Thora van Deken (it was given the English-language title A Mother’s Fight by the production company, but I will be using the original title here) has not found a place among the canonical works of the Swedish “golden age” (for a thorough discussion of the concept and its history, see Florin 1997, particularly chapter 1). “Snowy wastes and simple hearts” is how the influential 1930s film historians Maurice Bardèche and Robert Brasillach somewhat facetiously summed up the Swedish cinema of this period (Bardèche and Brasillach 1938, 187)1, and this characterization has long persisted. In Thora van Deken, however, there are no characteristically Nordic, snow-covered landscapes, nor are its characters unassuming rustic types; the film lacks the folkloristic ambience which many contemporaries regarded as a key quality of films like Victor Sjöström’s The Sons of Ingmar. Nevertheless, Thora van Deken was explicitly presented and received as part of the same school or trend on the basis of its psychological realism and of the literary prestige of its source.

The short novel on which Thora van Deken was based bore the subtitle “A Portrait”. The film, too, is a portrait of a woman, a stern and unbending one. In a promotional pamphlet for the film, it is described as “… the first Swedish film production with a modern setting where the essential is the portrayal of inner life” (Skandiafilm 1920). “The portrayal of inner life” is my translation of “det själsliga innehållet” – innehåll means content, and själslig means pertaining to the soul or mind. The promotional material for Thora van Deken, in other words, emphasizes that its drama is psychological. In the words of its director, John W. Brunius, “it was not based on external effect, but the artistic rendering of psychological light and shade” (AB Svenska Biografteatern 1920, 3). Watch the film on Filmarkivet.se.

In 1920, Carl Th. Dreyer (then an up-and-coming young director) had written that the distinctive quality of the Swedish cinema of the post-Terje Vigenperiod – in contrast to both action-packed American movies and the crime thrillers and melodramas dominating the output of the Danish film industry – was its emphasis on psychology rather than physical action: “The Swedish art film […] has acquired its distinctive character by becoming a medium for true and genuine human representation” (Dreyer 1973, 28). On this view – which was echoed by a number of commentators at the time – Thora van Deken was very much a film that shared this distinctive character.

I have argued for this more expansive conception elsewhere (see Tybjerg 2016), and this issue of Kosmorama is intended to support it. What I wish to do in the present article is to examine both Thora van Deken’s literary roots and the way it gives us access to the mind and emotions of its main character, showing how the film fits into the Swedish quality film model of the late teens and early twenties.

The first section of the article examines the film as an adaptation. Because of the complexity of the source material and also because of Pontoppidan’s stature as one of the greatest of all Danish novelists, I have thought it worthwhile to go into considerable detail here. The second section compares the finished film to the two different versions of the screenplay that survive, showing that even though director John Brunius had previously directed a dramatization of the novel, the film sought a more novelistic effect through the extensive use of brief flashbacks; the gradual shifts, over the course of screenwriting process, in the way these flashbacks were used was vital to one of the most fascinating aspects of Thora van Deken: the way it consistently aligns us with the title character and her point of view.

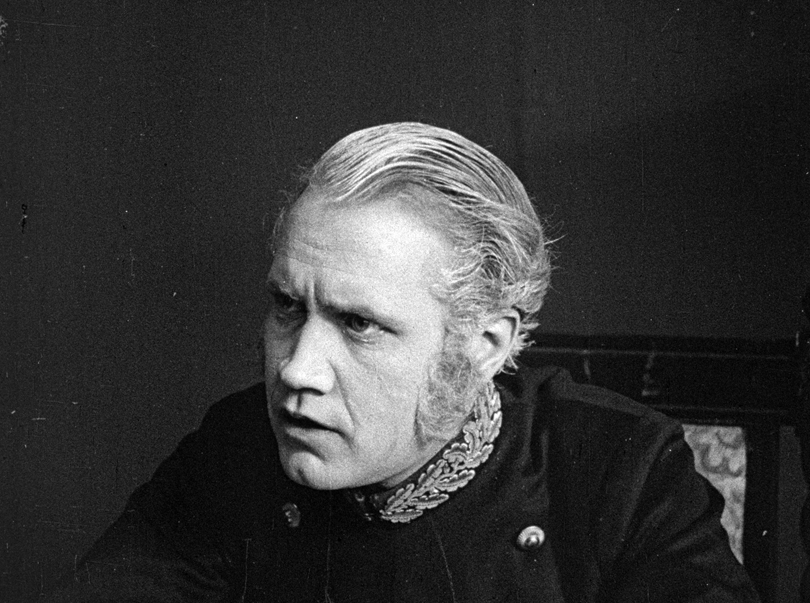

The third section will examine the way this is achieved in individual scenes through point-of-view structures. This will necessitate some theoretical discussion of the notion of point of view, because some of the most influential accounts of it are in my view profoundly misleading: they tend to privilege point-of-view shots as vehicles of character subjectivity. The work of literary theorist Alan Palmer provides a useful perspective on the source of this mistaken emphasis. Murray Smith’s classic book Engaging Characters (1995) theorizes the concept of point-of-view structures, and I shall draw on his and Torben Gordal’s work, as well as Palmer’s ideas, to support my argument that in most dramatic films, character subjectivity is largely presented through the actors and their performances. In the case of Thora van Deken, point-of-view shots and flashbacks do contribute to aligning us with the title character, but the main means of presenting Thora’s inner life to spectators is showing her reactions in long and searching close shots.

