Introduction

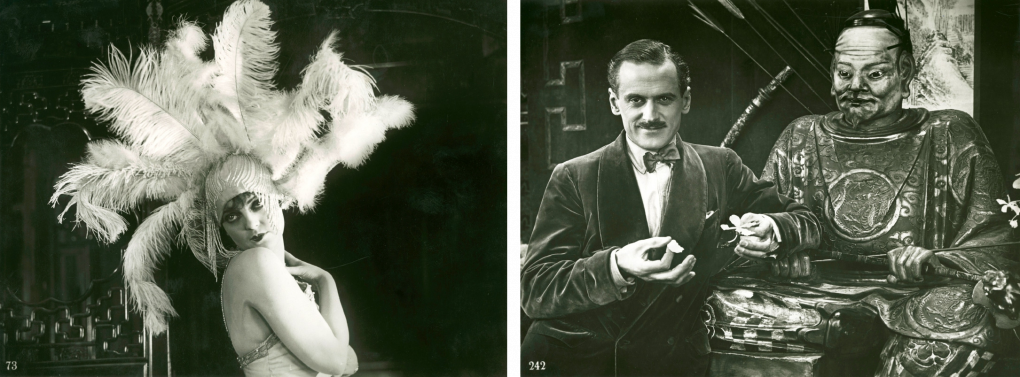

When Hon, den enda (Sparkling Youth, 1926) opened at the cinema Röda Kvarn in Stockholm on November 8, 1926, it was the most highly anticipated film cultural event of the season so far. As a newspaper film critic writing under the pseudonym E–m (1926) explained in Nya Dagligt Allehanda the following afternoon, the film “ha[d] been heralded to usher in a new era in the history of Swedish cinema” 1. In closing of a very positive review, E–m (1926) declared that “[t]here is no doubt that that Swedish film is now on the right course toward future triumphs.” In Stockholms-Tidningen, Robin Hood [Bengt Idestam-Almquist] (1926), arguably the most influential Swedish film critic of his era, had this to say: “Excellent is NOT too strong a word. ‘Hon, den enda’ is really the only one! [The title literally translates as “She, the only one” – author’s note.] The only Swedish film that so far this year has been Film with a capital F. Everything else has been patriotic picture book, fledgling attempts or jokes that fall flat.”

Hon, den enda was the first of seven releases turned out by a short-lived production company called Isepa. Isepa had been incorporated in April 1926, essentially as a subsidiary to Svensk Filmindustri (SF), a vertically integrated film company that was established in 1919 through a merger of Svenska Bio and Skandia, and that operated on a scale that no domestic competitor came even close to matching. Through Isepa, SF set out to develop a distinctly transnational mode of production and a ‘cosmopolitan’ mode of address, with hopes of reviving the enthusiasm for Swedish cinema both at home and abroad. All seven Isepa pictures, released between 1926 and 1928, were Swedish-German co-productions, in three cases with Ufa as the German counterpart to Isepa, and in two cases each with Wengeroff-Film and National-Film as the respective counterpart (credits and production details are from Åhlander, 1982 and Svensk Filmdatabas). In one case – Förseglade läppar (Sealed Lips, 1927) – there was also French money thrown into the mix, via Films Albatros.

Leading roles in these films were mostly reserved for Swedish and German performers, with some notable exceptions. Hans kunglig höghet shinglar ([“His Majesty Bobs His Hair” – author’s translation; no English release title], 1928) starred Chilean actor Enrique Rivero, who was promoted for a brief time as Swedish cinema’s own Rudolph Valentino (Björkin, 1998: 171–93). In Hans engelska fru (Discord, 1927), the Finish Urho Somersalmi was cast to play the male lead against German star Lil Dagover (who also starred in Bara en danserska [Only a Dancing Girl, 1927]). Betty Balfour, a popular British movie actress, played the role of Mizzi in Flickorna Gyurkovics (A Sister of Six, 1926), and British Hollywood émigré Miles Mander played one of the two leading male parts in Parisiskor (Women of Paris, 1928).

All seven Isepa pictures were directed by Swedes – four by Gustaf Molander, one by his brother Olof Molander (pseudonymously credited as Olof Morel), and two by Ragnar Hyltén-Cavallius – but the scripts for six out of seven were penned by an Austrian-born scenario wizard called Paul Merzbach, who had made a name for himself in the German film industry, and who was hired at the behest of Ufa to add the proper cosmopolitan flair to the Isepa pictures and to guarantee that German audience tastes would be met (Vonderau 2007: 205–6).

Aspirations for a cosmopolitan appeal and address informed the choices of locations and settings (London, Berlin, Paris, the French Riviera, picturesquely rural Italy) and the genre orientation (veering mostly toward comedy and romance, although occasionally in more somber directions), and also accounts for a certain emphasis on arguably speculative themes and motifs that would presumably anchor the films in the context of cosmopolitan modernity (night life, fashion, in vogue coiffures, aviation, near-nudity).

Few people outside a small circle of academics, archivists, and silent film aficionados have ever heard of Hon, den enda, or any of the other Isepa films. This indicates a different outcome than SF had hoped for, and a different historical legacy than film critics in the Stockholm newspapers predicted, which is precisely why these films merit historical attention – the Isepa project may not mark an artistic highpoint of silent cinema, but it does stand out as a particularly fascinating failure. For one, it was launched at a moment of crisis for Swedish cinema and hence featured prominently in debates about the identity of Swedish cinema and its position in a thoroughly transnational film culture. Secondly, later on, the Isepa company became a historiographical bête noire, an initiative that film historians argued epitomized, or even caused, Swedish cinema’s demise in the late 1920s. This essay explores both of these sides of the Isepa story, primarily by tracing the reception of the Isepa films through time – from early enthusiasm, through historical neglect and derision, to recent rediscovery and reevaluation. This emphasis on issues of reception and historiography comes at the expense of a close analysis of the films’ style, story, and overall form – such aspects are touched on, but almost exclusively via (oftentimes strongly evaluative) secondary sources, most notably the initial press reactions and later film historical work. To be sure, detailed film analysis opens a highly relevant line of inquiry for my purposes, but one that nevertheless had to be omitted for practical reasons and in order to fully pursue the longer reception history. The same goes for other potential avenues of research, including closer looks into production conditions and practices (for example, a study of Merzbach’s work as a screenwriter might cast interesting light on the discussion concerning the Isepa pictures’ co-articulation of national and cosmopolitan motifs). 2

The essay unfolds in three parts:

- Part one provides a basic historiographical and conceptual framing of Isepa, primarily via a critical unpacking of the idea that the project amounted to an ‘internationalization’ of Swedish silent cinema, following its more strictly nationally oriented ‘golden age.’

- Part two details the contemporary reception of the Isepa films in the newspaper press – especially with respect to the dynamics between national and transnational – and how the Isepa films were framed as a version of national cinema that was different to both the Hollywood model of global cinema and the locally rooted ‘peasant film’ that had previously been perceived to define Swedish cinema.

- Part three maps the historiographical trajectory that followed for the Isepa films, a trajectory that attests to the breakthrough of ‘new film history’ in a Swedish scholarly and archival context, but also to the persistence of the notion of a ‘golden age’ as the historiographical sine qua non for historians of Swedish silent cinema, including those operating within the paradigm of ‘new film history.’

The essay’s analysis of the Isepa project along these lines can be thought of as an attempt to reconfigure the history of Swedish cinema from a lens more sensitive to transnational and global contexts, but the aim is also to make a small contribution to the ongoing excavation of the histories of the serious study of cinema and the formation of cinema studies as an academic discipline – in this case as gleaned from a Swedish horizon.

Part One: A Basic Historical and Conceptual Framing of the Isepa Project

Preambles and Precursors

A cosmopolitan, or de-nationalized, mode of address was not unheard of in Swedish cinema when the first Isepa film was released in 1926. Film historian Rune Waldekranz (1943: 132) wrote that Erotikon (Mauritz Stiller, 1920) provided a model for an “international” film style that he argued was defined primarily by an emphasis on “the fashionable, the witty, and the superficial.” Several decades later, cinema scholars would still point to Erotikon as a possible starting point for the attempts to “internationalize” Swedish cinema in the 1920s (Horak, 2016: 475–6). Another precursor to Isepa that has been subject to recent scholarly interest is Karusellen (The Living Target, Dimitri Buchowetzki, 1923), a picture that foreshadowed the later Isepa releases not only in terms of stylistic and thematic orientation, but also in its mode of production. Although an SF release, and hence arguably a ‘Swedish’ film, Karusellen’s multi-nationally mixed cast and crew barely included any Swedes (the cinematographer Julius Jaenzon is the notable exception). For film historian Leif Furhammar (1982: 16), this indicates that although Karusellen was not the first or only internationally oriented Swedish film from the early 1920s, it went farthest in this direction. More recently, Jan Olsson (2014: 254) has argued along similar lines that Karusellen was, if not the first, then the “most elaborated and daring cosmopolitan endeavor” in Sweden at the time.

