When the rain falls, we fall. This line from the promotional trailer (subtitled: Stay Dry, Stay Alive) sets the tone and style for Danish Netflix series The Rain (2018–2020). The series received mostly mediocre reviews from Danish critics but stands out as a success amongst its target audience of young adults, reaching 30 million viewers. This is unique in itself, but The Rain was, in more than one sense, a sign of something new. As a television show produced in a Scandinavian country, The Rain stands out as the first apocalyptic science-fiction production of visual fiction to be played out in a convincing Scandinavian setting with broad national and international appeal. Other Nordic productions, such as the Swedish science-fiction series Äkta människor (2012–2014), created by Lars Lundström, were sold for English-speaking remakes (Humans, 2015), while the original version of The Rain was successfully received in especially South America, Brazil and Mexico. Some of the series’ international appeal is comparable to the appeal of Nordic noir, which offers a view into the exotic world of Scandinavian countries. If Nordic noir explored the cracks in the Nordic welfare state, in its essence, The Rain examines what could happen to its inhabitants if, due to environmental catastrophe, the system were to collapse. The series premiered simultaneously with the real-world crisis of the corona pandemic (2020–), increasing the general interest in fiction thematizing relatable subjects concerning the spread of deadly viruses, as in prepper fiction and post-apocalyptic science fiction. The Rain did this and, in addition, articulated the growing concern for climate change. In that sense, the series points to the potential in the fantastic genres and, more specifically, in what I suggest calling New Nordic Magic as a phenomenon embracing a renewed Scandinavian interest in the supernatural and in science fiction. In what follows, I use the terms magic and fantastic as more or less synonymous.1 It is worth noting that even though The Rain starts out as dystopian science fiction prepper thriller, the series evolves and in its two last seasons changes to touch on superhero tropes including characters with supernatural powers.

New Nordic Magic

The appearance of New Nordic Magic can be understood either as a trend reflecting a new generation of more daring visual storytellers or as a result of a diverse internationalized media market that now includes streaming services and video on demand, in turn allowing greater genre variations and the so-called “glocal” mode of production (Toft Hansen 2020: 84). In addition, the technological means to create convincing visualizations of alternative story worlds has become increasingly affordable and accessible. The concept of New Nordic Magicmay also be explained as a possible reactivation of genres already in existence in early Scandinavian cinema and elsewhere. All these explanations work for The Rain as an example of the sub-genre. I understand the fantastic and magical from an evolutionary biological perspective (Boyd, Clasen, Grodal), which sees our interactions with the hypothetical worlds of fantasy and science fiction as a form of cognitive play or simulations preparing humans for possible, unexpected events such as those occurring inthe series. The formal analysis of The Rain presented here is, to some extent, based on an interview with one of its creators, art director Esben Toft, conducted on a hot summer’s day during the corona pandemic in June 2020.

Nordic style and realism

We can only understand the change that productions such as The Rain have brought to the table with a basic concept of preferred style and genre in the Nordic countries. That said, it is of course impossible to claim any overall Nordic style or genre preference in film and television fiction without gross generalization. Though often seen as a uniform region, the different Scandinavian countries have historically had different approaches to the production of moving images. Swedish film might be associated with the impressionistic, poetic style of the silent age and later in films ranging from Sjöström to Bo Widerberg, while Finland might be related to war films (relating to the civil war and wars against the Soviet Union) or the absurd humor of Kaurismaki. For an international audience, Scandinavian films might again be associated with specific directors belonging to the pantheon, including auteurs such as Bergmann and Dreyer, or to specific trending styles such as the recent Nordic noir. From the point of view of contemporary mainstream audiences, when asked what television series Danish viewers remembered with most affiliation, historical drama series such as Erik Balling’s Matador (1978-1981), Krøniken (Better Times) (2004-2007), and Badehotellet (2013 - ) both created by Hanna Lundblad and Stig Thorsboe topped the list (Astrupgaard & Lai, 2016). If one ignores the exceptional works of Lars von Trier and a few other directors and productions directed at children, mainstream fiction film has mostly, or at least since the late 1940s, been associated with narratives played out in recognizable story worlds characterized by what is broadly considered realism. Well-known acclaimed examples from Denmark range from films such as Ditte Menneskebarn (Ditte, Child of Man, 1946) directed by Bjarne Henning-Jensen to Pelle Erobreren (Pelle the Conqueror, 1987) by Bille August. Still related to realism, the most salient style in recent times is the so-called Nordic noir in films and series ranging from The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo (2009) by Niels Arden Oplev to Forbrydelsen (The Killing, 2011–2014) created by Søren Sveistrup and Broen (The Bridge, 2011–2018) by Hans Rosenfeldt. Differences apart, realism and variations linked to the concept, such as social realism and Nordic noir, are often mentioned when characterizing cinematic style and approaches in Nordic film and television.

According to Birger Langkjær, realism has been considered a kind of mainstream practice in Denmark (2002: 15). Eva Novrup Redvall sees the success of realism in recent Danish television drama and in other Nordic countries in the light of the public service production tradition historically also shaping “kitchen sink” social realism in Britain. She writes:

The public service obligation generally makes representing national life and current conflicts of the people a natural choice and working on a limited budget creates an obvious inclination to turn the gaze towards real or naturalist settings rather than bounding expensive sets (2013: 44).

