the number of Japanese living abroad, following France and England.63

![Carl Koch works above Lotte Reiniger in their studio with colleagues (UFA Publicity Photograph) and promotional still from Lotte Reiniger’s '[Prinz] Harlekin' (Vereinigte Star-Film publicity photo).](/sites/default/files/styles/dfi_scale_1020_wysiwyg/public/21-22_2.png?itok=c-ehG8V7)

In the diary, Koch and Reiniger appear in both professional and personal settings, demonstrating the intimacy of their mutual friendship. Having chatted with Koch and Reiniger at Guido Bagier’s house during the evening party on August 1, Kashiko visited Reiniger on August 3. Recording the experience in the diary, she wrote, “I go to Ms. Reiniger’s house to see the process of making a shadow film. It was a challenging job. I was amazed at how a fat lady could do such a tedious job.”64 Due to the Kawakitas, Reiniger’s work was shown in Japan and was reviewed in a January 1929 Kinema Junpo, with photographs credited to Koch.65

Regardless, Koch will be forever tied to the Kawakitas and Towa Shoji through his directorial role of the film Nippon, the first Japanese talkie to be made and premiere in Europe, produced by Towa Shoji and initially distributed by Cürlis’s cultural institute.66 During a previous visit to Germany a few years before, and with the assistance of Baron von Stietencron and Shochiku Shoten, Kawakita arranged for a few Japanese silent films to be brought to Germany to further expose audiences to Japanese culture. With the transition to sound, these silent films essentially became obsolete—not to mention the lack of European interest in full-length Japanese films that tended to portray Japanese culture melodramatically. A plan was designed where three films would be edited by Carl Koch and turned into a culture film about Japan. By 1931, he had been tasked with editing three silent Japanese films into a portmanteau film. Production for the film was credited to Baron von Stietencron, whereas Koch was listed as the Deutsche Bearbeitung und Regie, or German editor and director. Additionally, and likely through his association with Guido Bagier, Koch had successfully dubbed at least two sections of the silent films with Japanese expatriates living in Berlin. In 1930, The Big City, which formed the third section of Nippon, was re-released in a sound version in Japan using the Eastphone sound-on-disc system; it remains unclear if Koch had access to the Eastphone sound discs for the sequences that he reused in Nippon.67

Considering that Nippon was the first production by Towa Shoji, having premiered a few months before they arrived in Berlin, it is surprising that there is only one mention of the film in the diary. On the afternoon of July 26, the Kawakitas went to the screening room at Vereinigte Star-Film. There, they met Lotte Reiniger and Richard Schmidt and viewed Nippon. More than likely, the Kawakitas did not enjoy the overall outcome of the modified films, as Kashiko merely records that “the film is well edited,” giving credit to Koch’s efforts. After returning to Japan, Nagamasa wrote an extended article concerning the production, observing that Koch’s work “depicted an overly vivid image of a belligerent Japan, with bloodthirsty warriors flailing about with swords in their hands,” opinions shared by Ushihara—who attended the viewing with the Kawakitas—in his published critique of the film, “The Problem with the Film Nippon.” Another Japanese critic, who viewed the film in Paris, entitled his review in the Asahi Shimbun: “Watching the Nationally Humiliating Film Nippon.”68 Two significant contemporary sources detailing the creation of the film can be found in Haukamp and Sierek. The silence in the diary is nearly as evident as the published opinions; additionally noteworthy is that Nippon was never shown in Japan, even after being reported in the Film-Kurier that Kawakita intended to premier the film upon his return.69