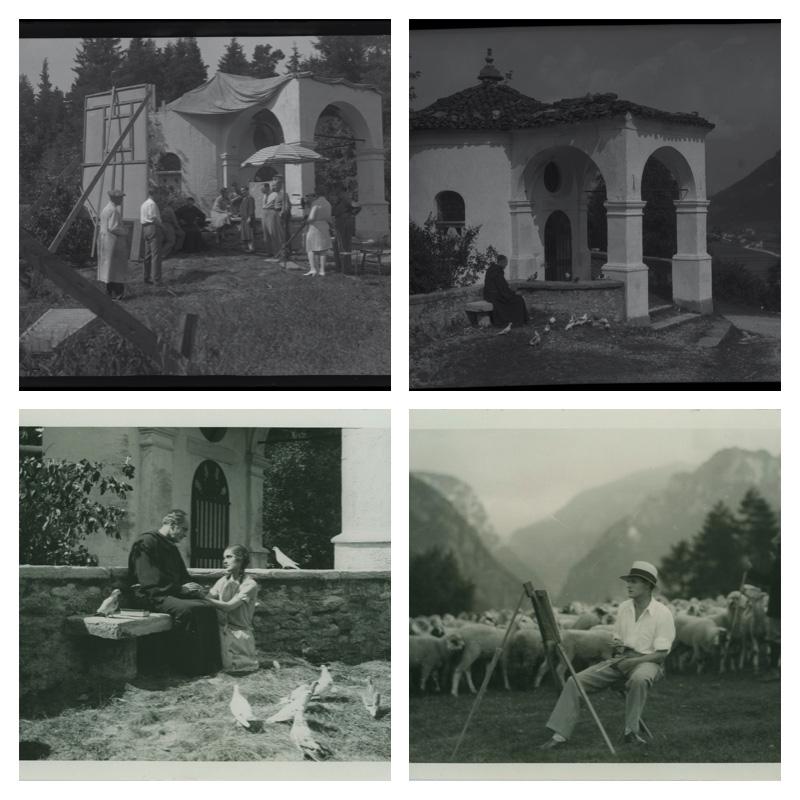

Two other examples that deserve mentioning are Ingmarsarvet (The Ingmar Inheritance, 1925) and Till Österland (To the Orient, 1926) – both directed by Gustaf Molander – a two-part adaptation of Swedish Nobel Laureate Selma Lagerlöf’s Jerusalem novels, also released in two parts (in 1901 and 1902 respectively). Here, the choice of source material links the films to an earlier phase of Swedish silent cinema – the phase that later historians (and some people at the time) would think of as Swedish silent cinema’s ‘great period,’ or its ‘golden age’ – and the cast and crew were predominantly Swedish (with the exception of a few German performers, e.g. Conrad Veidt in Ingmarsarvet). But both pictures were produced by a company called Nord-Westi, a local, SF supported subsidiary of the multinational film corporation Westi, a brainchild of Russian-German film producer Vladimir Wengeroff, financially backed by the German industrial tycoon Hugo Stinnes, and established to contest the American global dominance of film markets and silver screens (Furhammar, 1982: 16). Some critics and historians have suggested that the two Jerusalem films did not match the quality of the best foreign films they competed against – of American or other origin (Idestam-Almquist, 1944: 112). Either way, Nord-Westi was defunct already before its first release. Hugo Stinnes had died in 1924, and within a year, in the midst of production of the two Jerusalem films, his business conglomerate went bankrupt.

The continuation of SF’s experiments in ‘international’ Swedish cinema, and its cooperation with German film interests, came in the form of Isepa in 1926, a project that promised to revitalize Swedish cinema and catapult it toward “future triumphs,” as Stockholms-Tidningen’s film critic E–m (1926) had so boldly proclaimed upon the release of Hon, den enda.

Isepa, The ‘Golden Age,’ and the Concept of National Cinema

It has been de rigueur to think of the examples mentioned above as attempts to ‘internationalize’ Swedish cinema in the 1920s. Without denying the ways in which new balances between the ‘national’ and the ‘international’ were struck, it would be ill-advised to think of the terms as oppositional or indicative of somehow mutually exclusive forces in the formation of Swedish film culture at that juncture (or any juncture, for that matter), or to suggest that the Isepa films or some similar example mark a wholesale historical turning-point when Swedish cinema turned from ‘national’ to ‘international.’ The problem is partly theoretical – decades of critical deconstruction of the notion of national cinema has taught us to recognize the limitations and theoretical weaknesses associated with the concept (many of which are connected to problematic aspects of the more fundamental concepts of the nation and national identity) (for basic orientation in these debates, see Higson, 2000; Elsaesser, 2005b). I will not list such criticisms here, assuming wide familiarity and agreement among my readers.

The pragmatic side of the same issue, on the other hand, merits a few additional remarks, since this provides a relevant background to the reception of the Isepa project as a distinct national-international constellation. First, we may note that only extremely rarely has a film culture existed in pure, splendid, national isolation. And if there are any historical exceptions, Sweden is not one of them. Here, as in most other places, cinema appeared, emerged, and developed as (and remains) a thoroughly transnational – in some sense even global – cultural phenomenon. This holds true also for the presumably national phase that preceded the Isepa films. This era would later become known as the ‘golden age’ of Swedish silent cinema, or alternatively as its ‘great period,’ a historiographical construction that at once designates a period (usually held to have been inaugurated in 1917 with the release of Terje Vigen (A Man There Was, Victor Sjöström) and to have ended in 1924 with Gösta Berlings saga (The Atonement of Gösta Berling, Mauritz Stiller) and the idea of a distinctively national style, characterized primarily by the use of local literary source material and Nordic landscapes, but sometimes also by realism, psychological depth, and other traits that were claimed to be signature trademarks of the period’s two star-directors, Victor Sjöström and Mauritz Stiller.

Perhaps typical of the construction of national cinemas in general, this idea of a national style gained traction (which happened quite early, even as the alleged golden age were still ongoing) at least partly due to the international recognition of it as such (Florin, 1997: chapter 1, especially 42–66), which, in turn, was arguably both an effect and a cause of Swedish cinema’s relative success in world markets during these years. In this regard, the ‘golden age’ clearly exemplifies something that Andrew Higson once argued is constitutive of all national cinemas, i.e. a certain tension between “home” and “away,” between an “inward” look to the national cultural heritage and an outward look “across its borders” through which it asserts its “difference from other national cinemas, proclaiming its sense of otherness” (Higson, 1989, as cited in Higson, 2000: 67). Historically, many national cinemas (not least in Europe) construed of this sense of otherness primarily in terms of contrast, difference or opposition to Hollywood cinema (Elsaesser, 2005a). Indeed, for Kristin Thompson and David Bordwell (1994: 68), Swedish cinema of the late 1910s and early 1920s was the first explicitly national cinema of prominence, but also the first national alternative to Hollywood cinema. The larger point here, however, is that the notion that national cinema is in itself a transnational historical phenomenon, occurring in many places across the world according to a similar pattern, and according to a process that feeds off a dynamic between the national, the transnational, and the global.

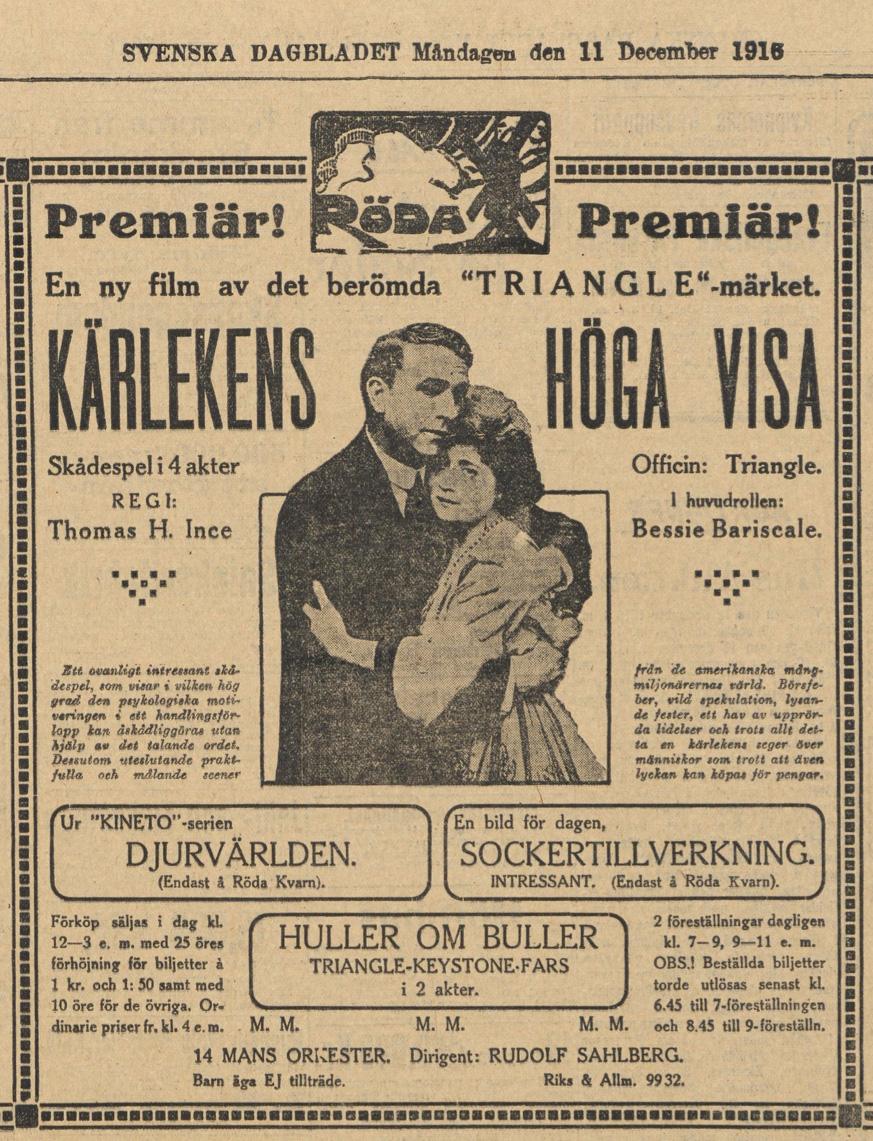

In a later article, Higson (2000) revised and problematized his earlier idea of national cinema as forged through the tension between “home” and “away,” an idea he now sensed bought too much into the notion of culture as a static, fixed entity. In actuality, he argued, both the “home” and “away” of his previous essay are – as all cultural formations – fundamentally hybrid. The case of the ‘golden age’ of Swedish silent cinema serves as an illustration of this idea, too. For example, when Sjöström and Stiller started out as film directors at Swedish Biograph, they adhered closely to Danish and French models, especially those provided by Nordisk and Pathé (Waldekranz, 1985: 481). Both directors are also said to have been quite impressed and inspired by American cinema, first Vitagraph films of the early 1910s, which they perceived to be a more dynamic alternative to French cinema of the period, and later by the lavish Triangle films that reached Swedish movie theaters in 1916 (Idestam-Almquist, 1944: 89–96; Waldekranz, 1985: 533).

