"This film can be offered to foreign audiences without hesitation, saying: take a look, here is a piece of our fatherland, a glance to the life as it was lived in our countryside". - The film journal Filmiaitta’s anonymous reviewer on Anna-Liisa1.

Finnish silent cinema was looking for its national identity in the early 1920s. “The future of our cinema is the representation of our nature and national character,”2 actor Adolf Lindfors declared and in so doing expressed the sentiments of many Finns. After being an autonomous Grand Duchy of the Russian Empire since Sweden ceded it in 1809, Finland gained its independence in December 1917 in the aftermath of the October Revolution. Soon after becoming a sovereign state, the country plunged into a civil war of its own, which ended in May 1918. The events affected the ideologies behind filmmaking, as is evident already from the names of the newly founded companies.

The most long lived of these was Suomen Filmikuvaamo (Finland’s Film Manufacturer), which was established in 1919. Two years later it changed its name to Suomi-Filmi (Finland Film). National spirit was high in the country and it showed in film discussions and production. This was not the birth of Finnish cinema, however. Fiction films made in the country in the earlier decades have not survived to this day, but on the basis of the remaining fragments and contextual material, the lost heritage is better described as international than national (Salmi 2000). In the early 1920s, Suomi-Filmi attempted to model films after the Swedish films of the golden age that lasted from 1916 to 1924.

Sweden as the Forerunner of the Whole Film World

Casper Tybjerg argues that in neighbouring countries the masterpieces of Swedish cinema “were greeted with a mixture of admiration and envy, and many commentators in Denmark and Norway described them as examples well worth emulating” (Tybjerg 2016: 271). The same can be said of Finland. Svensk Filmindustri “has never put out inferior products,”3 Filmiaitta’s anonymous critic claimed in 1921. In comparison to the mass production of the Hollywood studios, this was a major difference. Finnish critics valued European films in general, but the Swedish films of the late 1910s and early 1920s were valued by many to the extent that Sweden was seen as “the forerunner of the whole film world.”4

In Finland, Swedish films of the golden age were especially highly regarded. There were two major reasons for this. First, most of the Hollywood feature films that were imported to the country were several years old (Seppälä 2012: 38–41). New first-rate films were simply too expensive or difficult to get. Finnish critics and audiences tended not to be aware of this matter. The new Hollywood films that were screened in the country were mostly cheap slapstick comedies and sensational melodramas, many of which were not made in the classical style. In comparison, Swedish prestige films like Ingmarssönerna (Sons of Ingmar, Sjöström, 1919) and Herr Arnes pengar (Sir Arne’s Treasure, 1919) were imported to Finland only months after their Swedish premieres. To exaggerate a bit, Finns ended up comparing the best Swedish films to the worst Hollywood films. Second, the national and ethnographic aspects of the imported Swedish films were experienced as reminiscent of Finnish culture. These aspects included everything from the representation of Nordic nature to that of local costumes and customs. “Swedish films are closest to the Finnish taste,”5 the pseudonym Barthel argued. In their familiarity to Finns, Swedish films differed in a positive way not only from Hollywood output but also from other European films.

Finnish audiences undoubtedly enjoyed American comedies and German crime films, but the audiences had a special relation to the golden age of Swedish cinema – especially with the works directed by Mauritz Stiller. It was at times even pointed out that Sången om den eldröda blomman (The Song of the Scarlet Flower, 1919) and Johan (1921) were actually Finnish films, even though they had been made in Sweden with Swedish money and talent. Both films are based on canonised Finnish novels written by Johannes Linnankoski and Juhani Aho, respectively. Stiller was discussed as a fellow countryman, as he had been born and raised in Finland and thus he knew the country well. As a Russian Jew, he moved to Sweden in order to escape military service in the tsar’s army. Johan also stars Urho Somersalmi who was a distinguished actor in the Finnish National Theatre. Indeed, it was easy for contemporaries to recognise that there is something very Finnish in these films.