I develop these ideas further in the remaining two sections. The fourth section is devoted to the extended analysis of a key sequence from the film, showing how framing, editing, and (most importantly) performance interact to present the main character’s subjective states. The fifth and last section looks at the use of close shots, a key component of the film’s aesthetic strategy, discussing them in relation to contemporary debates. I shall conclude that the careful artistic choices of Brunius and his collaborators made Thora van Deken a first-rate psychological drama that also reveals that the Swedish quality cinema around 1920 was a bit more diverse than some film historians have suggested.

Novel(s), Play, Film: A Complex Adaptation

Thora van Deken was an adaptation of a short novel by the Danish novelist Henrik Pontoppidan, who won the Nobel prize in literature in 1917 together with his compatriot Karl Gjellerup, making it the second of a series of adaptations by director John Brunius and screenwriter Sam Ask of works written by Nordic Nobel prize winners. Brunius, a successful actor and stage director, was the artistic head of the film company Skandia; the company rose to prominence in 1918-19 following a policy of making literary films from works by leading Nordic writers and with established stage actors in the leading roles, a policy emulating the older company Svenska Biografteatern. The latter had a close association with Selma Lagerlöf, who won the prize in 1909, but Brunius seems to have followed a plan of adapting all the other Nordic Nobel laureates. The first was Synnöve Solbakken, an adaptation of a novella by Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson, the 1903 laureate, shot in the summer of 1919. Later that summer, he shot Thora van Deken, which premiered in March 1920. When Skandia merged with Svenska Biografteatern to form Svensk Filmindustri at the end of 1919, Brunius was able to continue with adaptations of both the Dane Karl Gjellerup (Kvarnen, 1922) and the Norwegian Knut Hamsun, who won in 1920 (Hårda Viljar, 1922).

Before going in to the complexities of Brunius’ and Ask’s adaptation, I think it is most useful to briefly outline the film’s plot: Thora van Deken is the story of the divorced wife of Squire

Engelstoft, a wealthy landowner. Her life has been marked by a fear of poverty since her wastrel father (van Deken is her maiden name) threw away the family fortune and left his children in destitution. Determined to protect her daughter’s future, Thora steals her ex-husband’s last will to ensure that their daughter will inherit his splendid manor house (which he had willed to a charitable foundation). After the husband’s death, she takes over the manor; suspicions of foul play force her to perjure herself to conceal the theft of the will. Esther, the daughter, cares little for the inheritance, however; she falls in love with a handsome young minister and wishes to devote herself to helping him in his calling, finally eloping with him when he goes off to inner Asia as a missionary. All Thora’s efforts having come to nothing, she admits to her theft and her perjury, and she is taken away.

Thora van Deken was not the story’s original title. Henrik Pontoppidan first published the novel Lille Rødhætte: Et Portræt (“Little Red Riding Hood: A Portrait”) in 1900. An inveterate reviser, Pontoppidan published a rewritten version in 1909, changing nearly every sentence as well as some major plot points. The novel was adapted for the stage by playwright Hjalmar Bergstrøm with considerable assistance from Pontoppidan. The play opened in 1914 in Copenhagen, and a Swedish staging followed later that year, directed by Brunius (with several members of the cast – Hugo Björne as the husband, Gösta Ekman as the minister – reprising their roles in the film version). For the play, the title was changed to Thora van Deken.

The novel’s original title springs from the recollections of the local investigating magistrate who has been in love with Thora since they were both children: back then, she wore a red hood, giving her the nickname Little Red Riding Hood. This minor subplot was dropped in the dramatization, probably motivating the title change (although the German translation of the novel from 1910 was also called Thora van Deken, and Pontoppidan himself adopted the title for his second 1922 revision of the novel). “Little Red Riding Hood” also suggests the original innocence of Thora, a babe in the woods, whom the dishonesty and rapaciousness of men has turned into a wolf, convinced that the world is a place where the strong prey ceaselessly on the weak, where cruelty is the price of survival. This is made explicit in an intertitle in the second of the two versions of the screenplay. At the end, Thora having confessed her crimes to the magistrate, he offers her a chance to escape (he is still in love with her). But she replies:

What good would that do? Men are everywhere the same. I now only wish to be completely alone. That might perhaps help me forget. Once, I was an unsuspecting little girl who imagined that life was like a nice old granny. They called me little red riding hood, after all. (Script II, p. 86).

