The home has traditionally implied a safe place often signifying stability, privacy and comfort. However it can also be used to explore fear, where danger resides in the home itself. In the film Tinker Tailor Soldier, Spy (2011) the home is more ambiguous, with the issue of visibility being key and the lack of clear division between interior and exterior combining to create a provocative screen image. The boundaries between public and private space are designed to accentuate themes around espionage.

In the following I will indicate the ways in which production designers (PDs) have helped to translate the themes from the script onto the screen. Methodologically stemming from the creative process, I begin with the professional practices of PDs in visualising a story whereas other critical literature tends to start with the finished product and use film theory subsequently to form an understanding/analysis of the work. The discussion draws on interviews I have conducted with the film’s production designer Maria Djurkovic and Set Decorator Tatiana Macdonald which illustrate their professional process.

I will be using a methodology I have personally developed called Visual Concept analysis to investigate the design of the domestic interior in the film. First established by the PD in order to tell the visual story of any particular project - the Visual Concept is defined through close scrutiny of the script and related research. Once the concept is established the PD constructs a visual contrast to ensure the concept is clear, this will then transform through the course of the film often reflecting the protagonist’s journey.

The Visual Concept methodology works through the five key ways the script is visualized by the PD:

1) Space

2) In and Out

3) Light

4) Colour

5) Set Decoration

Through the strategic use of these five tools the visual story is told. Every decision about the five elements is linked and returns to the logic of the central Visual Concept driving the design1.

Approaches to Production Design

There has been a range of work dedicated to finding an appropriate approach to the study of production design. The early writings by Edward Carrick in 1941 and Leon Barsacq in 1976 are among the first texts to compile a geneaology of cinematic design across cultural contexts and historical periods. Theorising the narrative significance of set design was undertaken by Charles and Mirella Affron in their study proposing a theoretical model that categorized sets according to levels of intensity. This is useful as a way of differentiating between the different ways a set might get used by different filmmakers or projects.

However Charles Tashiro criticizes the Affrons in his book Pretty Pictures (1998) because of their primary concern with the narrative. Tashiro says objects can have meanings of their own that have nothing to do with the script and makes a case for studying design as something that is greater than the framed narrativised image – an approach based on audience emotional engagement with spatial cues on screen.

Bergfelder, Harris and Street (2007) indicate the need to conceptualise the designer as a significant stylistic force within the collaborative context of filmmaking. Their work signals the need for further evidence to dismantle the notion of the director as singular creative author. A point echoed by Laurie Ede (2010) who stresses the necessity to avoid “hollow auteurism” as he terms it pointing out that designers are not autonomous artists but workers participating in an industrial process of production. It is this production process that the Visual Concept method relates to – the problem solving practicalities of visualizing the script for the screen while enhancing and underscoring textual and subtextual strands.

The Home on Screen

PD Richard Sylbert (1989: 22) talks about ‘getting back home’ in design, “That’s the way Mozart structured music. You always went back home… Now home and getting back home are very serious ideas in American sensibilities… there is something satisfying about getting back home. It satisfies the mind and it closes the circle.” The notion of returning home is featured in Tinker, enhancing character and story through the visual concept of the design. Home in this instance incorporates the additional nuance of country and empire to a certain extent folding in nostalgia for a lost myth of Englishness and the cultural imperialism of the English gentleman.

The house has been cultivated as a site of anxiety and disturbance in the tradition of the Victorian novel and appropriated by Hitchcock who was fascinated by the domestic space as a place of secrets and concealment (Jacobs 2013: 33). The home is a setting where a character’s psychology can be mirrored and explored. Interior landscape and layers of backstory contribute to our understanding of narrative. The character and story are particularly closely entwined in the domestic setting and this is often the place that undergoes transformation to signify the changes taking place in the narrative arc.