In Finland, Swedish cinema was praised for being thoroughly national. Critics and reviewers argued that Swedish filmmakers adapted canonised literature and represented their own culture and common people6. Hollywood films, on the other hand, were regarded as international entertainment. The style of Swedish films gained its share of the admiration. To use modern terms, the Swedish films of the golden age were seen as minimalist. It was argued that they are artistically unobtrusive and avoid all kind of pretention and trickery, whereas Hollywood films were unnecessarily excessive and glamorous. Hollywood stardom and all kinds of ‘film tricks’ were heavily criticised by Finnish film journalists in the early 1920s (Seppälä 2012: 135–138). Swedish actors were something completely different; as they relied on modest devices, they were praised as mature artists7. Hollywood stars were seen as beautiful and fashionably dressed, but often as weaker talents in acting. Hollywood cinema was the bad object of Finnish cinema whereas Swedish cinema was the role model worth following (Seppälä 2012: 139–147). “Swedish cinema can function as a model for us. The things that are said in Sweden about our films, need to be used by us as the best lessons we can get for our future development,”8 an anonymous critic argued.

The Essentialist Finnish Cinema

To better understand this new Finnish national cinema, it can be called essentialist Finnish cinema, (Geertz 1973: 240–241) to apply the concepts of anthropologist Clifford Geertz. Finnish filmmakers working for Suomi-Filmi in particular wanted to create films that represent what many thought was the essence of the nation. One aim of these films was to create emotions of belonging among the audience and to intensify the feeling of togetherness in the newly established independent country that had been through a civil war (Seppälä 2012: 151). The essentialist Finnish films were often inspired by the domestic tradition of landscape painting, photography, literature and theatre. The new tendency was strongly evident in Kihlaus (The Betrothal, 1921), which was the first work in this new cycle of films. The now lost work was an adaptation of Finland’s national author Aleksis Kivi’s popular bucolic one-act comedy of the same name. The film was soon followed by Anna-Liisa (1922), Koskenlaskijan morsian (The Logroller’s Bride, 1923) and Nummisuutarit (The Village Shoemakers, 1923). As each was critically acclaimed and – on the basis of contemporary film journalism and advertisements – hugely popular among local audiences, they set a strong basis for the future of Finnish cinema.

Anna-Liisa, The Logroller’s Bride and The Village Shoemakers were made in the spirit of the Fennoman movement of the 19th century that had aimed at national awakening by stressing the importance of Finnish language and culture. The films are based on local literature written by Minna Canth, Väinö Kataja and Aleksis Kivi, respectively. While Canth and Kivi were canonised figures, Kataja is better described as a popular author who wrote about Finnish nature and folk culture. These essentialist Finnish films represent old traditions, customs and institutions, which, many thought, were now threatened by foreign tendencies such as the admiration of Hollywood stars and fashion. It is worth emphasising here that the concept of essentialist Finnish cinema does not imply that there actually was some national essence that was reflected in these works. The films merely exemplify, to borrow the words of Geertz, “the desire for coherence and continuity” (Geertz 1973: 244). The strength of the concept of essentialist lies in how it contrasts to Geertz’s definition of the epochal.

The Dialect of Essentialist and Epochal Impulses

Increasingly in the mid- and late 1920s, Finnish film companies produced works that reflect cosmopolitan tendencies. These epochal Finnish films are best understood as indications of the will of the filmmakers to represent modernity and related issues. Contrary to the essentialist films, they exemplify the desire for “dynamism and contemporaneity” (Geertz 1973: 244). In practice, this meant adapting certain international genre conventions and stylistic devices to Finnish cinema, often from Hollywood and Germany.

The category of the epochal Finnish cinema includes, for example, Kun isällä on hammassärky (When Father Has Toothache, 1923), Myrskyluodon kalastaja (The Fisherman of Storm Skerry, 1923) and Suvinen satu (Summery Fairytale, 1925). The first is an urban slapstick comedy, the second an adventure film and the third a high society comedy. Towards the end of the decade Finns filmed street films and spy films. These include Elämän maantiellä (On the Highway of Life, 1927) and Korkein voitto (The Supreme Victory, 1929). The epochal Finnish films, it seems, were not even nearly as popular as the essentialist films. When Father Has Toothache, The Fisherman of Storm Skerry, Summery Fairytale and other epochal films that were produced in the early and mid-1920s should not be seen as something radically new, as in the era of autonomy Finnish filmmaking had been largely epochal. Moreover, epochal impulses constantly mixed with essentialist ones.

The dialect of essentialist and epochal tendencies, which was vivid in Finland throughout the 1920s, exemplifies contradictions that were characteristic to the culture:

The tension between these two impulses – to move with the tide of the present and to hold to an inherited course – gives new state nationalism its peculiar air of being at once hell-bent toward modernity and morally outraged by its manifestations

(Geertz 1973: 243).