On August 8, the Kawakitas, and presumably Koch and Reiniger with whom they had just dined at the Japanese restaurant Toyoken, went to the cinema hall Die “Kamera”, Unten der Linden, which was beginning a short run of Reiniger’s Harlekin (1932). Interestingly, Kashiko does not refer to Nippon, which was being shown alongside Harlekin, an omission that infers they chose not to rewatch Koch’s film.70 In 1928, Die “Kamera” and Reiniger made news when Die Abenteuer des Prinzen Achmed was shown after the then-managing theater director Hans Neumann made unapproved edits to the film, prompting Reiniger to vocally protest inside the theater hall at the end of the screening.71 From 1931, Die “Kamera” was briefly under the directorship of Dr. Johannes Eckardt (1887-1966) until February 1932, when he was removed for poor management. Toward the end of Eckardt’s tenure, there were efforts by Erwin van Osen to dub silent culture films accompanied by music from the Wurlitzer organ in the theater, exertions that could not save Eckardt from impending removal.72 The ownership was restored to Emil Wilck and a certain Mr. Dietrich, who were likely still operating the theater when the Kawakitas visited. Whether Eckardt had any direct connection with the Kawakitas remains unclear. He did know Bagier through their 1931 effort to create a German film archive during the same period that Hans Cürlis (1889-1982) was striving to establish a similar library. In 1938, Eckardt helped bring to Germany the Towa Shoji film set in China, Li-Ming (東洋平和の道, The Road to Peace in the East, 1938).73 Along with showing Koch’s Nippon, Die “Kamera” premiered in April 1930 the German version of Kaitô Samimaro (怪盗沙弥磨, 1928), directed by Eiichi Koishi (小石栄一, 1904-1982), released in Germany as Flucht nach Yedo [Escape to Yedo]. This film would eventually form part of Nippon.74 The activity of Die “Kamera” would be greatly impacted by the National Socialists when in April 1934, the president of the Reichsfilmkammer (Reich Chamber of Film, or RFK) ordered the theater closed due to failure to heed warnings concerning the showing of films deemed out of political synch with modern times.75 After its confiscation, the theater was reopened in August 1934 under the control of the Nazi group Kraft durch Freude (Strength Through Joy, or KdF), and in 1935 Die “Kamera” premiered Reiniger’s last German production, Papageno (1935), before Reiniger felt compelled to leave Berlin, moving to London in November.76

Reconnecting with Old Friends

A handful of other key events in the diary concern specific individuals who interacted with the Kawakitas in Berlin. In Japan during the late 1920s, Nagamasa Kawakita had come to know the German Ambassador to Japan, Dr. Wilhelm Solf (1862-1936). Before forming Towa Shoji, Nagamasa’s association with Taguchi Shoten meant he had assisted the short-lived company in signing with Ufa to distribute films in Japan. In November 1927, to commemorate the opening of the Ufa-Taguchi branch, a celebration was held at the Imperial Hotel, with Solf attending as the guest of honor.77 It is likely that Kawakita first met Solf during this event. Having served as a diplomat for eight years in Japan, Solf returned to Germany in 1928 with his wife Johanna (1887-1954) and his three children, including Lagi Solf (1909-1955). During his yearly visits to Berlin, Kawakita worked to strengthen his German ties by fostering a friendship with the Solfs, and during the 1932 trip, they spent time with the former ambassador. The Kawakitas luncheoned at the Solf residence, and Kashiko wrote that Johanna Solf “has a wonderful Japanese kimono that she shows me. She compliments me on my taste in kimonos.” After the takeover of the Nazis in 1933, the Solfs would remain one of the few contacts with whom the Kawakitas would meet on subsequent visits to Europe, as recorded in Kashiko’s later diaries. Significantly, Lagi Solf assisted Carl Koch in the production of Nippon; due to her fluency in Japanese and calligraphic abilities, the creation of the intertitles for the film has been attributed to Solf, and Haukamp suggests that she was one—or several—of the female voices used during the dubbing process.78 On July 29, Kashiko records that she had an enjoyable lunch with Lagi, being joined by Hermann Gundert (1909-1974), the son of Wilhelm Gundert (1880-1971), who was head of the Japanese-German Cultural Institute, located in Hibiya Park, Tokyo, adjacent to the Imperial Palace.79 While living in Japan, Lagi Solf had been the pupil of the German soprano singer Margarete Netke-Löwe (1889-1971), who moved to Japan in 1924 and had recently returned to Germany in March 1932. On their final day in Berlin, the Kawakitas briefly visited with Netke-Löwe.80

