Carl Th. Dreyer’s films have been subject to a wide range of critical interpretation, broadly grouped under four thematic headings. First, scholars initially considered his work along autobiographical lines. Ebbe Neergaard’s A Film Director’s Work (1940)1 was the first detailed examination of his films, arguing (1963, 44) they bear strong autobiographical traits and the influence of D.W Griffith’s Intolerance (1916), most clearly Blade af Satans Bog (Leaves from Satan’s Book, 1921). Neergaard’s book was influential, raised Dreyer’s profile and facilitated his return to filmmaking with Day of Wrath (1943). Martin Drouzy’s two-volume biography, Carl Th. Dreyer, born Nilsson (1982), is the most detailed examination of Dreyer’s life and similarly argues that Dreyer’s traumatic childhood impacted his work. Second, there are critics (for example Ken Kelman, 1965) who propound a straightforward reading of the films, focused on Dreyer’s often unusual plots. Third, a strain of scholarship focuses on Dreyer’s spiritual preoccupations, as depicted through his female protagonists in La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc (1927) and his last three major films, Vredens Dag (Day of Wrath), Ordet (1955) and Gertrud (1964). Tom Milne (1971, 31), for example, argues that “the Dreyer heroine is adored; as a temptress who sins and causes to sin against the man-made laws of puritanism, she is made to suffer; and subconsciously wields a power that is inbred, incalculable, purely supernatural.” Jean Sémoulé’s (1962, 155) interpretation is religious, emphasising the female protagonist’s journey from “condemnation…to redemption in the exaltation of human will associated with God.” Raymond Carney (1989, 71) similarly highlights Dreyer’s preoccupation with the “adventures of the spirit…the inner realms of eventfulness.” Lastly, at odds with this spiritual preoccupation are the analyses of Philippe Parrain, David Bordwell and Edvin Kau, who take a formalist approach. As Bordwell (1981, 3) argues, “the films’ primary importance is not thematic but formal and perceptual.”Their attention focuses almost exclusively on Dreyer’s cinematography, mise-en-scène and editing. In sharp contrast to the three other schools of criticism cited above, Bordwell concludes the films are ultimately displays of auteurship that resist being read. He describes (1981, 190), for example, Gertrud as “a film striving to become empty.”

This essay focuses on Day of Wrath, the eleventh of Dreyer’s fourteen films. A story of witchcraft, illicit love and multiple murders, the plot is presented in a more straightforward manner than in his two previous films, La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc (1928) or Vampyr (1932), both of which deal with similar themes. Spectatorial credibility is less stretched than in Ordet – in which a protagonist is resurrected from the dead – and patience less challenged than in Gertrud, in which a non-naturalistic cinematography appears to function in opposition to a naturalistic drama. Bordwell’s assessment (1981, 117) that “Day of Wrath is probably Dreyer’s most popular film” summarises consensus that it is the most accessible of his mature œuvre. Perhaps not surprisingly, critical attention on the film has focused on the portrayal of the leading figure, Anne, frequently interpreted as one in a long line of protagonists – from Victorine in his first film, The President (1919), to Gertrud – who “suffer the slings and arrows of outraged society” (Milne 1971, 35) in their attempt to find self-expression and love. Film theorists, on the other hand, who frequently cite Jeanne d’Arc, Vampyr, Ordet, and Gertrud, have little to nothing to say about Day of Wrath. Siegfried Kracauer in Theory of Film (1997, 82) only references the film’s “intrinsically artificial universe.”

This essay argues that scholarship, in considering the portrayal of Anne as Dreyer’s primary concern, simplifies the film’s narrative and overlooks aspect of composition which function both with and against the diegesis. It disregards that Dreyer’s prime thematic consideration in Day of Wrath is less the individual (i.e. Anne), but instead institutional structures and the damage they inflict on all the protagonists depicted. As Dreyer himself (letter, quoted Drum 2000, 91) wrote, “Perhaps I can help you to an understanding of the common idea of most of my films. I have always been against intolerance wherever I met it: national, political, religious or in everyday life…If you watch my films closely, you will discover that the action mostly takes place on a background of intolerance.” Social critique is a leitmotif across Dreyer’s œuvre, and this thematic so clearly portrayed in Day of Wrath is seen nascently in his first films, The President and Leaves from Satan’s Book, remaining a preoccupation through to his last, Gertrud. Milne (1971, 92) is the only critic to acknowledge that Dreyer “spent fourteen films denouncing the cruelties, prejudices, superstitions, hypocrisies and dogmatic assertions that make up so great a part of the history of so many established churches.” Other scholars, in largely viewing the films in isolation, have overlooked common narrative threads and how their depiction progresses through changing cinematic styles and techniques throughout Dreyer’s œuvre. The pivotal importance of Day of Wrath in this context is, however, acknowledged by Jean-Louis Comolli (quoted by Mark Nash 1977, 58) who describes it as “a focal point in an œuvre to which is it manifestly the key…Day of Wrath is one of the very rare films to answer the classical definition of tragedy…these are not ‘characters’ confronting each other but two antagonistic forces: against the forces of life are ranged those of the repressive system.”

While Day of Wrath continues Dreyer’s preoccupation with the critique of social norms and forms, the film differs markedly in its limpid lucidity. The film’s clarity in thematic and style stands in sharp contrast to his Expressionist-tinged films of the 1920s and 1930s, particularly Jeanne d’Arc and Vampyr, also to his last two films which revert to a spiritual thematic, albeit with markedly different cinematography. This singularity of Day of Wrath has been insufficiently considered to date. The most illuminating way to ‘read’ Day of Wrath I contend is as allegory, a methodology less successfully applied to Dreyer’s other films. Michael Murrin in The Veil of Allegory (1969, 102) refers to three modes of literary criticism: literal; moral; and allegorical, with the latter category “including a diversity of interpretations, generally involving political, cosmological, psychological and theological levels.” It is most appropriate in this context to consider Day of Wrath, as political/social allegory. Whilst a cosmological reading, as argued by Paul Schrader (1972, 112) – “throughout Dreyer’s films there runs a consistent thread of ambiguity: whether art should express the Transcendent or the person who experiences the Transcendent” – is validated, both by subject matter and presentation, it is not the focus here. Instead, this essay considers how Day of Wrath functions as social allegory, in its representation of the “repressive system” cited above by Comolli. Day of Wrath depicts general socio-institutional issues of universal relevance, Tocqueville’s "tyranny of the majority" and its well-structured oppression of minorities. Anchoring the social allegory is the historical specificity of the narration, particularly its depiction of the post-Reformational church. Angus Fletcher, in Allegory: The Theory of a Symbolic Mode (1964, 5) argues that “Allegory in the Middle Ages came to the people from the pulpit, it comes to the modern reader in secular form.” This implies a double-layering on Dreyer’s part in creating an allegory of the pulpit, while the pulpit – the Church’s representatives depicted in the film – was itself deploying the myth of witchcraft as a means of repression.

The allegorical reading of the film proposed here is supported by historical contextualisation, predicated on archival work, tracing the film’s genesis and placing it inside it inside the prevailing literary and artistic debates of its epoch: the essay’s title is a reference to Aesthetics and Politics, the collection of essays by Ernst Bloch, Georg Lukács and Bertolt Brecht, likely influences on Dreyer. This interpretation of the film as social allegory focuses on the film’s key thematic, the repression of the individual by an institution of state. It considers not just the “political” but also the “aesthetic,” namely the filmic devices deployed, often with great subtlety, by Dreyer. The stylisation of the film through mise-en-scène, cinematography and deployment of sound is crucial to the functioning of the film as social allegory, not least as it serves to elevate the thematic’s relevance beyond the specific historicity of the depiction to a universal, timeless plane, relevant to contemporary and future audiences.

Genesis

Dreyer commenced work on the script of Day of Wrath in early 1942, following an extended period of difficulty. His previous film, Vampyr, had faced challenges with financing and with sound and was a financial and critical failure. Dreyer subsequently entered a mental institution (Drum 2000, 165; Drouzy 1982, vol. 2, 147; Kau 1989, 248), although few details are known. Furthermore, according to Drum (2000, 166), his daughter was lobotomised in the 1930s. Dreyer was forced to return to journalism, initially as a film reviewer for the Danish tabloid B.T. This only lasted three months as his reviews were considered too negative and literary.

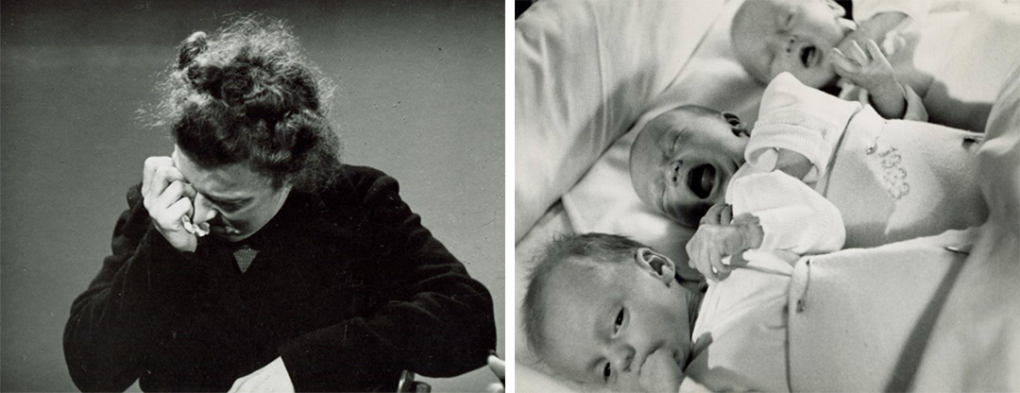

The path back to filmmaking, and Day of Wrath, came in 1940 from Ministeriernes Filmudvalg (Ministries’ Film Commission). Its brief was to produce shorts that could replace German propaganda newsreels shown ahead of the lead film. Nordisk agreed to Dreyer making a short, and on the proviso that it was delivered on time and to budget, it would fund Day of Wrath. Dreyer produced Mødrehjælpen (Good Mothers, Fig. 1) in the summer of 1942, a short urging pregnant women in financial or social difficulties not to consider abortion. Dreyer’s court column in B.T. and Good Mothers could be considered evidence of a concern with the socially disadvantaged (see Drouzy 1982, vol. 2, 160): in Good Mothers, the institution concerned is solely portrayed in a positive light, unlike in Day of Wrath.