Adapting Minna Canth for the Screen to Attract the People

Teuvo Puro’s Anna-Liisa premiered on 20 March 1922. The film is based on proto-feminist author Minna Canth’s rural tragedy of the same name that she wrote in 1895. The play tells the story of a young woman who has killed her illegitimate child. Two men combat for the right to marry her, while she quietly struggles with her conscience and inner terror without anyone knowing about this. Finally, she confesses the infanticide in front of villagers who have gathered to celebrate her coming marriage. The play was an immediate success and it became the most popular of all of Canth’s works (Tanskanen 2010: 85–86).

Puro had filmed Anna-Liisa already in 1911 with Teppo Raikas and Frans Engström, but the film never premiered. Because there were no film laboratories in Finland at the time, the film stock was sent to Copenhagen for development. As the material was sent back to the filmmakers, it turned out that it was ruined – possibly because the cans had not been properly closed (Salmi 2000: 113). This nonetheless indicates that the impetus to exploit popular national literature and folk culture did not originate solely from the Swedish cinema, as it has at times been claimed. That same year Puro and his colleagues also made Sylvi, another film based on a Canth play, which premiered in 1913. According to Hannu Salmi, the filmmakers Puro, Raikas and Engström were heavily influenced by le Film d’Art productions and Danish art films such as Afgrunden (The Abyss, 1910) (Salmi 2000: 96, 108), which, like Anna-Liisa and Sylvi, is also a tale about a tormented woman.

The 1922 version of Anna-Liisa is a faithful adaptation of the play. Whereas professional theatre was considered a representative of high culture, films were seen in their entirety as a circus like representative of low culture (Pantti 1999: 123). The governmental film policy was only interested in censoring and tax collecting: there was absolutely no financial help being offered for filmmakers. Since 1921, films were categorised in two tax classes, which were science and art films (tax 20%) and other films (tax 30%). “Because film as art was not a self-conscious fact, but a cultural battle field, many attempted to define film as art by making use of the accepted art criteria that was influenced by Romantic art theory” (Pantti 1999: 54). Filmmakers consciously adapted elements from canonised arts to their films. A similar strategy had been used in French Le Film d’Arts and German Autorenfilms. Considering that Swedish films were highly praised for their artistic quality, this further explains why Finnish filmmakers began to follow this model and turned increasingly towards canonised Finnish arts. As a result, it was possible to argue that Finnish cinema was educating entertainment like theatre (Seppälä 2012: 55, 139, 151, 371).

But if Finnish film production was to bloom, films needed to reach large audiences. That was more easily said than done, as the events of 1918 had divided the nation in two. On the field of theatre, political alignments had split the audience to the supporters of the workers’ theatre or bourgeois theatre (Seppälä 2010: 118–160). Thus, the concept of the national audience was time and again brought up in public film discussions. Adapting canonised works for the screen was a way to avoid discussing – or even referring to – the pressing social issues of the day. In this Canth’s plays were obvious choices, as they were not only highly regarded by critics, but also popular among audiences of both professional and amateur theatres. Theatres, on the contrary, were able to perform even civil war plays. The cinematic look backward to the pre-war tranquillity was a strategy to attract audiences from the winning and losing sides. But even this was not enough to make Finnish film production economically profitable. According to Outi Hupaniittu, “during the silent era, the international film business was the backbone of the operations in Finland,” (Hupaniittu 2016: 46) as “it was not possible to make productions truly profitable” (Ibid.: 42).

Anna-Liisa and the Swedish Peasant Film as a Model of Possibilities

The influence of the Swedish peasant film, a category into which many of the films of the golden age can be placed, is evident in the essentialist Finnish films of the 1920s, especially in their mise-en-scène. This is not to say that the peasant film was the sole influence (Seppälä 2016). The Swedish masterpieces strengthened the faith of Finnish filmmakers in the exploitation of their own nature, customs, costumes and items, and – most importantly – showed how these could be narratively motivated (Seppälä 2016: 74). By using Anna-Liisa as a case study, I will now indicate how the Swedish cinema influenced it and – in relation to this – what meanings does the film make available. I will concentrate on Anna-Liisa’s representation of nature, exploitation of folk culture and use of Canth’s language.