Tinker Tailor Soldier, Spy

Set in 1973 during the Cold War the protagonist George Smiley (Gary Oldman) comes out of retirement to try and track down a Soviet double agent within the British intelligence agency termed ‘The Circus’. The film begins with the head of the agency ‘Control’(John Hurt) meeting agent Jim Prideaux (Mark Strong) and sending him to Czechoslovakia to meet with an agent who has agreed to pass on the name of the KGB mole within the British agency. Control explains that he has narrowed down the suspects to five senior agents – Percy Alleline (Tinker), Bill Haydon (Tailor), Roy Bland (Soldier), Ricky Esterhouse (Poorman) and George Smiley (Beggarman). Prideaux is ambushed by the Czech military at the rendezvous and is

unable to complete the mission. A story featuring betrayal, nostalgia for a changing world and the loss of Empire follows the flashbacks of Smiley as he unravels the facts from the fiction.

My research findings indicate the Visual Concept in Tinker is based around the notion of visibility and invisibility, (concealing and revealing) often appearing as clues and the absence of them in the form of information. Smiley’s home is pivotal in this as it consistently conceals more than it reveals about him. Many of the other secret agents’ homes are not revealed at all and remain unknown and mysterious. The characters we do see don’t reside in happy comfortable looking homes, loneliness and isolation prevails. Jim Prideaux lives in a caravan, which extends the metaphor, he is in a little box, vulnerable in the landscape. Former intelligence analyst Connie Sachs (Kathy Burke), doesn’t have a home of her own either, instead she has a bedroom in the Oxford University hall of residence she is warden of. Agent Peter Guillam (Benedict Cumberbatch) who seems to have a home life initially (living with his boyfriend) is told to “clean it up” and subsequently splits up with his partner. Control’s flat is so unattractive and chaotic that when he opens the door to Prideaux and says “You better come in” it is not an offer we wish to accept. In contrast Smiley’s home appears calm and ordered but cold and empty.

The paradox in the design of Tinker is that its Visual Concept is also arguably one of the defining features of the work of the PD in that it is engaged in creating environments that maintain the invisible nature of their construction. In other words disguising the building of a setting to enable it to function within the codes of classical narrative cinema without drawing attention to itself and weakening the illusion. PDs state their role as in support of the story thus to a certain extent complicit in denying their own existence in order to sustain the belief in the screen fiction.

The Production Designer of the film, Maria Djurkovic finds the character and the dressing are key to the storytelling process, giving her the opportunity to establish mood and create an environment that resonates with the actors.

Every space that any character inhabits obviously has to be full of clues for that character. Control’s crazy messy flat gives us plenty of clues for his state of mind. Dressing any set is hugely important to me, I am very involved in it, it is crucial to the story telling (2015, Author interview).

Giving clues to character as Djurkovic says becomes even more relevant when spies are central to the story; what is revealed and concealed takes on greater significance.

I will now analyse the design of Tinker using the Visual Concept methodology working through each of the five categories mentioned earlier.

1) Space

The sordid world of espionage is told in flashbacks, which facilitate our movement through time and space, yet do little to elaborate on story, which remains enigmatic. The interior settings are often framed by a window or doorway creating the sense that characters are boxed in.