The short was made in full accordance with the term of his contract, yet Nordisk would not honour the contract for Day of Wrath, which was then taken over by Palladium.

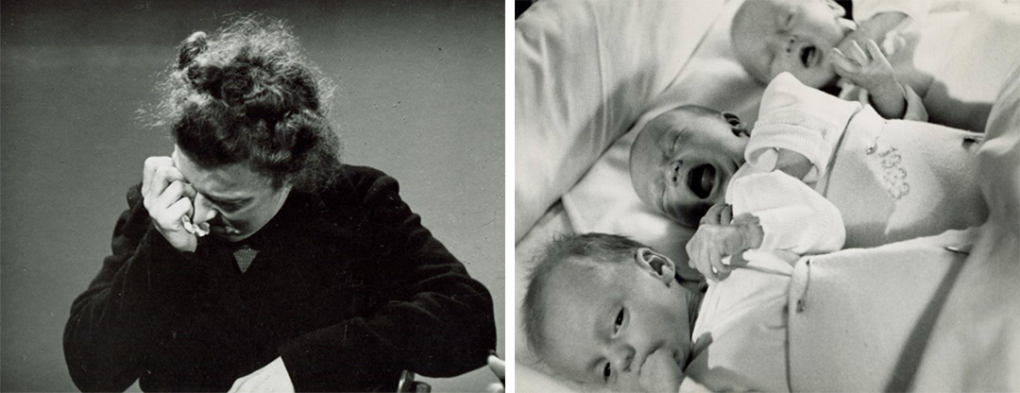

Day of Wrath premiered at the World Cinema in Copenhagen on 13 November 1943. Newspaper reviews were almost uniformly negative – “Deadly boring” (see Kau 1989, 283) – focusing on the film’s slow pacing which many audiences found ‘intolerable’ (Bordwell, 140): Berlingske Tidende (14 November 1943, 57) stated the “tempo stole the life from Day of Wrath”. Berlingske Aftenavis (15 November 1943, 3) called it Dreyer’s own “Day of Wrath: a missed opportunity for Danish cinema” (Fig. 2 right). The only two positive reviews came from Børsen (22 November 1943, 25), a “notable work of art” and the Kopenhagener Soldatenzeitschrift (5 December 1943, Fig. 3), the German newspaper for the occupying troops in Denmark (!), praising the film’s artistic qualities, and suggesting that Dreyer would find greater success outside Denmark.

Day of Wrath was only released internationally after the end of WWII, receiving a considerably more positive response. The New Statesman (30 November 1946) stated that “Day of Wrath, by its truthfulness and nobility of style, leaves impressions, not of panic, but of beauty.” English-speaking critics looked beyond the measured tempo and gloomy thematic – The Sunday Dispatch (24 November 1946) wrote “the entire plot is so steeped in gloom that one is inclined to wonder if the burning of the witch was intended to be the light side of the story” – to focus primarily on its visual beauty and expert composition. Roger Manville concluded his review in the BFI (1948, vol. 4, 4) describing the film as “a classic example of a meticulous technique both in camera and sound, which is always the servant of character and situation, not its master.”

Literary Influences on Dreyer

A consideration of Day of Wrath as social allegory benefits from considering Dreyer’s position within Scandinavian modernism and the influence on him of prevailing schools of literary criticism. These influences have to date been broadly overlooked, since Dreyer was generally considered to have pursued a solitary path: Børge Trolle (1955, 2) for example argues that “he quite independently reached such artistic levels,” and Milne (1971, 10) similarly argues that his films “simply exist.”

As a student, Dreyer attended Georg Brandes’ lectures on Main Currents in Nineteenth Century Literature (Drouzy 1982, vol.1, 100). Brandes was acknowledged as the theorist behind the “Modern Breakthrough” of Scandinavian culture, influencing Ibsen and Strindberg and the playwrights used as source by Dreyer for Day of Wrath (Hans Wiers-Jenssen), Ordet (Kay Munk) and Gertrud (Hjalmar Söderberg). “Modern Breakthrough” elided into the modernism movement, which reached its peak in Scandinavia during the 1940s, around the release of Day of Wrath. Modernism was an aesthetic response to processes of modernity, including politics and psychology. Its influence can be seen in Day of Wrath’s formal experimentation, the limitation of language (a lifelong preoccupation of Dreyer), mythological images of women as ‘monsters’ (witches), and the ambiguity/non-closure of the film’s ending.

Dreyer’s interest in social issues and aesthetics can be considered in light of the debate in 1938 between Ernst Bloch and Georg Lukács over Expressionism and Naturalism. Their dispute was part of a wider debate presenting different attempts to conceptualise the social function of art. Both worked within a Marxist ideological frame of reference – not a primary concern for Dreyer – yet their differing views on the relationship between aesthetics and politics is of relevance and is linked to an allegorical reading of Day of Wrath. Bloch argued art should serve as a tool for social change and saw one of the key qualities of Expressionism as “drawing attention to human beings and their substance, in their quest for the most authentic expression possible” (Aesthetics and Politics 2020, 18). His reference to Expressionism’s “experiments with montage and other devices of discontinuity” (2020, 16) has clear parallels with Dreyer’s earlier films, particularly Leaves from Satan’s Book, Michael (1924), Jeanne d’Arc, and Vampyr.

Lukács’ response to Bloch’s essay, “Realism in the Balance” (1938), opposes both Bloch and Expressionism, arguing that “the Expressionists thought they were conveying the ‘essence of things’, whereas in fact they revealed their decomposition” (2020, 38). His essay defines three schools of contemporary writing: the openly anti-realist apologists of existing capitalist society (Expressionism); ‘avant-garde literature’ characterised by its increasing distance to realism; lastly, realism, represented by writers such as Thomas and Heinrich Mann. This third school was for Lukács the genuine avant-garde (2020, 26): “What counts is the social and human content of the avant-garde, the breadth, the profundity and the truth of the ideas that have been ‘prophetically’ anticipated.”

A comparison of the opposing stances of Bloch and Lukács suggests that the Day of Wrath marked a significant departure for Dreyer, away from the influence of Expressionism in films up to Vampyr towards the “avant-garde” realism espoused by Lukács. Lukács’ call for “a closed and integrated reality” (2020, 26) is immediately apparent in the universe Dreyer creates in Day of Wrath. Dreyer’s achievement with the film was the same as the authors cited by Lukács (2020, 35), “to penetrate the laws governing objective reality and to uncover the deeper, hidden, not immediately perceptible network of relationships that go to make up society.” Lukács concludes (2020, 56) by stating that “only when masterpieces of realism past and present are appreciated as wholes, will their topical, cultural and political value fully emerge.” As allegory, this is precisely what Dreyer achieves in Day of Wrath, with its creation of “realism past and present” through meticulous scenography, carrying both “cultural and political value.”

“Before the Court of the Lord”: Dreyer’s Critique of the Church

The following section examines Dreyer's depiction of the Church as the principal oppressor of the individual, even of those carrying out its work. Mise-en-scène, cinematography and sound are deployed not only to intensify this thematic, but to create an aesthetic which imparts a timeless monumentality and sculptural quality onto the film.

Thematic

Murrin (1969, 74) states that “allegory is intimately associated with the society in which the poet writes: it must be explicable in social terms.” Society’s portrayal in Day of Wrath is restricted to religion, presented as the sole functioning, thereby dominant institution. Other societal structures, for example economic or political, are excluded.