Landscapes, Nature and Human Psychology

Nature and landscapes have a special place in all five Nordic cultures, which among other things shows in the arts of the region. “Landscape is the genre of Nordic painting” (Alsen and Landmann 2016: 136). When it comes to filmmaking, Antti Alanen claims that “[t]he Finns could not compete with the Americans or the Germans in budgets, but nature itself was sublime, incomparable and majestic” (Alanen 1999: 80). Natural landscapes had been seen in Finnish fiction films already in the pre-independence period. In actualities, they were numerous and prominent. “Finland did not have grand history or much of anything else to be admired, but [authors Johan Ludvig] Runeberg and [Zachris] Topelius had raised landscape – especially lakes, for example images from Koli – as a special national treasure” (Honka-Hallila 1995: 49) that artists could utilize.

Even though Swedish filmmakers did not provide the sole impetus to exploit landscapes and nature, their work was influential in that it showed how these could be narratively motivated and function as expressions of inner emotions of characters. Victor Sjöström, for example, was praised for the way in which he uses images of a storm to imply the rage of his titular character in Terje Vigen (A Man There Was, 1917). Stiller, on the other hand, famously uses the river as sign of the untamed sexuality of his protagonist in The Song of the Scarlet Flower. Both filmmakers were undoubtedly influenced by Nordic landscape paintings in which nature was being “perceived as an extension of the subject and as an element of connection to that subject’s innermost self” (Alsen and Landmann 2016: 136).

Being a notable critical and popular success in Finland, The Song of the Scarlet Flower influenced Puro and his screenwriter Jussi Snellman to the extent that they added a sequence of logrolling to Anna-Liisa. This is noteworthy, as there are no logrolling scenes in Canth’s play, perhaps due to the fact that they must have been challenging for a theatre stage, even though one the characters is a lumberjack – the whole play takes place indoors. In the 1920s, Finnish critics emphasised how important it was for filmmakers to remain faithful to the nature of the literary works they adapt9, while they were at the same time requested to broaden the diegetic world of the stories10. By adding the logrolling sequence Puro and Snellman achieved just this.

Mikko, who has made Anna-Liisa pregnant, is one of the two men who combat for the right to marry her. The film introduces him standing on floating logs close to the shore with a pike pole in his hand. Behind him, the river runs as a symbol of his wild sexuality.

He soon sits down and in a lengthy flashback remembers how he fell in love with the titular character and had illegitimate sex with her. In the flashback, Mikko meets Anna-Liisa carrying a baby lamb, a well-known sign of innocence, which she gives to him.

The implication of the contrasted symbols is that Anna-Liisa is sexually inexperienced and naïve, which makes her an easy prey for Mikko’s predatory sexuality. The Stiller film contains similar symbolism, as “the scarlet flower” in the title implies.

In another flashback, self-destructive Anna-Liisa tries to commit a suicide. The film shows her from an extreme high angle in an extreme long shot, as she walks to the edge of a shore cliff.

While the rock is static, way down below the water is clearly flowing to the left. The cliff stands for life and the stream for death that could easily carry her away. Instead of jumping, Anna-Liisa falls on her knees and prays. As she does so, the camera shows the lower half of her body against the rock and the upper part against the stream.

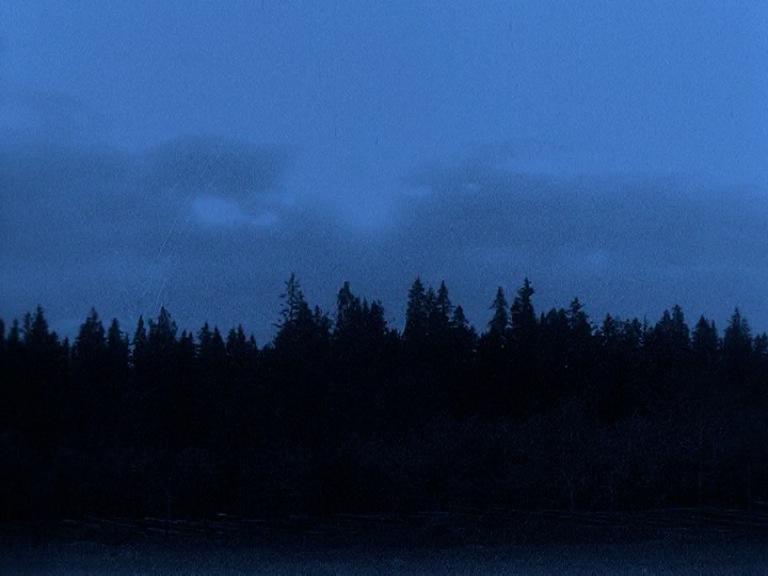

The composition emphasises the impossible situation she is in, as her dual desire to live and die is tearing her apart. In one sequence the film shows the protagonist soon after she has murdered her illegitimate child. Here Puro uses extreme long shots of a forest horizon.