The idea of realism as a genre is problematized by Roman Jakobson in pointing to the fact that almost all genres or isms from romanticism to futurism have realism in one sense or the other guiding their artistic programs (Langkjær 2002: 15). Even works of fiction not directly related to realism – what we here conceptualize as magic, including fantasy and science fiction – are built on some degree of presumed realism, the magical relies on reconcilable schemas as cause and effect. Marie-Laure Ryan describes the “reality effect” as the principle of minimal departure in any genre. The principle states, Ryan writes, that when readers construct fictional worlds, they fill in the gaps in the text by assuming the similarity of the fictional world to their own experiential reality (1991: 48–60 & Ryan 2014:35). Some degree of realism exists in the fantastic, as the mysterious and fantastic also exist in what is normally considered real. There is a crack in everything, as the song goes. Though mostly realistic, in a way Nordic noir represents a link or a bridge to the mysterious, where the best Nordic noir works as a dark mirror to the seemingly harmonious Nordic society. With New Nordic Magic, we enter the mirror.

On the dark side

Though the genre itself emphasizes visual style, the main attraction of Nordic noir highlighted by non-Nordic scholars and critics is the insight into the social-political reality of the seemingly harmonious Nordic counties (Agger 2012). Nordic noir is about the limitations, the cracks in or the dark sides of Scandinavian welfare systems. Crime stories such as The Killing are often set in darkness, but the ‘noir’ in the label is more than a salute to the classic film noirs. Waade summarizes the characteristics of Nordic noir by three features: 1) Complex characters and a special interest in powerful women and sometimes emotionally dysfunctional main characters, 2) Nordic settings and a special interest in nature, lighting, design and architecture, and 3) social criticism (2017: 7). She then links the special interest in nature and lighting to the concept of melancholia as a salient artistic trend in Scandinavia, which emerged with the birth of cinema in the early 20th century (Ibid: 4).

For Norwegian philosopher Kjersti Bale, the specific melancholic ambiguity involves being simultaneously part of something and outside: displacement and nostalgia (Waade 2017: 4). The sense of longing is again linked to the Nordic light and landscapes: “Scandinavia has a latitudinal position that changes the length of daylight a lot during the year, from the intense summer days when it hardly gets dark at all at night, to the early afternoon dusk and intense darkness of winter” (Löfgren & Ehn in Waade 2017: 6). Melancholia is linked to the romantic mystique and sense of depression that Lars von Trier reflects in his film Melancholia (2011). The Ari Aster horror film Midsommar (2019) in a way built on seemingly paradoxical phenomena such as sunlight at night, which characterizes the Nordic summer. The fantastic deals with paradoxical phenomena of this kind, thrives in twilight and other settings that resonate the ambiguous and obstruct visual orientation, such as fog and rain. The inhibited orientation blocks human action – and may give rise to lyrical, saturated emotions (Grodal 2009: 106). This blocking can also relate to what the Bulgarian literary structuralist Tzvetan Todorov describes as hesitation in the fantastic (Todorov 1975).

Magic, fantasy and science fiction

In Greek, “phantastikos” means producing mental images and is defined as something “existing only in imagination . . . fabulous, imaginary, unreal” (Oxford English Dictionary). With Todorov though, the fantastic is characterized by the special ambiguity we also find as a salient quality in the descriptions about the melancholic explained above. Todorov defines the genre as characterized by a certain doubt in narration, while seemingly supernatural story-events unfold. When confronted, for example, by real demons in the framework of fiction, we characterize it as fairy tale or fantasy. If, in another work of fiction, demons are explained by hallucination or superstition, we characterize it as realism. In the fantastic, we are never sure if the demons are real or not. When faced by the ambiguity, narration hesitates. In short, for Todorov this hesitation is emblematic of or is the first condition of fantastic fiction (1975: 31). It is impossible to address the fantastic or magic in genres without making reference to Todorov though to do so is not unproblematic. On the one hand, he is criticized for having too narrow a view of the fantastic in excluding modern literature and experiments, most notably by Borges and H. G. Wells (Lem 1974), and, on the other hand, for bypassing the popular mainstream genres in general. With Todorov, the fantastic represents only the borderline between the marvelous and the uncanny. However, as Grodal states, we label both the marvelous and the uncanny as fantastic because of the way in which they deviate from standard physics and biology (2009: 105). There is, however, one or two takeaways from Todorov’s concept of the fantastic. As Grodal also points out, Todorov touches on something fundamental in human experience. He deals with stories in which there is a conflict between natural and supernatural phenomena and explanations. Our experience with seemingly paradoxical phenomena, where natural and supernatural explanations collide, triggers what Grodal describes as cognitive dissonance, the conflict between the subternatural and the natural, which has been problematic for humans for thousands of years. It is part of what has driven our mental capacity as species and it lies in the heart of most religions – as well as in popular fiction, such as The X Files (Grodal 2009 44-45).