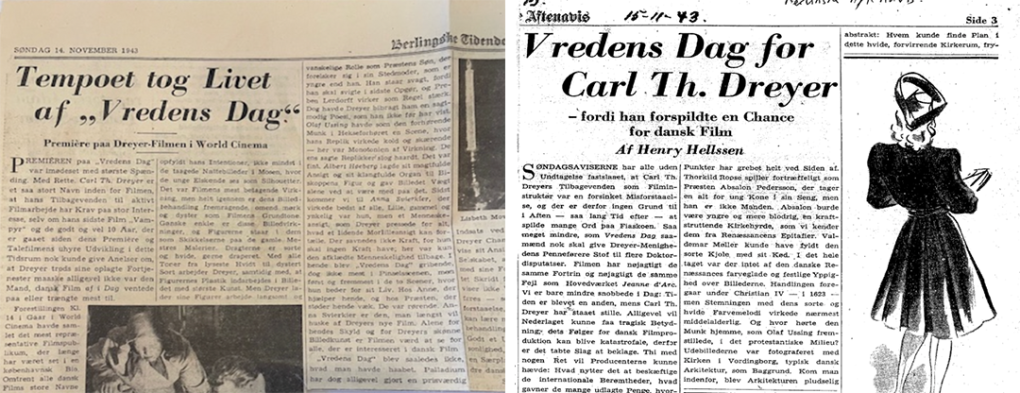

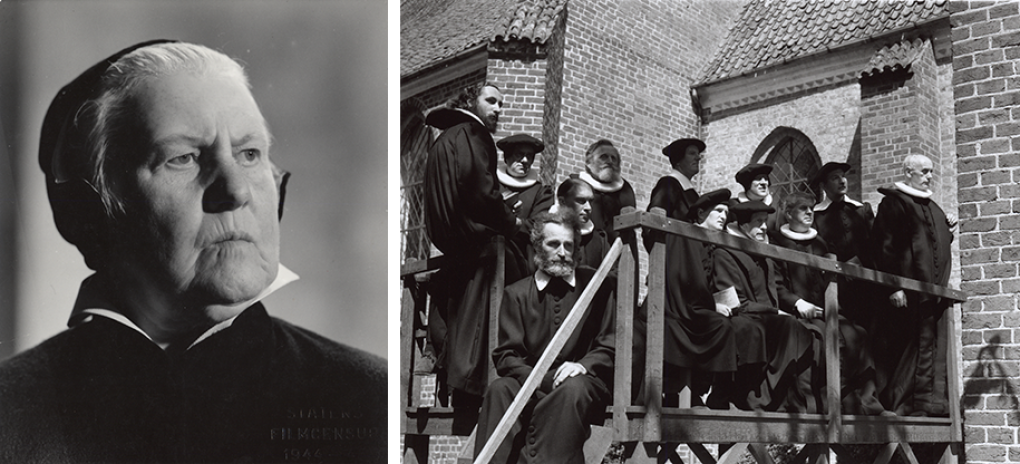

The film’s portrayal of the Church is uniformly negative, focussing on its preoccupation with interrogation, torture, execution and ceremony. There is no depiction of any festive ritual nor suggestion of redemption or eternal life. In a revision to his source, Hans Wiers-Jenssen’s Anne Pedersdotter (1908), Dreyer deleted the final scene (1917, 87) where all surviving protagonists sing the psalm “Iam maesta quiescat querela” around Absalon’s bier. The elision of a text referencing the restoration of life after death demonstrates Dreyer’s determination to refute any positive reading of the religious messaging in the film. Even the two ‘named’ representatives of the Church, Absalon (Anne’s husband) and Master Laurentius fear eternal damnation for their acts. It is striking that the representatives/enactors of the repressive system – the churchmen – are not depicted as intrinsically evil or sadistic, but merely carry out the system’s dictates in good faith: they are also victims of the status quo they help perpetuate. It is an ecclesiastical system steeped in hypocrisy, evidenced in inscriptions into the Church ledger of Herlofs Marte “having been tortured to the glory of God” (Fig. 4, left), leading her to make a “beautiful confession” (Fig. 4, right), and finally being “happily burned”. Ole Storm (Dreyer 1970, 21), in the Introduction to Four Screen Plays, rightly refers to Dreyer’s “pungent, uncompromising criticism of religious self-righteousness … where the portrayal of the priesthood has a satirical edge worthy almost of Daumier.”

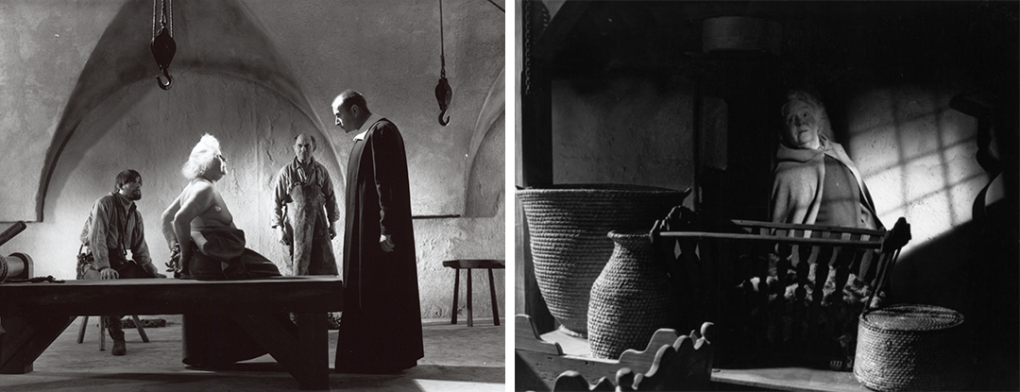

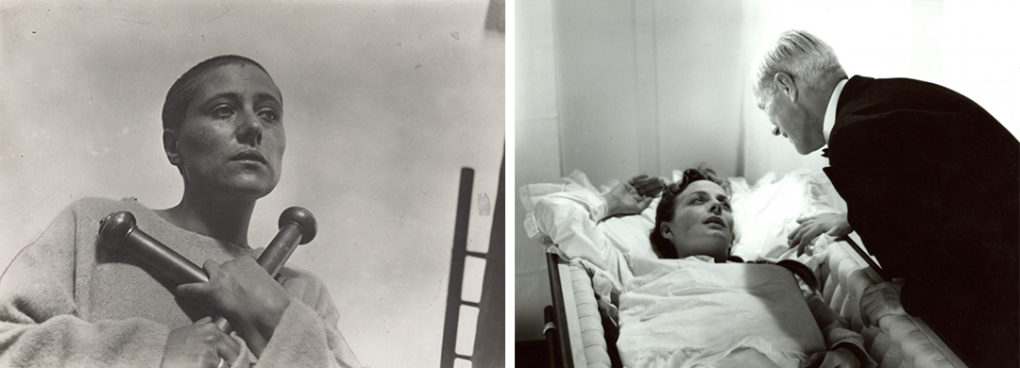

The Church propels the narrative of the film and the protagonists appear unable to resist this momentum: as Elsaesser notes (see Doxtater 2024, 108), “The world is closed, and the characters are acted upon.” Herlofs Marte's tormenting by the Church dominates the narrative in the first part of the film, from her capture, to trial and burning at the stake. Whereas Wiers-Jenssen in Anne Pedersdotter only alludes to torturing, the depiction in Day of Wrath of her torture and forced confession constitutes the film’s lengthiest and arguably most memorable scene (Fig. 5, left). Dreyer thereby makes visual and explicit the Church as a force of violence and subjugation. Another revision to the source was to commence the plot with the ‘secondary’ protagonist, Herlofs Marte, and her attempted escape (Fig. 5, right): in contrast, the play’s opening scene is an argument between Anne and her mother-in-law, Merete. Through this revision, Dreyer deprioritises Anne and, more importantly, sets up the parallel between Herlofs Marte’s fate and that to befall Anne (Dreyer does not actually portray Anne being burned at the stake, given his intent on retaining an open ending for the film). Both the film’s patterns of repetition – one of the first lines of the film is Sidse Skrædder’s “Who are they hunting now?” – and its open ending are typical of allegory. As Murrin (1969, 100) writes of allegory: “Every end is another beginning. One myth leads into another. Allegorical plots habitually end inconclusively.” Dreyer’s intent to highlight the replication of fate is further demonstrated by titling the film Day of Wrath, rather than copying the name of the source. All other films directly sourced by Dreyer from extant works of literature, such as Prästänkan (The Parson’s Widow, 1921), Glomdalsbruden (The Bride of Glomdal, 1926), Ordet and Gertrud share the source’s title. Instead, the title revision for Day of Wrath directs the spectator’s attention to the multiple forces of ‘wrath’ depicted in the film, rather than projecting Anne’s fate as the film’s primary interest.