A storm rages, and long shots and full shots of Anna-Liisa amongst small trees and bushes shivering in the heavy wind.

They give an added emphasis to the state of terror and hopelessness she is in.

These examples indicate that the film narratively motivates nature, as Sjöström had done in A Man There Was and Stiller in The Song of the Scarlet Flower. The same strategy is used in many essentialist Finnish films, as it was a salient solution in tying people and nature closely together, making them effectively inseparable. Precisely in this sense the depiction of natural landscape was used in Finland as a highly significant index of the national identity, even though the convention was adapted from the Swedish cinema.

Ethnographic Issues from Costumes to Customs

Finnish critics placed a great emphasis on the importance of depicting local cultures in a faithful way. Ethnographical accuracy became a major characteristic of the essentialist Finnish cinema. It is worth keeping in mind that the best Swedish films were praised for their authentic representation of Swedish folk culture and common people. In the early 1920s, some Finnish critics and representatives of film business worried that if Finns do not start making adaptations of their national literature, others will make them for them (Hupaniittu 2016: 32). The Song of the Scarlet Flower and Johanwere regarded as great films, but some foreign representations of Finnish culture were viewed as nothing less than disgraceful. Carl Th. Dreyer’s Blade af Satans Bog (Leaves from Satan’s Book, 1921) is a case in point. Oski Talvio heavily chastised the last episode of the film, which is set in Finland of the Civil War months:

I really cannot say whether I was supposed to cry or laugh when I was watching the last episode of this film, because the depiction of our country, of its great Civil War, of our people, of our religion and manners was as false and unjust as possible. […] Just to mention a few examples about this. Siri’s cottage was made of round unshaped timber, which made it look both from outside and inside just like a Russian cottage […] and what is even more: Siri, before going to bed, goes to the image of God, which hangs in the corner, and makes the sign of cross in a fully Russian manner!11

Talvio was seemingly annoyed by the way his country and its culture were represented in an unauthentic manner in the Dreyer film. By the Russian manner, he meant that Siri crosses herself; she crosses herself from right to left, as the Orthodox do, rather than left to right as Protestants do. Even the character in question had been named incorrectly, as the Finnish version of Swedish Siri (that is a variant of Sigrid) is Siiri. What Talvio saw as so important were the ethnographic aspects of the film, which he found to be wrongly represented. Those little details have little to do with the drama of the film, as Dreyer answered in his feedback criticism12. But for Finnish critics of the time, just as a film needed to be faithful to the original artwork, it needed to be faithful to the ethnography of the nation it represented. In this, the Swedish filmmakers were forerunners. The Civil War episode was not publicly shown in Finland, as film censors cut it out.

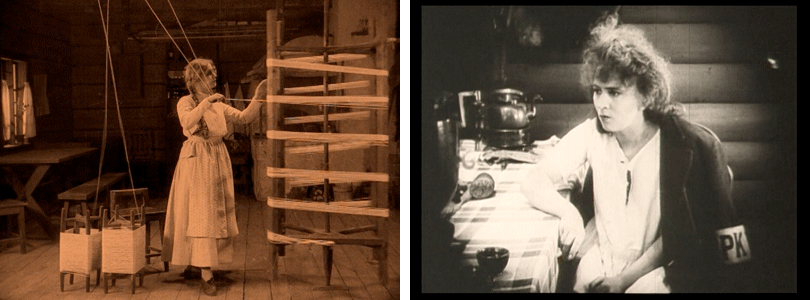

In the opening sequence of Anna-Liisa, the titular character is working in a room in her parents’ house. She stands in the foreground of the shot working on a warping reel. Her hair is on a long thick plait and she wears a white skirt and a high collared blouse on top of it. The clothes that fully cover Anna-Liisa’s body are protected by an apron that is modestly decorated with small spots. Her feet are covered by white socks and leather shoes. Contrary to Dreyer’s Siri, Anna-Liisa can be instantly recognised as Finnish.