The screenplays add further title variants: the first is entitled “En vargmoder” [“A Mother-Wolf”] with “(Thora van Deken)” in parenthesis, the second “Fru Thora” [“Mrs. Thora”]; hand-written stickers on the bound covers instead bear the titles “Fru Thora I” and “Thora II”. In what follows, I will refer to them as “Script I” and “Script II”.

The most obvious differences between the various versions concern the ending. In the original version of the novel, the daughter reveals to the minister that her mother has stolen the will, and the minister in turns informs the magistrate, who then confronts and arrests Thora as the daughter and the minister depart for distant shores. In the 1909 and 1922 versions, Pontoppidan has the daughter fall ill and die rather than elope with the minister. This change means that certain scenes in the novel which in the 1900 version were dramatically motivated (because they provided clues that for the magistrate that would later corroborate the minister’s information about Thora’s guilt) seem less purposeful in the later versions, particularly a scene with a night-watchman observing Thora visiting her study in the dead of night.

Both stage-play and film stuck with having the daughter run away rather than die. In the last act of the play, the minister proposes to Esther, and she accepts. Thora forbids the marriage when she realizes that the minister and Esther intend to give away her inheritance to the poor. In a desperate attempt to convince Esther that she has her interests at heart, Thora reveals her crime to her horrified daughter and demands that she choose either to remain or see her mother in jail. The magistrate arrives on other business; while he is talking to Thora, she receives a note from her daughter notifying her that she has already left. Thora then takes out the will and admits her crime.

The film’s ending is similar, but Thora never reveals directly to the daughter what she has done. In the film’s version of the scene where Thora demands that the daughter choose, the minister is still in the room, allowing the daughter’s choice to be made manifest in the staging of the shot. Thora sits on the left side of the frame and the minister stands on the right, meaning that the daughter literally takes sides when she steps forward into the room: she moves to the right side of the frame to stand beside the minister.

The significance-laden arrangement of this shot may seem theatrical, but the scene is actually specific to the film. As David Bordwell has shown, the cinema ensures that such blocking effects are seen in the same way by every viewer – from the vantage point of the camera – allowing them to be much more precise than would be possible on the stage (Bordwell 1997, 182-198).

One might think that the film version was largely based on the dramatization, particularly since Brunius had directed Bergstrøm's dramatization on the Stockholm stage. The screenplays, however, include a number of elements that go back to the source novel, including an introductory scene at a train station (with expositional dialogue between subsidiary characters) and the scene with the night watchman. They also include descriptive phrasings that derive directly from Pontoppidan’s text in its 1909 version: “The pastor follows her with a frightened look in his childlike blue eyes” (Script I, p. 11; Script II, p. 10) is taken word-for-word from the novel (Pontoppidan 1909, 93), except that the tense has been changed from past to present. The screenplays and the film also seek a more novelistic effect by making extensive use of brief flashbacks to show events recounted or recalled by characters, and they play a significant role in the film’s portrayal of inner life, the way it reveals the main character’s perspective on events, her (metaphorical) point of view.

Script to Screen: Shifting Alignments

The film company produced an elaborate promotional pamphlet for the film, which was also printed in English translation (not always entirely felicitous). It contains a section based on an interview with Brunius, where it is claimed that Pontoppidan collaborated directly on the screenplay:

John Brunius, the stage manager [sic] of “A Mother’s Fight”, had to take into consideration no less than three different film-manuscripts ere he could begin the work of producing the drama. In the first manuscripts, Henry [sic] Pontoppidan, the author of the novel and the film-manuscript, emphasized, more than he really desired, the hard and hostile feelings that dominate the heroine. In the second film-translation, he allowed the mother’s love that induces Thora van Deken to commit a crime to become the predominant motif. The third and last attempt confined itself to mere detail-work. (AB Svenska Biografteatern 1920, 2)

Unfortunately, there is no evidence in Pontoppidan’s surviving letters that he was directly involved in writing the film, nor is it supported by the screenplays, neither of which list Pontoppidan as co-writer. The screenplays we have were very clearly prepared according to professional standards that Pontoppidan would have been unlikely to have mastered; they are laid out as shooting scripts, designed for use during production. Everything is broken down into numbered individual camera setups, with lists at the front where all these setups are sorted by location (with separate lists for exteriors and interiors).

The second of the two versions (Script II) is quite close to the finished film; nearly everything in the film is in the screenplay, although a number of scenes or incidents it describes have been eliminated in the final film. Comparing the different documents with the film clearly shows a process that resembles the one the promotional pamphlet quoted above ascribes to the collaboration with Pontoppidan. The changes gradually remove a number of Thora’s most off-putting actions while at the same time aligning the viewer more closely with her. Let us look at some examples.