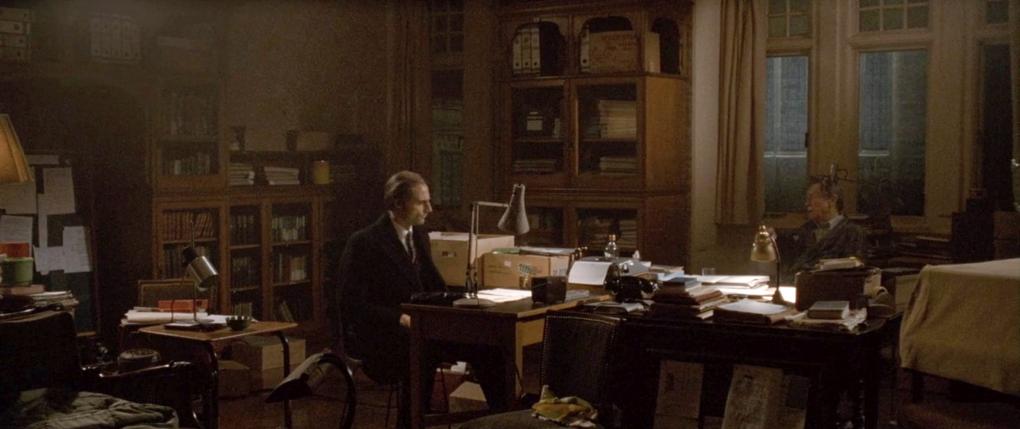

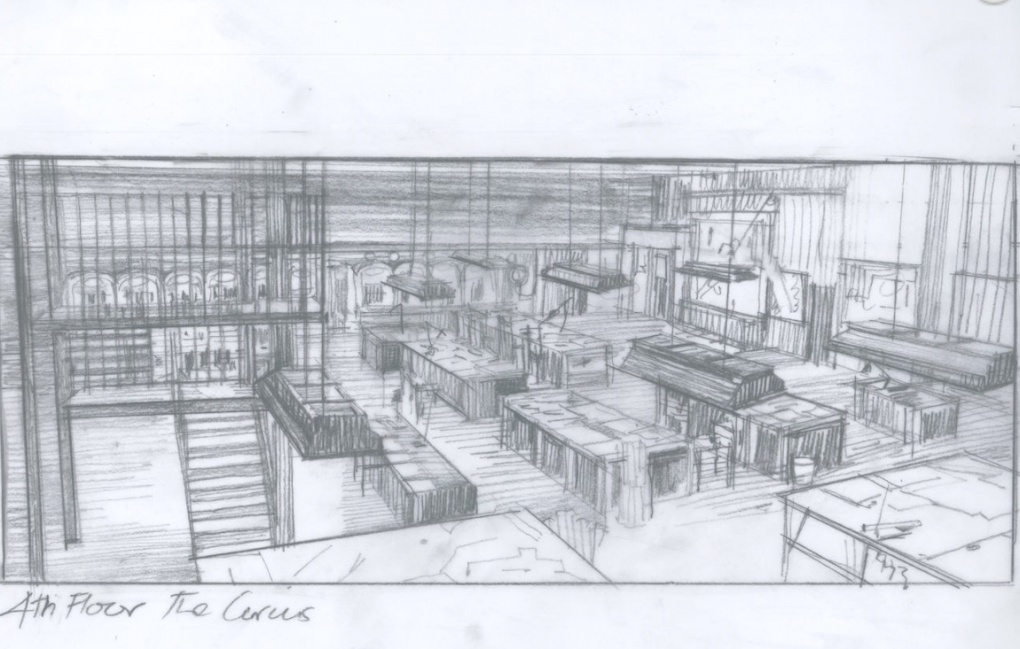

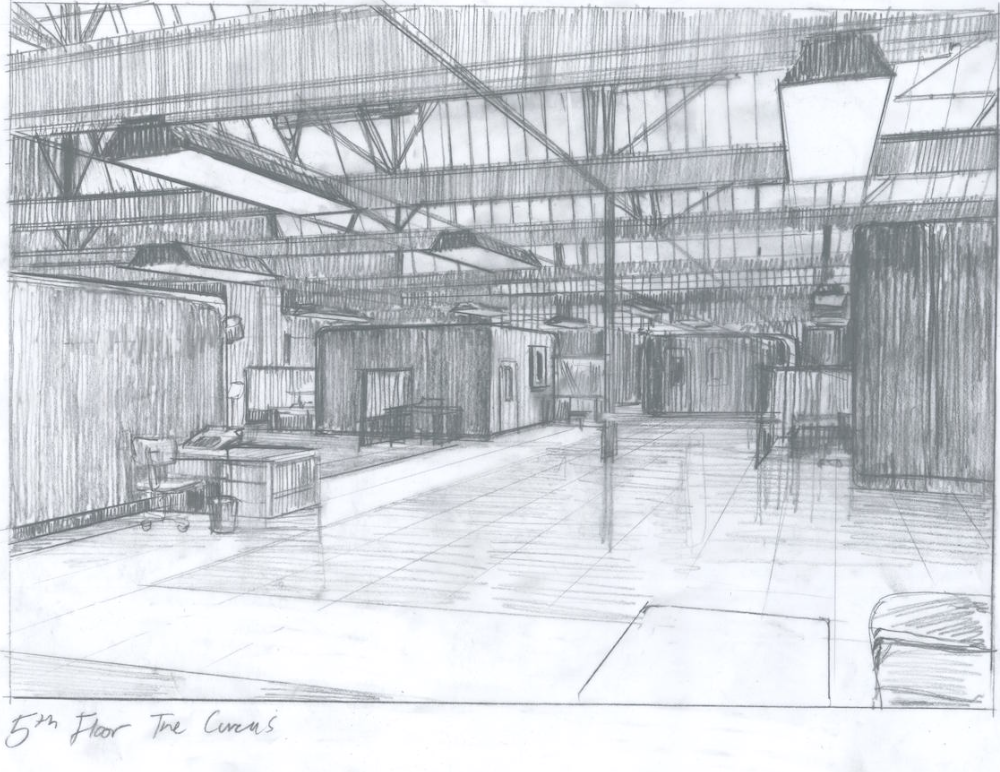

The homes create a visual contrast with the design of the secret service organization (The Circus), which appears impenetrable from the outside - a concealed anonymous exterior that reveals nothing of the nature of business within. The interiors are highly structured following lines and grids, the circulation of space is ordered without fluidity. At the heart of the organisation the meeting room is entirely enclosed – a windowless room that contains the characters in compressed space intensifying the quest for truth.

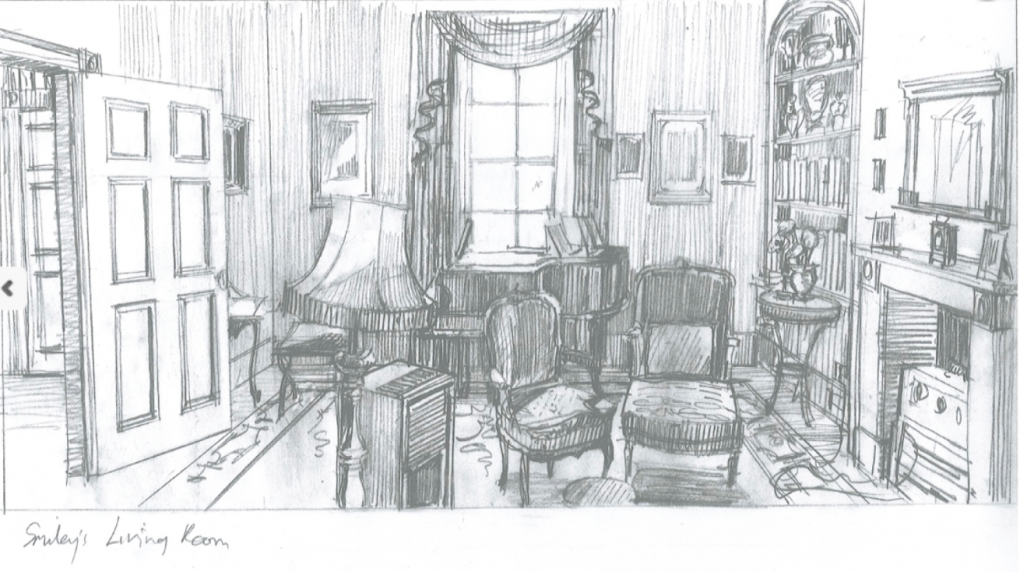

Clues to George Smiley’s character are present in his home interior if we look closely. Although initially it seems there is not that much to go on, the presence of certain details and the absence of others help us gain a sense of who he is and what motivates him. It is established that Smiley’s wife, Ann has left him and his loneliness is accentuated through the production design of his home. There is an empty quality created throughout the space evoking a feeling that something is missing. Smiley is an unlikely hero – a grey plodding, socially awkward character who collects information – piecing together through memory/flashbacks the pieces of the puzzle that eventually enable him to unravel the ‘clever knot’. He appears self contained his pursuit of information is reliant on exchange, remembrance and evaluation of vast amounts of data. The commodification of which takes the form of “treasure” or “gold” as Control terms it.

The labyrinth of the story is visualized through the navigation of the screen space, which creates pathways of circulation around the quest for knowledge and access to power through the passages, stairs, corridors, doorways and eventual arrival in the closed in soundproof boxes of The Circus or cramped domestic spaces of the agents. Character physical movement and access around and through these spaces alludes to their metaphorical insight in terms of the various plots and counter plots.

2) In and Out

Windows and doorways articulate the border between interior and exterior – linked to notions of spying. The boundaries between interiors and exteriors in the film in general are crossed, breaking down divisions between the private and the public. The audience is recurrently furnished with views looking in on characters through windows observing scenes from the outside. A theatrical sense of staging is established through these settings, framed from fixed positions characters appear boxed in and compartmentalized. The spatialisation of story enables the movement and transition of character through the complex terrain that echoes the chess board in Control’s home – each player has restrictions and limitation placed on their progression.

We see through both Smiley and Control’s windows, as such both key homes function to reveal and conceal information supporting the visual concept of the film. Once inside Control’s space everything is spilled out in front of us while Smiley’s remains serene - hiding information and his feelings under the observable surface.

Smiley’s windows are hung with nets and heavy curtains. However when agent Ricki Tarr visits him we look in on the two from the outside, unobscured by nets. The sash design contains lines within it creating further divisions, grids and compartmentalization of space and character. Ricki Tarr is situated within the left quarter frame, while Smiley is in the right. The patio doors are behind Tarr suggesting he is particularly vulnerable – observable from the front and back of the house with nowhere to hide. This is a fitting metaphor as he does reveal during this time further information that enables Smiley to edge a little closer to the truth.

Windows and glass paneling in doors create depth from foreground to background and allow us to see beyond the immediate - to look in on and observe scenes that appear private – we spy. The use of glass reflects and creates disorientating space that reinforces the Visual Concept that we can’t necessarily trust what we are seeing to be accurate. The deceptive frames within frames deliberately confuse and obscure the truth. Even the glass in Smiley’s spectacles is seen to be out of focus, which further accentuates the visual metaphor.

In another scene Smiley can be observed exiting his front door through four frames that extend the notion of a corridor as a punctuation point that includes several layers of transition and interpretation. Smiley’s front door is positioned at ground level linking interior with exterior - visible from the street creating a reliable solid sense of character. He is viewed entering and exiting, effectively connecting the interior and exterior and grounding him visually and psychologically – nothing is hidden, his portal between personal and public space is visible. In contrast Control’s flat is above ground level accessed via stairs and the door that links his interior to the hallway is dark and obscured from the exterior. His connection to the outside and possibly the real world is obstructed which suggests his access to knowledge is also concealed.

In contrast to many of the windows and doorways in the film The Circus meeting room is without windows and padded with sound insulation foam. It also features a striking mustard diagonal checked grid pattern, which intensifies the sense of enclosure and sensory deprivation.

3) Light

Smiley sits at home in the dark alone, missing his wife – reflected in the lack of illumination. In one of the flashbacks agent Bill Haydon sits at Smiley’s dining table without shoes on, we understand that he has been paying Smiley’s wife (Ann) a visit and is in fact having an affair with her. Curtains are open at the patio doors letting light in to the room. The main light source being natural light is used to suggest that some information or truth is being revealed in the scene. Back in the present Smiley sits alone at the same dining table dimly lit by artificial lamps creating a sense of isolation. Later when Smiley’s wife returns home the place is bathed in hazy natural light suggesting normality has been restored and a more positive family life is being returned to, closing the loop in terms of character journey. The domestic interior is briefly transformed into a potentially comforting and cosy space. The lonely emptiness that has predominated the Smiley home has shifted with Ann’s return and the dim artificial lighting has been replaced with natural light.

At home Control is seen sitting in front of a window that doesn’t create very much light while practical lamps dotted around sculpt the space in dramatic light and shade creating conflicting shadows and light sources without a dominant key light. The lighting in this home is more dramatic and expressive than in the Smiley home which reflects the contrast between their characters and their vision of the truth.

.The lighting in the home creates a contrast with much of the light in the work environment. As we can see from Maria’s sketches The Circus is filled with overhead lighting, these contribute to the creation of a strong grid like pattern in the workspace composed of rigid lines that box in characters and contribute to a sense of order. This is an optical illusion as the attempt to impose a system on the complex business of spying reveals the clever knot at the centre of the story does not follow a reliable pattern.