Arguably, both of them also learned the ropes of the directorial profession by working with the other, more experienced directors who were brought into the Swedish Biograph studio at Lidingö from 1912 onward from Denmark, France, Germany, the United States, and Russia (Idestam-Almquist, 1968: 167). These people were not hired to teach Sjöström and Stiller to gradually cultivate a national style, but because Swedish Biograph was deliberately targeting export markets, a strategy that also explains why the studio engaged Danish and Norwegian performers with well-established international name recognition, and commissioned scripts from the Danish screenwriters who had helped Danish cinema succeed in the world market (Idestam-Almquist, 1968: 167). Swedish film historians pointed out at least as early as the 1970s that Swedish motion pictures had circulated in world markets long before the advent of the so-called golden age in 1917 (Idestam-Almquist, 1974: 79–82). They also noted (Idestam-Almquist, 1974: 82) that the reason why “quality film” could emerge in Sweden around 1916–1917 was that Swedish Biograph had inaugurated an international film school of sorts at Lidingö, and thus accumulated know-how for years, all with the world market in mind. With that said, we must concede that the singularity of Swedish silent cinema at this juncture resulted when the broadly international style developed by Swedish Biograph merged with locally distinct elements – literary Swedish romanticism of the 1890s; the Swedish landscape; provincial culture (cf. Waldekranz, 1959; Florin, 1997; Florin, 2013: 17–26). But this only reinforces the aforementioned point about the hybridity of cultural formations.

In sum, then, the appearance of the Isepa films did not mark a wholesale historical turning-point when Swedish cinema turned from national to international, but rather a new step in a longer history of Swedish cinema that was already fundamentally transnational. Differently put, what makes the Isepa films historically interesting is not as inaugurators of transnationality in Swedish cinema of the late 1920s, but as key objects of study with respect to the renegotiation of the ‘national’ and ‘international,’ terms that we must approach as historically elastic and variable, not as uniform and fixed. Let us now turn to the critical reception of the Isepa films to explore this last suggestion in more specific terms.

Part Two: The Reception of the Isepa Films in the Newspaper Press

“Swedish International Film”: Discourses on Isepa as National Cinema – Or Not

The ‘international’ profile of the Isepa films, reinforced by SF’s promotion along such lines (e.g. SF, 1926: 13–14), was not lost on contemporary critics. Yet they also made efforts to contain the same films within some category or other of national cinema, framing them as distinctly Swedish. For an illustration, let us look again to E–m’s (1926) review of Hon, den enda, the first Isepa release. For E–m (1926), this picture represented a “new direction for Swedish cinema [my emphasis]” – “European style, yet national.” E–m (1926) also argued that “[t]he era of the Swedish peasant films has passed. … If Swedish film is to live on, if we are to make ourselves relevant out in the world, we must enter new and different paths.” Aftonbladet’s critic R L [Ragnar Lindqvist?] (1926) expressed similar sentiments: “The Swedish peasant films have seen their best days, but this does not mean that the Swedish film with all its distinctive marks and features must perish and disappear from the world market. No, on the contrary, it seems that it is about to enter into a new period of prosperity.” In Folkets Dagblad, an anonymous reviewer raised similar issues, but from a somewhat more critical point of view:

Swedish international film – it is not without an initial degree of skepticism that one approaches this compound term. Doesn’t the Swedishness lose its characteristics and doesn’t on the other hand the internationalism become a bit provincial? These questions should be raised, especially as we have made it a habit to make Swedish film synonymous with peasant film. But why wouldn’t Swedish actors in cooperation with foreign colleagues be able to perform in films with international motifs? (“Hon, den enda”, 1926)

It is significant that the term “peasant film” reappears in several reviews as the key point of reference. The reason, apparently, why many critics initially thought that the Isepa films represented a major turning point in the history of Swedish cinema, and as emblematic of an international reorientation of Swedish cinema, was that they measured them against an earlier cycle of films that were characterized by a more strictly national focus. Most notably, as discussed previously, the so-called “peasant films” were usually adaptations of Swedish (or at least Nordic) literary source material, which anchored them in a homegrown cultural tradition, and they tended to foreground the local natural landscape, which added further to the impression that these films were rooted in uniquely Swedish soil. 3

In other words, the critics picked up on some real and tangible differences between the objects of comparison, so it would be misleading to suggest that the contrast between ‘national’ and ‘international’ was a complete fiction, or an entirely discursive construction. Yet, at the same time, terms such as “Swedish international films” indicate that critics also sensed that a film such as Hon, den enda encompassed multiple dimensions of a more complex cultural geography, where distinctions between ‘national’ and ‘international’ were not very clear-cut, or could only be thought of as a co-dependent conceptual pair.

When Parisiskor, the sixth and penultimate Ispea film, was released in January 1928 many critics in the newspaper press were still convinced that the “Swedish-international” line of production represented a new, brighter and better future for Swedish cinema, and they were still grappling with the issue of how the Isepa films seemed to coarticulate the national and the cosmopolitan. The anonymous critic who reviewed Parisiskor for Folkets Dagblad opened with this statement: “Finally a Swedish film of the highest international standard, captivating from start to finish thanks to an original plot, superior acting, and artistic treatment” (”Margit Manstad i ’Parisiskor’,” 1928). In Nya Dagligt Allehanda, the critic P. J. E. [Per Johan Enström] (1928) declared this “spiritual and elegant Swedish film comedy” a “new victory for the ‘European line’ of Swedish cinema” and a harbinger of even greater accomplishments to come in the next five-ten years. This review also gives us an idea of the crucial role many critics assigned to the Isepa project with regard to the development of Swedish cinema writ large, basically equating the two. According to P. J. E. (1928), “Swedish cinema [had] let go of its national distinctiveness and become European"; or, more succinctly, ”nowadays, Swedish cinema is European.”

Aside from the recurring references to “peasant films” as a general category of comparison, discussions concerning the national specificity of the Isepa films – or lack thereof – often focused on the mode of production, not least details concerning the international composition of the cast and crew. Some critics expressed doubts over whether these films could be considered Swedish at all. For example, the anonymous critic writing for Arbetaren (“Hans engelska fru på Röda Kvarn,” 1927) labeled Hans engelska fru “a Swedish luxury film” but wondered “whether one could call a film that featured two foreign artist in the leading roles” and “a foreigner” as the scenario-writer “Swedish.” In the case of Bara en danserska (1927), Dagens Nyheter’s “critic Jerome [Göran Traung] (1927) simply noted that “the Swedish element was relatively insignificant.” Occasionally, a harsher type of nationalist discourse, usually with an anti-German bent, featured in the reviews of Isepa films, as in Social-Demokraten’s review of Flickorna Gyurkovics (“Många julfilmer,” 1926): “The Germans – with whom co-operation has been established – apparently do not allow for Swedish scenario writers. Deutschland über alles.”

These examples represent a view of national cinema that gives preference to the level of production, but observations about theme, narrative and film style were equally important to how contemporary critics tried to frame the Isepa films as (potentially) distinctly Swedish. Many times, both levels featured into the conceptualizations of national cinema. The reviews of Förseglade läppar offer plenty of illustrations. Arbetaren’s critic pitted the film’s “continental” elements – represented by the German [sic] scenario writer, the Italian setting, and the multi-national cast – against the Swedish element, represented primarily by the Swedish actors who appeared in the film (Review of Förseglade läppar, 1927). For Stockholms Dagblad’s film critic (“Röda Kvarn,” 1927), neither the national origin of the cast and crew nor the setting were necessarily relevant for the film’s claim to Swedishness: “In spite of Paul Merzbach’s German scenario, Förseglade läppar is a Swedish film through and through … you are not fooled for one minute by the Italian setting.” He or she instead argued (“Röda Kvarn,” 1927) that “typical Swedish film art – just like art in general” was characterized by “genuineness, authenticity and composure, and, in addition, a measure of romanticism.” Unfortunately, however, these qualities were oftentimes accompanied by a “heaviness” and a “slow tempo” that were anathema to an art form that required vitality, dynamism, and excitement, the anonymous critic argued.

P. J. E.’s (1927) review in Nya Dagligt Allehanda was more unreservedly positive, and here the point of reference for the film’s merits was not a universalized conception of “art in general” but advances in film art that the writer credited to a group of French filmmakers who had recently “broken ground for the lyricism of cinema” (as opposed to a previously dominant idea of film as an exclusively “epic” art form that provided “exciting drama” structured around “big events”). In P. J. E.’s (1927) opinion, Förseglade läppar had used “the best from recent French productions as the obvious model, this said only to the credit of the Swedish work.” The review implied that American cinema was located at the opposite end of the spectrum. Noting a certain lack of action in Förseglade läppar – “the story could have been told in five minutes in a breakneck American film” – P. J. E. (1927) argued that the film’s strengths resided on another level, and went on to commend the filmmakers’ ambition to hand over an “artistically genuine product.”

Other reviews that featured nationalist discourses were less specific. In Aftonbladet, Refil [Ragnar Lindqvist] (1927) simply stated that Förseglade läppar was a “typical Swedish film with all its characteristics, even though the story takes place entirely on foreign ground,” without going into further detail. Another critic, Folkets Dagblad’s Lei [Hanna Leikel] (1927), framed Swedish cinema with reference to its overall genre orientation, and pointed to its merits as well as limitations as a national cinema: “Swedish cinema has once again proved capable of producing a romantic drama of the highest class [but when] will a director appear who has the capacity to make a Swedish film with social depth, a realistic depiction drawn from life?”

Similar ideas about Swedish cinema and genre featured into the reception of Hans kunglig höghet shinglar – the last Isepa release. Svenska Dagbladet’s Hake [Harald Hansen] (1928b) enjoyed a “brisk tempo” and the fact that the action never came to a standstill – uncharacteristically for Swedish cinema, according to Hake, who concluded that this picture offered “light and pleasant entertainment, which you cannot often say about Swedish film.” Other critics had more mixed feelings. The review in Folkets Dagblad (“Röda Kvarn: Hans kunglig höghet shinglar,” 1928) concluded that Hans kunglig höghet shinglar was “neither fish nor fowl,” describing this film as a “blend of American farce and German comedy, of Swedish … folklustspel [a type of folksy comedy] and Viennese operetta with elements of American revolver juggling.”