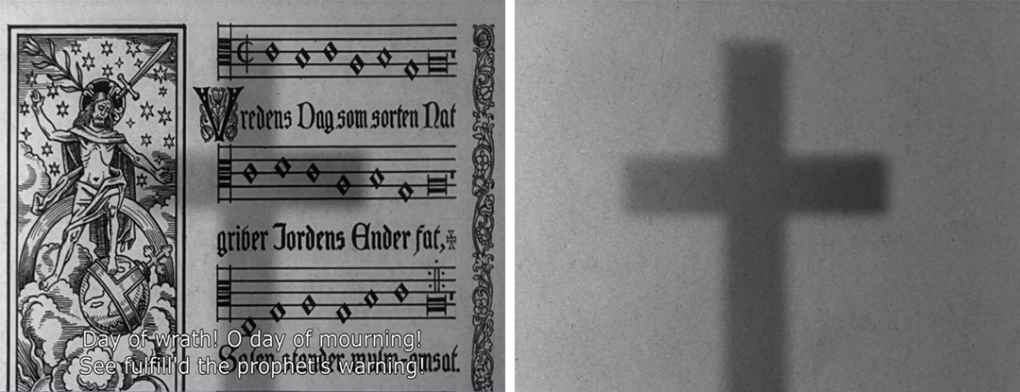

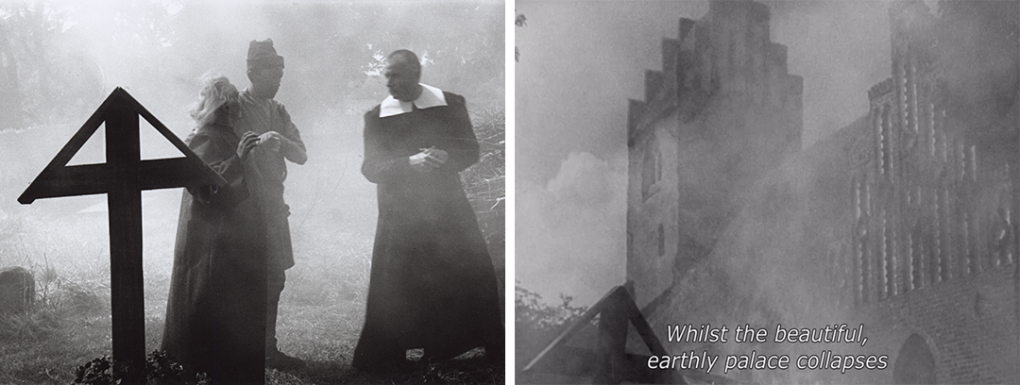

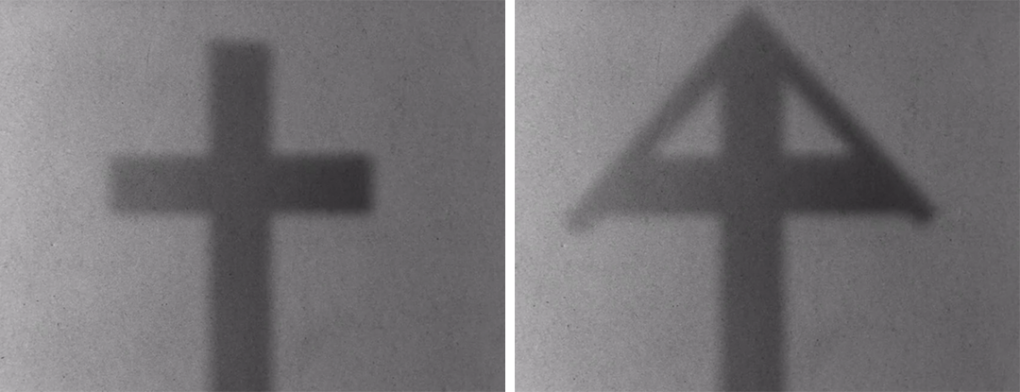

The Church not only ‘controls’ the narrative but also acts as a double-frame for the film itself, reinforcing the impression of its omnipotence. Dispensing with opening credits, the film commences (Fig. 6) with the first ecclesiastical frame, the text of the Dies Irae. The scroll, on which the text is written, is presented with a superimposed crucifix (an obvious additional reference to the Church and its link to death in the ensuing plot) and accompanying woodcuts. Eight verses of the Dies Irae are presented pictorially, ending with “Day of wrath, from Satan’s strap” before the image fades. The verses – not a direct translation of the Latin original, but an even bleaker reworking by the Danish poet, Paul la Cour – introduce motifs and images portrayed during the film, such as the “flames will fall upon us” (verse 2), and the act of judgement, “shown before the Court of the Lord” (verse 5). Both motifs reference acts of the Church depicted in the film, namely Herlofs Marte’s trial by Absalon, Master Laurentius and the assembled clergy (the “Court of the Lord”), and her burning. The scroll therefore programs the ensuing plot causally and chronologically, anticipating and mirroring what is depicted in the main body of the plot. The scroll’s unrolling is ‘interrupted’ in the eighth verse, to be reintroduced at the end of the film, thereby providing a formal and ecclesiastical closure. The crucifix initially superimposed on the text, subsequently introduced into the plot as a leitmotif, is finally ‘liberated’ from the text (Fig. 6, right), to stand alone in what Bordwell (1981, 140) describes as “eternal fixity…the stopping point of meaning.” Anchoring the opening and closing scene of the film, reappearing frequently as the plot unfolds, the cross is a symbol of Church-imposed death, and the denial of resurrection. As in the earlier The Parson’s Widow, the final sign of the cross underscores the repressive system depicted in the film, an “uncanny, ghostly pattern of repetition” (Kau, quoted by Mark Sandberg 2006, 38).

The image of the Dies Irae unscrolling at the commencement of the film ‘bleeds’ into a quill being dipped into the inkpot (Fig. 7, left), then a hand writing Herlofs Marte’s arrest warrant, to be signed by three “worthy clergymen.” This image is the second framing device deployed. The ‘bleed’ links two images of text, one finished, the other in the process of creation. They serve as official record for posterity as presented by an anonymous Church (both texts are authorless). Whilst the fifth verse of the Dies Irae scroll states, “Lo! The book exactly worded/wherein all hath been recorded,” the viewer is made aware from the subsequent presentation of an official document, the writing of Herlofs Marte’s death warrant (Fig. 4, right), that this is not, in fact, an objective recording (“exactly worded”), instead a manipulated truth serving as self-justification by the Church. This double framing device is a refinement of a trope from Jeanne d’Arc, in which Dreyer deploys only a single frame of written record; both films, however, separately depict the process of inscription, the transformation of a protagonist tortured by the Church into a manipulated, sanitised public record: within Day of Wrath, Absalon is depicted (Fig. 7, right) inscribing the death warrant, subsequently the death record of Herlofs Marte. He therefore becomes the personification of false record.

Whereas the Dies Irae text is timeless, the arrest warrant is specifically dated, historically anchoring the ensuing plot. Murrin (1969, 105) argues for the importance of both historical specificity and timelessness/myth in allegory: “Poets habitually modelled…their allegories on historical events, generally refracting the truth of specific occurrences through the distorting lens of euhemeristic myth.” Wiers-Jenssen’s play literally adheres to this “truth of specific occurrences”: the play was based on the life of Absalon Pedersønn Beyer (1528-75), rector, author and diarist, whose wife was tried twice for witchcraft and burned at the stake in Bergen in April 1590. Dreyer retains the authenticity of Wiers-Jenssen’s plot but brings it forward from 1574 in the play to 1623. This re-periodisation corresponds to the high point (1617-1625) of burning for witchcraft in Denmark (see Egholm 2009, 250). By bringing the plot forward by fifty years, Dreyer gains greater storyline distance from the Reformation, forceably introduced to Norway in 1537 by the Danish king, Christian III. The play (Act 2, Scene 1) portrays a synod dinner at which the priests accuse each other of popery. Dreyer excises this scene completely, also the subsequent religious discussion between Absalon and his son. Theological disputes would have acted as distraction to the film’s plot: Dreyer’s intention instead is to present a unified church, one less concerned with theological debate than the mechanisms of power.

Utilising the historical witchcraft thematic, Dreyer positions the film within collective memory. Dreyer was one of several artists in the 1930-40s to see the potential in using a historical/mythical setting to project a contemporary thematic. As Trolle (1955, 5) writes, “It is not quite an accident, that Middle Age subjects and surrounds are now occupying modern literature and drama with an increasing frequency.” Awareness of the audience’s ‘acceptance’ of witchcraft as historical fact allows the artist to convey a broader, a-historic truth. As Murrin (1961, 84) writes, “Through memory, the poet breaks out of the world of time into a kind of extratemporal viewpoint, from which past and future are seen to form different parts of a common human pattern. He drew upon history, the record of public events, exploiting the memory of humanity itself” (my italics).

The counterfoil to Day of Wrath’s subject matter – the formalised oppression of the individual – is the portrayal of nature. As Sémoulé (1962, 98) argues, its depiction in Day of Wrath assumes an importance only matched in The Parson’s Widow and The Bride of Glomdal. Nature represents an Edenesque state where emotions and sexuality are untrammelled and Anne’s and Martin’s relationship is consummated. Images of cornfields and lovers in boats (Fig. 8, left) match those previously utilised in Præsidenten (The President, 1919), Der var Engang (Once Upon a Time, 1922) and The Bride of Glomdal. Similarly, the shadows of swaying leaves were anticipated in Good Mothers (see Thomson 2015, 54). At the height of the passion between Anne and Martin, nature briefly manages to penetrate the gloomy rectory with images of the trees seen through the windowpanes (Fig. 8, right). This, however, proves short-lived. Instead, the ecclesiastical force and thematic foreshadowing of death quickly penetrate nature’s idyll, implied by the first image of a horse in the field with Anne and Martin (Fig. 9, left) being replaced by the horse-drawn cart filled with wood for Herlofs Marte’s funeral pyre (Fig. 9, right). Nature remains an alien space to protagonists embodying the Church’s repression: Merete and Master Laurentius are never depicted outside and Absalon is almost killed by a storm when journeying from the rectory to administer Master Laurentius’ last rites. In this respect nature plays an additional role in an allegorical interpretation of the film, acting as more than just a visual foil or relief from the gloomy interior scenes. As Fletcher (1965, 6) argues in Allegory: The Theory of a Symbolic Mode, “…sublime scenic description is the carrier of thematic meaning. Scenery is always more than a tacked-up backdrop. It is a paysage moralisé, and heroes act in harmony with or in violent opposition to that scenic tapestry.”

In thematic, therefore, Dreyer depicts an ecclesiastically controlled universe driven by a collective mechanism of power and repression, preoccupied with the legacy of a whitewashed account of its actions. Cycles of oppression, revenge and death are self-perpetuating: Martin will become his father, Absalon, as a force of priestly oppression, and Anne will share the fate of Herlofs Marte; Herlofs Marte’s threat of revenge is implied as cause in the deaths of Absalon, Master Laurentius and likely Anne – “If I shall burn, so shall Anne!” Furthermore, Merete is revenged for Absalon’s death by accusing Anne of witchcraft, and Anne believes Absalon will be revenged for his death by hers. The plot is a distillation of cruelty with the Church as instigator, yet not even its representatives are spared its wrath: as Absalon foresees, “My death has been decided on.”