4) Colour

Although a very useful way of communicating the Visual Concept, colour can often cause contention, with many filmmakers shying away from anything too bold as illustrated by PD Stuart Craig:

The safest thing is to eliminate the colour, the more limited the palette the more effective. It allows the lighting to work. The colours that are used should be motivated by the psychology of the scene. (Author interview, 2008)

What Craig describes here is the use of a limited and often neutral palette. This is sometimes preferred by filmmakers to create a unified image connoting the internal logic and philosophy of a world, without clashing colour combinations fighting for visual attention and potentially distracting from the intentions of the work.

Maria Djurkovic considers colour one of her most useful tools in achieving the desired mood on screen.

Sketching and location scouting are the first steps in finding the visual language for the film. Colours always come from the research – I tend to play with a quite restricted colour palette and make sure that it leads us into the aesthetic world of that film.’ (Author interview, 2015)

The colours chosen for Tinker evoke the 1970s but without the usual browns and oranges often relied on for that period. The palette is not only monochrome as it may seem on first impression – it features desaturated reds, teal and mustard. The aesthetic world of the film is articulated through the palette employed. Set decorator Tatiana Macdonald says the colour springs up very quickly from Maria’s research with dirty pink used liberally to evoke the sordid underbelly of espionage.

The generally subdued colour palette ties in with the notion that something might be missing or lost. In the personal story Smiley’s wife is missing and in terms of the wider narrative perspective, the truth and morality are in question as the investigation seeks to uncover who the enemy within is. There is pattern in Smiley’s home but tonally everything ties in to the overarching neutrality of the palette. He blends into his environment in understated costume and style characterized by his ubiquitous beige raincoat. In the flashback featuring Bill Haydon the oriental rug stands out as a sickly kind of green against the dark sage walls. The colour of bile is often used to indicate moral transgression, in this scene it becomes apparent that Haydon and Ann Smiley are having an affair.

5) Set Decoration

The period setting becomes not just a Cold War drama set in the 70s but a drama set in a paisley and brown nylon idea of the 70s…The result is a film that appeals to its modern audience by being a period drama with production design as rich as any Dickens or Austen adaptation.(D’Arcy 2014)

Set in 1973 the representation of period is another strand of style that has to be part of the visual story – for example finding the balance between an easily recognizable screen version of the period and a poetic realism that captures the spirit of the times as understood from our contemporary perspective. Set in a time when smoking at home and at work was acceptable provides an opportunity to add texture to the dressing, an atmospheric haze and a tacky nicotine tinged quality pervade.

In the secret service building overlapping squares and rectangles of desks, floor tiles, light fittings, filing cabinets and so forth create grids that further embellish the labyrinth motif established through the design of space, in and out, light and colour. The Circus meeting room features a highly reflective table adding to the pattern and further disorientating spatially through texture, pattern, position and choice of materials.

The Smileys’ sitting room evokes an ordered world, with well-upholstered furniture and ornamentation. Dressing such as a piano, books, framed paintings on the wall, curtains with swagging all suggest a settled middle class comfortable existence. Moving upstairs into more intimate terrain the bedroom is comfortable and cave like with soft furnishings, more paintings and bedside tables adorned with lights. The dressing table appears to be covered in George’s estranged wife’s cosmetics, further clues to her presence in the narrative while being visually absent from the frame. As we have seen Smiley’s home reveals little of his personality and functions to maintain his anonymity. It does make apparent Ann’s preferences and the fact she is responsible for decorating choices in their home. A clear example of this is the painting George studies on the wall – a gift to Ann from Bill Haydon. Thus much of his interior landscape remains unknown in spite of his home becoming familiar to the audience Smiley remains enigmatic – the design maintains his cover and lack of exposure. The relationship and power balance with his wife is pivotal to understanding George’s character and the story. She is absent for most of the film but her presence is felt in the interior dominated by her choices.

Set decorator Tatiana Macdonald studies the script and voraciously researches other source material to gain insight about the sort of objects the characters would have around them and thinks about this and the philosophy of the story very carefully to inform decisions about the subsequent selection, combination and position of these.

I like putting in obstacles – you don’t want to treat it like a stage set and put everything around the outside, you want things that you can shoot past and through, so I tend to dress the set for visual interest and practically how that set would have been dressed according to period. I think if they have to navigate things it can make the scene so much more interesting as well, otherwise the actors are just rattling around in a box’. (author interview, 2015)

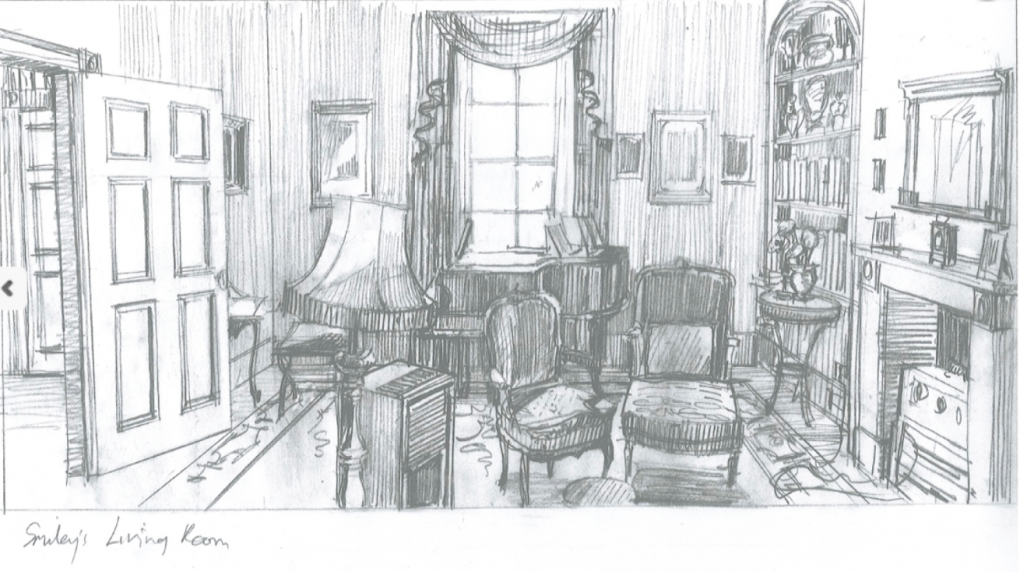

An example of this in action is the confusion and lack of organization or structure revealed in Control’s domestic space, which echoes the concept at the heart of story. Lots of fragments of information are revealed within his space that only add to the confusion and lack of clarity over who the mole in the secret service might be.

Tatiana says she prefers to source items rather than have them made because they have the patina and history of real objects that can add atmosphere to the setting. It is a small hand prop, a lighter engraved from Smiley’s wife to him that reveals information about Smiley to the Russian agent Karla. This detail exposes his wife as his weakness to the Russians who subsequently use this to their advantage. His wife’s affair is choreographed deliberately to exploit this perceived weakness in an attempt to distract Smiley from uncovering the identity of the double agent. In spite of this Smiley discovers Haydon to be the double agent and he is handed over to the authorities. Once revealed Haydon admits to Smiley,

Karla said you were good—the one we had to worry about. But you do have a blind spot. And if I was known to be Ann’s lover, you wouldn’t be able to see me straight. And he was right—up to a point.

Conclusion

Thus the production design of the domestic space is full of clues to aid our understanding of character and narrative in this complex and often obtuse film. The exterior shot of The Circus/Secret Intelligence Service presents an anonymous façade. Information is not made visible or presented in a clear transparent fashion, we have to work to put the fragments together, reflecting the process of Smiley’s journey as the protagonist. Boundaries and transition points are used to tell the visual story and contrast private and public space.

In the beginning of the film contrast is established between the two key domestic settings of Smiley and Control – a homely space and an uncanny one. As mentioned earlier Smiley’s home is defined by the absence of his wife, there is an empty quality achieved reflecting the sense that something is missing. Control’s space on the other hand is overflowing with ‘stuff’, he is consumed by his search to uncover the mole in the operation. An extreme example of someone taking their work home - Control’s space is occupied by his job, paperwork, files and books surround him in a chaotic and deranged hoarder fashion. The set decoration echoes his inner torment consumed with his job he has lost perspective and balance, confusing and disorientating – he has no idea who to trust and is lost in the labyrinth of lies.

Crammed interiors are often seen as reflection of a character stuck in the past and haunted by demons. In fact, “John Hurt said that he didn’t realise how mad Control was until he saw where he lived.” (author interview, Maria Djurkovic, 2015)

In contrast there is little evidence in Smiley’s domestic space of work or clues in terms of what his job entails. His comfortable home reveals even less about him when we understand that his absent wife has decorated and that this space is more a reflection of her character than his. This supports the central notion of Smiley as a blank canvas – who is relentless in his search for information.

The transformation of Smiley’s home is briefly glimpsed at the end of the film when Anne, his wife has returned. Never fully revealed her figure is present in the kitchen as Smiley enters the front door, the view down the entrance hall into the kitchen is lit more warmly now signifying the relief engendered by the homecoming. The circle is closed, the return home is satisfied in a narrative sense, although Smiley has not left home, his wife’s absence has rendered it unhomely. The empty shell Smiley has been inhabiting is transformed into a home on her return.

Ann’s homecoming is framed in a painterly fashion. The right half of the frame is filled with the staircase, while the left includes the hallway leading to the kitchen where a figure we understand to be Ann sits. Through the kitchen doorframe our eye is drawn to the square of light coming from the kitchen window, the scene is bathed in a hazy warm glow.

This Visual Concept approach to production design can usefully be applied to a production as an analytical tool and support a deeper appreciation of the filmmaking process. Rooted in the practice itself through considering the designer’s vocabulary for visualising a story, a deeper understanding can be achieved which can subsequently be expanded out and used in formal analysis. Through the discussion I have indicated the way in which the interior life of the character may be designed through the deliberate use of space, in and out, light, colour and set decoration to craft visual metaphor in support of the Visual Concept. Rather than describing the design as in the service of the story it is so entwined/inseparable that perhaps we should say the design is the visual story.

BY: JANE BARNWELL / SENIOR LECTURER IN MOVING IMAGE / THE UNIVERSITY OF WESTMINSTER, LONDON

Notes

1. The visual concept is covered in more depth in the book, Barnwell, J. Production Design for Screen. Visual Storytelling in Film and Television, London: Bloomsbury, 2017.

References

Alex McDowell, author interview, 2015

Maria Djurkovic, author interview, 2015

Tatiana Macdonald, author interview, 2015

Stuart Craig, author interview, 2008

Jim Bissell, author interview, 2016

Affron, C and Affron, M.J. (1995) Sets in Motion: Art Direction and Film Narrative, New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

Barnwell, Jane (2004) Production Design: Architects of The Screen, London: Wallflower Press.

Barsacq, Leon (1976) Caligari’s Cabinet and other Grand Illusions: A History of Film Design, New American Library.

Bergfelder, Tim, Harris, Sue and Street, Sarah (2007) Film Architecture and The Transnational Imagination. Set Design In 1930s European Cinema. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Carrick, Edward (1941) Designing for Moving Pictures, Studio Publications.

D’Arcy, Geraint (2014) Adaptation, Vol &. No3, Sep 2014.

Durgnat, Raymond (1983) ‘Art for Film’s Sake’. In: American Film, 8, 7.

Ede, Laurie (2010) British Film Design. A History, London: I.B. Tauris.

Harper, Sue and Porter, Vincent (2005) ‘Beyond Media History: the Challenge of Visual Style’. In: Journal of British Cinema and Television, Vol 2, Issue 1 May 2005.

Jacobs, Steven (2013) The Wrong House: The Architecture of Alfred Hitchcock. Rotterdam, NAI Publishers.

Kael, Pauline (1972) ‘Alchemy’ in Deeper into Movies, Boston: Little Brown.

McCann, Benn (2004) ‘A discreet character? Action spaces and architectural specificity in French poetic realist cinema.’ In: Screen 2004, 45

Street, Sarah (2004) ‘Production/Set Design. Introduction.’ In: Screen 2004, 45:4 Winter

Sylbert, Richard (1989) ‘Production Designer is his title. Creating realities is his job’. In: American Film 15, 3.

Tashiro, Charles (1998) Pretty Pictures and the History Film. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Suggested citation

Barnwell, Jane (2017): Spies at Home – How the design of the domestic interior in Tinker Tailor Soldier, Spy conveys character and narrative. Kosmorama #268 (www.kosmorama.org).