The contract between Ufa with Taguchi Shoten began on November 9, 1927, and the subsequent invitation of Wilhelm Solf to the ceremony in Tokyo had both been orchestrated through the efforts of Kurt F. Hubert, the head of foreign sales for Ufa. As Kawakita recalls, Ufa approached him through Hubert, but as Towa Shoji had yet to be established, Taguchi Shoten was chosen as the representative for Japan. Solf’s involvement was fostered through his friendship with Baron von Stietencron, to whom he had been introduced by his friend Hans Bernstein.81 In 1931, when Hubert was replaced at Ufa by Berthold von Theobald, he went on to form his own company in October 1931, Huco-Film-Verwertungs- und Vertriebs.82 Hubert would eventually join Tobis as director of exports in the era of the National Socialists and received mention in Siegfried Krakauer’s From Caligari to Hitler (1947), where Krakauer quoted Hubert as having “labeled the Nazi war film a ‘perfect document of historical truth and nothing but the truth, therefore answering the German demand for a good substantial report in every way.’”83 For the Kawakitas, even after Hubert departed from Ufa, he, and his wife Grace, remained close contacts. During the final stages of their Berlin trip, they shared three meals. The first meeting occurred on August 18, when the two couples dined at a Chinese restaurant. In the diary, Kashiko records a few critical details concerning Hubert’s professional transitions since 1928 (mentioned above); the following day, they met for lunch and then proceeded to Hubert’s factory, where he demonstrated the process of recycling film negatives to remove the silver from old negatives and prints. Afterward, they enjoyed tea at the Hubert residence. On their final day in Berlin, after breakfast with Richard Schmidt, the Kawakitas had their farewell lunch with Hubert and Stietencron, two of their long-term German friends.

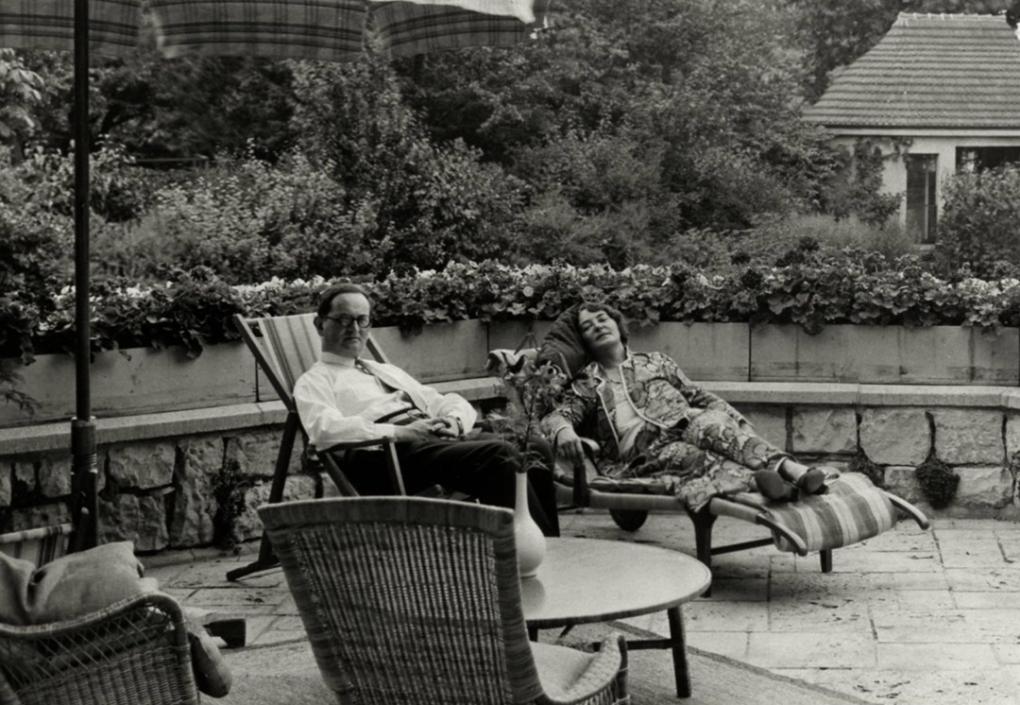

In an almost apropos conclusion, the Germanic part of the diary begins and ends with Baron Georg Eduard von Stietencron. Ever present, yet always at the fringe of their business activities, the Baron remained one of their dearest companions over the five weeks in Berlin. After spending the middle of July with Stietencron in Switzerland, they again joined company on July 31 when visiting his new home in Zehlendorf, near the Grunewald. The date is important, as the national elections were being held throughout Germany, when thirty-eight million Germans (83 percent of the population) turned out to vote, and the event marks the first time in the German Reichstag that the National Socialists gained near-majority results.84 There had been fears that a continued streak of violence would mar the election; however, Kashiko records that the day was quiet, and in the afternoon, they visited Stietencron. Later in the evening, Kashiko read in the newspaper that there were nine murders during the elections. A week later, they spent the day on his boat and joined him again for dinner on August 10. Only once does Stietencron’s connection with Ufa appear when, on August 15, he joins the Kawakitas’ visit to Ufa to likely attempt to solidify negotiations for film contracts (the purpose of their visit is unclear in the diary). On the eve of their August 23 departure from Germany, Stietencron spent the night at their lodging and then joined the luncheon with Hubert. Later in the day they signed a contract with Tobis for Alexis Granowsky’s Die Koffer von Herrn O. F. (The Trunks of Mr. O. F., 1931). Kashiko makes one direct reference to Granowsky after viewing his film Das Lied vom Lebens (The Song of Life, 1931); she simply writes, “Granowsky is changing,” which may be a veiled reference to his willingness to contract his films to Towa Shoji in light of the weak Japanese currency. In 1933, Das Lied vom Leben and Die Koffer von Herrn O. F. were shown in Japan.85 Shortly after finalizing the agreement, the Kawakitas rushed in the Tobis company car to the Berlin Ostbahnhof station, where Stietencron, Hayashi, Okuda, and unnamed others awaited them. The affection between the 45-year-old Stietencron and the Kawakitas is evident in the final moments in Berlin: “The Baron gave me a bouquet of flowers, more than I could hold. [He] held the hands of Kawakita and me and did not let go of them even after the train started moving.” It would be two years before the Kawakitas would return to Berlin to be reunited with Stietencron, and by then, the Nazis had initiated an entirely different film world.

Conclusion

Due to the weakness of the Japanese yen, the Kawakitas left Germany with no Ufa film contracts. This failure meant that the financial lifeline provided over the last four years by the German company was no longer guaranteed. Nevertheless, they secured—directly through the efforts of Kashiko—several sound films that would prove to be phenomenal successes during the early days of talkies in Japan, including Mädchen in Uniform and Vampyr. In total, 21 of the 65 films they viewed during the 1932 Berlin trip were subsequently imported into Japan through Towa Shoji.87 Their trip would encourage the exponential growth of sound-equipped theaters in Japan due in part to their teamwork and shared knowledge acquired in Germany. Within a year or so, Kawakita would resolve the differences with Ufa and restore their contract on a yen-based system, including increased German imports to Japan. The weak yen and the failure to secure Ufa contracts were an impetus for the Kawakitas to begin more seriously looking into the French film market.88 Overall, the trip to Berlin described in Kashiko’s diary, shortly before the ascension of the National Socialists, is filled with individuals and companies that would disappear from Berlin after the rise of Nazi rule. By the time the Kawakitas returned together in 1934, the marketplace had significantly altered. In 1932, the foreboding signs were present in the subtle notes of Kashiko. However, it is easily argued that their visit would firmly establish Towa Shoji as a powerhouse of European cinema imports to Japan, and the unprecedented successes awaiting their film releases would cement their names in Japanese cinema history. If anything, the diary demonstrates how the Kawakitas strategically maneuvered through the unfolding political transitions in Germany—one that threatened certain friends while enhancing the positions of others. Kashiko’s writing is a rare testament of a Japanese woman who had the social and political savvy to pursue the goals of her corporation, thereby bringing unprecedented cinematic experiences to the people of Japan; by 1937, it was reported that Towa Shoji had imported as many as 207 German films into Japan.89

Appendix

Films screened by the Kawakitas during the 1932 trip and referenced in the diary. The year stated is for that of the German release unless otherwise noted.

‘*’ denotes a film later imported by Towa Shoji based on listings in the 1942 and 1955 Towa Shoji publications.

Asia:

Corsair (1931 US) (Shanghai)

The Flying Fool (1931 GB) (Hong Kong)

The W Plan (1930 GB) (Singapore)

Berlin:

8 Mädelsim Boot (1932) *

Abschied [So sind die Menschen] (1930)

Ariane (1931) *

Blue Danube (1932 GB)

Bomben auf Monte Carlo [DE & EN] (1931) *

Condemned! (1929 US) [dubbing test]

Das Flötenkonzert von Sans-souci (1930)

Das Lied einer Nacht (2 viewings) (1932) *

Das Lied vom Leben (1931) *

Das schöne Abenteuer (1932)*- listed as 1939 production,

Der Andere (1930)

Der Feldherrnhügel (1932)

Der Frechdachs (1932)

Der Geheimagent (1932)

Der Hochturist (1931)

Der Kleine Seitensprung (1931)

Der Kongreß tanzt (1931) *

Der sieger (1932) *

Der Tugendkönig [Le Rosier de madame Husson [FR]] (1932)

Die andere Seite (1931)

Die elf Schill’schen Offiziere (1932)

Die Grafin von Monte Cristo (1932)

Die Koffer des Herrn O.F. (1931) *

Die Privatsekretarin (1931)

Die Schlacht von Badamünde (1931)

Die Wasserteufel von Hieflau (1932)

Ein bißchen Liebe für Dich (1932)

Ein toller Einfall (1932)

Einbrecher (1930)

Emil und die Detektive (1931) *

Es wird schon wieder besser... (1932)

Gassenhauer (1931)

Gloria (1931)

Hallo! Hier spricht Berlin! (1932) *

Harlekin (1932)

Hell Divers (1932 US)

Holzapfel weiß alles (1932)

Ihre Hoheit befiehlt (1931) *

Johann Strauß, K.u.K. Hofballmusikdirektor (1932)

Kameradschaft (1931)

Kreuzer Emden (1932)

L’Atlantide [Queen of Atlantis [EN] & Die Herrin von Atlantis [DE]]* (1932)

Mädchen in Uniform (1932) *

Meine Frau, die Hochstaplerin (1931)

Mensch ohne Namen (1932) *

Nie wieder Liebe! (1931) *

Niemandsland (1931) *

Nippon (1932)

One Hour with you (1932 US)

Peter Voß, der Millionendieb (1932)

Quick (1932)

Rasputin (1932)

Ronny (1931) *

Rosenmontag (1930)

Schatten der Unterwelt (1931)

Schuß im Morgengrauen (1932)

Sein Scheidungsgrund (1931)

Stürme der Leidenschaft (1931) *

Teilnehmer antwortet nicht (1932)

Vampyr [EN & DE] (1932) *

Wer nimmt die Liebe ernest? (1931)

Yorck (1931)

Zwei Herzen und ein Schlag (1932)*

Notes

- [return] This research has been supported by a grant from the University of Kitakyushu, President’s Selection Research Grant. We would also like to thank Yukiko Wachi [和地由紀子] and the Kawakita Memorial Film Institute [川喜多記念映画文化財団] for providing invaluable support.

- The diary was published in History of the Towa Corporation: Showa 3 - Showa 17 [東和商事合資会社社史 : 昭和三年-昭和十七年, 1942], and then republished in 2015, as a commemorative edition.

- Kashiko Kawakita [川喜多かしこ], Straight to the Movies [映画ひとすじに] (Japan Book Center [日本図書センター], 1997), 16.

- Kristin Thompson, Exporting Entertainment: America in the World Film Market, 1907-34 (London: BFI, 1985), 142–43.

- Karl Wolffsohn, “German Film Industry at the Beginning of 1933,” The 1933 Film Daily Year Book of Motion Pictures, 1933, 972.

- Komakichi Nohara [野原駒吉], “Die Filmproduktion in Japan [Film Production in Japan],” Neue Zürcher Zeitung [New Zurich Newspaper], September 25, 1932, sec. 4, 13–14.

- “Ideal Film Partnership,” The Japan Times, October 20, 1933, 3.

- Iris Haukamp, A Foreigner’s Cinematic Dream of Japan: Representational Politics and Shadows of War in the Japanese-German Coproduction New Earth (1937) (New York: Bloomsbury, 2020); Karl Sierek, Der lange Arm der Ufa: Filmische Bilderwanderung zwischen Deutschland, Japan und China 1923-1949 (Heidelberg: Springer, 2018); Shojiro Tsuji [辻昭二郎], “「東和商事」と川喜多夫妻の業績 [Towa Shoji and the Accomplishments of the Kawakitas],” 熊本大学総合科目研究報告 [Kumamoto University General Subject Research Report] 3 (2000): 78–86; Kae Ishihara [石原香絵], 日本におけるフィルムアーカイブ活動史 [History of Film Archiving in Japan] (Tokyo: Bigaku Shuppan [美学出版], 2014); Tsuchida Tamaki [土田環], “戦前期の日本映画における「国際性」の概念:『NIPPON』に見る川喜多長政の夢』 [The Concept of Internationality in Prewar Japanese Cinema: Kawakita’s Dream in Nippon],” Cre Biz : クリエイティブ産業におけるビジネス研究 [Business Research in Creative Industries] 7 (2012): 23–50; Yoshiko Yamaguchi and Sakuya Fujiwara, Fragrant Orchid: The Story of My Early Life, trans. Chia-ning Chang (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2015).

- For future scholars, the latter portion of Kashiko’s diary deals with their return journey through war-torn China and should prove to be a valuable first-hand account.

- [return] Kyukanchou [九官鳥], “Cinema Personnel in Japan [映画人國記],” The Kinema Weekly [キネマ週報], February 5, 1932, 21.

- “Kansai Union of Distributors Focus on Permanent Venues [常設館中心の関西配給者聯盟生ろ],” The Movie Weekly [キネマ週報], August 5, 1932, 20.

- History of the Towa Corporation: Showa 3-Showa 17 [東和商事合資会社社史 : 昭和三年―昭和十七年], Japanese Economic Company History [社史で見る日本経済史] 83 (Tokyo: Yumani Shobou [ゆまに書房], 1942), 252; Junichiro Tanaka [田中純一郎], A History of the Development of Japanese Film II: From Silent to Talkies [日本映画発達史 II 無声からトーキーへ] (Tokyo: Chuokoron [中央公論社], 1980), 220–21; Midori Kasugano [春日野綠], “The Current State of the SP Chain [SPチェーンの現状その地],” Kinema Junpo [キネマ旬報], September 1, 1931, 31.

- “Warring Factions Continue to Erupt [爭議相變らず頻々],” Motion Picture Trade Review [国際映画新聞], June 28, 1932, 469.

- “Screen: Items about the Movies,” The Evening Sun, February 27, 1932, 4.

- Alexander Krisel, “Letter to Arthur W. Kelly,” October 12, 1934, Series 9B, Box 2, Folder 5, Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research.