Daniel Scott addresses the fact that, on the one hand, Todorov might be judgmental in pointing to specific qualities of the fantastic in his somewhat narrow and prescriptive definition, but, on the other, as Scott writes, “ Its metrics is broad enough that it is able to encompass the sub-genres of science fiction and fantasy in one single area, the marvellous” (2018: 21). As one of his examples, Todorov uses Franz Kafka´s The Metamorphosis (1915), which is labeled as science fiction. As mentioned in the introduction The Rain contains both science fiction and fantasy tropes. The series would surely not qualify to Todorov’s high standards in defining the fantastic, but he would not reject it on the basis of being science fiction including fantasy elements. The Rain works as an example of New Nordic Magic not because narration hesitates (it does not) but because it includes both science fiction and fantasy (superhero fiction), and as we shall see, touches on the special relation to the Nordic nature and architecture as well as criticism towards the welfare society.

The Rain and the welfare state

Danish poet Henrik Nordbrandt famously described local seasons as a year including four months of November (1986: 2). And in November it rains. It is one of the most familiar weather phenomena in the Nordic countries, adding to the presumed melancholic mood of the region and to the homogeneous quality of a relatively equal society, cultural geographers might argue. The idea is that water as a life necessity is distributed relatively equally when it rains, making centralized control over water supply less important. The long coastline of the Nordic countries adds to the possibility of relatively equal access to life supply. In contrast, popular story worlds like the ones we experience in David Lynch´s Dune (1984) and in the Mad Max series (1979–2015) by George Miller, push the concept of centralized societies built on water control to the extreme. In The Rain, the drizzle is suddenly deadly. At one level, the familiar turning against you is a frightening and basic trope of horror. Fiction including zombies and the living dead also build on this concept. At another level, the rain that works as one of the fundamentals of the harmonious welfare society we meet in the beginning of the series, here undermines the same system. As such, the series investigates what happens after the collapse of the all-protecting welfare state.

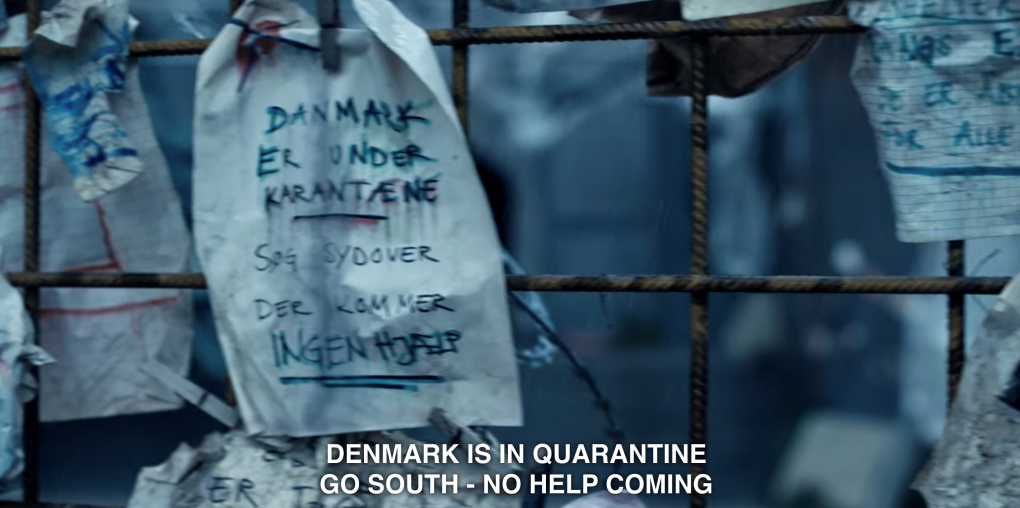

In 2020, The Rain is running in its third and final season as the first Danish-produced Netflix series.2 The series builds on an original idea developed by screenwriter Jannik Tai Mosholt, director and art director Esben Toft Jacobsen and producer Christian Potalivo for Miso Film and Netflix. The Rain premiered in 2018. As a post-apocalyptic prepper thriller, first season of The Rain is played out Copenhagen, the Danish capital’s upland and southern Sweden. In the high-paced plot, the story sets off when Simone and her younger brother Rasmus are warned by their father Frederik to quickly hide in an underground bunker in the forest on the outskirts of Copenhagen, as a deadly rain is approaching the Danish capital. Frederik, who works as a scientist on a secret project for the company Apollo knows the rain contains a highly contagious lethal virus. The fatal consequences of the virus quickly appear as death spreads, causing nationwide panic and chaos. Simone and Rasmus manage to reach the bunker, but for their mother trapped outside, it’s too late. Time passes and years later, Simone and Rasmus leave the underground hideout to discover a completely changed world. Frederik is still alive and working on a cure for the virus. Learning that Rasmus is immune to the virus, the siblings begin a dangerous journey to find their father and, hopefully, help save the human race. On the journey, they are accompanied by other survivors who have learned how to protect themselves from the rain. Danger surrounds the companions, who are also threatened by conflict inside the group, as they walk through the deserted city of Copenhagen and later cross the Øresund Bridge to southern Sweden. Most notably, after crossing the Øresund Bridge, the team is lured into staying with a cannibalistic cult that they eventually manage to escape, only to be welcomed by even greater problems, such as managing to reach Apollo by the end of the first season. As the series evolves the siblings end on opposite sides of the conflict that accelerates as the destruction of nature continue to spread and Rasmus, who is infected by the virus, develops supernatural powers.