The quality of her clothes indicates that she is the daughter of a farm-owning family. They also suggest that she is a caring, discreet and God-fearing.

As Anna-Liisa works with the warping reel, the film implies that she is in control: the machine turns around in the rhythm of her hands and the strings spring around it. The audience soon learns that she is going to make fabric for her own wedding dress, according to Finnish custom. In the 19th century, women’s manual skills were especially important, as they were responsible for making clothes for the entire family. By making her wedding dress, the future bride demonstrated to the female members of her new family that she was manually skilled. In addition, the dress was an indication of the wealth and status of the family. Anna-Liisa soon stops and sits down with a worried expression on her face. While everything is well on the outside, it is obvious that she has pain in her heart.

The house Anna-Liisa lives in is built of planed timber, unlike the ‘Finnish’ cottage in Leaves from Satan’s Book. At the time the film was made, the production company Suomi-Filmi was making sets not only for its films but first and foremost to theatre companies (Hupaniittu 2016: 33). On the left of the shot the audience can see a long table and bench while the background wall is covered by a full cupboard and towels. The décor, which was created by the set designer Carl Fager, is reminiscent of canonised Finnish paintings of the 19th century that depict interiors of rural houses, a good example of which is Adolf von Becker’s Sunnuntaiaamu pohjalaistuvassa (Sunday Morning in an Ostrobothnian House, 1870s). The Swedish filmmakers had also found inspiration from paintings and drawings. Stiller famously paraphrased Albert Edelfeldt’s illustrations for Lagerlöf’s Herr Arnes penningar in his adaptation of Sir Arne’s Treasure. In his article on the Swedish films Tybjerg argues that “at least as important as getting period and local details right was matching iconography that had already been established by genre painters and illustrators” (Tybjerg 2016: 276). The same tendency is evident in the essentialist Finnish cinema.

Artistic Quality and Intertitles

When it comes to cinematography, editing and mise-en-scène, the style of the essentialist Finnish films can be productively analysed in terms of “cinematic theatricality” (Seppälä 2016: 57–78). But in their heavy use of intertitles, the films are self-consciously literary. The status of Anna-Liisa as an adaptation was not hidden or played down, but brought explicitly to light in the intertitles: the film includes several direct quotations from Canth’s play. This way Anna-Liisa could include bits and pieces of the original art work for the audiences to recognize and enjoy. An important function of the quotations was to increase the cultural prestige of the film. While direct quotations added cultural prestige, in terms of filmmaking they were problematic. Many of Canth’s lines were simply too long to be effective in intertitles whereas others conveyed only little information when taken out of their original context. Therefore, more often than not, the adapted lines had to be altered to suit the narration of the film better – many of the lines were shortened while others were collected from several lines of dialogue.

Johannes, who is deeply in love with Anna-Liisa, comes to meet her, as she is using the warping reel. The first line of dialogue is a direct quotation from the play: “Are you still going to start making fabric?” In some of the masterpieces of the golden age of Swedish cinema, the first sentence of the adapted novel corresponds with the first intertitle of the film (Hanssen and Rossholm 2012: 156). The line, however, is not the first line of the play. “Good day, Anna Liisa” (Canth 2001: 11), which is the first line, conveys so little information, that the filmmakers decided not to use it. Furthermore, the first half of the used line was cut out, as the filmmakers wanted to go straight to the point. In the film, Johannes soon says to her: “I have something very important in mind.” This short intertitle is actually collected from two long lines that are parts of a conversation in the play:

Johannes: You do not say? A wedding dress! But in that case, you have to hurry. Do you know what I have in mind now?

Anna Liisa: Well? Tell me.

Johannes: Oh no – ! Not while you are working, as it is something so very important. Please sit down by the table and I will tell you. (Canth 2001: 11–12)

The used line further indicates that the filmmakers respected Canth’s language, while they wanted to achieve fluid cinematic narration. As Johannes tells Anna-Liisa that he wishes that a priest will publicly announce that they will be married in three weeks, she is terrified; she worries that her crime will be revealed. In Canth’s play, Anna-Liisa says: “Before we go to the vicarage, I still have to ask you Johannes: are you sure that you will never regret this?” (Canth 2001: 13) In the film, she only says: “But are you sure that you will never regret this?” This is an example of a line that is both shortened and slightly altered to make it work in the intertitle. In the film, Johannes tells her that there is no-one like her, as she is above everyone else. To this Anna-Liisa replies: “Do not speak like that, I am not better than others, I am worse.” In the play the line is significantly longer: “No, that is not true. I am not better than others, I am worse. This is precisely what worries me, that you think so much good of me.” (Canth 2001: 15) The use of such lines in intertitles would have made the narration drag.