Aesthetics

In addition to source material revisions cited above, Dreyer deployed mise-en-scène, cinematography and sound to intensify the thematic of the oppression of the individual.

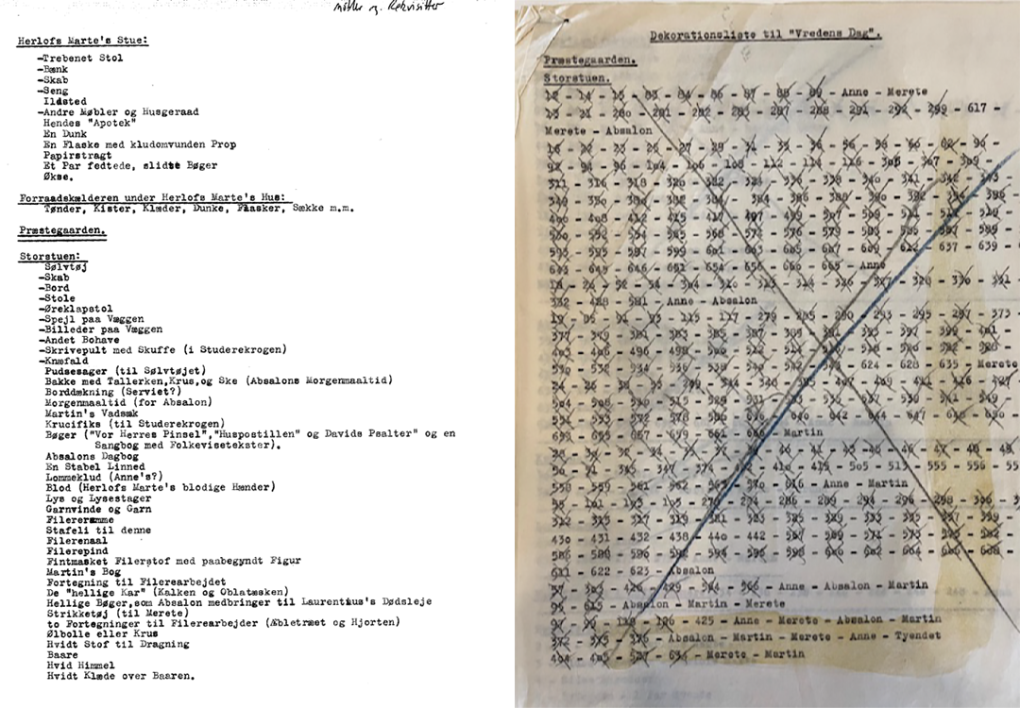

1) Mise-en-scène: Preben Lerdorff Rye, the actor who played the role of Martin, referred (Drum 2000, 192) to “Dreyer’s fantastic preparation, for instance, he searched half a year to find a soap dish that would be right for the film.” Once the set was prepared, Dreyer and the scenographer, Lis Fribert, removed all but the few props they considered essential. Fig. 10 gives a helpful example of his working style. The left-hand image from the Dreyer archive details all the props he was considering for the first two scenes of the film; the right-hand image details how the vast majority were ultimately rejected.

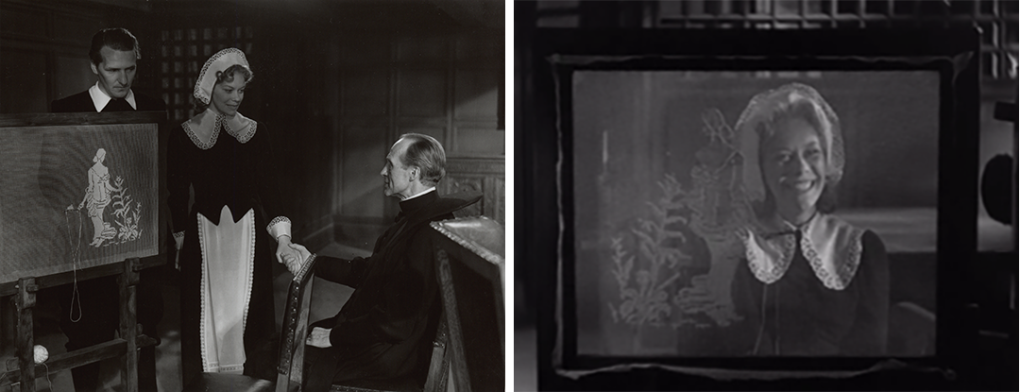

Dreyer’s primary intent with the mise-en-scène was no doubt historical accuracy, making credible the plot’s unfolding. Kracauer (1960, 82) refers to the historical accuracy of Day of Wrath giving the film the “traits of a documentary.” Nonetheless, the setting in Day of Wrath differs to his other films, particularly Ordet (Fig. 11, left) and Gertrud, where protagonists are anchored by a backdrop that appears specific to them. Here his intention was that “the personality of the actors (would be) reflected in all the details that surround them” (Parrain 1967, 12). This was not, however, the case in Day of Wrath, where the décor is sparser and more impersonal. The film’s only prop offering a direct reference to a protagonist is the embroidery rack on which Anne stitches the image of the “Virgin in the Apple Tree”. The matching text is from the Song of Solomon, quoted several times during the film. It embodies Anne’s awakening sexuality and rare moment of happiness (Fig.12, right). The presentation here marks what Doxtater (2024, 95) refers to as a “metacinematic moment, when the frame of her needlework nearly coincides with the frame of the film itself, a frame within a frame,” acting as a (domestic) counterweight of the double ecclesiastical framing of the film previously referenced. The absence of domestic comforts – which cannot alone be explained by the different period in which Day of Wrath is set compared to Ordet or Gertrud – acts both to depersonalise the presentation and to elevate the protagonists into a historically non-specific timeframe.

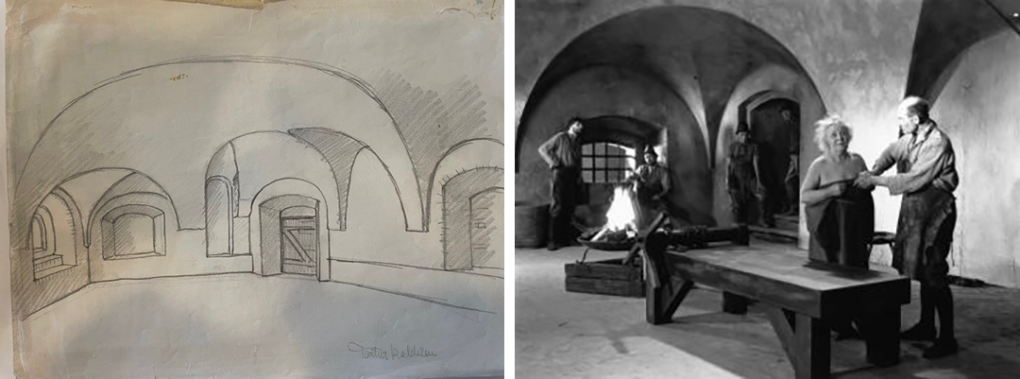

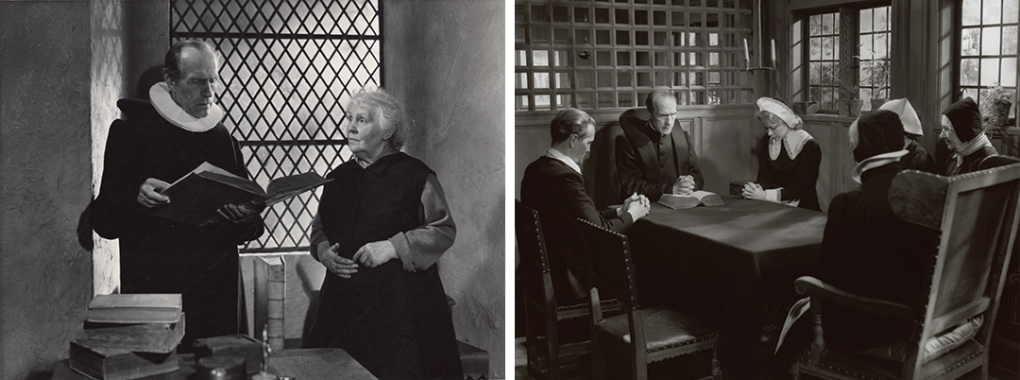

The architecture deployed in the film works in a similar manner to make abstract the film’s periodisation. Fig. 13, left shows Dreyer’s preparatory sketch for the torture chamber scene, and Fig. 13, right the corresponding still from the film. This setting deployed in the film’s longest scene is ‘timeless’, taking the subjugation/torture scene out of any historical specificity, helping it resonate to a contemporary audience. This is true of other scenes set in church chambers, as when Herlofs Marte vainly pleads for Absalon’s assistance. Separately, Dreyer utilises the physical structure of the sets to present an ‘ecclesiastically controlled’ frame: the repeated use of crossbars extends from multiple scenes in the church (Fig. 14, left) and torture chamber into the domestic space of the rectory (Fig. 14, right), thereby also ‘containing’ the protagonists within their domestic environment. The protagonists appear restrained by this framing device in all the internal sets (Fig. 15), contrasting with the untrammelled openness of the nature scenes.