Inspiration and theme

As mentioned, the series includes well-known generic story elements recognisable in apocalyptic fiction, such as the journey for a safe haven through eroded landscapes and dangerous decay and encounters with the infected living dead, all tropes known from cartoons, television series, films and literature, such as The Walking Dead (2010- ) created by John Fasano, 28 Days Later (2002) directed by Danny Boyle or The Road (2009) by John Hillcoat. Toft mentions British Colin McCarthy’s film The Girl with all the Gifts (2016) as the main inspiration (Toft 2020). Another trope is that the cure for the epidemic is dependent on and contained in one of the characters. Some critics found the narrative design of the series too obvious and unimaginative, while others disliked the acting of the mostly young cast. We have all seen this before and better, one critic wrote, though praising the series for its high-quality CGI and visualizations of Copenhagen in ruins (Kjær 2018). In Denmark, reviews went from mediocre to bad as season two and three opened. In Politiken, the series was seen as proof that 30 million viewers can be wrong (Grundal 2020). Despite the critics’ verdict, the series remains one of the most viewed foreign non-English speaking series on Netflix. While Danish critics felt that The Rain as post-apocalyptic visual fiction was seen better in international productions, international critics praised it for an original, more human take on the genre. Sam Wollaston from The Guardian wrote: “Not just a knuckle-gnawing, post-apocalyptic thriller ride, not just a series about whether humanity can survive such a catastrophe. It asks whether people can learn to care for and love each other again, establish right from wrong – be human”, (Wollaston 2018). Others found that the portrayal and the intimate relationship between the sibling main characters is what made the series stand out from other post-apocalyptic fiction, again suggesting a more humane take on the genre, just as the Nordic noir might also be seen as a more humane take on the crime genre. (Fienberg 2018)

What makes the series stand out in a Danish context is the fact that it was even made. As suggested, a science-fiction production like The Rain would probably not have been possible in the regime of public service television and difficult to sponsor within the Danish film subsidy system. Art director Toft pointed out that he found it hard to imagine the Danish Film Institute sponsoring the idea, as the institute generally does not fund genre-films – especially if the genre connotes American popular culture such as horror and science fiction (Toft 2020). Producer Christian Potalivo said, “We knew that no big broadcaster in Denmark would have touched it… Budget-wise and target audience-wise, it was out. We put it in a drawer until Netflix came along” (Abend 2019). Cooperation with Netflix was established through screenwriter Mosholt, who had also worked on the Netflix series Rita (2012-2020) created by Christian Torpe and Borgen (2010-2013) created by Adam Price. Netflix liked the idea of producing a series set in a post-apocalyptic Scandinavia. They were looking for material of exactly that kind targeted at young adults. The original idea for The Rain was a feature film set in a near future about a family escaping a nuclear meltdown in Germany, the resulting toxic rain and the breakdown of a society depending on electricity. The family were to travel to a bunker built inside the rocky mountains of Finland for safety. The post-apocalyptic take on the film was to touch upon both the refugee crises and questions on how the subjects of Nordic welfare states would react if the usual support from technology and institutions ceased to exist (Toft 2020). Perhaps because the original concept came too close to the German series DARK (2017-2020) created by Baran bo Odar and Jantje Friese, Toft speculates (2020), the idea of a nuclear meltdown was scrapped and the main setting changed to Copenhagen and southern Sweden. The idea of poisonous rain still remained from the original concept, as did the fundamental premise of challenging the apparent human misconception of total control over and separation from nature.