The convention of including some of the dialogue of the play in the intertitles was probably adapted from the admired Swedish films. As Eirik Frisvold Hanssen and Sofia Rossholm argue, the “use of direct quotations implies a notion of ‘double authorship’ underlining […author’s] authorial presence” (Rossholm and Hanssen 2012: 150). According to Bo Florin, even though Sjöström abridges, compresses and rearranges individual scenes of A Man There Was, the intertitles are largely true to the wording of Henrik Ibsen’s poem on which the film is based. In Stiller’s Sir Arne’s Treasure, each intertitle is taken word for word from Lagerlöf’s novel (Furhammar 2010: 89).

Swedish filmmakers had turned to canonised literary works in their attempt to make film a more respectable art form, as “artistic quality was seen synonymous with literary quality” (Ibid.: 87). Now Finnish filmmakers did the same. Puro had directed two Canth adaptations already in 1911, but now adaptations of Finnish literature were becoming common. Whereas Swedish filmmakers adapted Nordic literature, their Finnish colleagues relied solely on local fiction. Finland was a newly sovereign nation and artists wanted to enhance and celebrate its national identity. In this sense, Finnish cinema was more national than its Swedish counterpart.

Conclusions

In Finland, Swedish films of the golden age were held in high esteem. Not only were they seen as being close to the Finnish taste, but also miles ahead the old Hollywood films that were being imported to the country in the early 1920s. As my analysis of Anna-Liisa indicates, the essentialist Finnish cinema was an inherently transnational enterprise, as it was modelled after the Swedish example. The films of the golden age were influential as models of possibilities in their use of intertitles and representations of folk culture and nature. The function of the adapted elements was to enhance the cultural prestige of Finnish films and raise them to the level of the Swedish cinema. Other cinemas were certainly influential as well, but not as much as the Swedish one.

After Anna-Liisa had had its premiere in Sweden, it was proudly reported in Finland that Swedish critics had noticed the family resemblance and compared Anna-Liisa to Sons of Ingmar and Tösen fron stormyrtorpet (Girl from Stormy Croft, 1917)13. Finns were also told that most Swedish critics had praised Anna-Liisa’s representations of Finnish nature and folk culture. This was nothing less than a cause for celebration. The film received negative criticism as well, but as this came from the country that was regarded to be the forerunner of the whole film world, it was humbly taken. However, using the Swedish cinema as a role model and borrowing its conventions was not enough to raise the essentialist Finnish cinema to international consciousness. In a few years, even the reputation of the Swedish cinema began to fade, as it turned increasingly towards cosmopolitan topics. Apart from a few exports, the essentialist Finnish cinema was to remain a local attraction, no matter how closely it was connected to the Swedish masterpieces.

BY: JAAKKO SEPPÄLÄ / CHAIR FOR FINNISH SOCIETY FOR CINEMA STUDIES/ TEACHES AT THE SCHOOL OF FILM AND TELEVISION STUDIES, UNIVERSITY OF HELSINKI

The author thanks Tiuku Talvela for her help in the analysis of 19th century Finnish folk culture.

Jaakko Seppälä is the chair for Finnish Society for Cinema Studies and a part-time teacher at the School of Film and Television Studies, University of Helsinki.

Notes

1. “Filmitulkinta Minna Canthin ’Anna-Liisasta’”. Filmiaitta 6/1922, 98.

2. “Mitä kotimaiset filmitähtemme kertovat”. Filmiaitta 13/1923, 169.

3. “Kolme ruotsalaisen filmitaiteen mestariteosta”. Filmiaitta 8/1921, 115.

4. “Miten ’Koskenlaskijan morsianta’ arvostellaan Ruotsissa”. Filmiaitta 7/1923, 79.

5. Barthel: “Svanstan kreivit”. Filmiaitta 1/1925, 10.

6. “Hiidenluolan kuningas”. Filmiaitta 15/1925, 197.