Swedish Slowness, American Speed

A particularly widely shared idea in these negotiations concerning Isepa and national specificity was that an essential attribute of the pre-Isepa incarnation of Swedish cinema was its slowness. For instance, Aftonbladet’s anonymous reviewer of Flickorna Gyurkovics wrote that “the action unfolds with a speed unheard of in Swedish cinema” (“Ett glatt lustspel på Röda Kvarn, 1926). In the review of Parisiskor in Svenska Dagbladet, the critic Hake (1928a) praised Gustaf Molander’s directorial skills, evident not least in “the [film’s] tempo, which no longer seems Swedish.” The antithesis to Swedish slowness, these critics argued, was found in the fast-paced American cinema. As Hake (1928a) continued in his review of Parisiskor: “[The filmmakers] really managed to include a bit of the American speediness.” Not everyone agreed with Hake – Dagens Nyheter’s anonymous reviewer found Parisiskor to be “somewhat stretched out” and characterized by an “un-American tranquility” (Review of Parisiskor, 1928) – but the association between American cinema and high-paced action was the same.

Frequently, American cinema was put forth as a general benchmark of excellence, which to some extent was encouraged in SF’s promotional material, for instance by flaunting SF’s studio facilities in Solna as “Råsunda’s Hollywood” (SF, 1927).

With regard to the reception of the Isepa films, Hake’s (1927) review of Hans engelska fru, published in Svenska Dagbladet, argued that the director Gustaf Molander had “stolen from the Americans the tricks that make a film worth seeing.” In Stockholms-Tidningen, Robin Hood (1927) wrote about the same film that the scene in which Lil Dagover’s character trips and rolls down a slope and into a river was “as good as in American cinema, which goes for the rest [of the film], too.” In this case, however, the critic was not talking about the overall artistic quality of the film – over which he had some reservations – but about the director’s technical mastery. In comparison, E–m (1927) in Nya Dagligt Allehanda was more generous both in his appreciation of Hans engelska fru and of American films as a touchstone of technical as well as artistic accomplishment: “It is a film that is fully on par with the best from America.” The anonymous reviewer for Social-Demokraten seemed to agree: “[Hans engelska fru is a] triumph, big enough to compete with the biggest American films of the same genre” (“Hans engelska fru och några andra,” 1927).

In contrast to some of the more overtly denationalized Isepa films, i.e. those more or less fully geared toward ‘cosmopolitan’ themes, plots, and settings, Hans engelska fru is structured around a tension between national and cosmopolitan registers that is more or less literalized in the narrative – the plot centers on the troublesome matrimony between a Swedish landowning forester and a (formerly) wealthy widow from the British upper class – and further reinforced through the film’s shuttling back and forth between high-society London and Norrland (the northernmost part of Sweden). The film’s coarticulation of problems of spatial distance and cultural difference also features a memorable visualization of a radio broadcast that connect the main characters at a crucial point in the story, as well as a fitting setting for the ending – the transitory space of a train station.

Perhaps it was the partial emphasis on provincial, traditional Sweden that led some of the newspaper film critics to point to continuities with an earlier, more locally rooted strand of Swedish cinema. The previously cited review by Hake (1927), for example, did not only point to American cinema as a point of reference for Molander, but also lauded the director’s skillful handling of elements that were “reminiscent of the best days of the Swedish peasant film.“ The anonymous critic writing for Arbetaren seemed to have been generally skeptic about the “foreign” meddling in Swedish cinema that the Isepa line of production represented, but argued that Hans engelska fru managed to “[connect] with the finest Swedish cinematic traditions,” and that the film, in spite of a certain lack of originality, was superior to most American films: “The Americans should see this film, it has a lot to teach them about how to construct a film manuscript. With a few, admittedly brilliant, exceptions, the Americans do not understand that art form” (“Hans engelska fru på Röda Kvarn,” 1927).

For Gvs. [Herbert Grevenius] (1927), writing for Stockholms Dagblad, it was the psychological depth that made Hans engelska fru surpass American cinema: “[Molander’s directing pays] attention to psychological detail [in a way that] gives rise to sincere admiration. How far removed are we not from all the sloppiness, all the hasty decisions and equally hasty changes of heart that the average American film is packed with, and that occasionally are a little too noticeable in the larger productions as well.”

Similar ideas figured into the critical reception of other Isepa films, too. For instance, the review of Parisiskor that appeared in Arbetaren (“’Parisiskor’ (Röda Kvarn,” 1928) also highlighted the technical refinement of American cinema, while simultaneously pointing to its artistic deficits, basically recasting the argument that had appeared in the same newspaper’s review of Hans engelska fru one year earlier: “With regard to technical standards, [Parisiskor] shows that [filmmakers] on this side of the Atlantic has pulled themselves up fully to the level of America – and with regard to intelligence and artistic refinement it has been a long time since they rose above any form of comparison to the average American product.” Other critics shared the premise about American cinema’s technical feats, but did not necessarily draw the conclusion that Swedish filmmakers were on a par. For example, one review of Förseglade läppar complained that the lighting was poor, often rendering the characters obscure in a way that would never happen “in American films that are otherwise very mediocre” (“’Förseglade läppar’,” 1927).

Overall, then, the newspaper press discourse on the Isepa films suggests a view of American cinema as the source of both the most exceptional and the most mediocre films, and as an inescapable object of comparison, especially with regard to a technical excellence that many critics held to be a hallmark even of otherwise second-rate American films. Hypothetically, this pattern is representative of a more widely shared discursive framing of American cinema in Sweden at this juncture in the late 1920s.

Isepa: A Local Response to Global Hollywood?

Discursive framings aside, one of the motivations behind the Isepa project was clearly to compete with American cinema. An interview with Olof Morel (Olof Molander), apparently carried out on location in Berlin in conjunction with the shooting of his Bara en danserska, suggested that Morel wanted to “strike another blow for Swedish cinema’s glorious position on the film market,” and that “Sweden’s help was required when it comes to creating a counter-weight to America’s desire to be the sole ruler of film markets” (Marcus 1926: 433). In this context, the Isepa releases represented an alternative to Hollywood cinema as well as the Swedish peasant films of yore.

A very similar tripartite model had informed the reception of some of the cosmopolitan experiments that had been carried out in the Swedish film industry a few years earlier, as discussed in Jan Olsson’s (2014) intricate analysis of how local productions strategies, changing audience preferences, and discursive negotiations concerning the identity of Swedish cinema interconnected circa 1923 – all against the wider backdrop of the “ubiquitous presence” and “overwhelming dominance” of Hollywood cinema. Olsson (2014: 250) notes that by the early 1920s, Swedish film producers were facing new, and less favorable, market conditions, which he connects partly to the post-war resurgence of motion picture production in France, England, and Germany, partly to the deluge of U.S. film imports.

With regard to the influx of American movies to Sweden, the peak year appears to have been 1919, when 557 of the 692 feature films cleared for release were of American origin (i.e. just over 80 percent) (the figures are from Björk, 1995: 248–9 and Florin 1997: 198, both of which draw on the filmographies compiled by Wredlund and Lindfors, 1979–2002 – a significant index of American cinema’s presence in Sweden, yet obviously only a starting point for more in-depth research into screen dominance). The next largest share of the imports, representing only 7 percent, came from Germany; the Swedish share of the domestic market measure in this way was 2 percent (Björk 1995: 248). In comparison, in 1913, only 4 percent of feature films came from the U.S. and 31 percent from Germany (5 percent were domestic productions) (Björk 1995: 248). The rapid rise of American imports during the war correlates more or less perfectly with the decline of imports from Denmark, England, France, Germany, Italy, and Russia/the Soviet Union (Florin 1997: 198).

In spite of the resurrection of film production in Europe after World War I, American cinema maintained its dominant position in Swedish film markets in the following years (and up to the present moment), with fundamental, lasting, and direct effects on the Swedish motion picture business and Swedish film culture. Moreover, the pattern was quite similar elsewhere, which compounded the problems for Swedish film producers – as an increasingly larger part of the world gained access to an abundance of American motion pictures, the export market for Swedish cinema dried up. According to Bengt Idestam-Almquist (1968: 174–6), the off-loading in Europe of the oversupply that the American film industry generated was but one of several factors that stacked the deck against Swedish cinema around the same time; others included a gradual depletion of capital, inspiration, and international interest in Swedish cinema as other film nations began to catch up artistically.

The overwhelming screen dominance of American movies more or less all over Europe (except, perhaps, for a while, in Germany) from World War I onward is well documented by scholars, as are the discourses and cultural negotiations this gave rise to, many of which expressed fears that the United States was colonizing Europe via cinema – economically, culturally, and ideologically (some of the key contributions – including both economic and cultural histories as well as national case studies – are Thompson 1985; Jarvie 1992; Saunders 1994; Vasey 1997; Higson and Maltby 1999a; Ulff-Möller 2001; Trumpbour 2002; de Grazia 2005; Maltby and Stokes 2004; Glancy 2006; Bakker 2008).

We also know that the global rise of what became known in film industry circles as ‘Film America’ prompted a response in the form of ‘Film Europe.’ As an idea, ‘Film Europe’, in the words of Higson and Maltby (1999b: 2), basically expressed “the ideal of a vibrant pan-European cinema industry […] in a position to challenge American distributors for control of [the European motion picture] market.” As an actual movement, however, it lacked the coherency and central coordination to generate more than “limited, contingent, and fragile” forms of cooperation (Higson and Maltby 1999b: 4). In other words, if ‘Film America’ was the result of a deliberate, carefully orchestrated and bureaucratically coordinated effort – or at the very least a rather well organized effort – to cover the world with American films and American consumer goods, the counter-hegemonic ‘Film Europe’ movement was “a much more fragmented, piecemeal series of enterprises,” as Higson and Maltby (1999b: 4) put it.

According to Higson and Maltby (1999b: 3), such enterprises included “the development of international co-productions, the use of international production teams and casts for otherwise nationally based productions and the exploitation of international settings, themes and storylines in such films.” Laura Horak (2016: 476) is right to suggest, then, that the Isepa films and other similar co-productions made in Sweden in the 1920s make up a forgotten part of the Film Europe movement. Of course, there was also the more explicit Swedish participation in the movement through the ill-fated Nord-Westi project mentioned in the essay’s first part. And Jan Olsson (2014: 249-250) is equally right to suggest that the move toward a cosmopolitan mode of production in Swedish silent cinema that started around 1922 and culminated with Isepa should be thought of as a local response to Hollywood’s dominance.