Designing destruction

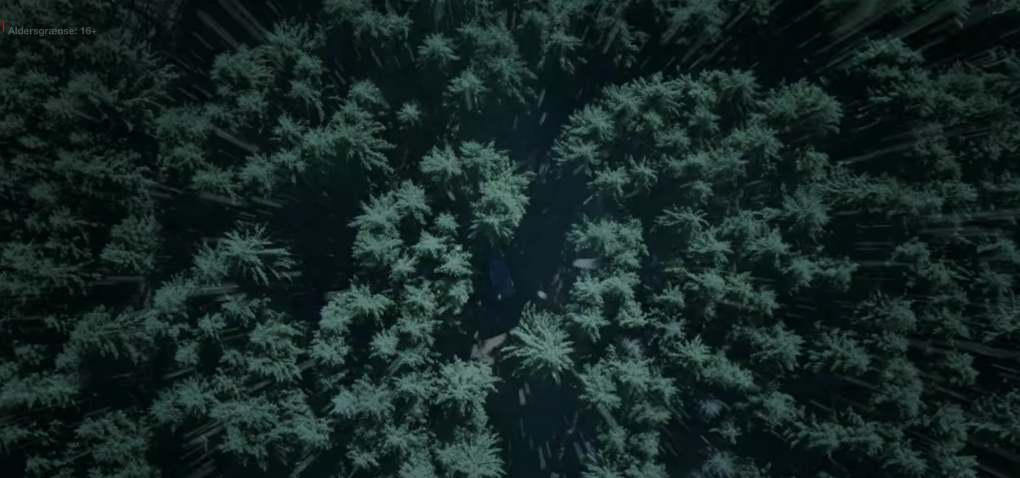

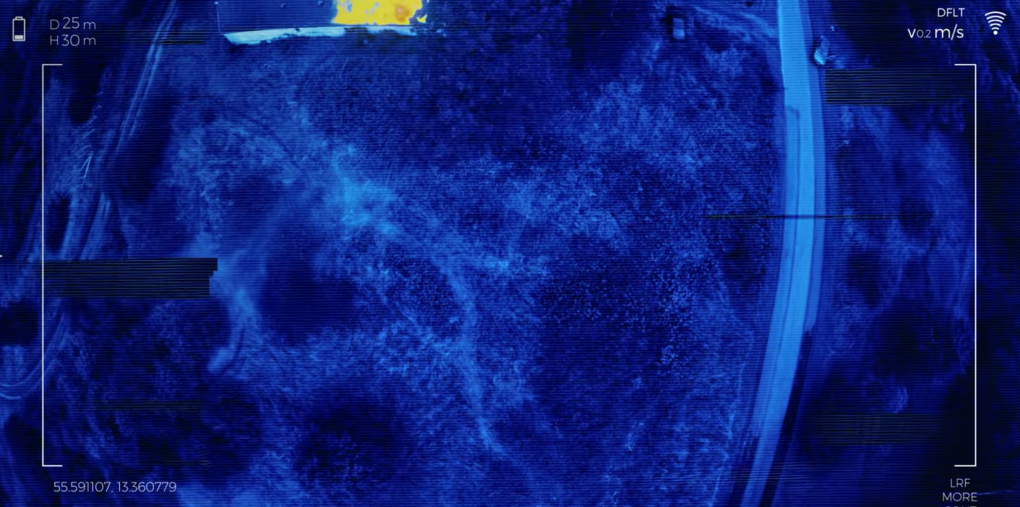

This main idea of a loss of control and nature as an unpredictable force is synthesized in a series of returning key or signature images, including a vertical top-down point of view from the sky as the rain falls. This birds-eye environmental point of view – in effect reminiscent somewhat of Alfred Hitchcock’s original birds-eye point of view from his psycho-environmental catastrophe film The Birds (1963) – is contrasted by the technological point-of-view shots from surveillance drones introduced later in the show. The surveillance drones are used by different parties in the series to map their way through the landscape and to search for possible enemies in their surroundings using heat-sensor cameras. The shots not only maps the story world, they also set up the main contrasts of nature and technology thematized in the series. The creative team wanted to stay true to the core idea of showing human loss of control with nature reacting in new and unforeseen patterns (Toft 2020).

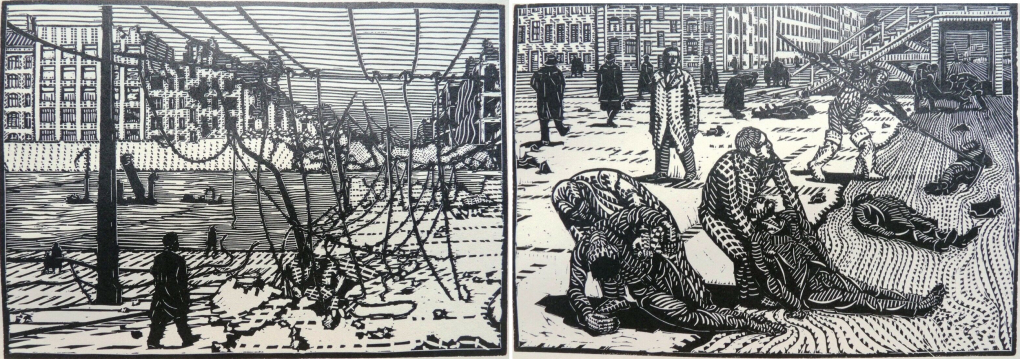

Much research went into the creation of a convincing vision of a post-apocalyptic Copenhagen. While American cities in ruins point to the future, European ruins point to the past. In Danish cinema, exceptions to this rule are few. In 1962, however, Copenhagen was attacked by the prehistoric Godzilla-like dragon Reptilicus (dir. Poul Bang) in a film by the same name. The film was ridiculed to such an extent that it was considered bad luck to even mention its title on film sets. Danish science-fiction film QEDA (2017) directed by Max Kestner visualized a flooded Copenhagen anno 2095. Though images from the film were widely discussed and used in illustrating the debate on climate change, regardless of its qualities, the film reached a modest audience of 4400 people. In a Danish context, the graphic works of Palle Nielsen stand out as visualizations of scenes during or after a disastrous event or war. In his work, experiences from the Second World War, the ongoing cold war, and a possible future nuclear conflict are acutely present. With biblical (and pre-biblical) reference, rain is used as a metaphor for an all-destructive force of change.