The first act of Bergstrøm’s dramatization takes place in Engelstoft’s sick-room, and both versions of the screenplay also start there. The finished film instead goes straight to Thora, sitting in a railway compartment. This choice puts the focus on Thora right from the start, aligning us more closely with her (Murray Smith discusses the importance of a film’s opening in terms of the psychological primacy effect (Smith 1995, 118; see also Bordwell 1985, 38; Sternberg 1978, 93-94)). The film eliminates an introductory scene planned in both versions of the screenplay, showing Engelstoft having a hallucination that contrasts his two wives: his second wife, the vivacious and coquettish Sofie (who has died before the story begins), and his first, the dour Thora, who rests her hand on his chest “like an immense weight” (Script II, p. 2). This vision would have put the blame for the weak heart that kills Engelstoft squarely on Thora, an accusation not raised elsewhere. Furthermore, by eliminating this vision the film avoids aligning us with Engelstoft or trying to make us sympathize with his abandonment of Thora.

The progressive elimination of a number of the many flashbacks planned in the screenplays has the consistent effect of aligning us more closely with Thora and making her less antipathetic. In the first screenplay, there is an extended flashback scene of the first meeting between Thora and Engelstoft; after a ride, he suffers a weak spell because of his heart condition, and Thora helps him. This would have made Engelstoft attracted to Thora for her acts of caring, making her later withholding of them seem more cruel. In Pontoppidan's novel, the attraction between the two is discreetly but clearly understood to be largely physical; the brief flashback we have in the finished film, Engelstoft in huntsman’s dress and holding a horse by its bridle while forcefully pulling the young Thora close and kissing her, is much more in line with this.

The second screenplay also eliminates a flashback showing Thora brutally dismissing one of the foremen at the estate for inefficiency, and another showing Thora and her daughter leaving the manor house after Engelstoft’s infidelity, with Thora denying him the chance to say goodbye to his daughter. The second screenplay still includes a flashback of a grief-stricken Engelstoft at the funeral of his new wife Sofie, dead from a sudden illness soon after their marriage, but this has also been eliminated from the film. Still, at least five flashbacks remain in the sickroom section of the film: Thora recalling her father’s cruel treatment of his family and heedless squandering of the family fortune; her work as a governess and marriage to Engelstoft; her attempts to raise her daughter to be tough; Engelstoft’s infidelity; and the divorce. All of them are prompted by Thora reminding her husband of the reasons for her being hard and suspicious of others, and function as an explanation of her feelings and motivations to us.

Another important change comes later in the story: when Thora discovers that her daughter has become infatuated with the minister, she seeks to separate them. Having learned that he wants to go off as a missionary, she anonymously donates the funds the missionary society needs to finance his trip. In the film, this merely seems like an underhanded ploy to get the minister away from her daughter; but in both screenplays, Thora has a vision of a letter from the missionary society warning that all the previous missionaries perished from swamp fever, the words displayed “in flaming letters,” followed by a cut to a close-up of Thora: “A spiteful, gloating half-smile plays on Mrs. Engelstoft’s lips” (Script II, p. 74) – suggesting that she wishes for the pesky clergyman to die, not just disappear from her daughter’s life.

All these eliminated flashbacks and visions either show Thora being deliberately cruel to others, or they emphasize the feelings of other characters, or both. The cumulative effect of the eliminations is to align us more consistently with Thora, and while we are left under no illusions about the harsh, steely, and unforgiving cast of her character, we do not see her act viciously in ways that might alienate spectators completely from her. The narrative alignment of spectators with Thora is, moreover, not just supported by the construction of the overall narrative, but also the stylistic structuring of individual scenes.

Film Style: Scene Dissection and Point-of-View Structures

The practice of breaking down screenplays into numbered “scenes,” each of which corresponds to a single shot, is consistent with the tableau style prevailing in pre-1920 European films, which relied on extended takes and careful blocking. Thora van Deken, however, is clearly moving in the direction of the emerging classical style and extensive scene dissection. A flashback that shows Thora's discovery of her husband's infidelity is presented in a typical tableau-style shot with a character observing another character in the same shot while remaining effectively hidden behind a piece of scenery and also managing to turn herself largely in our direction, allowing us to see her reaction, even though looking at the people she is observing might seem more realistic.

Interestingly, the screenplays both lay out the scene in several separate shots, cutting back and forth between the husband kissing the other woman and Thora’s horrified reaction. The recasting of the scene in a more tableau-like fashion is likely the result of constraints imposed by scheduling, the design of the set, or similar factors.

Many other scenes in the film are shot and edited as what Murray Smith (1995, 156-57) has usefully termed point-of-view structures (series of shots that include both shots of a character looking at and/or reacting to something, and shots of the object of the character’s look). For instance, the scene of Thora’s husband’s burial is dissected in this way.

It is tempting to link Brunius’ extensive use of both point-of-view shots and flashbacks to the film’s declared ambition to portray inner life, because these devices are often regarded as paradigmatic instances of character subjectivity. While I am no fan of poststructuralist film theory, it is difficult not to be struck by the extent to which Thora is “the bearer of the look” in this film. I would argue, however, that in both poststructuralist theory and Edward Branigan’s highly influential work on Point of View in the Cinema (the title of his 1984 book) misleadingly overemphasize the discursive in their discussion of point-of-view shots and “looks,” neglecting the importance of actors’ performances for the presentation of character subjectivity.

I share the misgivings of the cognitive narratologist Alan Palmer, whose discussions of the notion of point of view I have found particularly insightful. Palmer has written critically about what he calls the speech category approach to literary narrative (Palmer 2004, 13). Here, the key analytical question is: who speaks? Branigan has sought to adopt this focus wholesale to film, even though moving images are not discursive acts equivalent to sentences; they are not uttered by speakers. Nevertheless, when a shot is taken from the position of a character’s eyes, Branigan claims that “the telling is attributed to” that character (Branigan 1984, 73). A searching, soul-baring close-up, on the other hand, is not imbued with any subjectivity in Branigan’s terms: “The character is merely the object of another narration which is non-character in origin. The mere speech or appearance of a character, even if an assertion of a mental condition, without more, is insufficient to establish the character as the source of the space” (Branigan 1984, 75).

To me, it seems entirely mistaken to suppose that a character glancing off in one shot should be regarded as "the source of the space" seen in the next shot. I think that Torben Grodal is quite correct to say that we, the audience, regard the spaces we see in most normal narrative films as coherent, three-dimensional, and stable from shot to shot. Grodal shows that “viewers process moving images by understanding them as cues to perceive objective spaces and objects that exist independently, regardless of the camera’s position, just as we in the real world move eyes and head to soak in information to construct objective, object-centered representations of the world” (Grodal 2009, 241).

Part of the trouble comes from the ambiguity of the notion of point of view, an ambiguity I confess I have exploited for the title of this article. In film, the term POV is firmly ensconced; but we should be wary of collapsing optical point of view with the metaphorical extensions of the notion that refer to feeling, convictions, concerns, and other kinds of subjectivity. As Alan Palmer writes: “Another suggestion that I would make if I were making them is that the term point of view should be restricted solely to the spatio/temporal, perceptual point of view of narrators and characters, and should not be used to describe any other aspects of fictional minds” (Palmer 2007, 470-71). A point-of-view shot may give us information about what has attracted the glancing character's attention, but to say that it is "told" by that character mischaracterizes its function.

When Thora, at the beginning of the film, approaches the manor house where her former husband is lying on his death-bed, the building is first shown to us in a shot that follows after one of Thora looking; but the subjective content here is largely the work of Thora's hard-faced, controlled demeanor. The shot of the darkened manor with the single illuminated window could just as well have been used as an establishing shot not attributed to any character's optical point of view.

Instead of trying to attribute shots to characters’ “telling,” we should take what we might, following Palmer, call the mind-in-action approach. Palmer emphasizes that in our everyday, real-world experience, each of us “constructs the minds of others from the behavior and speech”; with fictional characters, we do much the same: “In one sense […] we are invisible to each other. But in another sense, the workings of our minds are perfectly visible to others in our actions, and the workings of fictional minds are perfectly visible to readers from characters’ actions” (Palmer 2004, 11). While Palmer focuses on literary narrative, where reporting the thoughts and feelings of characters is easy, the cinema allows us a great deal of access to characters’ emotions, intentions, even thoughts – through the performances of the actors. Even naturalistic styles of movie acting, as James Naremore has shown in his Acting in the Cinema, tend to communicate the inner lives of characters with much greater consistency than real-life interactions. In the next section, I shall examine an extended example of the way the film presents Thora’s subjective states using point-of-view structures as well as other means.

Performance: Showing What Is Secret

The perjury scene is a pivotal moment in the story (on the stage, the whole third act took place in the courtroom). Thora has falsely claimed that her husband’s will was burned on his orders just before he died; instead, Thora stole the document. In court, the magistrate has questioned the nurse, who has revealed that nothing could have been burned in the stove in the sickroom, because she had earlier thrown in pieces of cotton wool soaked in rubbing alcohol; they were still there the next morning, showing conclusively that no paper was burned in the stove during the night.

The magistrate asks Thora about the burning of the will, and she maintains that it was burned while her husband was still alive, in his presence. The magistrate’s face (seen in close-up) shows his worry that he has caught her in a lie; he desperately wants her to be innocent. He asks: “In the stove in the bedroom?” After the intertitle, we see him staring intently at Thora, waiting for her answer with bated breath.

We cut to a close-up of Thora taken from an angle roughly corresponding to the magistrate’s optical point of view.

Her eyes dart back and forth; she hesitates; then she replies: “No, in the stove in the next room, in order not to bother the sick man with the smoke.” This is the answer the magistrate had hoped to hear, and he breathes a sigh of relief.