SF’s efforts to compete with “Hollywood’s screen modernity,” as Olsson (2014: 249) puts it, unleashed a re-negotiation of the concept of Swedish cinema. The title of Olsson’s essay – “Cosmopolitan Skin vs. National Soul” – summarizes a discursive pattern that followed a binary logic that pitted the cosmopolitan, allegedly superficial, and oftentimes comedic register against the spiritual, national drama of cultural depth.

Similarly, the idea of “soul” became a marker of national otherness in comparison to the supposedly crass commercialism of Hollywood cinema (Olsson 2014: 245). On the other hand, as Olsson (2014: 265) shows, there were also those who regarded the “peasant culture onscreen” version of Swedish cinema as an outdated purveyor of Swedishness as provincialism, and as quite anathema to the international, border-shattering film medium, best represented “by the young and vigorous American culture unshackled by stifling traditions and national pride.” Such contrasting views informed the reception of SF’s cosmopolitan test film Karusellen in 1923, perceived by some as an-Swedish and soulless, and by others as profound reflection on modernity and a masterful adoption of advanced American modes of filmmaking (Olsson 2014: 256–8).

Olsson (2014: 254) points out that the larger historical context for the move from peasant films to a cosmopolitan mode of production and address was Sweden’s transformation from an agrarian society to an increasingly urban and industrialized nation. Similarly, in their discussion concerning the ‘international’ films that resulted from the ‘Film Europe’ movement, Higson and Maltby (1999b: 20) argue that a broad distinction between “metropolitan and provincial cultures" was evident in Europe as well as the United States at this juncture, a distinction that generally defined film culture but which, in turn, was to some degree destabilized by the various specific strands that developed within film culture. According to Higson and Maltby (1999b: 20), the European international films of the 1920s offered an “alternative metropolitan modernism,” different from both the Hollywood version of screen modernity it was meant to compete against and provincially rooted models of national cinema. This “alternative metropolitan modernism” overlaps roughly with what Olsson (2014: 265) refers to as “homegrown cosmopolitanism” – an emulation of Hollywood cinema with a European touch.

We have arrived, then, at three main points of reference for the discursive re-negotiation concerning Swedish cinema as well as redirecting of production strategies within SF during the 1920s, both of which culminated with the Isepa project in 1926–1928: (a) Swedishness as provincialism; the peasant film tradition; (b) Hollywood screen modernity; and (c) alternative metropolitan modernism; homegrown cosmopolitanism.

Part Three: Isepa and the Historiography of Swedish Silent Cinema

A Historiographic Bête Noire? Isepa and Sweden’s Foundational Film Historians

Hopes that the international co-production model that Isepa epitomized would usher in a new golden age of Swedish cinema were soon abandoned, and whatever critical esteem the Isepa films had acquired upon initial release also evaporated quite quickly. Consider the case of Bengt Idestam-Almquist, who had exclaimed with such force and conviction in 1926 that Hon, den enda was the only truly outstanding Swedish film of the year, but who later wrote (1944: 116) that the same film – notwithstanding “some merits” – gave off “an insipid taste of artificiality and feigned elegance.”

Idestam-Almquist’s change of heart was evident already by 1929. His review (signed with his usual pseudonym Robin Hood) of Hjärtats triumf (The Triumph of the Heart, 1929) is a case in point. This film was written by Paul Merzbach and directed by Gustaf Molander – two key figures in the Isepa project – and was also reminiscent of Isepa in that it was an international co-production, albeit Swedish-British, not Swedish-German. According to Idestam-Almquist (Robin Hood, 1929), not a single person who attended the preview screening of Hjärtats triumf raised their hands to applaud the film. “Why? This is easy to see. First of all, the film is not Swedish. … Merzbach is left to his own devices, and he is so vulgarly German [äppeltysk] as only the Swiss can be. Accordingly, all talk about a Swedish renaissance for Sweden’s cinema becomes pure nonsense.” 4

Idestam-Almquist did not make a case for return to the good old days, however, arguing that SF would be equally misdirected if they were to “slavishly hang on Stiller and Sjöström, the bigwigs of Swedish cinema’s great era.” The future, he suggested, could instead be glimpsed in the “modern” work of directors such as Murnau, Eisenstein, Pudovkin, and Fejos.

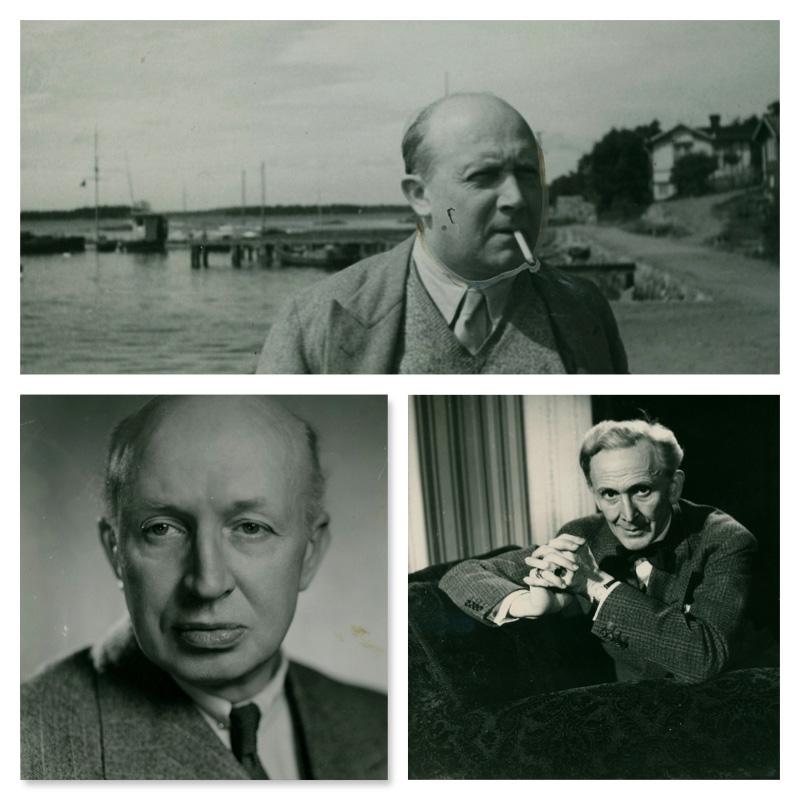

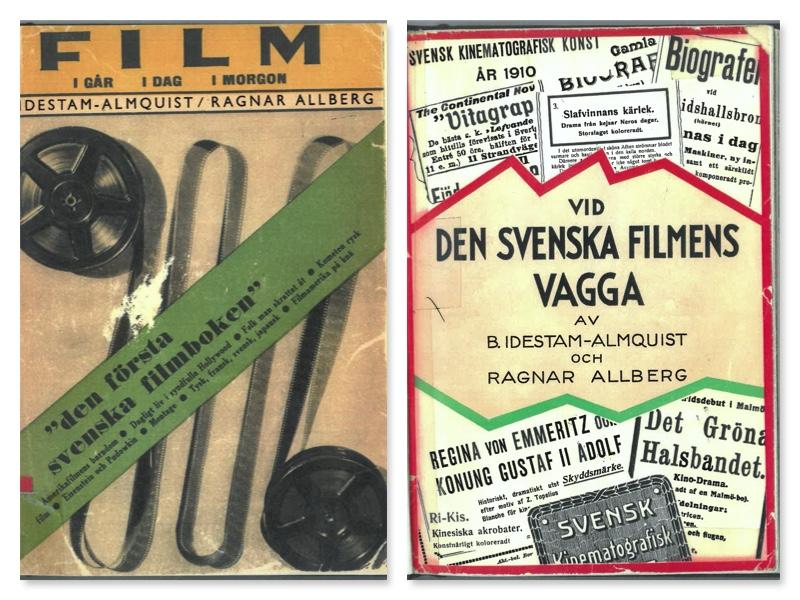

Idestam-Almquist’s review includes several motifs that would inform the historical approach to Isepa and Swedish cinema of the late 1920s for decades to come: nationalist elements; a historiographical investment in the notion of a ‘great era’ of Swedish silent cinema; and an impulse to identify the ‘great era’ with two outstanding directors – Victor Sjöström and Mauritz Stiller. This is not all that surprising given the fact that Idestam-Almquist was not only the leading film critic of his era, but can also be considered the founding father of Swedish film historiography, or, at the very least, a towering figure in the first wave of critics and writers who set out to deal seriously with the history of the motion picture medium in a Swedish context, and who furthermore had a considerable influence on international historians’ view of the ‘golden age,’ as some of his work was published in English and French (Florin, 1997: 13). Together with Ragnar Allberg, he penned Vid den svenska filmens vagga (“At the Cradle of Swedish Cinema”), published in 1936 and the first book-length survey history of Swedish silent cinema. The same pair of authors had also produced Film i går, i dag, i morgon (“Film Yesterday, Today, Tomorrow”), tagged as “the first Swedish film book” when it came out in 1932.

Both volumes gave short shrift to the cycle of Isepa films. The book from 1932 provides this extremely condensed summary of events: “Svensk Filmindustri bravely struggled on in spite of many unfulfilled expectations. The company ‘Isepa’ was established with Oscar Hemberg as head of production, and the firm’s output was internationally produced. The attempt did not turn out happily” (Idestam-Almquist and Allberg, 1932: 136). The 1936 survey history is almost as terse, and adds nothing substantial; Idestam-Almquist and Allberg (1936: 163) conclude that “the Isepa company tried with internationally oriented manuscripts, and Argentinians and Englishmen were cast in the leading roles. But they proved to have little viability.” Neither of the two books provides room for further detail, or even for the titles of any of the Isepa films.