As mentioned, The Rain was praised for its visual design. A great amount of work was done to make the transformed world of southern Scandinavia render convincingly. Toft researched theories of urban decay and looked at examples from real deserted cities (Toft 2020). Besides tactile qualities in specific scenes, the totality of the story world is structured around clear thematic contrasts, most notably between nature/culture or technology linked to different locations, the most obvious being the contrast between Danish and Swedish locations. The Danish side, dominated by the urban settings of Copenhagen, is contrasted by the natural settings of southern Sweden. The two sides are separated by Øresund and connected by the iconic Øresund Bridge as a threshold, which is crossed by the group of main characters halfway through the first season, marking it as a turning point in the narrative. In the structure of binary opposites, the bridge works as a mediating link. Intended or unintended, it is also a reflection of The Bridge in the popular Nordic noir series by the same name.

When mapping out the characteristics of Nordic noir, Waade emphasized images of design and modern Scandinavian architecture, often representing values such as transparency, democracy and social equality. In The Rain (in a Danish context), well-known urban landmarks and buildings representing democratic institutions are exposed. One of the series more dramatic scenes takes place in front of the Copenhagen City Hall. In the same episode, a sequence is played out between buildings representing state of the art architecture, Axel Towers, and the entrance to romantic Tivoli Gardens in central Copenhagen. By the end of the first season, when we reach the factory Apollo, it appears as a modern industrial structure built into a natural hill in the Swedish landscape. The design of the facility is inspired by and partly made as a digital composite using elements from the Maritime Museum in Elsinore by the famous Danish architect Bjarke Ingels and his studio BIG. In effect, the urban setting of Copenhagen has been invaded and partly overtaken by nature, just as the natural setting in the Swedish hillside has been invaded by modern architecture. The introduction of different settings on the Danish side works structurally as a graduated series. The Rain sets off in the Copenhagen suburbs, proceeds to the bunker in the forest and finally reach the heart of the Capital, overgrown by plants and trees. Part of the irony surrounding the series is that this green Copenhagen – in The Rain a consequence of catastrophe – somewhat resembles the almost solar-punk visualizations from present city planners visioning a greener city, not as a result of disaster but in order to avoid it.

The pandemic

While visions of a greener Copenhagen might be prophetic, the idea of a mysterious disease of pandemic proportions and a lock down of society certainly was. The corona pandemic and the nationwide lock down in March 2020 struck just a year and a half after The Rain premiered. To Toft, it was both frightening and fascinating to discover some visions of the series coming true in real life during the spring of 2020. The creative team had researched national Danish bio-defense systems and recognized its different levels of emergency preparedness unfold (Toft 2020). In The Rain, events are fiercely dramatized, but Toft and the creative team also wanted to prove or show that the younger generation might have the upper hand during such a crisis (Toft 2020). This remains to be seen, but it is noteworthy that The Rain,and apocalyptic prepper fiction like it, might at least be part of the solution for some during real-life crises. Recent studies conducted during the corona pandemic tested whether past and current engagement with thematically relevant media fiction, including horror and pandemic film, was associated with greater preparedness for and psychological resilience against the pandemic (Scrivner, Johnson, Kjeldgaard-Christiansen and Clasen 2020). The study builds on the explanation inspired by evolutionary biology and cognitive studies on why people engage in frightening fictional experiences, namely that fiction prompts simulations in which one can explore and prepare for similar situations in the real world. As Boyd points out, everything that is exists because it became that way, and this basic concept of evolution works in fiction as well (Boyd 2009: 130). Hence, our mental capacities that enable fantastic experiences evolved because they enhanced our chances of survival through imagination and the ability to visualize alternative future scenarios (Grodal, 2009: 98).

The success of The Rain might be linked to this explanation. Stories that are more relevant to the current state of the world are often more popular, exemplified here by the sudden increase in streaming viewing of the Stephen Soderbergh film Contagion (2011) during the first months of the pandemic. Though not a conclusive study, the research found that fans of prepper genres such as zombie, apocalyptic/post-apocalyptic and alien invasion were significantly more prepared for the pandemic and experienced fewer negative disruptions in their life during the pandemic (Scrivner, Johnson, Kjeldgaard-Christiansen and Clasen, 2020). Aristotle was probably the first to point to the paradox that we find enjoyment in art looking at what we in real life consider disgusting, such as corpses and snakes. The explanation with Aristotle is that in art they are given aesthetic form that enables the enjoyment humans find in learning and in gathering knowledge (Aristotle: Cap IV). The core paradox of horror, of why we, or some of us, enjoy the horrible, is partly explained by this (Clasen). It works as cognitive play that helps us interact with supernatural phenomena and, at least mentally, prepare for possible futures such as the ones dramatized through visual fiction in The Rain.