This series of shots show us that despite his intense observation of Thora while she gave her answer, the magistrate has completely failed to notice the seemingly rather evident signs that Thora has realized the question was a trap and that she needed to modify her lie. He has not noticed these signals because they were directed at us, the audience. They are examples of double signaling: in Acting in the Cinema, Naremore discusses how even strongly naturalistic conventions of film acting allow actors “to register conflicting emotions as if they were only thinking to themselves, outside anyone’s view” (Naremore 1990, 75; original emphasis) (articles in Kosmorama #258 by Henry Bacon and Casper Tybjerg give further examples). The use of double signaling is typically supported by a close framing that isolates a character from nearby people who should be able to see the character’s face, and it is good example of the way a film actor’s performance presents “thinking,” the inner states of characters, to the audience.

The climax of the perjury scene comes when Thora must confirm her testimony with a bible oath. She stands up, and Pauline Brunius directs our attention to Thora’s hand by the conspicuous, fraught way she pulls her glove off; the bare hand stands out, white against the black clothes. The magistrate reads a long admonition which also draws our attention to the hand: "The witness stands before the countenance of omniscient God who sees what is secret and exacts retribution openly, he lets the fingers of the hand used to swear a false oath shrivel away." This formulation (which is not in the screenplay, where the admonition instead instructs that the perjurer will be cursed by God) further loads the gesture with significance. The admonition continues: "Raise the three fingers of your right hand with these words: that the testimony I have given agrees with the truth, I hereby confirm with my Bible oath, so help me God and his holy word." The fingers can now become the symbol of the horrible crime she is willing to commit for her daughter’s sake.

In a somewhat distant shot, Thora looks down.

We then get a close-up of Thora’s hand from her point of view. With a crossfade, the hand changes, the fingers becoming grotesquely shriveled and semi-skeletal; after a moment, the hand changes back to normal.

We cut back to a wider shot, this one showing Thora from the side, looking down at her hand while the magistrate and several others look at her.

Only when the magistrate prompts her does she move; as she raises her fingers to swear, we cut to a closer shot of Thora, more or less facing the camera.

When Thora begins to recite the oath, the screenplay called for a cut to a title card with the words, but since they have already been pronounced by the magistrate, Brunius instead decided – brilliantly – to stay on Thora without cutting away to an intertitle, allowing length of the shot to suggest the full force of the act.

The vision of the shriveled hand is the kind of point-of-view shot that appears the most infused with character subjectivity. Point-of-view shots like this are certainly significant, but they must still – like all POV shots – be examined as parts of a point-of-view structure that also includes the shot or shots of the character glancing. Here, it is highly interesting that Brunius chooses not to cut to a close-up, even though the screenplay calls for one:

421.

ENLARGEMENT OF MRS. ENGELSTOFT, who stares at the hand as if petrified". (Script II, 66)

Instead, Brunius cuts to the next, wider shot. By showing Thora surrounded by people observing her calmly, we are immediately reassured that the shriveling of the hand was a private hallucination, not an actual supernatural intervention. We can furthermore see that none of the bystanders seem to react to any sudden change in Thora’s demeanor, showing us that she has been able to suppress any outwardly visible reaction to the horrific vision she has just experienced. What she really feels is withheld.

Again, it is worth underscoring that even in the case of an intensely subjective POV shot like that of the shriveling hand, we are not able to clearly assess what state of mind the character is in before we see her reaction. We get some of it in the long, lingering shot of Thora swearing the oath, where Pauline Brunius’s tense posture and labored breathing show us the effort she must put in to master herself. But only a bit later, when Thora has left the courthouse amongst much whispering from her enemies and is finally alone in her enclosed carriage, do we get to see the full impact of the false oath. Gasping, her upturned eyes watering and shiny, she clutches feverishly at the three fingers with which she swore the oath; at no other point in the film does she let her emotional self-possession slip so violently.

The point-of-view shot of the hand is evidently important to understanding Thora’s inner turmoil, but we need to see her reactions to know that she is tormented by a guilty conscience, not hallucinating because she is drunk or insane. The next section will look at the use of close shots as a key component of the film’s aesthetic strategy in relation to contemporary opinion about close-ups.

Enlargements: Getting Close to Characters

The film repeatedly cuts to closer shots to show us the emotional reactions of characters – especially Thora, but sometimes the daughter, the magistrate, and the minister as well. This extensive use of close-ups in Thora van Deken was, it is worth pointing out, potentially controversial. As Swedish film historians have discussed, there was considerable suspicion towards close-ups among members of the cultural elite (Olsson 1996, 1998; Holmberg 2000). Fiction films were understood as recorded stage plays, and the figures on the screen should accordingly be life-sized. The use of “enlargements,” as close-ups were often referred to, was seen as unnatural and sensationalistic, even scandalous. Fascinatingly, the promotional pamphlet for the film seeks to pre-empt criticism of the use of close-ups. In the section written on the basis of an interview with Brunius, he and his publicist argue against those who would use close-ups as “a weapon against the film” (meaning the cinema, the medium of film as such – I’m using the original English version of the pamphlet where the English phrasings are sometimes not quite correct):

