A street cleaner sweeps fallen leaves along a Copenhagen kerb. A grey-suited trader sprints across the stone floor of the Hamburg stock exchange. The paths of two twenty-something Oslo-dwellers cross as they walk briskly through a green summer park at the end of the working day. On the cusp of the 1960's, Danish filmmaker Jørgen Roos re-imagined the city symphony short film genre to craft portraits of three northern European cities, each film sponsored by municipal authorities. Jørgen Roos zeigt Hamburg (1962) and Oslo (1963) were commissioned in the wake of the extraordinary success of A City Called Copenhagen (1960), which had racked up a dizzying range of international prizes including an Academy Award nomination.

In the wake of the Oscar nomination, a number of cities extended invitations to the Danish documentarist, hoping to leverage the ‘Roos Touch’ (Rif 1962) to promote their cities to the world. Roos and his wife and co-producer Noémie flirted seriously with at least a Dresden film (Hartmann 1962), and invitations were reportedly received from eight cities, including Tokyo (Rif. 1962). But the two films that came to fruition immediately after A City Called Copenhagen were Jørgen Roos zeigt Hamburg and Oslo. Roos worked on these two projects more or less simultaneously during 1962, and the Hamburg film was premiered a little before the Oslo film. These three city shorts premiered in the space of as many years, between early 1960 and early 1963. Their affinities and similarities are striking; in the press, they were occasionally referred to as a city-film trilogy (‘byfilmtrilogi’, Se og Hør 1968), and critiqued for being too similar (Rif. 1962). However, it is perhaps overly simplistic to discuss the films as a trilogy as such. While they have similarities and can be brought into conversation post hoc as a kind of triptych, each film was shaped by the context of its commissioning.

It emerges clearly from the production files that the city authorities of Copenhagen, Hamburg and Oslo wanted the cachet of an art film in the tradition of the city symphony, and that the name Jørgen Roos carried with it the status of documentary auteur. The artistic ambitions of the city authorities, however, had an instrumentalist bent. In the cases of Copenhagen and Hamburg, the commissioning bodies and their stakeholders (harbour authorities, businesses, the art world) wanted a range of sites, sights, and statistics to be included in the films, but with an innovative twist. The narrative and visual cohesion which Roos and his team bring to the films, and which the funders welcome, is subject to a kind of technocratic realism which sometimes seems to lose sight of the films’ purpose: to inform foreign audiences about the cities and to attract tourists. The Oslo commission, on the other hand, was much more freewheeling, with the same emphasis on establishing a new perspective on the city. In all three cases, the use of forms of art as organising principle by Roos succeeds in reconciling the potential tension between mediation of facts and viewer engagement. On the basis of archival research in Copenhagen, Hamburg and Oslo, this article tries to trace those negotiations and examine how the city emerges from them in the three films.

As commissioned projects, as documentaries, and as creative interventions, then, the films contribute to the ongoing imagining of the cities they depict. In this sense, the three films are not alike: while Copenhagen was Roos’ hometown, his Hamburg and Oslo films were facilitated by multiple, subsidised trips to the respective cities. On the other hand, even in Copenhagen, the emphasis was on discovering the city anew, and the final version of the script was co-written with a translator and newcomer to the city, Roger Maridia. Roos uses the metaphors of sensing and moving around in the city to explain his approach to the tourist-film brief: ‘not least because tourism has stagnated, it’s important to test things out in a whole new way. You have to seek out a feeling for the city, move around the concept of what a city is’ (vest 1959) 1. This was not just a metaphor: newspapers reported that A City Called Copenhagen was partly filmed using a camera carried around the streets in a briefcase with a hole for the lens (Ekstrabladet 1960). In the manuscript drafts and in the finished films, we see the results of Roos’ and his collaborators’ encounter with the previously unfamiliar cities. And for most viewers, the films would, by design, serve as a first introduction to a foreign place, perhaps a future holiday destination. Walking in the city, then, is a condition of possibility for the films themselves, a motif and structuring principle, and an aspiration for the viewer.

Walking in the city, imaging the city

Michel de Certeau’s 1984 essay ‘Walking in the City’ is a mainstay of Cultural Studies and Urban Studies; one of those seminal yet ‘exhausted’ works of critical theory whose ‘bones have been picked over one too many times’ (Morris 2004: 676). I take the risk in this article of returning to ‘Walking in the City’ because three of its key figurations resonate so compellingly with Jørgen Roos’ city shorts. These are, firstly, the praxis of walking that is at the heart of de Certeau’s essay and crucial to the films. Secondly, both essay and films pay attention to the vertical and horizontal axes of the city, a contrast made more urgent by the growth upwards of the modern cities in question. And thirdly, de Certeau unpicks the tension between planned space and lived place, a condition of possibility for the city which Roos’ films enact not only as creative documentaries but also as planned films, products of a commission predicated on showing the people’s city as it really is.

For de Certeau, walking in the city is a fundamental act of enunciation: ‘They walk — an elementary form of this experience of the city; they are walkers, Wandersmänner, whose bodies follow the thicks and thins of an urban “text” they write without being able to read it’ (de Certeau 1984: 93). And walking has its styles, as does writing: ‘The walking of passers-by offers a series of turns (tours) and detours that can be compared to "turns of phrase" or "stylistic figures." There is a rhetoric of walking’ (100). In French, the pun, and thus the metaphor, can be extended to encompass film, given that the verb tourner also collocates with film, simply meaning ‘to make a film’. In Roos’ city shorts, scenes of walking are not just a matter of documenting life on the city streets: walking is essential to the plot in Oslo, and fundamental to visual choreography and to characterisation in all three films. While de Certeau has been criticised for offering a ‘universalizing meta-model’ of walking and thus eliding the multiplicity of experience that his essay seeks to render visible (Morris 2004: 677), film, by its nature, shows us the walkers in all their individualised experience.

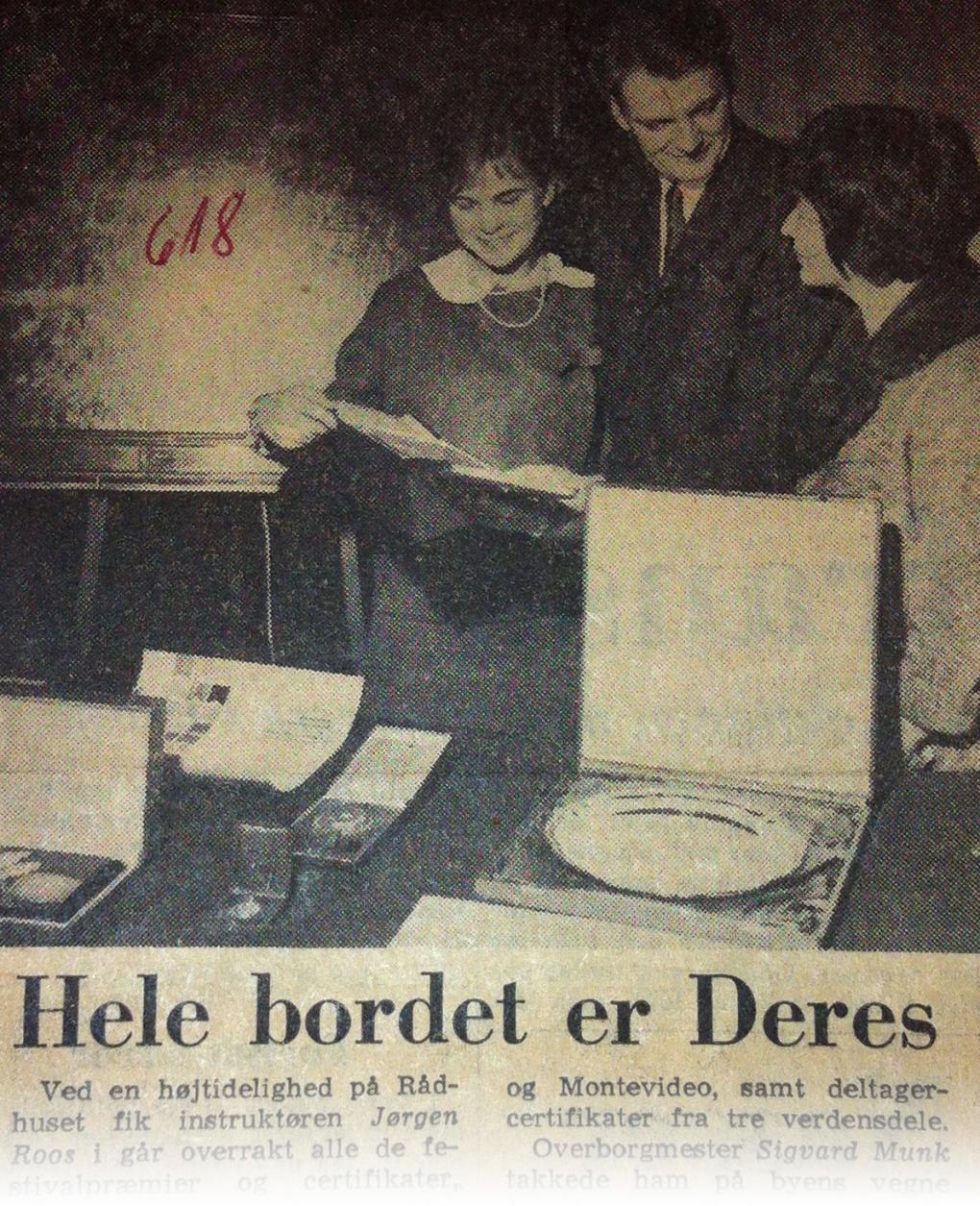

The starting point for de Certeau’s essay is a meditation on the 110th floor of the World Trade Centre in New York City, a vantage point rendered all the more poignant after 2001. While the WTC still stood, as de Certeau observes, it provided a planner’s eye view of the city below, while the walkers themselves were so small as to be invisible. He draws a parallel between the centuries-old drive to render the city legible, to perspectivise it, and the pleasure he experiences as a voyeur on high: ‘the fiction of knowledge is related to this lust to be a viewpoint and nothing more’ (92). While there were no buildings in Copenhagen, Oslo or Hamburg in 1960 that could offer the dizzying perspective of the World Trade Centre, Roos is nonetheless repeatedly drawn to film from a height. In Copenhagen, this entails confronting the viewer with a completely new aerial perspective on the City Hall, impossible a few months before, from the newly-completed SAS hotel. In Oslo, we find ourselves in the cabin of a crane, looking out onto that city’s town hall. And in Hamburg, the tracts of water separating city from working harbour have a comparable perspectival effect.

Clearly, in pointing out these affinities, I do not mean to suggest that Jørgen Roos as director was influenced by a work of critical theory that appeared twenty years after the films were made. In terms of temporal coincidence, a better bet would be Kevin Lynch’s book The Image of the City, which was published in 1960 in the USA, and argues that city planners must pay attention to people’s need to orient themselves visually and with the other senses. Lynch identified a typology of paths, edges, districts, nodes and landmarks which help city dwellers to ‘read’ their city, inhabit it emotionally, and develop mental maps based on memory and experience. Indeed, in Roos’ films we catch a glimpse of the demolition of old neighbourhoods as part of an ambitious programme of city planning for the new decade, and the landmarks Lynch saw as so necessary play a central role in the films: Copenhagen’s SAS hotel, or Oslo City Hall. Roos’ films pose the question — quite literally and repeatedly in the case of A City Called Copenhagen — ‘what is a city?’. However, they do not answer the question, or at least not in prescriptive or programmatic terms. Nonetheless, both in the finished films and in the commissioning briefs, we can discern the kind of shift that Anthony Raynsford sees as fundamental to the planning culture from which Lynch’s book emerged around 1960:

It was a shift within urban design from an ‘organic’ conception of the city to a ‘psychological’ conception of the city, from the ideal of a culturally and functionally integrated city to that of a city characterized by individually and culturally distinct perceivers. It was a shift from a focus on the social and historical meaning of the city to a focus on the personal and subjective meaning of the city. (Raynsford 2011: 45)

This chimes, too, with the more philosophical version of the question as posed by Eiler Jørgensen in his script for Roos’ Oslo film: is the city a place where the real is unreal and the unreal is real? Whatever the answer, the city is still a place where filmmakers and city walkers alike ‘sense scents and feel asphalt and cobbles through the soles of their shoes’ (Jørgensen and Roos 1962: 1).

It feels counterintuitive to suggest that films commissioned by the city authorities can engage with these ‘personal and subjective’ mappings of city dwellers. Nonetheless, neither do Roos’ films content themselves with rendering landmarks and nodes visible. I want to suggest that the films’ common interest in walking enables them to gesture to the paths that individual feet take through the city, and the mental maps that coalesce as a result. As both Lynch and de Certeau suggest, the city grows out of the organic mis-uses and misunderstandings of the work of planners.

Twenty years later, de Certeau’s essay crystallised or codified a sense of resistance to that planning culture, emphasising the artificiality of the city model and its detachment from the lives of the city dwellers:

Is the immense texturology spread out before one's eyes anything more than a representation, an optical artifact? It is the analogue of the facsimile produced, through a projection that is a way of keeping aloof, by the space planner urbanist, city planner or cartographer. The panorama-city is a ‘theoretical’ (that is, visual) simulacrum, in short a picture, whose condition of possibility is an oblivion and a misunderstanding of practices. (de Certeau 1984: 92-93)

De Certeau has been critiqued for making too much of the ‘misunderstanding of practices’ — the planner’s ignorance of how people use the city, and the citizens’ misuse of its paths and spaces. Explicitly influenced by Foucault, de Certeau at times alludes to the city authorities in hyperbolic terms:

the city, for its part, is transformed for many people into a ‘desert’ in which the meaningless, indeed the terrifying, no longer takes the form of shadows but becomes, as in Genet's plays, an implacable light that produces this urban text without obscurities, which is created by a technocratic power everywhere and which puts the city-dweller under control (under the control of what? No one knows) (103)

As Morris argues, de Certeau posits too rigid an opposition between the official and the everyday:

Social practices of walking rarely conform to this either/or model. It is never simply a case of ‘us’ and ‘them’, or individual walkers versus the city authorities who seek to organize the movement and dispositions of bodies in urban space, as Certeau’s model implies (Morris 2004: 679)

This tension between power and resistance is thought-provoking in the context of the commissioned city film, insofar as the filmmaker’s assigned task is to capture the city of people — but under the watchful gaze of the city authorities’ film committees. As suggested above, this article tries to show that the films and the cities they depict emerge from a set of relations which are more tentative and nonlinear than a city authority imposing its vision on the film.

The city symphony

The strictures of film genre can also act as a kind of straightjacket as well as a creative fillip, consolidating relations of power and resistance. Roos’ three films can be seen as late-blooming city symphonies, but self-consciously so; self-consciously on the part of the commissioning bodies as well as the film texts.

The foundational texts of the city symphony genre date from the 1920s and include Alberto Cavalcanti’s Rien que les heures (Nothing but Time, 1926, France), Walther Ruttmann’s Berlin, Symphonie einer Grosstadt (Berlin, Symphony of a Great City, 1927, Germany), Dziga Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera (1929, USSR), Joris Ivens’ Regen (Rain, 1929, The Netherlands). As the nomenclature suggests, typically, the films are structured into symphonic movements, tracking the life of the city over a single day, or rather, a ‘composite day’ (MacDonald 1997: 3). There is a tendency to offer a taxonomy of occupations, classes, neighbourhoods, and so on, constructing an Olympian perspective on an unfathomably large and complex social organism. A calling-card of the genre is self-conscious use of montage, which enacts the cities as machines of rhythm and pattern. Erica Stein explains that it was precisely these aesthetic strategies that soon made Ruttmann’s Berlin in particular a target for politically inflected critique: ‘The legibility lent to the usually overwhelming onslaught of technology, industry, and spectacle that compose the quotidian reality of the modern urban dweller produces a corresponding erasure of the socioeconomic order’s alienating, exploitative qualities and its historical context’ (Stein 2013: 3–4). For similar reasons, John Grierson (1966: 151-2) saw the city symphony as ‘the most dangerous of all film models’.

In circumstantial terms, there is a direct line of descent between Roos’ 1960's trilogy and some of the classics of the genre. During the planning stages of A City Called Copenhagen, Dansk Kulturfilm, the agency managing the commission, organised a screening of a selection of city symphonies for Roos and representatives of the commissioning bodies. The three films screened were Ruttmann’s Berlin as well as two films of 1948: Arne Suckdorff’s Oscar-winning portrait of Stockholm, Människor i Stad (Rhythm of a City), and a less-well known film set in Edinburgh, John Eldridge’s Waverley Steps (Thomson 2018: 179-81). Feedback on Roos’ first draft from Sigvald Kristensen of the Danish Foreign Office also indicates a good knowledge of earlier city symphonies as intertexts, in that the advice was to steer clear of previously-used structuring principles and find a new concept to underpin the film (Kristensen 1959).

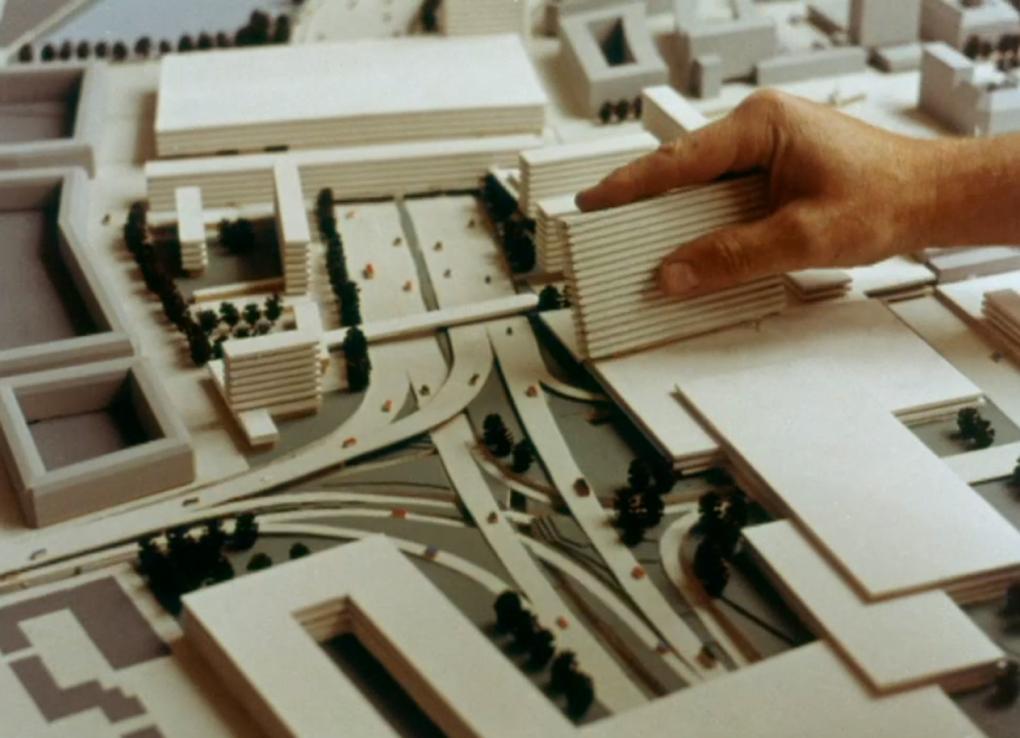

Roos’ three films adhere to the city symphony tradition in terms of temporal structure. A City Called Copenhagen incorporates found footage from the 1910s to bring the streets and squares of the past into conversation with the present and future. The throng gathering outside the palace on the king’s birthday at the end of the 1950s and fifty years before are juxtaposed; a turn-of-the-century street prophet called Curly Charlie warns ‘beware of the future! In fifty years, the city as we know it will be gone’. With a cut to present-day city planners smoking over their scale model and the SAS Hotel as the concrete-and-glass result, the voiceover declares: ‘The future’s already here’. As I have discussed at more length elsewhere (Thomson 2018: 170-193), the SAS Hotel in particular not only plays a symbolic role in the film as the concrete expression of the modern city, but actually enables new perspectives on Copenhagen. The block provides a vertical perspective as it looms over Vesterbrogade, and, as Scandinavia’s first high-rise, a skyscraper’s-eye-view of the town hall square and the city beyond via use of the temporary elevator on the side of the unfinished building. The film also self-consciously writes itself into the city symphony tradition by starting with the fireworks over the Tivoli Gardens, a visual nod to the end of Ruttmann’s Berlin. The fireworks constitute a false ending at the very beginning of the film, announcing the ironical and light-hearted tone that characterises the film’s mediation of city statistics and serious questions about urban life. But otherwise, A City Called Copenhagen is not structured around the rhythms of a day: it deals with much longer cycles of time, especially the half-century between Curly Charlie’s warning and the cusp of the 1960's.

Jørgen Roos zeigt Hamburg, on the other hand, opens with a kind of wink to the city symphony: a light goes on in a window of a silhouetted house in the pre-dawn light, and this is followed by a montage of the city — including animals at the zoo — awakening from slumber. A similar sequence ends the film, with the light in the same window going out. In between, the viewer has witnessed a daily cycle of work and leisure, with particular emphasis on the wide range of nightlife offered by the city, from ballet to exotic dancing. In juxtaposing a gnarled old eel vendor with the snappily-dressed gents scurrying through the stock exchange, the film flirts with the kind of mechanistic social equivalences which Grierson and others thought so dangerous in the city symphony. There is a double bind in play here: in showing the full range of city lives, the poor, the elite and everyone in between, juxtapositions are inevitable, and all are drawn into the temporal rhythms of the city.

Oslo is structured around yet another temporal cycle: the seasons. From the very beginning of the film, the contrast between winter and summer in the city is emphasised. A worker is sprinkling salt on the tram tracks as a tram gingerly makes its way down a curved slope. The image then cuts to the same setting in summer. This juxtaposition is used several times in the course of the film, with Vigeland sculpture park, individual sculptures and city streets being shown in summer and winter garb. The seasonal conceit is shot through with the daily cycle of work and leisure, but this is less consistently applied than in the Hamburg film. A third kind of time explored in Oslo is more experimental: paths that cross in time and space. The film follows a young man and woman through the daily grind: they almost meet in a cafe, and almost meet again as their trajectories cross in the park on the way home. A montage of the young lovers echoing the compositions of various sculptures and paintings on the Oslo fjord renders visible what could have been if they had met. The contingency of time is repeatedly emphasised in the film by freeze frames of the couple in mid-stride, people on park benches, bustling city streets. Pointed shifts between still and moving images works with the emphasis on seasonal changes to render the passing of time tangible and poignant.

The three films thus gesture knowingly to the city symphony genre, but also play with it in a variety of ways — never quite escaping the risk of totalising and romanticising the city as machine with all the social and symphonic moving parts in their rightful place. In a very literal sense, however, all three films are symphonies: they all rely heavily on music to communicate the complexity and contrasts of the city. Despite its reliance on a voiceover bubbling over with personality, A City Called Copenhagen includes a broad range of music from, especially, popular sources: the jazz clubs springing up around the city and attracting international musicians, the folky songs in beerhalls, the sounds of the Tivoli Gardens and Bakken amusement park, live swing music at the municipal outdoor dances. All of these are reprised in a sound montage as the camera is lifted upwards in the hotel elevator and the end credits roll. The Hamburg film, too, relies heavily on the wide variety of music that characterises the city: sea shanties, orchestral compositions, folk songs, cabaret — though Roos did not capture The Beatles, who were resident on the Reeperbahn at the time the film was being shot. As the city’s film committee decided to eschew voiceover, so that the film could more readily be exported (Filmkreis 1962a), music and the ambient sounds of the city must do the heavy lifting of communication. While Oslo originally had a voiceover composed as a prose poem by Eiler Jørgensen and spoken by Claes Gill, a second version of the film made in 1968 relies only on music composed by Per Nørgård. The use of one over-arching, specially composed piece is conceptually different from the ‘sampling’ of popular and classical forms employed by the other two films.

If we now turn to look at the commissioning and production of each of the three films in more detail, we will see how the city symphony genre in particular and the more general idea of film as auteur-led art permeates the respective briefs. In each of the three cases, the commissioning authorities explicitly wish to eschew the traditional tourist film, though the films were meant to attract domestic and foreign visitors. The impetus to craft films which emphasise the everyday, lived experience of the city is more or less explicit in each of the briefs. In this sense, the ‘technocratic power’ which de Certeau pits against the urban meanderers in his vision of the city is actually interested in using the un-planned aspects of city life as the underpinning theme in the city films commissioned. Roos responded with films that make the people — understood as individual citizen and collective citizenry — visible. In particular, this entails engaging with how they move through the city, a theme that unfolds differently in the three films, but which allows for an exploration of planned and lived space.

COPENHAGEN 2

The last 45 seconds of A City Called Copenhagen consist of a single shot filmed from what is clearly the temporary elevator on the side of the unfinished SAS hotel. As the camera moves upwards, the view to the east, towards the town hall and its square, is seen through a layer of chickenwire on the elevator cage, echoing the industrial structures of the harbour on which the middle section of the film lingers. Here at the end, though, as the credits come and go, and segments of the film’s many musical genres are re-played, the upward journey of the camera focuses the gaze on the shifting perspective on the town hall square beyond. First the dome of the Axelborg building, then the cars on Vesterbrogade, disappear beyond the bottom edge of the frame. By the time the cage jerks to a stop and the screen fades to black, what is centre stage, haphazardly framed by the bars of the lift shaft, are the tiny human figures strolling across the town hall square, just at the limits of visibility. From a height of just under 70 meters, the perspective is not as distanced as that of de Certeau atop the World Trade Center. But this is a film that has asked us to pay special attention to its closing sequence, by opening with a playful ‘false ending’. If we do, we find ourselves high up on a building which the film has associated with the planners of the future, its metal scaffolding self-consciously framing the organic criss-crossings of city life down below.

The closing sequence of A City Called Copenhagen elevates the viewer above Rådhuspladsen, offering a view that would have been unthinkable before the construction of the hotel. The music here is a compendium of the film’s diverse soundtrack.

After the faux-touristy opening slideshow, the first figure we meet in A City Called Copenhagen is a portly and green-jacketed fisherman sitting on the harbour wall. There are not many fish in the harbour, explains the voiceover, but you are entitled to investigate for yourself because Copenhagen (here the voice assumes an exaggeratedly grand tone) is the capital of a democracy! That this fisherman appears again at the end, and is told by the voiceover he can pack up and go home now, underpins his role in establishing a key theme in the film: the space of the city is planned and developed in a variety of ways by the municipal authorities, but Copenhageners nonetheless use the space in ways that are often improvised and chaotic. Asked if he can answer the question ‘what is a city?’, the fisherman just shrugs and trundles off home — but in his framing role as a cipher for democratic use of city space, he has obliquely answered it.

Our encounter with the fisherman segues into an introduction to the City Council of Copenhagen, the grandeur of the city hall punctured by a somewhat insolent on-screen caption and accompanying trumpet fanfare over-emphasising the film sponsor’s largesse: ‘This film is sponsored by the CITY COUNCIL of Copenhagen’. One of the film’s first tasks is to provide an overview of the public services for which the City Council is responsible. Two sequences transform what could have been a boring litany of amenities into an engaging tour through the city’s everyday spaces. The budget of 1.5 billion kroner a year, the voiceover says, pays for a myriad of public services: schools, dentistry, swimming pools, modern education, new school buildings, hospitals, fire stations, power stations, public parks, libraries, markets and street cars. The voiceover speeds up as the list progresses, as does the aural punctuation: after each item, a ‘ching!’ sound evokes a cash register at first, then the bell of a street car. As we career towards a stop sign, the narrator rounds off the list of amenities by saying ‘and that’s not all! But it’s enough. Anyway, it’s boring.’ A dog appears on screen, yawning noisily, and thus pre-empting any possible boredom on the part of the viewer. A second list applies the term ‘municipal’ to a range of activities that visually connect the private with the public. As small children toddle across the screen and dancers’ multicoloured skirts swish, the narrator comments that there is not only ’municipal low-rental housing’ but also ‘municipal chamber pots in all the municipal kindergartens’, and that ‘there are even municipal dances in the parks’. As each item on these lists is narrated, footage of cute or characterful children and adults translate the abstractly planned or municipal into the concretely lived.

These sequences can be seen as a creative response to the constraints of the original brief. International demand for a short film about Copenhagen had been identified in the early 1950s by the Foreign Office’s Press Bureau, which was responsible for disseminating knowledge about Denmark abroad. Foreign Ministry official Sigvald Kristensen wrote to Mayor Hans Peter Sørensen in 1954, explaining that there was a gap in the market for a film about Copenhagen that would ‘give foreign audiences an in-depth insight into life and work in a modern, democratic capital city’ (Kristensen 1954). What he wanted was a new film that showed life in the capital from the average citizen’s point of view:

The film ... ought to be concerned with his living conditions, his responsibilities and rights as a citizen, his efforts in the workplace and as a member of the community and the results of these efforts: a democratically-run, modern city, where the constant goal is to create better conditions for the individual citizen. (Kristensen 1954)

It is striking that in the same letter, not only does Kristensen provide guidelines for the film’s point of view and focus, but also characterises the anticipated audience in unusually precise terms:

The film should, first and foremost, target an engaged audience in schools, continuing education and interest groups around the world, whose interest in and respect for the Danish way of life we would like to win. The Press Bureau is convinced that such a film will also be able to serve the interests of the tourist industry more effectively than a tourist film of a more conventional type. (Kristensen 1954)

Wrangling about funding and the remit of the film continued through the second half of the 1950s. Funding constraints meant that the filmmaker would be restricted to shooting in black and white and on 16 mm, which led to the first choice of director, the Oscar-winning Swede Arne Sucksdorff, turning down the commission. Jørgen Roos was then approached and was also disappointed by the proposed format, but accepted (extra money for shooting on Eastmancolor was later found; see Thomson 2018: 189-90). A particular point of contention was the Port Authority’s contribution to, and presence in, the film (see Thomson 2018: 178-9), but overall, a similar set of principles made it through to Roos’ first draft in 1959:

What was wanted was not a film based on the traditional notion of the city as a tourist destination. On the contrary, the film should try to capture the city’s special atmosphere, say something about the people who live here every day, their work and their pleasures. At the same time, social conditions should be covered, and the harbour should be brought into the picture. (Roos 1959: 1)

Roos brings the harbour into the picture in two ways. Firstly, by repeating the visual joke of splashing the sponsor’s generosity across the screen over a panorama of the docks: ‘This film is also sponsored by THE HARBOUR ADMINISTRATION of Copenhagen’. And secondly, by interweaving the obligatory statistics about the harbour with a film-within-a-film, one which follows the painter Preben Hornung around the docks as he seeks inspiration for his abstract art. Hornung’s cycle ride and stroll carrying his canvas and finally settling down to paint allow for a tour of the harbour’s functions, but also a closer look at the textures, colours and fabrics of this hidden side of the city.

The emphasis in A City Called Copenhagen on popular and fine arts as a means to explore the question ‘what is a city?’ also grew out of the symbiosis between commissioning body and filmmaker’s vision. Roos’ first draft shaped the proposed film around interviews with half a dozen leading Danish cultural figures, including the cultural critic and lamp designer Poul Henningsen (see Thomson 2018: 184-5). It proved to be too difficult to control the result; a second draft begins to resemble a city symphony more closely. Sigvald Kristensen at the Foreign Ministry was sent this draft, and provided feedback on it. His report (Kristensen 1959) encourages the development of the aspects of the film that deviate from, or renew, the city symphony. He urges inclusion of a wider range of ‘distinctive, curious, relatively unknown’ aspects of city life. He wants to see a more distinctive ‘leitmotiv’ or conceptual source of coherence, citing Ruttmann’s use of time as a connecting conceit and Sucksdorff’s focus on love in the ‘stony city’. For Roos’ film, he suggests the pairings new-old, peace-noise, oasis-technology and life-art as possible frameworks. The tension between life and art, thinks Kristensen, is already there implicitly in the draft and is ‘very original’.

The life/art theme shapes the finished film not just in the figure of Hornung, but also in the emphasis on popular forms of art. These include circus-style shows and funfair attractions for children and adults alike at the amusement parks Tivoli and Bakken, and folksy song and cutting-edge jazz in variety halls and cellar bars. A sailor being tattooed in a Nyhavn shop is the foil for the narrator’s verdict on popular art: ‘no operation can remove it, and please don’t try’. A side-effect of the emphasis on popular amusements and arts is that Copenhagen emerges not so much as a city of walkers, but as a city of crowds: thousands shouting frustratedly at a soccer game, rows of screaming children at Tivoli, a jazz bar full of drumming fingers and nodding heads, or waving subjects in front of the royal palace both in 1959 and 1909 for the respective kings’ birthdays. And yet here, too, the film pivots back to the individual at street level: as a broom is pushed along the gutter, the voiceover muses that ‘maybe the city is a street cleaner?’, introducing a municipal worker who would be among the crowds on the king’s birthday, and thus connecting state and citizen, planned city and lived city.

The tension between its status as commissioned film and its humour and charm is an aspect of A City Called Copenhagen that is emphasised by several reviewers after the 1960 premiere. For reviewer V-r in Aktuelt, for example, it is this very culture clash that will, he surmises, make the film effective as an advertisement for the city out in the world:

Insofar as it is carefully emphasised that the Danish Government, the Danish Government Film Committee, Copenhagen City Council, Copenhagen Harbour Administration and, as producer, Statens Filmcentral are behind the project, the foreign audience which the film targets will truly get the impression that humour is something we are very good at in the little land of Denmark. The film demonstrates in its own right that humour is related to wisdom; there is something fresh here that will make itself felt in the film’s worldwide charm offensive. (V-r 1960)

Indeed, A City Called Copenhagen became a worldwide sensation. There was nothing unusual about kulturfilm for foreign consumption being versionised in UK and American English, French, German, Spanish and other major languages, but it was less common for a film to attract requests for Finnish, Japanese and even Esperanto versions. A special prize-giving ceremony at Copenhagen Town Hall had to be organised in October 1961, to highlight the film’s awards from festivals including Cannes, Edinburgh, Oberhausen, Buenos Aires, Mar del Plata, Bilbao, Rapallo and Montevideo (see Thomson 2018: 191-92 for an account of the film’s international distribution).

HAMBURG

Despite, or perhaps because of, the irreverent treatment of city authorities in his Copenhagen film, Hamburg City Council asked Jørgen Roos to make a film about the city in spring 1961. The project was overseen by a Film Committee (Filmkreis) whose secretary wrote to Roos with a rough remit and the invitation. It is striking that the commissioners are aware of the difference between filming a city one knows well, and one that is unfamiliar:

The film should promote the city as a tourist destination. Accordingly, it should encourage as many visitors as possible from within Germany and abroad. To say much more than that would have little purpose. Come to Hamburg, take a look at the city and its people. It will be entirely up to you to decide how to work out a kind of program together with all the agencies and people who can tell you something about what you want to see in Hamburg. We will not send you any books or lengthy information about Hamburg, because you no doubt want to develop a sense of the atmosphere of our city for yourself. (Filmkreis 1961a)

Immediately here we see that the film was conceived as one that would, like its predecessor, avoid the clichéd tourist image of the city, in part by not allowing published guides to pre-empt the filmmaker’s individual encounter with Hamburg. Two visits to the city in November and December that year were organised for Roos and his co-producer wife Noémie Roos. During the first visit, they had the chance to view the city from the air in a chartered plane. The programme for the second visit is indicative of the range of sights, sites and activities to which Jørgen Roos was exposed while planning the film. The schedule includes a play at the Schauspielhaus theatre; visits to the Stock Exchange and to the Verein Hamburger Seehafenbetriebe (associated sea port companies of Hamburg); a concert at the Übersee-Club (a cultural and commerce club); a fish auction; a reception at Hamburg Senate (municipal authority); and private dinners with members of the Filmkreis (Filmkreis 1961b). Most of these places appear in the finished film.

In his first draft of the film, with working title IN HAMBURG IST WAS LOS (Something’s Going on in Hamburg), dated April 1962, Roos emphasises the democratic, workaday selections of foci as instructed in the brief. I quote this document at some length to show how much emphasis was given to the notion of ‘Hamburg in shirt sleeves’:

In the following manuscript, I have tried to change the general tourist aspects in order to take advantage of the special possibilities that the film offers us, namely to show the things and events that the tourist almost never sees and experiences. This allows us to capture the city's own personal atmosphere - Hamburg in shirt sleeves. You have to constantly strive to make the viewer feel that we are looking through a keyhole at a working day … The city is not served up on a presentation platter, but in the course of the film we circle theme and city and thereby achieve something special and distinctive — something mysterious. The tourist ‘viewpoints’ and ‘sights’ are omitted, except where they enter as a natural part of the working day of the people we describe.

There must be glorious faces in the film, different types, people who are really busy in their work. It is the people who shape a city, each one in its own way, that brings about the functioning of the complex mechanism that represents the life and spirit of the city. (Roos 1962a)

Another interesting feature of the draft is that it articulates a distinctive approach to the temporality of the city. The films should capture the energy of events before they have happened, writes Roos:

Telling events BEFORE THEY HAVE ACTUALLY HAPPENED! Nothing is finished, everything is in preparation, the city is preparing. It creates a tension by describing the prelude to the actual; one builds up a strong energetic development…(Roos 1962a)

This principle is indeed carried out throughout Jørgen Roos zeigt Hamburg. When layered on to the film’s adoption of the classic city symphony structure of dawn to dark, this strategy creates a subtly distinctive approach to the cycle of the working day. The film is structured around three ‘shifts’, to which it devotes equal time (each sequence lasts almost precisely three minutes). Firstly, office and industrial workers are seen moving towards their working day; secondly, the choreography of street life unfurls during the daytime; and thirdly, the artists and performers of the nighttime economy start to prepare for their turn. The logic is indeed that every movement anticipates another event; everyone in the city is — literally and figuratively — moving towards something which has not yet happened. The incessant focus in the film on how bodies move through the city supports the temporal trope of anticipation of events, while also facilitating comparison across social categories making up the ‘complex mechanism’ of the city, such as class, profession, age, gender and physical ability. Each city dweller walks in their own shoes.

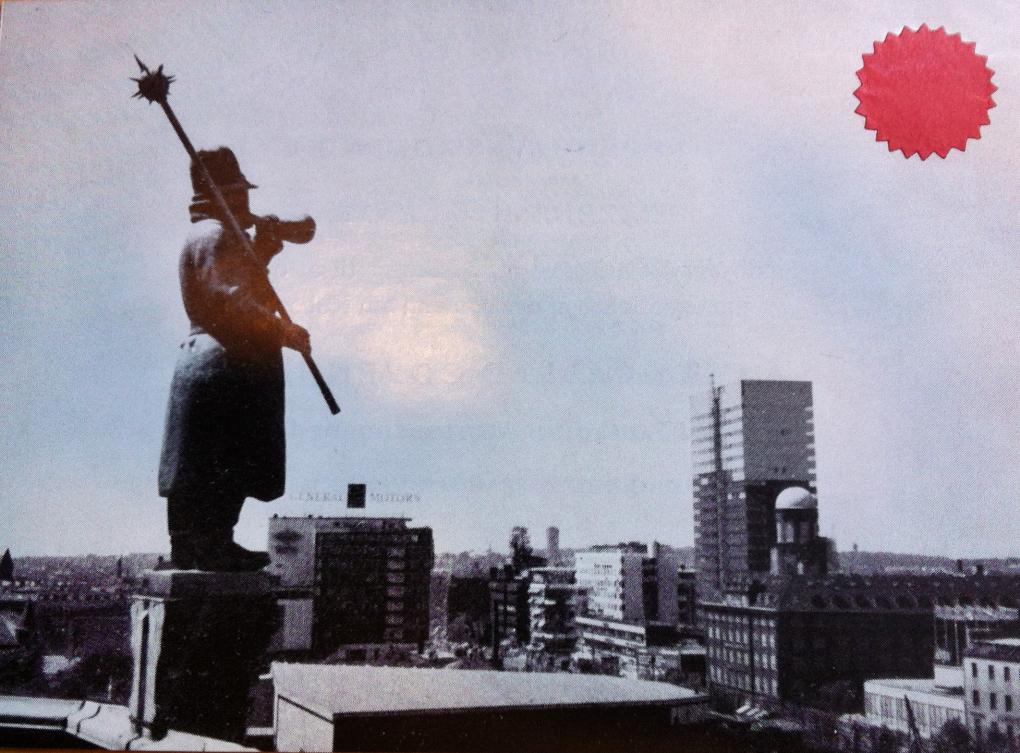

The film begins with a wink from the light in the house by the harbour. An anthem accompanies the hoisting of a ship flag; workers are seen sleeping in their delivery vehicles before their shift; women, cleaning staff perhaps, bustle into a high rise office building; wharf crowd onto boats to be ferried across the harbour to work; and shopkeepers set out their street displays. A waiter tossing newspapers onto cafe tables is juxtaposed with a liveried clerk setting out papers for a Senate meeting. Everywhere, people are walking, often filmed from pavement level to emphasise the patterns and variations of shoes and strides. Harbour workers lope across the pontoon and sway on the ferry; a briskly moving crowd of commuters is reflected in a sunlit plate glass window; the confident stride of a single businessman rounding a corner to an antique shop is punctuated by the swing of the newspaper he is holding. The camera picks out memorable faces: a middle-aged dockyard worker coughing over his morning cigarette, or a glamorous driver in heels click-clacking away from the parking meter. A recurring character begins to emerge: a eel vendor, a hunched old man in an eccentrically flower-topped hat. His stooping gait and stillness function to anchor the roiling sea of faces all around him.

The bridge between this sequence and the next is the sound, and indeed the sight, of organ practice at Jacobi Church, whose legendary organ pulls are topped with carved wooden heads, serving here as analogue for the ‘glorious faces’ Roos observes on the streets. The peals of the organ overlay a montage of views of the city, running the gamut from the airport to a park in bloom to half-timbered houses. The organ fanfare heralds a new cycle for the city, one in which the streets are in full flow. Again, in this central ‘panel’ of the film, the rhythms and diversity of the city are articulated through modes of walking. Cutting emphasises juxtapositions: the bobbing heads weaving across a city square, round a flower stall and right past the camera; the masses of grey and brown jackets pierced by a pretty red-head clad in teal amongst the crowd of city workers, who tries to avoid meeting the eye of the camera. Crowds sway and smile in the market as traders sell bananas and sausages; men amble along the cobbles of the red light district, the camera crouched and panning surreptitiously at ground level. An organ-grinder’s monkey dances, visitors inch around the zoo, navvies trudge back from their shift. A sequence in the Stock Exchange is particularly rich in its editing together of the tapestry of movements there: traders dashing round corners and occasionally colliding with each other and almost with the camera, the sound of smart shoes on the stone floor, a close-up of the drumming fingers of a gentleman waiting on a leather bench for — something.

This sequence in Jørgen Roos zeigt Hamburg moves the viewer from streets full of commuters to the red light district, the zoo, the stock exchange and the harbour, all anchored by the voice of the eel vendor.

With three minutes of the film remaining, a second segue occurs. Harbour workers have finished for the day and are drinking beer in a pub. The eel vendor packs up and trudges off, exit stage right. Most suggestive of all, a red carpet is rolled out, there is a trumpet fanfare, and a group of aproned waiters enter a grand space bearing trays of seafood. Cut to the neon of the Reeperbahn, and cars gliding past in the dusk. The third sequence of the film unfolds, but is still interspersed with shots of the old eel vendor climbing the stairs and collapsing gratefully onto his couch. His work is done for the day, but we are now introduced to a range of city dwellers whose shift is just beginning. A theatrical monologue soundtracks a montage of actors applying makeup, musicians taking their seats while smartly-dressed crowds spill into the Staatsoper, and ballerinas warming up behind the curtain. One dancer primes her shoes in the resin box and goes en pointe, the focus on her feet and ankles distilling the film’s recurring interest in feet moving across the city. Shots of exotic dancers fixing their feathers backstage are cheekily followed with a close-up of chickens turning on a spit. The orchestra is now assembled, and the first stroke of the conductor’s baton initiates a dizzying sonic and visual montage of the city at nighttime: glass and light; cars and walkers; lovers embracing by a lake, older women playing cards and knitting; sequinned dancers (now decently covered in white brassieres under their feathers) shimmying on stage, cross-cut with elderly tourists descending from a bus. The diegetic orchestral tones are superseded by a more popular music-hall ditty about Hamburg, and as the song reaches its climax, the light in the house by the harbour winks off, and the film closes.

To see or to show Hamburg?

Some of the content of the film as described above can be traced to interventions by the Filmkreis. Only a small number of revisions to Roos’ draft were requested. One memo signed by committee member hr. Simmet discusses the problem of showing Herbertstrasse in the red light district, but concludes that the images could be included, given that they were shot discreetly in daylight and would be understood only by the initiated (Simmet 1962). On the micro-level, there were requests from members for more attention to details such as the organ in Jacobi Church, and that some of the exotic dancers depicted on the Reeperbahn were thought to be showing too much flesh. More generally, it was pointed out that the original overarching structure of the film — a ship sailing down the Elbe to harbour while city life is ongoing — was unrealistic in terms of temporal logic. Most interesting perhaps is the Committee’s request that the proposed voiceover should be dropped entirely, as this would make it easier to adapt the film for foreign distribution (Filmkreis 1962a). While the film retains some recorded speech such as shouting at the stock exchange, the voices of traders at the fish market, the actors’ monologues, and the gabbling of the eel vendor, such verbiage plays a similar role in the film to the various musical lyrics that dominate: environmental sound and representative variety.

While the titles of A City Called Copenhagen and Oslo put the city at the centre of the picture, Roos’ Hamburg film takes a slightly different tack. In the production files of commissioned films, the question of which title to choose often emerges as a point of contention. The fragments of the arguments recorded in committee minutes are sometimes indicative of the conceptual, artistic and commercial tensions underlying the film project as a whole. In this case, the debate turned on the choice of a verb: sehen or zeigen? The Filmkreis plumped for the former — Jørgen Roos sieht Hamburg (Jørgen Roos looks at Hamburg) — but the filmmaker disavowed this title, explaining that he could not highlight his own role in the project at the expense of his colleagues (Roos 1962b). As a compromise, and to avoid having to resort to perceived banalities such as Impressionen, Kaleidoskop, or In Hamburg…, the verb in the title was altered to Jørgen Roos zeigt Hamburg (Roos 1962c) — Jørgen Roos Shows (or presents) Hamburg. The distinction here would seem to be that the director then assumes the role of tour guide, rather than the origin of an Olympian gaze on the city. For the Filmkreis, it was essential to highlight that the film had been made by the filmmaker to whom their publicity materials referred as ‘one of the best-known, most distinctive and well-regarded short film directors in the world’ (Filmkreis 1962b). Despite his protestations, the filmmaker’s role is to both see and present the cities to the world, and to envision them anew for their residents.

Roos’ Hamburg film met with warm reviews in Germany. As in Denmark, there was a recognition that humour had an important role in promoting the city abroad, but of more interest was the effect of a foreigner’s perspective on the Hamburg. The ‘kaleidoscope’ provided by the film was of interest even to a local, thought one reviewer; Roos had the ‘necessary distance’ on the city to ensure that the fifteen copies sent abroad would hit their mark (Morgenposten 1962). At the 1963 festival of tourist films in Luanco, Spain, Jørgen Roos zeigt Hamburg was awarded a gold medal for best film and silver for best editing. The same year, it won silver at the Bilbao International Documentary Festival (Behnke 1964).

However, the production files also contain some anxious correspondence between its German commissioners about negative reviews in Denmark. One of these came from the poet and cultural critic Klaus Rifbjerg, who expected something more innovative from Roos:

I don’t know if we ought to expect this work to renew documentary film. I only know that one ought to expect something essentially new from Jørgen Roos, who is one of our best, most artistically convincing documentarists and equipped with the best eye. We’re still waiting. (Rif 1962)

OSLO

While Rifbjerg’s critique sets up something of a straw man — what kind of film would have been innovative enough for the notoriously curmudgeonly reviewer? — it does give rise to questions about whether it is a logical impossibility to produce something ‘essentially new’ within the double strictures of a film commission based on an established genre. As outlined above, at the same time that he was working on Jørgen Roos zeigt Hamburg, the filmmaker was also engaged in another project in Oslo. While the latter was also a commissioned film, the remit was flexible enough to allow for — in principle — unfettered artistic innovation. On the other hand, the very circumstances of these productions constitute a unique set of additional constraints. The contemporaneous development of two commissioned films poses logistical issues, though presumably not insurmountable for a busy filmmaker. More interesting is how the Hamburg and Oslo films intersect aesthetically and conceptually, not only with each other, but also with A City Called Copenhagen. All three commissions emphasised the ambition of doing the city film differently; the perceived freshness of the first, itself predicated on its engagement with older city symphonies, is what delimits the possibilities of expression of the next two.

Jørgen Roos’ Oslo begins with the sound of footsteps, echoing through empty city squares and along paths that oscillate between summer and winter 3. Aside from a hardy city worker scattering salt over the tracks ahead of an approaching tram, it is almost two minutes into the eleven-minute film before we encounter any of Oslo’s citizens. Parks benches and city squares alike are empty. But with a pealing of bells from the Town Hall, people enter the picture: initially as a row of feet and knees sitting on a stone bench in the sunshine, given emphasis by a whip pan rightwards to another group of knees. A sequence of vignettes then shows squares packed with cafe guests under parasols, commuters rolling through the streets on trams, the same rows of park benches now populated, queues waiting for fresh prawns off the boat, girls in traditional sweaters and, most importantly, people of all ages scurrying or strolling through the city. So far, pace the emphasis on summer versus winter already discussed, the camera’s interest in the infinite variety of walkers is hard to distinguish from the Hamburg film.

However, two-and-a-half minutes into Oslo, there is an ontological shift. A shot of a glimmering ring of water unexpectedly freezes into a still image. This is followed by two further stills: the crowds on the park benches, and a group of shoppers frozen in motion in the street. This cuts to an exploration of a set of murals in Oslo City Hall by the painter Per Krohg, showing Oslo city life around a decade earlier. The murals are given voice by non-diegetic shouts, a baby’s cries, and children playing. The camera then returns to live-action footage to document passers-by anno 1962. A similar trope is used a few minutes later to introduce a montage of the city’s treasure trove of sculpture. This time, a stunning shot of the City Hall from the window of a construction crane (echoing the use of the unfinished SAS hotel elevator in the Copenhagen film) freezes, and the crane driver’s face is echoed by that of a sculpture. The camera offers a litany of stills and pans over works by Gustav Vigeland and other local sculptors, primarily in Vigeland’s own sculpture park.

As with the eel vendor in Hamburg, a character swims out of the mass of people. She is a dark-haired young woman, at first just a face in a crowd of passers-by striding through the summery park. But her transposition to the same park in winter singles her out, and she appears again in more intimate staged shots as a typist, as sitting in a grill bar window seat with a glass of juice shyly glancing at the young man next to her, typing some more with her headset on. Editing hints that an ensuing set of images may be the woman’s own daydreams: more sculptures of children, dancing women depicted in the woodcarvings in the courtyard of the City Hall, Edvard Munch’s sketches of a dark-eyed woman cross-cut with the young woman applying a perfect flick of black eyeliner. The young man, too, reappears and takes on a quasi-narrative role. He seems to be an elevator attendant, and his mind wanders to showcase another kind of art in Oslo: Viking ships, the Kon-Tiki and Fram vessels, and thence to a speedboat which he pilots, looking astern to the dark-haired water skier he is towing. A clock chimes, and both young people finish work for the day. Shop shutters come down, end-of-shift sirens wail, statues of working men are seen. The dark-haired woman and the blond man both walk through the park and as their paths cross, the film freeze-frames the near-encounter. A montage of romantic sculpture intersects with the two of them lying entwined by a campfire, a shot of criss-crossing rail tracks, and a sudden scream from the woman on a boat. The frame unfreezes and they walk past each other.

Jørgen Roos’ Oslo film ends with a narrative experiment centring on the notion of paths crossing, and explores some of Oslo’s statuary in the process.

On one level, this romantic interlude can be read as a self-conscious nod to Arne Sucksdorff’s city symphony Människor i Stad (Rhythm of a City, Sweden, 1948), which brings a young couple together in the black-and-white, summery city. On another level, though, if Sucksdorff’s love story is suggestive of patterns of fate and order, Roos seems more interested in the chaos of the city. The couple should meet — their paths physically cross repeatedly, and they dream similar dreams — but the images of them together seem to be only a possible or parallel future. The closing minutes of Oslo are so randomly constituted as to be suggestive of a dive into the chaotic temporal and spatial variety of the city. After the couple fail to meet, the anonymous city takes over the tale once more with a selection of old and new architecture, the shoes of a random man, a series of sculptures and carvings of Norwegian men from the Viking age, boat prows, city streets, Golden Age paintings of nature, sketches of the city, a dissolve from a painting of a city yard to a shot of the same location, and a final series of shots of Ibsen’s grave, the Oslo fjord, and a bucolic scene of sheep just outside the city limits.

The manuscript originally drafted by Roos in collaboration with the poet Eiler Jørgensen expresses the tension between possible worlds or narratives in terms of the theme of dream versus reality. With the first freeze-frame on the quayside, the voiceover would ask:

Are they living, these people in Oslo?

Are they living in the now…sitting on the quay and dangling their feet in the water and spitting out prawn shells? Are they living in the here and now?

Or is it their secret that they are dreaming about living? Is it the city of Oslo’s secret that it is a city that dreams, lives in dreams and for dreams…about the past and the future, about the moment that was just here and the moment that is to come…a city where the real is unreal and the unreal is real? (Jørgensen and Roos 1962: 1)

Woven into the infinite variety of this city is the nature of the image itself and the plastic arts. In Eiler Jørgensen’s voiceover, the notion of reality is explicitly connected to art, in a passage about a nameless artist who dreamt of transforming his visions of people into reality, until one day, his visions stood there carved in granite and cast in bronze (Jørgensen and Roos 1962: 3). In adopting the freeze frame as a visual and narrative trope, Oslo also draws attention to the moving image as film and its own status as representation, as mediation.

Jørgen Roos’s Oslo was sponsored by a very particular constellation of city authorities. A distinctive aspect of the cinema industry in Norway has been the domination of the sector by local government. Oslo Kinematografer (Oslo Municipal Cinemas) was the result of the City of Oslo’s takeover of all cinemas in the city in 1925; by the late 1930s, the Norwegian municipalities were involved in all aspects of production, distribution and exhibition of films in the country (Solum 2016: 179, 185). Between the end of the Second World War and the early 1960's, Oslo Kinematografer had produced 92 short documentaries on Oslo’s nature, culture, commercial life and local government. Five tourist films had been produced in collaboration with Reisetrafikkforeningen for Oslo og Omegn (The Oslo Travel Association) (Engh 1963e).

This sustained relationship must be seen in the light of the long career of Alvhild Hovdan (1904-1982) as the head of Reisetrafikkforeningen, a position she held for some forty years from 1932. In the year before taking up the post, Hovdan shot and directed two short films: Hallo Oslo! (in parts I and II), and Norske Kulturpersonligheter (Norwegian Cultural Personalities; The films can be viewed in connection with the article Rushprint Redaksjonen 2017). She was thus Norway’s first female film director. Hovdan also worked in Stockholm in various roles in the film industry, and seems to have maintained the connections over time (Hanche n.d.; Rushprint Redaksjonen 2017).

In late June 1960, a circular was sent to Norwegian short film producers inviting proposals for a new short promotional film about Oslo, which would be funded and produced as a collaboration between Oslo Kinematografer and Reisetrafikkforeningen. Eight manuscripts were received before the deadline.

One of the submitted manuscripts preserved amongst the correspondence is indicative. Signed with the (presumably) nom de plume Thor med Hammeren, it features a voiceover by a young female hitchhiker from England. The film opens with a close-up of her ‘pene dameben’ (lovely legs) walking at the roadside, and she is picked up by a lorry driver called Thor, who invites her to “Jump on board, baby!’. She wanders around in the city, allowing for various montages of sailing in the Oslo Fjord, the view from Holmenkollen, shopping in the city centre, and Vigeland Park. Thor takes her on an evening boat tour and a cycle trip the next day, and presents her with ‘a real Norwegian gift’ to take home: a pair of reindeer horns (Thor med Hammeren 1960).