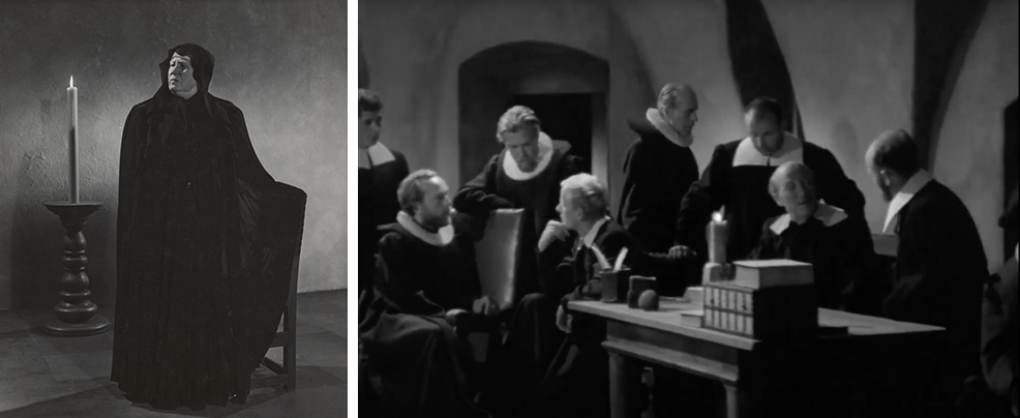

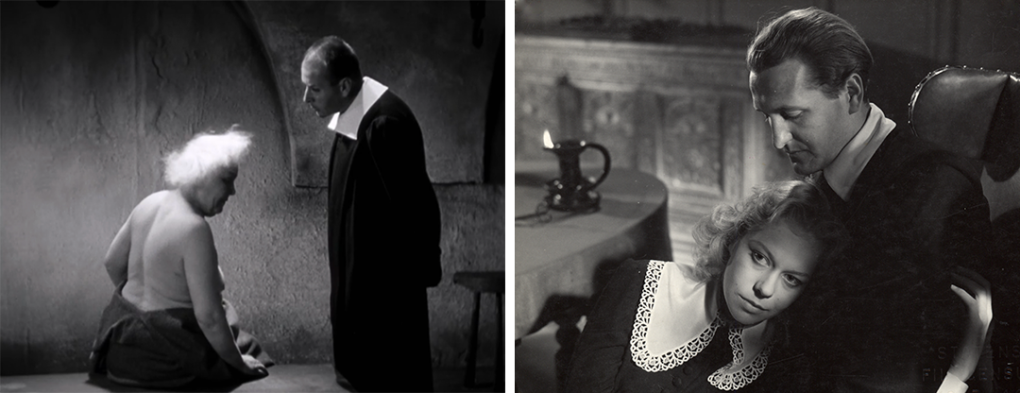

The oppressive force of the Church is also conveyed by the protagonists’ clothing. Here, too, Dreyer initially ensures historical accuracy: his working papers include pages of notes and photographs of seventeenth century costumes. Not surprisingly, critics have likened the costumes to those seen in Dutch interior paintings (André Bazin, quoted by Nash 1977, 15), specifically by Rembrandt (Drum 2000, 195; Agee 1963, 303) and von Wasserhoven (Sémoulé 1962, 102). However, the severity of the costumes extends beyond such historical accuracy to become emblematic of the repressed state of their wearers. As Carney (1989, 151) argues, “The churchmen have sacrificed their distinctive expressive identities to institutional systems of signification.” In a shot from the final scene (Fig. 16, left), Merete appears as a timeless demon, and the assembled representatives of the Church (Fig, 16, right) as a similar repressive force witnessing the torture and confession scenes. Raymond Durgnat observes the impact of this presentation (1966, 50), “All the respectable bourgeois citizens are clad in long black angular garments which encase their bodies like coffins.” There are only two (female) exceptions, both representing a threat to the church. First, Herlofs Marte, whose hair remains untamed throughout. Her bare flesh during the torture scene (Fig. 17, left) appears in stark contrast to her capturers, entombed in their vestments. Truffaut (1980, 48) refers to “the most beautiful image of female nudity in the history of cinema – the least erotic and most carnal nakedness – the white body of Herlofs Marte, the old woman burned as a witch.” The second exception is Anne: the subtle transformation of her collar, cap and hair as her relationship with Martin blossoms, reflects her growing rebellion against the ossified life and control of the rectory. Finally, following the consummation of their relationship, Anne (Fig. 17, right) removes her cap, and wears her hair completely free over a decorative lace (previously plain) collar.

2) Cinematography: Cinematography offered Dreyer further scope to support the film’s thematic of repression. First, the camera serves to deny the protagonists agency. Day of Wrath marks a departure from the ‘omniscient’ and privileged position of spectatorship that had characterised Dreyer’s films up to and including Jeanne d’Arc. It is the viewer rather than lead protagonist who is put in a position of omniscience, for whom the parallelisms that are built between the characters become increasingly apparent. One technique to represent this is through cutting, when protagonists are visually ‘replaced’ by others, such as the dissolve which ‘replaces’ Herlofs Marte with Anne, and then vice versa, highlighting the similarities between them and ultimately their fate. Point-of-view shots that would have granted the protagonist agency are replaced by an autonomous camera that fails to fix the viewer onto one protagonist’s perspective. Anne, in particular, is deprived of the omniscient perspective usually afforded the principal protagonist. Large sections of the plot unfold without her presence or knowledge. Her deprioritising is underscored when she exits the camera frame on numerous occasions while the other protagonists generally remain; otherwise, the camera lingers to present a vacant space. Anne, like Herlofs Marte, is depicted as an outsider, often an isolated observer, for example in the cathedral (Fig. 18, left) ahead of the torture scene, and inside the rectory during Herlofs Marte’s execution (Fig. 18, right). This gives the impression of a wider force propelling the narrative, namely the Church, particularly during the Herlofs Marte section of the plot’s two-part structure: by the time narrative attention focuses primarily on Anne in the second section of the film, events are unfolding under their own, inevitable momentum.

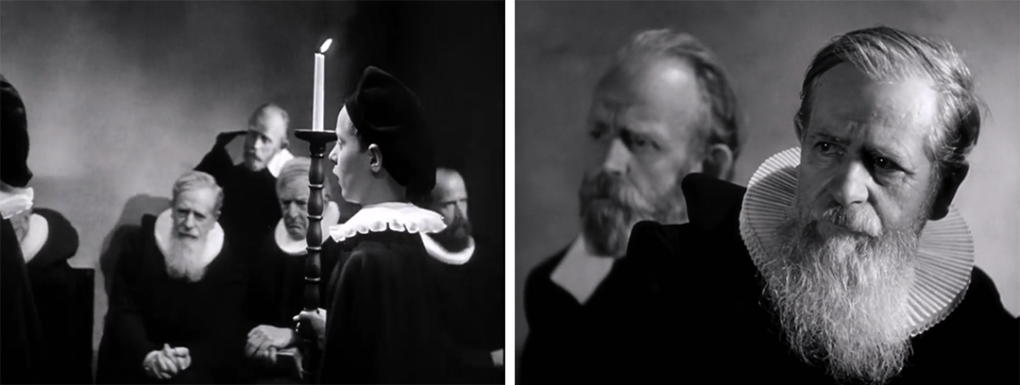

Second, camera movement not only defeminises the two protagonists who stand in opposition to the Church, but also makes associations between the forces of power operating in the film. An example is the onset of the final scene: the camera travels with the young choir – the ‘voice’ and embodiment of the Dies Irae – to depict the assembled church elders responsible for Herlofs Marte’s torture and immolation, settling finally on the group around Absalon’s bier. This group witnesses Merete accusing Anne of Absalon’s murder, the first step to Anne’s own immolation.

Third, by eschewing point-of-view shots, Dreyer elevates the gaze within the film to a mode of control. This is even embodied into the dialogue of the film, with frequent reference between the protagonists of the gaze. For example, the line “I am seeing you through tears” is said three times during the film, by different characters and at very different stages of the plot. Merete (Fig.19, left) is the first protagonist to look in a distinctly intense manner, fixing Anne through her scowl, trying to control her. Thereafter the power of the gaze is centred on the Church, both in the form of individuals – Absalon when Herlofs Marte is pleading for her life – and as a collective (Fig. 19, right), observing her burning. Lastly, the Church is visually associated with death, as Herlofs Marte is taken to the pyre (Fig. 20, left) and as the backdrop whilst she burns to death (Fig. 20, right), with the accompanying words “Whilst the beautiful, earthly palace collapses” a bitterly ironic juxtaposition by Dreyer.

3) Sound and music: Day of Wrath was Dreyer’s first film in which dialogue and sound were fully incorporated. He had been characteristically cautious in adopting this new technology and was, for example, highly critical of the use of background music in Hollywood films (Neergaard 1963, 84). However, in the 1933 essay, “The Real Talking Film” he noted the potential of sound for purification and concentration (1973, 54).

In terms of sound effects, Dreyer restricts himself to incorporating gusts of wind at moments of tension, strikingly in the storm scene when Absalon departs to administer Master Laurentius’ last rights. Sound is even used as part of the “concentration process” referenced above from Dreyer’s essay to replace image in propelling the plot. This calls into question Milne’s (1971, 27) contention that “even in sound films his vision is wholly visual.” We hear, for example, rather than see Herlofs Marte being captured whilst hiding in the rectory attic. Similarly, we ‘only’ hear her being tortured: by the time the camera pans to include her within the torture chamber, she is already making her confession. Anne hears rather than sees Herlofs Marte’s immolation, having turned away from the rectory window. Sound is therefore deployed to depersonalise the forces of authoritarian violence. Separately, the dialogue throughout the film runs almost entirely at low volume, with little modulation in pitch: As Sémoulé (1962, 100) remarks, words are “being whispered, murmured, yet ripped by cries.” There are only two occasions during the film when voices are raised: first, when Merete expresses her disgust at Anne’s sexuality and the age difference between the married couple – the impact of the spoken Danish with its explosive consonant in “Jeg synes det er SKAMLØST” (my capitals) is entirely lost with subtitles; second, when Herlofs Marte screams at Absalon just before her burning and threatens to denounce Anne. Before they communicate meaning, Nash (1977, 77) argues, Dreyer’s dialogues are “modulations, musically determined…the raw state is the child-like scream of the old woman (Herlofs Marte), penetrating from the attic into the presbytery below.”

Dreyer deftly employs sound to intensify the impression of the film’s thematic on the spectator. It is encoded both acoustically and visually into the film. The first sound heard, before the visual of the unfurling scroll, is of bells. They reappear throughout the film at key moments: during Herlofs Marte’s attempted flight from her pursuers; Anne watching the immolation – the fact that the bells are associated with Anne before the camera portrays Herlofs Marte at the stake becomes a foreshadowing of Anne’s own fate; and in the final scene around Absalon’s bier. They act as metric pulse, representing the Church’s oppressive power, penetrating both private (Herlofs Marte’s home) and public sphere, beyond the immediate ‘physicality’ of the church itself. The next sound heard is the dramatic symphonic music, based on the Dies Irae motif. The Dreyer archive includes a letter he wrote to the distribution company in Denmark, instructing the opening music to be played as loudly as possible during screenings, to give the impression of a “powerful dance of death.” This opening music is repeated, less intently, when Anne enters the church, and at the end of the film. An association is therefore created between terror (the effect of the opening bars) and the Church as institution, even before the depiction of Herlofs Marte’s torture and forced confession. Another association is created – this time, between the Church and death – when the theme from the opening bars accompanies the film’s closing image of the crucifix.

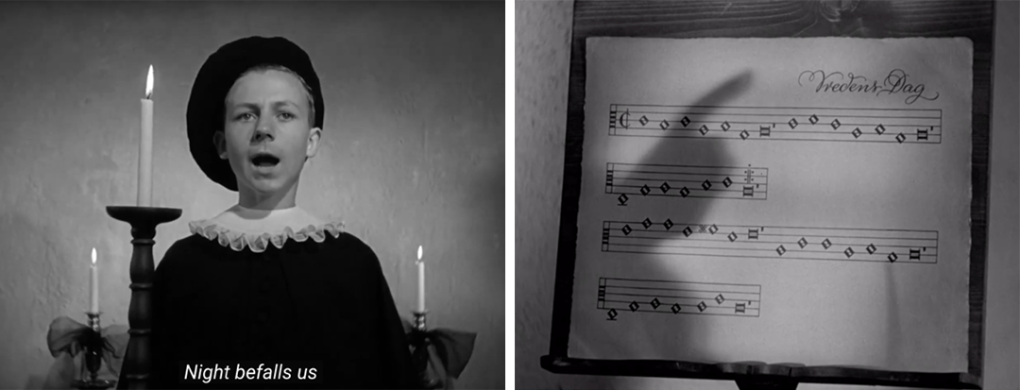

The most important musical theme is that accompanying the Dies Irae. The motif is immediately recognisable, sung in requiem services over centuries. Poul Schierbeck, the composer, utilises its meter and intervals, but replaces the usual unison with a two-part fugue, the theme therefore ‘chasing itself” and creating dissonance. The singing of the Dies Irae is also encoded visually into the film: first during rehearsal by a choir of ‘angelic’ young boys ahead of Herlofs Marte’s torture (Fig. 21, left); secondly, at her immolation (Fig. 21, right); third (Fig, 22, left), as the choir sings for the Absalon’s family and clergy around his bier.

Dreyer additionally deploys the visual impression of music to create a link to the film’s thematic extending beyond the purely sonic. First, the score is introduced into the film as another representational system. Like the Dies Irae scroll and the arrest warrant, it is authourless, thematically linked to the death warrant and inscription in the Church record of Herlofs Marte having been “burned, happily.” Milne (1977, 23) further notes that the score’s title (Fig. 22, right) is in the same script as used for writing the arrest and death warrants. Second, after the depiction of the choir rehearsal, the image of the sheet music is retained (Fig. 22, right), even as the sound of the choir fades out, replaced by Herlofs Marte’s shrieks. The choirmaster now effectively ‘conducts’ her torture – her shrieking is synchronised with his cues and tempo – thereby fixing this representation into the wider mechanism of social repression. Dreyer utilises this ‘conducting’ motif one more time, at Herlofs Marte’s immolation. Now, however, the motif is linked to the death thematic: after Herlofs Marte has been raised to maximum height on the ladder to which she has been bound (Fig. 23, left), Absalon ‘conducts’ a downbeat (Fig. 23, right) as signal to the executioners to push her into the flames. The two visual devices subtly yet poignantly associate the Church with torture and death.

Lastly, with regards to musical devices that support the diegesis, it is worth highlighting how ‘death’ sonically penetrates the nature scenes in a manner similar to the image of the horse-drawn cart carrying the wood for the pyre. While the music during the first, idyllic outdoor scene with Anne and Martin is lyrical (mostly solo violin), the theme is in fact a subtle variation of the Dies Irae motif.

Dreyer’s ‘effects’ in Day of Wrath’s underscore the gruesome nature of the plot, particularly with regards to the fate of Herlofs Marte. I argue that his principal intent with their deployment is to create a multi-dimensional representation of the Church as repressive force controlling the domestic as well as social sphere, and to broaden an (allegorical) reading of the film by elevating it out of its initial historicity. Whilst the Church is principally depicted as an anonymous, assembled force (Fig. 24, left), Dreyer is at pains to depict its members as ‘real’ and separate individuals (Fig. 24, right). The viewer is thereby forced to identify with them, increasing the impact of an allegorical reading. This is an advancement from Jeanne d’Arc, where the Church representatives are solely depicted in a grotesque manner, increasing the visual impact, but simultaneously distancing the spectator.

Conclusion

Day of Wrath is, as Dreyer (1970, Foreword) himself emphasised, his film most closely adhering to the principles of Aristotelian Tragedy in unity of time and space and the inevitability of outcome. The plot moves chronologically – its regular beat marked by the constant ticking of the clock in the rectory – and inexorably (a plot compressed from nine months in the original source material to only five days). Downplaying the source’s key thematic of witchcraft and pointedly refusing to take a position on whether Anne is a witch or not, Dreyer instead focuses the portrayal on a wider world whose inhabitants are both victims and perpetuators of an obdurate system of repression. This system is self-repeating, a perpetuum mobile, as evidenced by the Absalon-Martin, Herlofs Marte-Anne parallels, even in the cinematographic juxtaposition of the young choir boys and the elderly Clergymen. The film embodies a level of pessimism not witnessed elsewhere in Dreyer’s œuvre: “The latent tension, the smouldering horror…was what I tried to portray in Day of Wrath.” (1973, 34). In contrast to both preceding and succeeding films, no solution is proffered, beyond death. Joan in La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc may share Herlofs Marte and (likely) Anne’s fate, yet she achieves transcendence (Fig. 28, left) in her immolation, referenced in the film’s title. In contrast, Herlofs Marte neither hopes for nor expects a life beyond death, she is simply eradicated by the established order for refusing to be bound by its norms and rules. Ordet, which followed Day of Wrath, ends (Fig. 28, right) with Inge’s resurrection, her words “Yes, life, life, life” echoing her husband Mikkel’s “Now life is beginning for us” and the couple sharing a passionate kiss. Sacred and profane love succeed and are united, with Inge an “affirmation of life in itself” (Schrader 1989, 237). Day of Wrath, in contrast, ends with the defeat of love, when Martin rejects Anne to stand with the opposing force of Merete and the clergymen. The film’s final shot (Fig. 29) depicts the transformation of the Christian cross into the ‘death cross’ – first seen at Herlofs Marte’s immolation – standing not just as a repudiation of transcendence or resurrection, but also of the social structures within which society operates. Kau (1989, 255) argues this final image is “a condemnation of the whole world.”

What accounts for Day of Wrath’s unparalleled bleakness? Dreyer seemed even to be contradicting his inherent idealism and sense of purpose in filmmaking: he had previously stated (quoted Drum 1970, 211) that “I would not make films if I did not have the hope that in examining the motives which lead to the dramatic events in human history, the acts of violence, I was helping to spare future generations.” Personal difficulties over the previous decade and a World War that was at its bleakest when Dreyer wrote the script are obvious explanations for a plot and vision that border on the apocalyptic.