On seeing A Mother’s Fight, the attention is at once caught by the great number of close-ups employed. It is these close-ups that have so often been employed as a weapon against the film by such persons as seldom go to a picture-house and who, debating the matter from a purely theoretical point of view, declare that it is a fault to suddenly interrupt the action, “put the limelight” so to say, on one of the players and show his or her features in an enlarged scale to the public. (AB Svenska Biografteatern 1920, 2)

Brunius goes on to defend close-ups by comparing them to the use of opera glasses:

But John Brunius believes in close-ups. It is nothing else that what the ordinary theatre-goer sees when he uses his opera-glass – and it is just at the most exciting, the most touching moments that the opera-glass is used for the purpose of following more clearly the play of feeling on the actor’s features. In the film, where there is no spoken word to emphasize the action, it is still more reasonable to wish to clearly see the facial expression that is the strong point of both the film and the player. It is then that the enlarged picture places a magnificent opera-glass to the eyes of everyone – opera-glasses a thousand times clearer and more effective than ordinary people can procure. (AB Svenska Biografteatern 1920, 2)

The comparison with opera glasses was a common trope in these polemics which perhaps says more about the social context of the discussion than anything else. It is worth remarking, however, that it takes as given that the primary purpose of the close-up is to give us access to the emotional states of characters through their facial expressions. To Brunius, indeed, the real strength of the cinema lies in its ability to give us access to the minds of characters in this way.

In one instance, the screenplays make it interestingly explicit that close shots are meant to present inner states. Soon after the husband’s burial, we see Thora and her daughter at breakfast. Thora is handed a visiting card by a servant. In a close shot, she looks down at the card; we read the name and the title, "Magistrate." We see her eyes widen and her body tense with dismay and fear (a reaction visible only to us; neither the servant nor the daughter take any notice of it). The visiting card itself could just serve to introduce a new character - a very frequent device in older films - but it has no inherent emotional significance. Thora's reaction reveals the emotional significance it has for her. Knowing her guilty conscience, we can assume that she thinks something along the lines of: The police are at the door! Have they come to arrest me?

In fact, even though the screenplay directions generally try to specify only visible actions and gestures, in this scene it presents Thora’s thoughts directly (the script refers to Thora as Mrs. Engelstoft):

331.

ENLARGEMENT OF MRS. ENGELSTOFT, reading the visiting card.

(The magistrate’s visiting card)

Everything goes black before her eyes. The magistrate? Why would he be here? She reins in her agitation. (Script II, p. 51)

It is evident from these examples that the screenwriters relied on the actor to convey the character’s inner state.

As it turns out, these particular directions come directly from the novel: “For a moment, everything went black before her eyes. The magistrate? Why would he be here?” (Pontoppidan 1909, 134). Here, then, we can see an example of how free direct thought in the novel can be effectively adapted to a searching close-up in the film.

The attention the film pays to showing Thora’s eyes and face is the most important way it aligns us with her, but it also uses point-of-view structures to support the same goal. In two different scenes where the daughter and the minister are alone in the garden, we cut to a parallel scene with Thora; she looks out a window, and we cut back to the garden, bringing it into Thora’s purview and strengthening the feeling that she is at the center of events. The shots of Thora looking do not necessarily make the following shots (or the preceding ones) any more subjective, but the combined effect of the whole sequence is to give us a sense of what is on Thora’s mind.

The end of the film is particularly interesting. As Thora is led out of the manor by the magistrate after confessing her crime, she burns her last remaining personal keepsake: a photograph of her daughter. In the first script, the last shot of the film was a close-up of this photograph slowly consumed by the flames. This ending could easily have been interpreted as Thora psychologically turning her back on her daughter, letting anger at her “betrayal” win out over mother love. This was not the feeling the filmmakers wanted. In the second script, Thora emerges from the manor house, and her domestics look on, the stunned faces of several of them being shown in close-up.

The final film, however, elects not to shift the focus away from Thora in this way. We see her throw the daughter’s photograph into the fireplace, but we do not watch it burn. Instead, we see a long shot of Thora coming out of the house accompanied by the magistrate; no other people are seen. She has to grab hold of the magistrate’s waiting carriage to steady herself. Then we cut in to a closer shot of Thora, breathing heavily, struggling to remain composed. She gazes off into the distance as an iris closes around her face. Then, we cut to a shot of a steamer sailing away. The End.

A few minutes earlier, we have seen the daughter and her minister boarding a ship, and this is presumably the one we now see heading towards the horizon. It is thus part of the objective storyworld. At the same time, by being placed immediately after the final shot of Thora looking towards something far away, it takes on the character of a point-of-view shot, even though we know that Thora is nowhere near the port; instead, it can be understood as her thoughts longingly reaching out for her daughter, even as she recedes into the distance, lost to her forever.