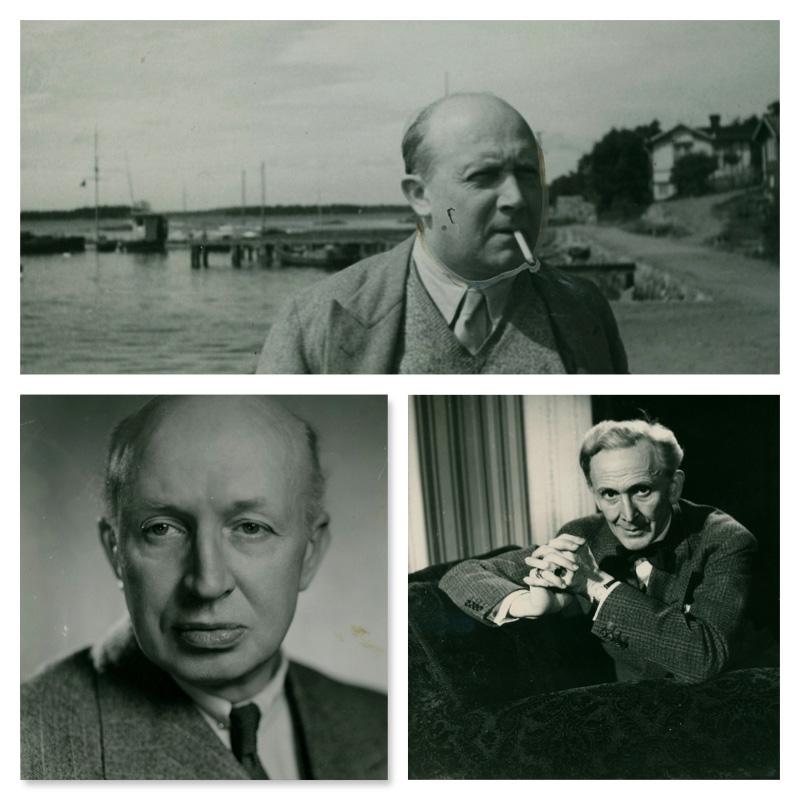

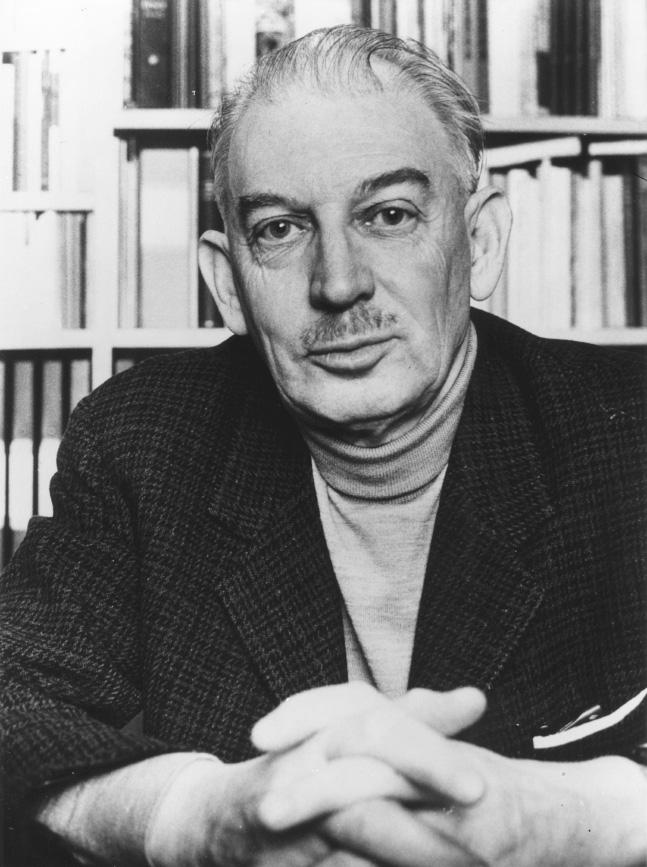

Over the next decade or so, the historiographical agenda shifted from neglect to derision, as indicated in Idestam-Almquist’s retrospective condemnation of Hon, den enda cited earlier. Further illustrations can be found in the early writings of Rune Waldekranz, another pioneering historian of Swedish silent cinema, whose copious work as a film critic, film producer and occasional screenwriter at the Sandrew studio, and film historian with numerous books on a variety of aspects of cinema to his name paved the way for his appointment as the first Professor of Cinema Studies at Stockholm University (and hence in Sweden) in 1970.

His 1941 volume Filmen växer upp: femtio års utveckling (“Cinema Grows Up: Fifty Years of Development”) built on Idestam-Almquist and Allberg’s work, but also on a wide selection of non-Swedish secondary sources, such as Lewis Jacobs’s The Rise of the American Film and Bardèche and Brassilach’s Histoire du cinéma, and relied (mostly) on trade papers for primary documentation – it was meant to provide the first truly comprehensive and rigorously researched introduction to cinema for a Swedish readership. Its discourse on the international orientation of Swedish cinema in the 1920s (a trajectory that Waldekranz (1941: 89–90; 293) argues started during the first half of the decade, well before Isepa) is negative, evident in recurring associations of the “international” with “shallowness” and “artificiality.” A degree of nationalism also comes into play – Waldekranz (1941: 293) describes the Isepa films as an “artificial” product that is “no more Swedish than a sèvre vase,” and as emblematic of the rootlessness of Swedish cinema of the late 1920s. Variations on the same theme resound in Waldekranz’s Den svenska filmen: från kinematografi till filmkonst (“Swedish Film: From Cinematography to Film Art”), a brief overview of Swedish film history published in 1943. Here, too, the films that were designed to target an international audience were characterized as “shallow” and generally bereft of artistic value, and they were again connected to a process of de-nationalization, which Waldekranz (1943: 132) illustrated with reference to costume design: “The good old folk costumes were swiftly replaced by tailor-made tail-coats.” Waldekranz did not soften up as the years went by. In part two of his monumental three-volume Filmens historia: de första hundra åren: från zoopraxiscope till video (“The History of Cinema: The First One Hundred Years: From Zoopraxiscope to Video”), published in 1986, he argues that the Swedish-German coproduction venture of the late 1920s was “fatal,” and he describes the resulting films as derivative, flaccid, flat, and full of cinematic platitudes (1986: 426–33).

Similar to the newspaper critics who had first reviewed the Isepa films, both Idestam-Almquist and Waldekranz set up a metonymical relationship between internationally oriented films à la Isepa and the development of Swedish cinema writ large. Logically, then, they concluded that Swedish cinema ended up in a state of disrepair in the late 1920s. Idestam-Almquist (1944: 85–6; 116–8) suggested that Swedish cinema had traveled back in time, regressing to an art-less stage – the landmark achievements of master film artists such as Sjöström and Stiller had not completely disappeared, but were only visible on a purely technical, non-artistic level. Waldekranz, meanwhile, wrote around the same time in the early 1940s that what followed after Sjöström and Stiller had left Sweden was a faint “reverberation” (efterklang). The same term was later used by Gösta Werner (1970) to designate what he regarded as the third and final period of Swedish silent cinema.

Werner was another trailblazing figure in the serious study of cinema in Sweden, involved in numerous film cultural initiatives from as early on as the 1920s, and whose multi-decade track record as a filmmaker (mostly short films, some of which are considered classics of Swedish cinema) as well as a critic and historian of the film medium (with broad expertise, but with Swedish silent cinema – the films and career of Mauritz Stiller in particular – as a special research interest) eventually earned him the title, if not the chair, Professor of Cinema Studies at Stockholm University (for a career history, see Stjernholm, 2018). As already indicated, Werner did not look kindly upon Swedish cinema of the late 1920s, especially as compared to the halcyon days of Sjöström and Stiller. In Den svenska filmens historia: en översikt (“The History of Swedish Cinema: A Survey”), Werner (1970: 47) wrote that the final years of Swedish silent cinema was “one, long, bitter reverberation of the second period [of Swedish silent cinema] and its great, stylistically groundbreaking works.” In his view (1970: 47; 50), the internationally customized productions of the late 1920s represented “a series of desperate attempts” by SF to capture a greater share of the foreign market – an understandable, but ultimately futile ambition. With regard to the films themselves, Werner (1970: 50) notes that they were often well-staged and featured good performances, but that they were either boring, heavy, pretentious, or indifferent, and that they generally lacked edge, substance, and a properly cinematic narration.

Werner’s tripartition of Swedish cinema’s silent era into a relatively primitive phase, a golden age, and a period of “bitter reverberation,” was basically retained in the next major survey history of Swedish cinema, written by Leif Furhammar, who had become Sweden’s second Professor of Cinema Studies when he replaced Waldekranz in 1978. His Filmen i Sverige: En historia i tio kapitel was first published in 1991, followed by a reissue in 1993 and updated editions in 1998 and 2003, and became a standard reference and a widely used textbook in film history classes across Sweden. In it, the preferred term to describe the late 1920s was not “reverberation,” but “decadence.” Indeed, “Dekadens: svensk film 1925–1930” [“Decadence: Swedish Cinema 1925–1930”] was the title of an earlier, unpublished paper that Furhammar had written at Stockholm University’s Department for Theatre and Cinema Arts (subsequently the Department of Cinema Studies and presently the Department of Media Studies, which harbors a Section for Cinema Studies), probably in 1980, and that provided much of the raw material as well as final text of the later survey history’s discussion about the sunset phase of Swedish silent cinema. The following quote from “Dekadens” (1980 [?]: 36) captures the historiographical continuity between Furhammar and his predecessors with regard to the reorientation of Swedish cinema in the late 1920s: “The international orientation had been cautiously commenced in the early years of the 1920s, but was pursued with full commitment, and with disastrous consequences, during the latter half of the decade.”

Scholars have since pointed out (e.g. Björkin, 1998: 284n389) that Furhammar deserves credit for actually having paid considerable attention to Isepa productions such as Hans kunglig höghet shinglar, and other films of the period that supposedly brought Swedish cinema to the brink of extinction. To some extent, this is typical of Furhammar’s general research profile, which was often oriented toward film as popular culture rather than fine art, and fueled by a fascination with the alleged low-points of Swedish film history. A case in point is the cinema of the 1930s cinema, with its many ‘pilsner film’ comedies – the most “berated cultural expression of a national format that we have ever had in this country,” legendarily lousy and notoriously vulgar, according to Furhammar (1991: 127). Either way, Furhammar’s interest in the Isepa films and the late 1920s represents a bit of a break from Werner, but perhaps not so much from Idestam-Almquist. Already in the 1940s, Idestam-Almquist (1944: 85–6) had talked about the late 1920s as a period of “decline” and “decadence,” but he put these terms in scare quotes and argued that this was an under-researched but highly interesting phase of Swedish cinema that called for special attention and closer examination.