When forwarding the entries to Hovdan, her counterpart at Oslo Kinematografer, Arnljot Engh, remarked that while several of the manuscripts contained useable material, the authors seemed very committed to showing the traditional sights. Notably, he continued: ‘I must admit that I feel what is missing is a striking and artistic idea that can elevate the film into something quite special, like the Danish film about Copenhagen’ (Engh 1960b) — that is, A City Called Copenhagen.

Hovdan was of the same opinion, and proposed an alternative plan: that the two organisations should collaborate to commission three short films about Oslo by leading Danish, Norwegian and Swedish filmmakers. At the same time, she proposed increasing the ring-fenced funding to a level commensurate with A City Called Copenhagen, around 100,000 kroner. This proposal was revised in cooperation with Engh to take account of the political difficulty for Oslo Kinematografer of spending a tranche of its limited funds to support Danish and Swedish filmmaking. Oslo Kinematografer would thus sponsor two short films by Norwegian directors, while Reisetrafikkforeningen would sponsor the Danish and Swedish productions. The reasoning made explicit here was that funding for tourism, though also public money, could logically be used to promote Oslo to foreign audiences (Engh 1961). The budget was set at 60,000 kroner per film, though the two foreign directors seem to have been given a slightly higher allowance of 65,000 kroner (Reisetrafikkforeningen 1962).

Hovdan’s strategy naturally sparked interest not only in Norway, but also in Sweden and Denmark. She was happy to expand on her idea to a Swedish journalist, for example, explaining that the Oslo films needed “a fresh and unconventional view” to attract foreign audiences. For that reason, the filmmakers had been given the most flexible of briefs: the films had to be in colour and 12-15 minutes in length, but otherwise the approach was up to them. And the highest standards were to be encouraged, and extra publicity generated, by establishing a prize fund of 20,000 kroner for the best film, as judged by a small committee (Holmberg 1962).

The two Norwegian directors appointed were Ulf Balle-Røyem and Ivo Caprino. The Swedish director of choice was Per Gunwall, and the Dane was, of course, Jørgen Roos. With their services secured, it was a priority to arrange stays in Oslo for the two non-Norwegian directors and their camera operators. The pan-Scandinavian air operator SAS had agreed to provide free transport. Reisetrafikkforeningen was able to organise hotel accommodation for one week so that the directors could get to know the city, and for a further period of three weeks for the shoot itself (Hovdan 1962, Reisetrafikkforeningen for Oslo og Omegn 1962). To judge by the weather in parts of the finished film, and by Roos’ schedule in Hamburg, his Oslo film must have been primarily shot in August or September 1962.

Upon receipt and review of the manuscript in late July, Engh makes clear that the principle of giving the filmmakers free hands had been entirely serious. Writing to Reisetrafikkforeningen, he comments that the synopsis indicates that the films will be made with ‘artistic nerve’ and that the only problem might prove to be achieving parity between the images and the voiceover. But Oslo Kinematografer will not make any comment on the manuscript, he says, because the filmmakers are to have artistic freedom (Engh 1962).

A distinctive feature of the publicity surrounding the Oslo films was the prize of 20,000 kroner awarded to the best one, as decided by a small jury. The judges were the Norwegian film critic Mrs Aud Thagaard, the head of the Danish Tourist Board Laurits Hvas, and the Swedish art critic Dr Gustaf Näström. They met in mid-March 1963 to view the films and to deliberate. Thereafter, the films had a public premiere and the prizewinner — the Norwegian was announced at the Scala cinema in Oslo on 20 March 1963, a Wednesday afternoon (Engh 1963e). The winner was the Norwegian Ulf Balle-Røyem, with Kontraster i en by. On 7 June the same year, the presentation of the four films was repeated in Copenhagen at the Palads Cinema, also introduced by Oslo Mayor Rolf Stranger.

Jørgen Roos produced a new version of Oslo a few years after the competition, replacing Claes Gill’s reading of Eiler Jørgensen’s prose poem with new music by composer Per Nørgård. This version won the gold medal at the 1968 La Spezia film festival, plus a prize for best cinematography. Hovdan and Engh travelled to Copenhagen to celebrate the award with the filmmaker (Se og Hør 1968). The revision brought Oslo into line with Jørgen Roos zeigt Hamburg in that both films now mediated the experience of the city primarily through music rather than words, with speech bodying forth in the films only as ambient sound.

Oslo Byarkiv has made all four short films from the 1962 competition, as well as other films about the Norwegian capital, available via a dedicated site, oslofilmer.no (Oslo Byarkiv 2018), and has also screened them at cultural festivals in recent years. Together with a range of other films from different eras about the city, Roos’ Oslo thus forms part of a growing digital resource allowing the citizens of Oslo to witness their city grow and change through the decades, and to compare and contrast artistic responses to it as a place and as a destination.

Weaving places together

Their story begins on ground level, with footsteps. They are myriad, but do not compose a series. They cannot be counted because each unit has a qualitative character: a style of tactile apprehension and kinesthetic appropriation. Their swarming mass is an innumerable collection of singularities. Their intertwined paths give their shape to spaces. They weave places together. (de Certeau 1984: 97)

Jørgen Roos’ Oslo begins with the sound of footsteps, echoing through empty city squares and along paths that oscillate between summer and winter. In the screenplay draft, the impersonal ‘man’ (one) elides any distinction between the footsteps of the filmmaker, the viewer, or the people yet to appear on screen:

One walks through the streets of Oslo. One looks at houses and trees, at towers and statues. One listens to the sounds of bells and trams, senses scents, notices the feel of asphalt and cobbles through the soles of one’s shoes. (Jørgensen and Roos 1962: 1)

Of his Copenhagen, Hamburg and Oslo shorts, Jørgen Roos’ Oslo is the film in which walking is narratively thematised — both in the original voiceover, and in the later version through the sound of footsteps. Starting a film with a city divested of its walkers is profoundly disorienting. As the voiceover continues, ‘houses and streets and towers and parks and statues are only a set. The people, the city’s residents, give the set life and meaning’. In Oslo, walking brings the dark-haired young woman and the blonde man together in terms of spatial proximity, but in a park full of scurrying office workers, it is not enough to kick-start their story together. In Jørgen Roos zeigt Hamburg, walking is the physical manifestation of the temporality of the city: something is always about to happen, and people are on their way there. In A City Called Copenhagen, we have to look harder through the assembled crowds to find the walkers, but they are there: exploring the harbour in search of art, or sweeping the streets.

Walking, then, in these films, becomes a way to ‘weave places together’, to borrow from de Certeau. None of the films seems to harbour any ambition to mediate a legible map of the city, preferring instead to juxtapose areas in a kaleidoscopic way. Rather, the movement of crowds and of individuals is used to edit the cities together: parks versus city streets, dock workers versus city gents, morning shift versus night shift. And, importantly for sponsored films commissioned by the ‘technocratic power’ which de Certeau sees as permeating the city, walkers as ‘an innumerable collection of singularities’ can resist that power. The Catch 22 for Roos’ trilogy is, of course, that the ‘technocratic power’ has commissioned films that emphasise the everyday, the democratic and the informal.

Precisely because the films were commissioned by organs of the state in Denmark, West Germany and Norway, archival materials have preserved traces of the workings of that ‘technocratic power’ in its engagement with these film projects. Committee minutes, correspondence and comments on drafts reveal something of the competing interests, opinions, and varying levels of knowledge about what film could depict and how it disseminated knowledge; they emphasise time and again that there was respect for the artistic integrity of the filmmaker, even if this is rooted in the instrumentalist ambition to leverage reputation and skill in the service of promoting the city. The ‘us versus them’ divide for which de Certeau’s vision of power in the city has been critiqued does not hold water when the everyday compromises and minutiae of bureaucracy are laid out on the archive table.

Accessing such files requires the researcher to visit the relevant archives in the respective cities. Like Roos, I knew Copenhagen, but not Oslo or Hamburg. In walking though the city streets to unfamiliar archives, listening to new sounds and smelling new scents — learning to walk on Oslo’s icy pavements and acclimatising to German — I had cause to consider the importance of the filmmaker’s exploratory trips to Norway and Germany. What is not recorded in the production files are those first, tentative encounters with the unfamiliar city — ‘feeling the asphalt and cobbles through the soles of one’s shoes’ — and the process of distilling those encounters into the screenplay. If Jørgen Roos zeigt Hamburg and Oslo revolve around walking, perhaps it was precisely because this most ‘elementary form of experience of the city’ (de Certeau 1984: 93) must have been their condition of possibility.

Notes

1. All translations from Danish, Norwegian and German sources are my own.

2. Parts of this section are adapted from chapter 10 of my recent monograph on Danish informational cinema (Thomson 2018)

3. The description in this article is based on the revised version of the film without a voiceover, though reference is made to the original screenplay draft including voiceover.

The author wishes to thank staff of the Danish Film Institute, Oslo Byarkiv and Staatsarchiv Hamburg for their kind help and expert advice.

References

Andersen, A. M. (1966), (letter to Reisetrafikkforeningen for Oslo og Omegn, 14.10.1966), Oslo Film C, Oslo Byarkiv.

Anonymous (1963), (letter to Rolf Stranger, n.d., ‘Besøk av Jørgen Roos…’), Oslo Film C, Oslo Byarkiv.

Behnke (1964), (letter to Herbert Peipes, Internationes, 2.12.1964), Bestellung der Hamburg-Films, Mappe 3457, Staatsarchiv Hamburg.

de Certeau, Michel (1984), ‘Walking in the City’, in The Practice of Everyday Life, trans. Steve Rendall, London< Berkeley, New York: University of California Press, pp. 91-110.