7. Edward Welle-Strand: “Pohjoismainen filmikulttuuri”. Filmiaitta 13/1922, 204.

8. “Miten ’Koskenlaskijan morsianta’ arvostellaan Ruotsissa”. Filmiaitta 7/1923, 79.

9. “Murtovarkaus” Filmiaitta 12/1926, 199.

10. “Puhenäytelmä filminä”. Filmiaitta 1/1925, 6.

11. Talvio, Oski: ‘Sananen tanskalaisesta filmistä, jolla on aiheena meidän vapaustaistelumme’. Filmiaitta 2/1922, 35.

12. ”Lehtiä paholaisen kirjasta” filmin johdosta’ Filmiaitta 5/1922, 92.

13. ”Suomen Filmitaiteen vastaanotto Ruotsissa”. Filmiaitta 18/1922, 282.

References to periodicals

Filmiaitta 1921

Filmiaitta 1922

Filmiaitta 1923

Filmiaitta 1925

Filmiaitta 1926

Bibliography

Alanen, Antti (1999). “Born Under the Sign of the Scarlet Flower: Pantheism in Finnish Cinema”. In: Fullerton, John and Olsson, Jan (ed.) Nordic Explorations. Film Before 1930. London et al., John Libbey.

Alsen, Katharina and Landmann, Annika (2016). Nordic Painting. The Rise of Modernity. Munich et al., Prestel.

Canth, Minna (2001/1895). Anna Liisa. Helsinki, WSOY.

Clifford, Geertz (1973). The Interpretation of Cultures. New York, Basic Books.

Furhammar, Leif (2010). “Selma Lagerlöf and Literary Adaptations”. In: Larson, Mariah and Marklund, Anders (ed.) Swedish Film. An Introduction and Reader. Lund, Nordic Academic Press.

Hanssen, Eirik Frisvold and Rossholm, Anna Sofia (2012). “The Paradoxes of Textual Fidelity: Translation and Intertitles in Victor Sjöström’s Silent Film Adaptation of Henrik Ibsen’s Terje Vigen.” In: Raw, Laurence 2012 (ed.) Translation, Adaptation and Transformation. London and New York, Continuum International.

Honka-Hallila, Ari (1995). ”Elokuvakulttuuria luomassa”. In: Honka-Hallila, Ari, Laine, Kimmo and Pantti, Mervi (ed.) Markan tähden. Yli sata vuotta suomalaista elokuvahistoriaa. Turku, Turun yliopiston täydennyskoulutuskeskus.

Hupaniittu, Outi (2016). “The Emergence of Finnish Film Production and Its Linkages to Cinema Businesses During the Silent Era”. In: Bacon, Henry (ed.) Finnish Cinema. A Transnational Enterprise. London, Palgrave MacMillan.

Pantti, Mervi (1999). “Kansallinen elokuva pelastettava”. Elokuvapoliittinen keskustelu kotimaisen elokuvan tukemisesta itsenäisyyden ajalla. Helsinki, Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura.

Salmi, Hannu (2000). Kadonnut perintö. Näytelmäelokuvan synty Suomessa 1907–1916. Helsinki, Suomen elokuva-arkisto and Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura.

Seppälä, Jaakko (2012). Hollywood tulee Suomeen. Yhdysvaltalaisten elokuvien maahantuonti ja vastaanotto kaksikymmentäluvun Suomessa. Helsinki, Unigrafia.

Seppälä, Jaakko (2016). ”Finnish Film Style in the Silent Era”. In: Bacon, Henry (ed.) Finnish Cinema. A Transnational Enterprise. London, Palgrave MacMillan.

Seppälä, Mikko-Olavi (2010). Suomalaisen työväenteatterin varhaisvaiheet. Helsinki, Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura.

Tanskanen, Katri (2010). ”Idealismista illuusioon”. In: Seppälä, Mikko-Olavi and Tanskanen. Katri (ed.) Suomen teatteri ja draama. Helsinki, Like Kustannus.

Tybjerg, Casper (2016). “Searching for Art’s Promised Land: Nordic Silent Cinema and the Swedish Example”. In: Hjort, Mette and Lindqvist, Ursula (ed.) A Companion to Nordic Cinema. Chichester, Wiley Blackwell.

Suggested citation

Seppälä, Jaakko (2017): Following the Swedish Model: The Transnational Nature of Finnish National Cinema in the Early 1920s. Kosmorama #269 (www.kosmorama.org).