Rediscovery and Reevaluation: Isepa, ‘New Film History,’ and the Persistence of the ‘Golden Age’ in the Historiography of Swedish Silent Cinema

Some Swedish film historians today are still not convinced that Idestam-Almquist – or anyone else, for that matter – ever heeded the call. The reason, they argue, is that earlier historians have been disproportionally invested in the idea of a ‘golden age’ of Swedish silent cinema, which not only limits the historiographical scope severely, but also tends to make films, phases, and phenomena that do not fit neatly into the success story of the ‘golden age’ into objects of derision. An article by Tommy Gustafsson (Professor of Cinema Studies at Linnaeus University in Växjö) that was published in the Wiley-Blackwell Companion to Nordic Cinema in 2016 offers a good illustration of this line of critique:

the concept of the golden age of Swedish silent filmmaking (circa 1917–1924) has governed the historiography of [early Swedish cinema] since 1936, when the first overview was published. Here a regular myth is created around 20 arty and expensive silent film classics – for example, A Man There Was (Terje Vigen, 1917) and The Phantom Carriage (Körkarlen, 1921), both directed by Victor Sjöström – and over the years these came to represent the entire Swedish silent film period both in Sweden and internationally ... Second, the existence of a golden age came to act as a watershed between periods of what, in hindsight, was perceived as substandard filmmaking in Sweden” (Gustafsson, 2016: 242–3).

With regard to the last remark – which suggests that the widespread disdain for Swedish cinema of the late 1920s is not entirely fair and balanced – we could argue that Gustafsson does not go far enough. It was not just that the period was set up to look bad in comparison to the earlier glory days, many historians (in Sweden and abroad) suggested that the international re-orientation that supposedly defined these years was the very cause of the downfall of Swedish cinema after 1924 – Florin (1997: 65–6) proposes that this is, indeed, the “majority interpretation” among historians of why the ‘golden age’ came to an end. With regard to Gustafsson’s broader historiographical point, it is easy to agree with him that cinema historians (not only historians of Swedish silent cinema) have not paid enough attention to the institutional contexts of film history, to the formation of audiences, to film culture writ large, or to any of the range of topics located beyond the canon, or beyond any specific film or group of films. With that said, Gustafsson would probably not be the first to have slightly exaggerated his predecessors’ lack of historiographical sophistication to bolster a revisionist framework. Not all early film historical work is disastrously limited in scope and depth, or bereft of empirical rigor, or clueless about the complexity of historical explanation and interpretation, even if the people who carried it out were not professional historians or adhered to the norms of historical research of present-day academia (how could they have?), and hence become easy targets in revisionist rhetoric.

Furthermore, even if we were to concede that a ‘golden age’ bias governed early historiographers such as Idestam-Almquist, Waldekranz, and Werner, we could still have reason to doubt that its persistence in a more recent, institutionalized phase of film historiography is really as strong as Gustafsson seems to suggest. Does he not all too conveniently gloss over the fact that revision, reflexivity, and rediscovery have informed scholarship on Swedish silent cinema for quite some time? With specific regard to the ‘golden age,’ we could, for example, consider Bo Florin’s 1997 doctoral dissertation “Den nationella stilen” (“The National Style”) – a standard reference and often-used course reading in the context of Swedish cinema studies. Surely, Florin’s (1997, especially chapter 1) conceptual history of the ‘golden age’ opens a historiographical vista that is potentially far more critical and nuanced than the myth-creation that Gustafsson speaks about as the dominant in the historiography of early Swedish cinema. Even if we were to argue that Florin’s dissertation’s overall investment in the notion of a ‘golden age’ somehow ends up reinforcing a too simplistic historical scheme, or too crude a periodization, it is clear that scholars were well beyond the creation of a “regular myth” by the mid-1990s.

With regard to the late 1920s, and the Isepa films specifically, rediscovery and renewed interest can be dated to at least as early as 1990, and a series of research initiatives spearheaded by Jan Olsson (at the time Associate Professor at the Drama-Theater-Film unit that was part of the Comparative Literature Department at Lund University, before being appointed Professor of Cinema Studies at Stockholm University in 1993). First, there was an ultimately unsuccessful attempt to establish a Nordic Society for Cinema Studies – the inaugural conference in Lund in 1990 featured a screening of the Isepa film Parisiskor (1928), a rarely seen film that was brought down from the Swedish Film Institute’s (SFI) archive in Stockholm with hopes of arousing the convening scholars’ curiosity about neglected areas of 1920s Swedish cinema (Jan Olsson, in conversation with the author, May 4, 2018). Toward the end of the 1990s, a more comprehensive effort along similar lines was made, now with the Giornate del cinema muto, a prominent silent film festival that takes place annually in Pordenone in Northern Italy in early October, as the key arena. Joint efforts by cinema scholars and film archivists in Stockholm and Copenhagen and representatives from the Giornate resulted in a retrospective of non-canonized Danish, Finish, Norwegian, and Swedish films of the 1910s and 1920s at the 1999 Giornate, as well as the synergetic publication of Nordic Explorations: Film Before 1930, a volume edited by John Fullerton and Jan Olsson (1999) that featured new scholarship related to the films featured in the retrospective. Olsson’s and Bo Berglund’s comprehensive preparatory viewings included Isepa releases, but none of these made it into the final festival program (Jan Olsson, in conversation with the author, May 4, 2018).

A couple of years earlier, in 1998, Mats Björkin, one of Olsson’s students, had finished his doctoral dissertation “Amerikanism, bolsjevism och korta kjolar: filmen och dess publik i Sverige under 1920-talet” (“Americanism, Bolshevism, and Short Skirts: Cinema and Its Audience in Sweden in the 1920s”), which explored the intersections of discourses of Americanization and the development of the film industry in Sweden in the 1920s. Björkin’s dissertation touched upon a wide range of issues that related to the institutionalization of film culture and film industry in Sweden. 5 It also featured analyses of rarely discussed motion pictures of the era, including Isepa films such as Hans kunglig höghet shinglar, Hans engelska fru, and Bara en danserska, as well as a handful of other mostly forgotten films of the late 1920s. The Isepa co-production venture was also addressed at some length in Patrick Vonderau’s Bilder vom Nordem (“Images from the North”, 2007: 199–208), as part of the longer history of Swedish-German film relations that the book plotted out.

It is not as if the Isepa films and their historical contexts have been subject to massive scholarly interest. However, contrary to what Gustafsson’s comment about the ‘golden age’ might suggest, neither is it the case that Swedish silent cinema has been left untouched by the ‘new film history’ – the research paradigm that emerged in the late 1970s with a promise to reconfigure academic film historical scholarship into a more methodologically rigorous and theoretically informed enterprise that would be brought to bear on a greater diversity of topics and objects of study (cf. Elsaesser, 1986; Klinger, 1997: 111; Rosen, 2001: xxi). As an exponent of the ‘new’ and the ‘now,’ it serves Gustafsson well to target supposedly conventional ideas of a ‘golden age’ to contrast his own, up-to-date approach to cinema history (which we could think of as distinctly disciplined, as in governed by current protocols of academia, yet open to the diversity of the medium’s past) with the old ways of doing things.

Framed like this – as a contested discursive construction and a historiographical trope that can also be read as an index of the development of ‘new film history’ in a Swedish context – the ‘golden age’ remains absolutely central to most scholarship relating to Swedish silent cinema, an inescapable object of deconstruction or destruction. Consider, for example, some of Gustafsson’s fellow contributors to A Companion to Nordic Cinema. Laura Horak’s (2016) mapping of the global distribution of Swedish silent film comes cloaked in revisionist ambitions to problematize the historiographical dominance of the idea of a ‘golden age,’ and to challenge the nationalist bias of much previous historiography – all to pack more punch into the essay’s main finding that Swedish films circulated much more widely and much earlier, i.e. well before the so-called ‘golden age’ than is acknowledged in “the story we thought we knew” (478; also see Horak’s introduction and conclusion in their entirety to get a sense of how revisionist rhetorics works as a framing device for the analysis). Incidentally, old-timer Idestam-Almquist [1974: 82] made the same revisionist claim in a 1974 book called Svensk film före Gösta Berling, although he did not necessarily provide the same degree of support through empirical research into distribution as Horak does.

In the case of Casper Tybjerg’s (2016) essay in the same volume, conventional notions of the ‘golden age’ are destabilized by shifting the emphasis to the transnational dimensions of Nordic film culture in the silent era, where the Swedish “art film” strategy based on literary adaptations offered a model for the other Nordic countries to replicate. Again, there is actually an echo here of Idestam-Almquist’s Svensk film före Gösta Berling, which argued [1974: 79] that the so-called ‘golden age’ was a result of transnational cooperation, not nationalist isolation. This line of revisionist inquiry was also the theme of a 2017 issue of the Danish Film Insitute’s e-journal Kosmorama titled “The Swedish Challenge,” which was guest-edited by Tybjerg and aimed to “broaden the conception of the Swedish ‘golden age’ and to illuminate its impact on the neighboring film industries of Denmark, Norway and Finland” (”Kosmorama #269: The Swedish Challenge,” 2017).

In conjunction with the publication, Tybjerg and Magnus Rosborn, archivist at the Swedish Film Institute in Stockholm, curated a program for the 2017 Giornate in Pordenone that included some of the films analyzed in the theme issue. A ”Swedish Challenge Part 2” program followed at the 2018 festival. 6 Hereby, the scholars, archivists, and random silent cinema buffs who convene in Pordenone were afforded opportunities to familiarize themselves with a number of non-canonized Swedish (and other Nordic) silent films. Many in the same crowd had already seen at least a couple of the Isepa films, at least those present for the 2013 festival, which featured screenings of Hans engelska fru and Förseglade läppar (as part of the “Sealed Lips” program) or the 2015 festival, when Flickorna Gyurkovics was screened within the “Rediscoveries and Restorations” program.

Coda: Isepa and the Swedish “Film Heritage”

The Pordenone Silent Film Festival’s interest in Isepa films and other mostly forgotten Swedish films from the silent era shows us how the scholarly effort to expand the horizon of cinema historical research and to instigate a ‘new film history’ is sometimes matched by a desire among archivists and festival programmers to look beyond the canon, not necessarily (or primarily) because they want to expand the epistemological domain, but because they believe that these neglected films has significant cultural value. For example, in his catalog notes to the “Sealed Lips” program at the 2013 Giornate, Jon Wengström (2013: 32–3), then head of the SFI film archive, wrote that a “golden age”-dominated “version of film history has led to an unfortunate neglect of Swedish films produced in the latter half of the 1920s,” and an obfuscation of the fact that Swedish cinema “still produced highly interesting films” after the end of the “golden age.”

It remains to be seen whether Wengström and others can convince the rest of Sweden of the merits of post-‘golden age’ Swedish silent cinema. If habitués of the Giornate in Pordenone have been quite likely in recent years to come across Isepa releases and other Swedish films from the late 1920s, frequent visitors to the Swedish Cinematheque (operated by the SFI) have not been as lucky, in spite of the Cinematheque’s promise to give its audience “access to all of film history” (Svenska Filminstitutet, 2015). The implication is that the rediscovery and reevaluation of this phase of Swedish film history has so far been an international affair, involving a select group of professional scholars and archivists, rather than a concern for a wider Swedish public.

Officially, the Isepa releases and other films from the same era and of the same kind all belong to the Swedish ‘film heritage’ (filmarvet), since the SFI defines the term as “all films that have received financial support from the Swedish Film Institute, or that have been screened in motion picture theaters in Sweden, or that have been submitted for review to the Swedish Censorship Board for the purpose of theatrical distribution – including Swedish as well as foreign films, feature-length and short films, fiction films, documentaries, newsreels, animations, trailers and advertising films” (Svenska Filminstitutet, 2020: 2). Arguably, this definition conveniently elides any hierarchy of value and process of inclusion and exclusion that inform the ways in which a national film heritage takes real-life shape as a cultural discourse and structured practice (cf. Frick, 2011). And it does not give a clear sense of where the SFI were supposed to begin when they were charged a few years ago with the task of digitizing the entire Swedish-produced part of the film heritage – except that they obviously had to begin by working out some kind of criteria for how to prioritize between the roughly 10,000 Swedish films that are preserved in analog form in the SFI film archive (Svenska Filminstitutet, 2018: 3; also see Svenska Filminstitutet, n.d., “About Digitization”) – just as one must assume that the Cinematheque program committee has to make certain choices when they set out to create programs that are supposed to actualize the virtual totality they refer to as “all of film history.” As the head of the SFI Film Heritage division puts it, the digitization of the film heritage is about “choosing some films at the expense of others, at least in the short term” (Svenska Filminstitutet, 2018: 3).

To be sure, a set of criteria were put in place, and it would now be possible for someone to study how these match the actual practice, as measured by the 417 films that have been digitized by the SFI since the work began in 2013 (for a list of the films that the SFI has digitized so far, see Svenska Filminstitutet, n.d., ”Digitaliserad film”). If the goal of mass digitization is maintained, and if the funding will continue to allow for the pursuit of this goal, the Isepa films and other representatives of the allegedly Not-So-Golden Age of Swedish silent cinema will eventually have their turn, and become just as “available to the public” as the rest of the digitized part of the “film heritage” (Svenska Filminstitutet, 2018: 3). Whether the Swedish public will care is another matter. Either way, these films and their reception contexts remain worthy objects of scholarly attention, for a better understanding of how Swedish cinema was constructed as a national cinema in the silent era, but also because they invite us to reconnect with the roots of the serious study of cinema in ways that render past as well as present historiographical paradigms in a clearer, more critical light.

Notes

1. All translations by the author, unless otherwise noted.

2. Complementary lines of inquiry do feature in the larger research project from which this essay originates—a monographic exploration of the influence of American cinema on Swedish film culture in the 1920s—a project that also mobilizes a much wider range of archival sources than the press material and historical work that I draw on here.

3. Examples that might be familiar to international readers include Tösen från Stormyratorpet (The Girl from the Marsh Croft, 1917), Ingmarssönerna (Dawn of Love/Sons of Ingmar, 1919) and Karin Ingmarsdotter (God’s Way/Karin: Daughter of Ingmar, 1920), all three produced by AB Svenska Bio, directed by Victor Sjöström, and based on novels by Selma Lagerlöf.

4. The passage cited here is a prelude to a later tendency among film historians to hold Paul Merzbach, the screenwriter for most of the Isepa films, personally responsible for Swedish cinema’s downturn in the late 1920s. For a striking example from a later text by the same author, see Idestam-Almquist (1944: 116–8).

5. In its highlighting of the wider institutional parameters of Swedish film culture of the 1920s, including the film industry’s conceptualization of its audience, Björkin’s dissertation offers a good example of the kind of work Gustafsson calls for in his 2016 article. But it was hardly the first work to do so. As noted earlier, wider film cultural topics were not anathema to early survey histories. With regard to later, more specialized and “properly” academic investigations, one interesting case is Elisabeth Liljedahl’s 1975 dissertation (for a PhD in aesthetics at Uppsala University). This mapping of Swedish discourses on cinema during the silent era mostly lacks the kind of revisionist rhetoric that is customary now, but nevertheless clearly explores the “institutionalization of an emerging Swedish film culture” that Gustafsson (2016: 244) is interested in. There is also a significant overlap between the objects of analysis in the chapters that Liljedahl (1975: 9) explicitly refers to as dealing with “cinema’s institutionalization” and the components of film culture that Gustafsson (2016: 243) enumerates in his article four decades later.

6. Program catalogs are available at the website of the Pordenone Silent Film Festival, http://www.cinetecadelfriuli.org/gcm/ed_precedenti/ed_prec2011-2020.html (accessed April 3, 2020).

Filmography

Isepa releases

Bara en danserska (Only a Dancing Girl, Isepa and Wengeroff-Film, 1927; dir. Olof Molander [as Olof Morel])

Flickorna Gyurkovics (A Sister of Six, Isepa and Ufa, 1926; dir. Ragnar Hyltén-Cavallius)

Förseglade läppar (Sealed Lips, Isepa, National-Film and Albatros, 1927; dir. Gustaf Molander)

Hans engelska fru (Discord, Isepa and Wengeroff-Film, 1927; dir. Gustaf Molander)

Hans kunglig höghet shinglar [“His Majesty Bobs His Hair”—author’s translation; no English release title], Isepa and National-Film, 1928; dir. Ragnar Hyltén-Cavallius)

Hon, den enda (Sparkling Youth, Isepa and Ufa, 1926; dir. Gustaf Molander)

Parisiskor (Women of Paris, Isepa and Ufa, 1928; dir. Gustaf Molander)

Other titles

Erotikon (AB Svensk Filmindustri, 1920; dir. Mauritz Stiller)

Gösta Berlings saga (The Atonement of Gösta Berling, AB Svensk Filmindustri, 1924; dir. Mauritz Stiller)

Hjärtats triumf (The Triumph of the Heart, Film AB Minerva, 1929; dir. Gustaf Molander)

Ingmarsarvet (The Ingmar Inheritance, 1925; dir. Gustaf Molander)

Ingmarssönerna (Dawn of Love/Sons of Ingmar, AB Svenska Bio, 1919; dir. Victor Sjöström)

Karin Ingmarsdotter (God’s Way/Karin: Daughter of Ingmar, AB Svenska Bio, 1920; dir. Victor Sjöström)

Karusellen (The Living Target, AB Svensk Filmindustri, 1923; dir. Dimitri Buchowetzki)

Terje Vigen (A Man There Was, AB Svenska Biografteatern, 1917; dir. Victor Sjöström)

Till Österland (To the Orient, Nord-Westi Film AB, 1926; dir. Gustaf Molander)

Tösen från Stormyratorpet (The Girl from the Marsh Croft, AB Svenska Bio, 1917; dir. Victor Sjöström)

References

Abbreviations:

AB: Aftonbladet

DN: Dagens Nyheter

FD: Folkets Dagblad

NDA: Nya Dagligt Allehanda

StD: Stockholms Dagblad

StT: Stockholms-Tidningen

SvD: Svenska Dagbladet

Bakker, Gerben (2008). Entertainment Industrialised: The Emergence of the International Film Industry, 1890–1940. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Björk, Ulf Jonas (1995). ”’The Backbone of Our Business’: American Films in Sweden, 1910–1950.” In: Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television 15, no. 2: 245–263.

Björkin, Mats (1998). “Amerikanism, bolsjevism och korta kjolar: Filmen och dess publik i Sverige under 1920-talet.” PhD Diss., Stockholm University.

de Grazia, Victoria (2005). Irresistible Empire: America’s Advance through 20th-Century Europe. Cambridge, Mass.: Harry Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Elsaesser, Thomas (2005a). European Cinema: Face to Face with Hollywood. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Elsaesser, Thomas (2005b). “ImpersoNations: National Cinema, Historical Imaginaries.” In: European Cinema: Face to Face with Hollywood. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Elsaesser, Thomas (1986). “The New Film History.” In: Sight & Sound 55, no. 4: 246–51.

E–m [pseud.] (1926). ”’Hon, den enda’ – ny kurs för svensk film.” In: NDA, Nov 9.

E–m [pseud.] (1927). ”Det första genombrottet av den nya svenska filmen efter de nya riktlinjerna.” In: NDA, Jan 18.

”Ett glatt lustspel på Röda Kvarn” (1926). In: AB, Dec 27.

Florin, Bo (1997). “Den nationella stilen:studier i den svenska filmens guldålder.” PhD Diss., Stockholm University.

Florin, Bo (2013). Transition and Transformation: Victor Sjöström in Hollywood 1923–1930. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Frick, Caroline (2011). Saving Cinema: The Politics of Preservation. New York: Oxford University Press.

Fullerton, John, and Jan Olsson, eds. (1999). Nordic Explorations: Film before 1930. London: John Libbey.

Furhammar, Leif (1980 [?]). ”Dekadens.” Unpublished manuscript, Stockholm University, Department of Theatre and Cinema Arts.

Furhammar, Leif (1982). ”Den svenska tjugotalsfilmen.” In: Åhlander, Lars (ed.): Svensk filmografi 2, 1920–1929. Stockholm: Svenska filminstitutet.

Furhammar, Leif (1991). Filmen i Sverige: en historia i tio kapitel. Höganäs: Wiken in cooperation with the Swedish Film Institute.

”’Förseglade läppar’” (1927). In: DN, Oct 4.