The choice of Church as institution on which the story hangs was predicated by the source chosen, but there is no evidence from Dreyer’s essays or previous films that there was any innate animosity on his part towards the Church; his essays and interviews display an ambivalence towards faith, and there is no direct criticism of the Church, either as State-supported institution in Denmark, nor elsewhere, beyond one reference to the Pope’s antisemitism (The Roots of Antisemitism, 1959). The short film, Landsbykirken (The Danish Village Church, 1947) that closely followed Day of Wrath presents the church’s functions in the life of a community in an entirely favourable light. When questioned on why he sought filmic expression through religious allegory, Dreyer (quoted Duperley 1968, 46) simply replied, “because I believe in tolerance. I am grieved by injustice.” Whilst there may therefore be an arbitrariness to the choice of institution through which he chose to display this injustice in Day of Wrath, it suited Dreyer’s purpose well, given its well-defined patriarchal structure, ingrained opposition to (female) sexuality, and hypocrisy. The implicit double irony in the film’s depiction of the oppression of the Church in the name of the Lord, and of its instigators also succumbing to the consequences of that oppression, was clearly of great interest to Dreyer, since this thematic is explored in much greater detail than in the source. Lastly, the Church’s stylised rituals and architecture would not only have resonated with the film’s audience but simultaneously offered Dreyer rich material with which he could meticulously create his own vision of great beauty. Sémoulé (1962, 114) argues that Day of Wrath was not only Dreyer’s most beautiful film, but that in creating it, he became Scandinavia’s greatest painter.

The choice of thematic allowed Dreyer to create two worlds: one, a meticulously reconstructed post-Reformation world, whose historicity supports a plot anchored in collective memory; the second, his personal and more abstract vision of images and meanings unencumbered by time. The film is an exemplar of what Michael Wood (1999, 218) describes as “not only an art of time but the art of his time, a modern, even a modernist art which cannot disentangle itself from the world it opposes.” The film is grounded in its time by its common narrative, deployed elsewhere in other contemporary Nordic films – Häxan (The Witches, 1922), Drama paa Slottet (‘Drama at the Castle’, 1943)– and in plays, such as The Devil in Boston and The Crucible. From a cultural perspective, Day of Wrath is also of its age in demonstrating the influence of literary trends prevailing at the time of its writing. Dreyer respected the Kammerspiel inspiration of his source material – key attributes are a small number of protagonists depicted within a concentrated time frame; focus on mise-en-scène; and limited set changes – onto which he grafted characteristics of Modernism, such as ambiguity in the portrayal of the protagonists, and an ending without closure. Both these literary trends were firmly anchored in Nordic culture. In a wider European perspective, Dreyer was, by the time of Day of Wrath, also likely influenced by Lukács’ call for socio-realism. This accounts for the relative lack of stylisation in Day of Wrath and clarity of presentation compared to Dreyer’s other films. Those films’ preoccupation with ‘essence’ was now replaced with a clear social messaging, if still far removed from didacticism.

Whilst functioning within its time-specific presentation, Day of Wrath resonates most powerfully as a portrayal of humanity ‘beyond time’: the historical – the seventeenth century setting – is lifted to the universal. As Carney (1989, 137) argues, “Dreyer’s hell is not as far off from our lives as Nazism. It is here and now and forever, and we too are potentially part of it, contributing to it, victimised by it.” This higher plane on which the film operates is largely achieved through Dreyer’s purification of the film’s aesthetics, which imparts on it a monumentality and sculptural quality only equalled by Gertrud. Alone within Dreyer’s œuvre, Day of Wrath combines beauty and purity with a purpose of social allegory: a critique of the institution(s) of repression, including of psychological and moral categories of understanding; and ultimately a critique of the limitations on self-representation, both in art and in life.

Notes

1. Unless otherwise stated, all translations from the Danish, Norwegian, German and French original are my own.

Bibliography

Bloch, E. (2020) “Discussing Expressionism.” Aesthetics and Politics. London: Verso.

Bordwell, D. (1981). The Films of Carl-Theodor Dreyer. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Carney, R. (1989). Speaking the Language of Desire: The Films of Carl Dreyer. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Doxtater, A. (2024). Art Melodrama in the Films of Carl Th. Dreyer. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

Dreyer, C.T. (1922). “Nye Idéer i Filmen.” Om Filmen. Gyldendals Ugebøger, Copenhagen.

Dreyer, C.T. (1964). “Script for Vredens Dag.” Copenhagen: Det Danske Filminstitut. Accessed 28th April 2024.

https://www.carlthdreyer.dk/carlthdreyer/filmene/vredens-dag.

Dreyer, C.T. (1970). Four Screenplays. London: Indiana University Press.

Dreyer, C.T. (1973). Dreyer in Double Reflection. Edited Skoller, D. New York: E.P. Dutton.

Drum, J. (2000). My Only Great Passion. The Life and Films of Carl Th. Dreyer. London: The Scarecrow Press.

Drouzy, M. (1982). Carl Th. Dreyer født Nilsson. Copenhagen: Gyldendal.

Duperley, D. (1968). “Carl Dreyer: Utter Bore? Or Total Genius?”. In: Films & Filming no. 5, vol. 14: 45-48.

Durgnat, R. (1966). Eros in the Cinema. London: Calder & Boyars.

Egholm, M. (2009). En visjonær fortolker af andres tanker: Om Carl Th. Dreyers brug af litterære forlæg. Copenhagen: Det humanistiske Fakultet, Københavns Universitet.

Feuchtwanger, L. (2021). Delusion, or The Devil in Boston. Boston: Independently Published.

Fletcher, A. (1965). Allegory: The Theory of a Symbolic Mode. Ithaca. Cornell University Press.

Kau, E. (1989). Dreyers Filmkunst. Copenhagen: Akademisk Forlag.

Kelman, K. (1965). “Dreyer.” In: Film Culture: An Anthology. Edited Sitney, P. London: Secker&Warburg.

Kracauer, S. (1960). Theory of Film: The Redemption of Physical Reality. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Lukács, G. “Realism in the Balance.” In: Aesthetics and Politics. London: Verso.

Manville, R. (1948). “Records of the Film.” British Film Institute. London.

Mathisen, O. (1988). Bogen om Poul Schierbeck. Copenhagen: Nyt Nordisk Forlag Arnold Busck.

Miller, A. (2015). The Crucible. London: Penguin Classics.

Milne. T. (1971). The Cinema of Carl Dreyer. London: Zwemmer.

Munk, K. (1953). Ordet. New York: The American Scandinavian Foundation.

Murrin, M. (1969). The Veil of Allegory. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Nash, M. (1977). Dreyer. London: BFI.

Neergaard, E. (1963). Bog om Dreyer. Copenhagen: Dansk Videnskabs Forlag.

Parrain, P. (1967). Dreyer: Cadres et Mouvements. Paris: Minard.

Sandberg, M. (2006). “Mastering the House: Performative Inhabitation in Carl Th. Dreyer’s The Parson’s Widow.” In: Northern Constellations: New Readings in Nordic Cinema, ed. C.Claire Thomson. Norwich: Norvik Press.

Schepelern, P. (2018). “Når ordet kommer til kort – Carl Th. Dreyer og musikken.” Accessed 3rd June 2024. https://www.carlthdreyer.dk/carlthdreyer/om-dreyer/filmisk-stil/naar-ordet-kommer-til-kort-carl-th-dreyer-og-musikken

Schrader, P. (1972). Transcendental Style in Film: Ozu, Bresson, Dreyer. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Sémoulé, J. (1962). Dreyer. Paris: Éditions Universitaires.

Söderberg, H. (1921). Gertrud. Skrifter, Femte Delen. Stockholm: Albert Bonniers Förlag.

Thomson, C. (2015). “The Slow Pulse of the Era: Carl Th. Dreyer’s Film Style.” In: Slow Cinema, ed. Tiago De Luca and Nuno Barradas Jorge. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP.

Trolle, B. (1955). “The Art of Carl Dreyer: An Analysis.” In: Kosmorama vol. 9.

Truffaut, F. (1980). The Films in my Life. London: Allen Lane.

Wiers-Jenssen, H. (1917). Anne Pedersdotter. Boston: Little, Brown & Company.

Wood. M. (2002). Cambridge Companion to Modernism. Edited Michael Levenson. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Filmography

Christensen, B. 1922. Häxan (The Witch). Skandias Filmbyrå.

Dreyer, C.T. 1919. Præsidenten (The President). Nordisk Films Kompagni.

Dreyer, C.T. 1921. Blade af Satans Bog (Leaves from Satan’s Book). Nordisk Films Kompagni.

Dreyer, C.T. 1921. Prästänkan (The Parson’s Widow). Svensk Filmindustri.

Dreyer, C.T. 1922. Det var Engang (Once Upon a Time). Sophus Madsen Film.

Dreyer, C.T. 1924. Michael. Decla-Bioskop.

Dreyer, C.T. 1926. Glomdalsbruden (The Bride of Glomdal). Victoria Film.

Dreyer, C.T. 1927. La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc. Société Générale de Films.

Dreyer, C.T. 1932. Vampyr (Vampire). Film-Production Carl Dreyer.

Dreyer, C.T. 1942. Mødrehjælpen (Good Mothers). Nordisk Films Kompagni for Mødrehjælens Fællesråd og Dansk Kulturfilm.

Dreyer, C-T. 1943. Vredens Dag (Day of Wrath). A/S Palladium.

Dreyer, C-T. 1947. Landsbykirken (The Danish Village Church). Dansk Kulturfilm

Dreyer, C-T. 1955. Ordet (The Word). A/S Palladium.

Dreyer, C-T, 1964. Gertrud. A/S Palladium.

Griffith, D.W. 1916. Intolerance. Triangle Film Corporation.

Ipsen, B. 1942. Drama paa Slottet (Drama at the Castle). Nordisk Films Kompagni.

Suggested citation

Peter Aurdal-Lawrence (2025), Aesthetics and Politics in Carl Th. Dreyer’s Day of Wrath. Kosmorama #289 (www.kosmorama.org).