Det Forenede Sampskibs-selskab (1963), (letter to Ulfhild Hovdan, 11.6.1963), Oslo Film C, Oslo Byarkiv.

Easthope, Anthony, ‘Cinécities in the Sixties’, in The Cinematic City, ed. David Clarke, London: Routledge 1997/2005 ebook, pp. 131-140

Ekstrabladet (1960), ’København set af et talent’, Ekstrabladet 3.2.60, ‘A City Called Copenhagen’, Sagsmapper, SFC-særsamling, Det Danske Filminstitut.

Engh, Arnljot (1960a), ‘Produksjon av kortfilm om Oslo’, 29.6.1960, Oslo Film C, Oslo Byarkiv.

Engh, Arnjlot (1960b), (letter to Alvhild Hovdan, 5.9.1960), Oslo Film C, Oslo Byarkiv.

Engh, Arnljot (1961), (letter to Rolf Stranger, 4.10.1961),Oslo Film C, Oslo Byarkiv.

Engh, Arnljot (1962), (letter to Reisetrafikkforeningen for Oslo og Omegn, 29.7.1962), Oslo Film C, Oslo Byarkiv.

Engh, Arnljot (1963a),

Engh, Arnljot (1963b), (letter to Mme Margot Cassagne of JANCO, 12.7.1963), Oslo Film C, Oslo Byarkiv.

Engh, Arnljot (1963c), (letter to Mme Stavenow Cassagne of JANCO, 8.11.1963), Oslo Film C, Oslo Byarkiv.

Engh, Arnljot (1963d), (letter to Reisetrafikkforeningen for Oslo og Omegn, 21.6.1963), Oslo Film C, Oslo Byarkiv.

Engh, Arnljot (1963e), ‘Konkurrencen om den bedste Oslofilm’, letter to Rolf Stranger, 19.3.1963), Oslo Film C, Oslo Byarkiv..

Engh, Arnljot (1965), (letter to Reisetrafikkforeningen for Oslo og Omegn, 4.6.1965), Oslo Film C, Oslo Byarkiv.

Engh, Arnljot (1966), (memo to Oslo Kinematografers Styre, 15.12.1966), Oslo Film D, Oslo Byarkiv.

Filmkreis (1961a), (letter to Jørgen Roos 5.9.1961), Bestellung der Hamburg-Films, Mappe 3456. Staatsarchiv Hamburg.

Filmkreis (1961b), (schedule for Jørgen Roos visit, 5.12.1961), Bestellung der Hamburg-Films, Mappe 3456. Staatsarchiv Hamburg.

Filmkreis (1962a), (Comments on Jørgen Roos’ draft, 30.4.1962), Bestellung der Hamburg-Films, Mappe 3456. Staatsarchiv Hamburg.

Filmkreis (1962b), (Draft text for film programme, 12.11.1962), Bestellung der Hamburg-Films, Mappe 3456. Staatsarchiv Hamburg.

Gold, John R. and Stephen V.Ward , ‘OF PLANS AND PLANNERS: documentary film and the challenge of the urban future, 1935–52’, in The Cinematic City, ed. David Clarke, London: Routledge 1997/2005 ebook, pp. 61-85

Grierson, J. (1966) (1947), ‘First principles of documentary’, in F. Hardy (ed.), John

Grierson on Documentary, Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, p. 145–56.

hamburg.de (n.d.), ‘Geschichte des Staatsarchivs’, http://www.hamburg.de/bkm/geschichte/ (accessed 6 May 2018)

Hanche, Øivind (n.d.), ‘Alvhild Hovdan’, nordicwomeninfilm.com, http://www.nordicwomeninfilm.com/person/alfhild-hovdan/ (accessed 7 May 2018).

Hartmann (1962), (vehrmerk 18.1.1962), Bestellung der Hamburg-Films, Mappe 3456, Staatsarchiv Hamburg.

Holmberg, Göran (1962), ‘Svensk gör reklamfilm för norska huvudstaden’, Aftonbladet, 30.5.1962, Oslo Film C, Oslo Byarkiv.

Hovdan, Alfhild (1962), (letter to per Gunwall, 29.5.1962), Oslo Film C, Oslo Byarkiv.

Hovdan, Alfhild (1966), (letter to Oslo Kinematografer, 22.9.1966), Oslo Film C, Oslo Byarkiv.

Irgens-Jensen, Åse (1964), (letter to Oslo Kinematografer, 17.6.1964), ‘Balle-Røyem, Ulf, Kontraster i en by, 1962-1979’, Gamle Kortfilmer, Oslo Byarkiv.

Jørgensen, Eiler and Jørgen Roos (1962), ‘Byen hedder Oslo’, ‘Samarbeide med Reisetrafikkforeningen’, Oslo Film C, Oslo Byarkiv.

Kristensen, Sigvald (1954), (letter to Københavns Overborgmester), 5.11.1954, Korrespondance og notater, ‘A City Called Copenhagen’, Filmsager, SFC, DFI.

Kristensen, Sigvald (1959) (untitled document signed SK), ‘A City Called Copenhagen’, Sagsmapper, SFC-særsamling, Det Danske Filminstitut.

Lynch, K. (1960), The Image of the City, Cambridge: MIT Press.

MacDonald, S. (1997), ‘The city as the country: the New York City Symphony from

Rudy Burckhardt to Spike Lee’, Film Quarterly, 51: 2, pp. 2–20.

Morgenposten (1962), ’11 Minuten Hamburg’, Morgenposten 5.12.1962, Bestellung der Hamburg-Films, Mappe 3457. Staatsarchiv Hamburg.

Morris, Brian (2004), ‘What we talk about when we talk about ‘Walking in the City’’, Cultural Studies, 18:5, 675-697, DOI: 10.1080/0950238042000260351

Oslo Byarkiv (2018), ‘Oslofilmer’, oslofilmer.no, accessed 14 May 2018.

Polezynski, Ernst (1966), (letter to Oslo Kinematografer, 4.7.1966), Oslo Film C, Oslo Byarkiv.

Price, Brian, ‘Moving through Images’, in Taking Place: Location and the Moving Image,

ed. JOHN DAVID RHODES, ELENA GORFINKEL, Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press. (2011). Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5749/j.cttts485.16, pp. 299-316

Raynsford, Anthony (2011), ‘Civic Art in an Age of Cultural Relativism: The Aesthetic Origins of Kevin Lynch's Image of the City’, Journal of Urban Design, 16:1, 43-65, DOI: 10.1080/13574809.2011.521019.

Reisetrafikkforeningen for Oslo og Omegn (1962), ‘Avtale (med Minerva Film A/S, dated 14.4.1962), Oslo Film C, Oslo Byarkiv.

Rif. (Klaus Rifbjerg?) (1962), ‘Noget om Hamburg. For en indbudt kreds vistes i går Jørgen Roos’ nye dokumentarfilm’, Politiken 19.12.1962, A City Called Copenhagen, Filmsager, SFC, DFI.

Roos, Jørgen (1959), ‘Filmen om København’, Korrespondance og notater, A City Called

Copenhagen, Filmsager, SFC, DFI.

Roos, Jørgen (1962a), ‘Vorschlag zu einem 35mm Farbfilm, Eastmancolor, Spieldauer ca 12 min. IN HAMBURG IST WAS LOS’, Bestellung der Hamburg-Films, Mappe 3456, Staatsarchiv Hamburg.

Roos, Jørgen (1962b), (letter to Filmkreis, 23.10.1962), Bestellung der Hamburg-Films, Mappe 3456, Staatsarchiv Hamburg.

Roos, Jørgen (1962c), (letter to Filmkreis, 24.10.1962), Bestellung der Hamburg-Films, Mappe 3456, Staatsarchiv Hamburg.

Roos, Jørgen (1963), (letter to Alvhild Hovdan, 9.2.1963), Oslo Film C, Oslo Byarkiv.

Rushprint Redaksjonen (2017), ‘Var Alfhild Hovdan Norges første kvinnelige filmregissør?’, Rushprint, 27.11.2017, https://rushprint.no/2017/11/var-alfhild-hovdan-norges-forste-kvinnelige-filmregissor/ (accessed 7 May 2018).

Se og Hør (1968), ‘Norsk hæder til dansk film’, Se og Hør, 16.2.1968, ‘Oslo’, Udklipsarkivet, Det Danske Filminstitut.

Simmet, (comments on Jørgen Roos’ draft, 20.9.1962), Bestellung der Hamburg-Films, Mappe 3456. Staatsarchiv Hamburg.

Solum, Ove (2016), ‘The Rise and Fall of Norwegian Municipal Cinemas’, in Hjort, Mette and Lindquist, Ursula (ed), A Companion to Nordic Cinema, London and New York: Blackwell, pp. 179-198.

Stein, E. (2013), ‘Abstract space, microcosmic narrative, and the disavowal of moder- nity in Berlin: Symphony of a Great City’, Journal of Film and Video, 65: 4, pp. 3–16.

Thomson, C. Claire (2018), Short Films from a Small Nation: Danish Informational Cinema 1935-1965, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Thor med Hammeren (1960), ‘Arbeidstitel: “Den koselige by” eller “Den vennlige by”’, Oslo Film C, Oslo Byarkiv.

vest (1959), ‘Kbh anskuet fra utraditionelle vinkler’, Information 12.12.59, ‘A City Called Copenhagen’, Sagsmapper, SFC-særsamling, Det Danske Filminstitut.

Suggested citation

Thomson, C. Claire (2018): Walking in Copenhagen, Hamburg and Oslo – Planned and Lived Space in Jørgen Roos’ Early-60's City Symphonies. Kosmorama #272 (www.kosmorama.org).