Concluding remarks

It is tempting to entertain the notion that the modern, relatively well-educated and enlightened northern societies have distanced themselves from the fantastic and colorfully imaginative often associated with the somewhat childish, when faced with the unadulterated light of realism. Historically however, our attraction to seemingly inexplicable phenomena is so deeply rooted that human interest in fantastic fiction did not disappear with the progress of science. On the contrary, genres such as science fiction and horror, which involve significant use of “nonstandard physics”, are even more widespread today than they were in the 1930s (Grodal 2006: 97). Additionally, our most acclaimed film directors explored the fantastic. Lars von Trier debuted with the apocalyptic sci-fi film Element of Crime (1984) and has pursued the genre since, most recently in the previously mentioned Melancholia (2011). Trier is now producing the follow-up on his television ghost story Kingdom (1994- ). Some of Ingmar Bergman’s most highly praised films, such as The Seventh Seal (1957), have fantastic elements. There is no natural unwillingness towards science fiction or the fantastic in the Nordic countries. State subsidy systems for film production and public service broadcasters might have been reluctant toward the genre that (for local national productions) did badly in cinema or contradicted what was thought to be in the spirit of public service agreements.3

During the early years of film production, Scandinavian and Danish films have covered a wider spectrum of genres, including horror, science fiction and even apocalyptic fiction. Canonized works from the silent and early post-silent era, Dreyer’s Vampyr (1932) and Christensen’s Häxan (Witchcraft through the Ages, 1922) included. Early Danish production even embraced big-budget space-travel science fiction and apocalyptic films such as Holger-Madsen´s Himmelskibet (A trip to Mars or 400 Million Miles from Earth, 1918) and Agust Blom´s Verdens Undergang (The End of the World, 1916). In the first decade of the new millennium, the nonstandard genres have also been explored in mainstream film and television productions, such as Skammerens datter (The Shamer´s Daughter, 2014-2018) directed by Kenneth Kainz , Beforeigners (2019– ) created by Anne Bjørnstad and Eilif Skodvin, Ragnarok (2020- ) created by Adam Price and others, including Susanne Bier’s horror science-fiction thriller Bird Box (2018). The pattern is reflected outside mainstream productions in films such as Swedish director Ali Abbasi’s adaptation of John Ajvide Lindquist’s Gräns (Border, 2018), Norwegian director Joachim Trier’s Thelma (2017) and Icelandic director Hlynur Palmson’s Vinterbrødre (Winter Brothers, 2017). The most obvious example might be Thomas Alfredsons romantic horror film Lad den rette komme ind (Let the Right One In, 2008).

In that light, the magic or fantastic films and television series of the millennium are probably best understood as a reappearance or incarnation of preexisting attempts at exploring the magical, as something escaping standard explanatory patterns or examining alternative story worlds. The new platforms provided by streaming services and “glocal” modes of production have undoubtedly helped reaching new generations and a broader international audience.

The Rain stands out as the first apocalyptic science-fiction show to be played out in a convincing Scandinavian setting with broad national and international appeal. The timing of the series was, by chance, coincidental with the real-world crisis due to the corona pandemic and the pandemic increased general interest in fiction thematizing relatable subjects concerning unforeseen events as prepper fiction and post-apocalyptic science fiction and the series, talked to the growing concern regarding climate change. The Rain is not explicit here, but as we have seen, the story world, its visual design and production design, builds on the contact between modern human structures and nature as an unpredictable and unstoppable force. In this way, the series proves its relevance, also on behalf of the genre in total, as having the capacity to address essential problems of the present through the speculative lens of the future. This also points to the qualities of what has been conceptualized as New Nordic Noir.

Elsewhere in this issue, in his article on Beforeigners, Stephen Joyces points to the fact that the story world of recent Nordic fantasy often works as earthbound fantasy that is less about constructing spectacular alternate worlds and more about embedding our world with small touches of the fantastic (Joyce 2021). While it is set in the near future, the story world of The Rain functions as a natural extension of our recognizable current real world. While Beforeigners and Border,embed their fantasy narratives into the deep wealth of Scandinavian history and mythology, The Rain focusses on what happens to people who are used to the safety of the welfare society in the light of environmental collapse. It is suggested that New Nordic Magic in some ways mirror qualities of Nordic noir as summarized by Waade including 1) Complex characters 2) Nordic settings and a special interest in nature, lighting, design and architecture, and 3) social criticism (2017: 7). Using the same parameters addressing character, settling and theme, I would suggest that New Nordic Magic is characterized by three main features 1) human-orientated grounded science fiction or fantasy 2) Nordic settings, architecture and nature often including elements of folk beliefs or mythology 3) thematizing topics of modern society. And - it is tempting to add – quite a bit of rain.

Notes

1. I use the term magic as synonymous with the term fantastic in order to include scenic fiction. This take on the magical is somewhat debatable, but magic can be understood as something not necessarily restricted to fantasy tricks suppressing normal standard physical laws, but also lyrical style and an aesthetic open towards for instance aura (Harper 2015: 88) Additionally, Todorov’s concept of the fantastic is broad enough to include science fiction (Scott 2018: 21).

2. Other series, for instance the comedy show Rita (2012-2020), have been shown on the streaming service. Rita was, however, originally produced for Danish television broadcaster TV2. The series Lillyhammer (2012–14) here works as a prime example of the glocal mode of production in a Nordic context.

3. Recent public-service contracts in Denmark have all included the following headlines for public-service broadcasting on national Danish television. Objectives are defined as: 1) to strengthen the ability of citizens to take part in democratic society, 2) to bring Danes together and to reflect Danish society, 3) to stimulate Danish culture and language, and 4) to deepen knowledge and understanding. The way in which public service is practiced and understood in Denmark is reminiscent of many other European countries, particular the Nordic countries and Great Britain (Nielsen, 2016).