Conclusion

The preceding analysis of Thora van Deken demonstrates that Skandiafilm’s advertising copy was basically right: it is a film where the essential is the portrayal of inner life. It uses a number of different techniques to accomplish this goal. While many flashbacks are simply a device to provide backstory exposition that would have been handled through dialogue on the stage, they decision to remove many flashbacks focused on other characters aligns us more closely with Thora. Point-of-view structures also contribute importantly. In a few cases, they include point-of-view shots that feel markedly subjective (the hand withering and arguably also the final shot of the steamer sailing away), but the main way the film becomes a portrait of Thora’s inner life is through Pauline Brunius’ performance.

As we have seen, Carl Th. Dreyer wrote in 1920 that the distinctive quality of the post-1917 Swedish cinema was that it made film “a medium for true and genuine human representation” (Dreyer 1973, 28). I hope to have shown that Thora van Deken is an outstanding example of precisely this quality. The work of its makers shows us a character’s soul.

BY: CASPER TYBJERG / ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR /DEPARTMENT OF MEDIA, COGNITION AND COMMUNICATION / UNIVERSITY OF COPENHAGEN

Note

1. Bardèche and Brasillach were notoriously fascists (see Kaplan 1986, 2000), but their book was “one of the most influential synoptic histories” in shaping the “standard version” of film history, as David Bordwell has shown (Bordwell 1994, 61).

Works cited

AB Svenska Biografteatern (1920). A Mother's Fight.

Bardèche, Maurice, and Robert Brasillach (1938). The History of Motion Pictures. Translated by Iris Barry. New York, Norton.

Bordwell, David (1985). Narration in the Fiction Film. London, Methuen.

Bordwell, David (1994). "The Power of a Research Tradition: Prospects for Progress in the Study of Film Style." Film History vol. 6 (1): 59-79.

Bordwell, David (1997). On the History of Film Style. Cambridge, Mass., Harvard University Press.

Branigan, Edward (1984). Point-of-View in the Cinema: A Theory of Narration and Subjectivity in Classical Film. Amsterdam, Mouton.

Dreyer, Carl Th. (1973). "Swedish Film (1920)." In Donald Skoller (ed., trans.): Dreyer in Double Reflection: Carl Dreyer's Writings on Film, 21-29. New York, Dutton.

Florin, Bo (1997). Den nationella stilen: Studier i den svenska filmens guldalder. Stockholm, Aura förlag.

Grodal, Torben (2009). Embodied Visions: Evolution, Emotion, Culture, and Film. Oxford, Oxford University Press.

Holmberg, Jan (2000). Förtätade bilder: Filmens närbilder i historisk och teoretisk belysning. Stockholm, Aura förlag.

Kaplan, Alice Yeager (1986). Reproductions of Banality: Fascism, Literature, and French Intellectual Life. Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press.

Kaplan, Alice Yeager (2000). The Collaborator: The Trial and Execution of Robert Brasillach. Chicago, University of Chicago Press.

Naremore, James (1990). Acting in the Cinema. Berkeley, Los Angeles & London, University of California Press.

Olsson, Jan (1996). "Förstorade attraktioner, klassiska närbilder: anteckningar kring ett gränssnitt." Aura vol. 2 (1-2): 34-90.

Olsson, Jan (1998). "Magnified Discourse: Screenplays and Censorship in Swedish Cinema of the 1910s." In John Fullerton (ed.): Celebrating 1895: The Centenary of Cinema, 239-252. London, John Libbey.

Palmer, Alan (2004). Fictional Minds. Lincoln, Neb., University of Nebraska Press.

Palmer, Alan (2007). Review of Dan McIntyre, Point of View in Plays: A Cognitive Stylistic Approach to Viewpoint in Drama and Other Text-types (2006). Style vol. 41 (4): 467-471.

Pontoppidan, Henrik (1909). To Portrætter: Isbjørnen / Lille Rødhætte. Copenhagen, Gyldendalske Boghandel Nordisk Forlag.

Pontoppidan, Henrik (2004 [1900]). Lille Rødhætte. Edited by Flemming Behrendt. Smaa Romaner, 1893-1900. Copenhagen, Det Danske Sprog- og Litteraturselskab / Borgen.

Skandiafilm (1920). Thora van Deken.

Smith, Murray (1995). Engaging Characters: Fiction, Emotion, and the Cinema. Oxford, Clarendon Press.

Sternberg, Meir (1978). Expositional Modes and Temporal Ordering in Fiction. Baltimore, Md., Johns Hopkins University Press.

Tybjerg, Casper (2016). "Searching for Art's Promised Land: Nordic Silent Cinema and the Swedish Example." In Mette Hjort and Ursula Lindqvist (ed.): A Companion to Nordic Cinema, 271-290. Chichester, Wiley-Blackwell.

Suggested citation

Tybjerg, Casper (2017): The Woman’s Point of View: Thora van Deken (1920). Kosmorama #269 (www.kosmorama.org).