References

Abend, Lisa (2019). “The World Wants More Danish TV Than Denmark Can Handle”. The New York Times. 14/12.

Aristotle: Poetics.

Astrupgaard, Cecilie and Lai, Signe Sophus (2016): “Seernes favoritserier – genrer, narrativer og kulturmøder”. Kosmorama 263.

Agger, Gunhild (2012). Thrillerens Kunst: Forbrydelsen I-III. 16:9 nr. 48.

Boyd, Brian (2009). On the Origin of Stories – Evolution, Cognition and Fiction. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Clasen, Mathias (2017). Why Horror Seduces. Oxford University Press. New York: NY.

Fienberg, Daniel (2018). “The Rain: TV Review”. Hollywood Reporter. 2/5.

Harper, Kristine (2015). Æstetisk Bæredygtighed. Samfundslitteratur. Frederiksberg: DK.

Nielsen, Jakob Isak (2016). “The Danish Way to do it the AmericanWay”. Kosmorama 263.

Henrik, Nordbrandt (1986). Håndens skæven i november. Brøndrums Forlag.

Gregersen, Andreas (2003). “Todorovs fantastiske tøven – En håndfuld tvetydige filmfortællinger”. Kosmorama 231.

Grodal, Torben (2003). “Udøde ånder og levende bytte – Fantastiske film i evolutionær belysning”. Kosmorama 231.

Grodal, Torben (2009). Embodied Visions – Evolution, Emotion, Culture and Film. Oxford University Press. Oxford: UK.

Grundal, Jens (2020). “Ny sæson af det danske Netflex hit beviser at 20 millioner seere sagtens kan tage fejl”. Politiken. 5/8.

Harper, Kristine Hornshøj (2015) ”Æstetisk bæredygtighed”. Samfundslitteratur.

Jensen, Bo Green (2019). “Sære historier om livet på øen”. Weekendavisen. 13/12.

Joyce, Stephen (2021). “Re-Enchanting the Nordic Everyday in Beforeigners”. Kosmorama .

Kjær, Jens Steinicke (2018). “The Rain – anmeldelse”. Ekko. 5/5.

Langkjær, B. (2002). “Realism and Danish Cinema.” In Jerslev, A. (Ed.), Realism and "Reality" in Film and Media (pp. 15–40). Northern lights. Vol. 2002. Museum Tusculanum Press. Copenhagen: DK.

Larsen, Rasmus (2019). “Netflix´s danske success-serie The Rain får 3. og sidste sæson”. Flatpanels.dk. 19/6.

Lem, Stanislaw (1974). “Todorov´s Fantastic Theory of Literature”. Science Fiction Studies. Vol. 1, no. 4, fall 1974.

Redvall, Eva N. (2013). Writing and producing Television Drama in Denmark, From The Kingdom to The Killing. Palgrave Macmillan. London: UK.

Ryan, Marie-Laure (2014). “Story/Worlds/Media: Turning the Instruments of a Media-Conscious Narratology”. In Ryan, Marie-Laure & Thon, Jan Noël (Ed.), Storyworlds across Media: Toward a Media-Conscious Narratology. University of Nebraska Press. Lincoln: Nebraska.

Ryan, Marie-Laure (1992). Possible Worlds, Artificial Intelligence, and Narrative Theory. Indiana University Press. Bloomington: Indiana.

Scrivner, Coltan, Johnson, John A., Kjeldgaard-Christensen, Jens and Clasen, Mathias (2020). “Pandemic practice: Horror fans and morbidly curious individuals are more psychologically resilient during the COVID-19 pandemic”. Personality and Individual Differences. Vol. 168.

Scott, Daniel (2018). “Belief, Potentality, and the Subernatural: Mapping the Fantastic” In Batzke, Ina, Erbacher, Eric C, Heß, Linda M. & Lenhart, Corinna (Ed.), Exploring the Fantastic: Genre, Ideology, and Popular Culture. Transcript Verlag. Bielefeld: Germany.

Todorov, Tzvetan (1975). The Fantastic: a structural approach to a literary genre. Cornell University Press. New York: NY.

Toft Hansen, Kim (2020). “Glocal Perspectives on Danish Television Series: Co-Producing Crime Narratives for Public Service Television.” In Waade, Anne Marit, Novrup Redvall, Eva, and Jensen, Pia Majbritt (Ed.), Danish Television Drama: global lessons from a small nation. Palgrave Macmillan. London: UK.

Waade, A. M. (2017). “Melancholy in Nordic Noir: Characters, landscapes, light and music”. Critical Studies in Television, 12(4).

Wollaston, Sam (2018). “The Rain review – Netflix brings post-apocalyptic thrills to Denmark”. The Guardian. 4/5.

Interview with art director Esben Toft was conducted on Zoom 26.06.2020.

Suggested citation

Wille, Jakob Ion (2021), Hard Rain - New Nordic Magic in Scandinavian film and television fiction. Kosmorama #279 (www.kosmorama.org).

Watch the film at 'Stumfilm.dk: