The production community behind the Danish TV series has been actively engaged in invoking national specificity and Americanization to explain courses of action that lead to a ‘Golden Age’ stretching from Riget (1994, The Kingdom - mini-series) and Taxa (1997-9 – long series) and on-wards (Nordstrøm 2004, Nielsen 2012d). Particularly above-the-line executives have espoused these explanations in a number of contexts – both in Denmark and abroad. A prominent resource is Fra Riget til Bella (‘From Riget to Bella’, Nordstrøm 2004) where sixteen members of the TV production community present their views on production procedures [1]. Extensive interviews with three heads of DR’s fiction/drama division (Ingolf Gabold, Nadia Kløvedal Reich, Piv Bernth) are featured in a thematic 16:9-issue on Forbrydelsen (2007-12, The Killing) (2012a, c-d) and in recent years, key personnel within the production community have been remarkably active in talking about (the success of) Danish television series at festivals, seminars, film schools, and universities. The ‘discourses of national specificity and Americanization’ - as I will refer to them - are drawn from these contexts and from a number of research interviews (see appendix).

Many of the sources are ‘exclusive informants’ (Bruun 2014). From a historiographical perspective, they are key sources. Without their statements we would know less about the historical development of DR’s drama series. However, particularly the heads of DR’s drama division also occupy (or have occupied) a position within the institution that is in the public eye and has built-in communicative tasks. Combined with their frequent participation at seminars, lectures etc., one should be weary of ‘crafted pre-fab sound bites’ or ‘corporate “scripts”’ (Caldwell 2008, p. 3). That does not mean one should discredit them as sources but consider their statements relative to their organizational function at DR and hold their accounts up against production historical as well as aesthetic analyses of DR’s TV series.

Of course, the discourses of national specificity and Americanization are not theoretical constructs thought up by the Danish production community. The concept of Americanization dates back to Samuel E. Moffet’s The Americanization of Canada (1907). Moffet studied the shifting import-export relations between Canada on one hand and Great Britain/United States on the other, for instance how the rail road system, newspaper circulation, telegraph and telephone communication brought Canada into closer relations with the United States compared to Great Britain. More recently, these discourses have fed into the theoretical writings and discussions of globalization and transnationalism (e.g. Hannerz 1996, Tomlinson 1999).

This article de-emphasizes more conceptually oriented discussions and instead analyses the discourses of national specificity and Americanization from three perspectives: 1) strategic positioning, e.g. the ways in which they have been used rhetorically within the production community 2) production practices and 3) production aesthetics (see also Nielsen 1994, Slejborg & Janum 2007 and Redvall 2013 regarding Danish/US production practices).

The American ‘turn’

The advent of TV 2 in 1988 had a strong influence on an ‘American turn’ within DR’s TV series – both dramas and

comedies. Except for local TV channels and cross-border reception in certain parts of Denmark, DR held a monopoly on TV broadcasting in Denmark since its first regular programming in 1951. This changed dramatically within a very brief time span. The legislative framework subtending TV 2 and the limited financial resources in the early years meant that TV 2 did not initially compete directly with DR as regards originally produced series (Berthelsen & Høj 1991, Nielsen 1992) [2]. However, TV 2 successfully acquired American series that were remarkably popular with the younger viewers that DR struggled to hold on to. Beverly Hills 90210, for instance, became an immediate and enormous hit when it was launched on TV 2 in 1992 (Klitgaard 1996, p. 8).

A great deal of TV 2’s initial programming was based on well-established popular formats. For instance, the popular game show Lykkehjulet was adapted from an American format, Wheel of Fortune (1975 - ). This was not the case with drama series produced for TV 2. TV 2’s first fictional series were not launched until 1990-1991 with Jul i den gamle trædemølle (1990, ‘Christmas in the Old Treadmill’) and The Julekalender (1991, ‘The Christmas Calendar’), and they belonged to a highly idiosyncratic genre, namely low-budget satirical Christmas calendar series for adults (Nielsen 2000, Agger 2013). Within TV drama, it was instead DR that first took on well-established American formats such as sitcoms and soaps.

Transitional experiments: US production aesthetics in DR series 1987-1993

DR’s schedule in 1986 and particularly in 1987 showed evidence of focusing on Danish drama in the ensuing competition. Agger notes increases in quantity, a boost of serial forms relative to single TV-films/TV-plays, and an increased diversity of genres represented in DR’s 1987-schedule (Agger 2005, pp. 239-250). The harbinger of things to come was Anders Refn’s Een gang strømer (1987, ‘Once a Cop…’). Commissioned from Nordisk Film, Once a Cop was a precursor to DR’s “miniseries strategy” where The Kingdom is often taken to be the starting point.

It consists of assigning the creative vision to a director as opposed to a scriptwriter; commissioning the production from an external production company typically resulting in crews trained within film production; and appealing to the producers to be innovative in terms of narrative, generic and/or stylistic design (Nordstrøm 2004, p. 42, Nielsen 2012d).

Interestingly, there is little evidence of the last five heads of the fiction/drama division at DR – Ole Bornedal, Rumle Hammerich, Gabold, Reich and Bernth - weaving Once a Cop into the causal mechanisms driving the successful development of DR-drama series. A likely reason is that Once a Cop is considered an anomaly. It was commissioned by DRs TV-Underholdningsafdeling (TV-U, ‘The TV Entertainment Section’), not by TV-Teatret (‘The TV Theatre Section’) and in that sense, Once a Cop belongs to an older tradition within DR where TV-U commissioned series from Nordisk Film such as Huset på Christianshavn (1970-1977, ‘The House in Christianshavn’) and Matador (1978-81, ‘Monopoly’) [3].

What sets Once a Cop apart from these precursors is its audio-visual aesthetics. With its generous dosage of handheld camera movement, tight framing and brisk and ‘dirty’ editing with interspersed jump cuts (Nielsen 2006), the ‘reportage’ style of Once a Cop was akin to historically influential US police procedurals such as Hill Street Blues (NBC, 1981-1987), Homicide: Life on the Streets (NBC, 1993-1999) and NYPD Blue (ABC, 1993-2005). Critics were also quick to point out the American influence (Skytte 1988). Cinematographer Mikael Salomon even migrated to America, first as a cinematographer on high-end film productions such as The Abyss (1989), later a seasoned producer and director of high-profile series. Most significant, however, is the role played by Anders Refn. Refn lifted some of the US-influenced audio-visual signatures of the series into Taxa and to a lesser extent Landsbyen (1991-1996, The Village) before that.

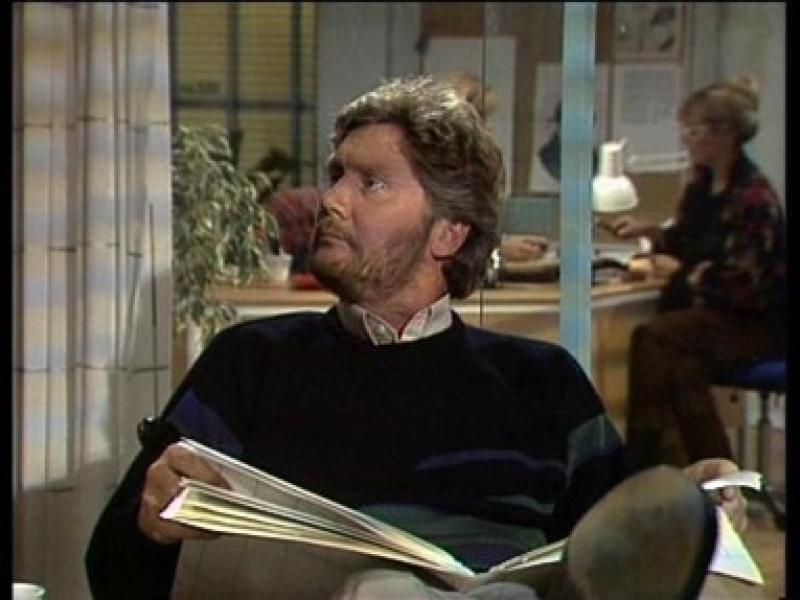

Product development initiatives modelled on American formats were also launched within DR during the transitional years (Nielsen 1990). An example is Dr. Dip (1990), a five-part sitcom written by Ole Bornedal and Nikolaj Cederholm that was to be a traditional multi-camera sitcom filmed before a live studio audience (fig. 2).

Ebbe Iversen in the national newspaper Berlingske Tidende saw clearly the American influence subtending the production (Iversen 1990). The American influence included producing a pilot episode – a novel production strategy within DR at this time (Nielsen 1990).

DR were incorporating new production practices and procedures that they had little training within. For instance, the test screening of the pilot for Dr. Dip (1990) was placed too close to the start of production to make the massive adjustments that the feedback from the audience called for (Nielsen 1990). Furthermore, what organizational unit should house this call for development within DR’s line of TV series? Up until 1990, DR still had both TV-U and TV-Teatret. Birgitte Price headed TV-Teatret from 1985 to January 1990, but series such as Once a Cop and Dr. Dip came out of TV-U. Price did want to shift course away from the single teleplay tradition, but she did not quite know in what direction to turn (Clausen 2015). Experiments with the sitcom genre such as Dr. Dip proved unsuccessful. For whatever reasons – maybe organizational and budgetary ones - Price also failed to take the cue from Once a Cop.

Two of the three long-running series during the early 90s were conceived while Price was at the helm of TV-Teatret: soap opera Ugeavisen (51 episodes, 1990-1991, ‘The Weekly’) and historical drama Gøngehøvdingen (13 episodes, 1992, ‘The Gønge Chieftain’) (‘Danmarks største teater’, 13 May 1990). The third was The Village (44 episodes) initially commissioned by TV 2/Øst from Nordisk Film before DR became involved and finally took over the show [4].

Particularly Ugeavisen was an example of DR attempting to produce more efficiently to counter-balance the high cost per minute of single TV plays (Rowold in Nielsen 1990, Clausen 2015): ‘The production of Ugeavisen began in June 1990. Two episodes per week. Two permanent, big sets, ten small ones in a test studio in TV-byen. 52 episodes of 25 minutes, a production price of approximately DKK 14.000 per minute, that is: dirt cheap’ (‘Fiaskoen der blev en succes’, 15 September 1991). The idea for Ugeavisen came to Jan Ulrich Pedersen and Palle Wolfsberg during the New York Marathon in 1988 while observing a man consumed by a daytime soap opera on a portable TV (ibid.), but the actual series conforms more closely to the tradition of British primetime soap operas such as EastEnders and Coronation Street (fig. 3).

Gøngehøvdingen was described as ‘internationally colourful’ as regards action and erotic escapades (Mohn 1992), but again it had strong ties to British renditions of the swashbuckler genre such as Dick Turpin (Clausen 2015). Similarly with The Village which resembled Emmerdale (BBC 1972-).

The ‘American’ agenda 1993-1997

Today, we tend to think of DR as the driver of the ‘Golden Age’ of Danish TV series. This is undoubtedly correct, but the reorientation of DR’s drama strategy is to a large extent a result of DR looking for ways to handle the increasing competition from particularly TV 2. This is clearly demonstrated in the rhetoric used by Ole Bornedal and to some extent Rumle Hammerich.

In 1993-1994 first Bornedal (July 1993), then Hammerich (October 1, 1994) took charge of the drama division – still a subdivision under TV-Fiktion (‘The TV Fiction Section’) during Bornedal’s brief reign. While Bornedal did little organizationally to change the department around, he - rhetorically and symbolically - represented a turning point. He quickly pointed out that his most important mission was to make the drama division an attractive workplace (Theil 14 August 1993). Eight days later he elaborated, clearly stating his ambition to establish what would later be referred to as cross-over: “Instead of setting aside pools of money for feature film production you should instead invite talented young film makers over to try their hand with the TV-medium […] In my division they can get to work for a large audience, learn their craft - and the mistakes.” (Erlendsson 1993) (regarding cross-over see Redvall 2011).

Bornedal’s public invitation was aimed at new talented filmmakers. Generation ’93 from The National Film School were directors such as Ole Christian Madsen, Peter Flinth, Thomas Vinterberg and Per Fly. Fly states that they were called ‘the American generation’ and adds that there was a shift at the Film School away from Tarkovsky’s wet basements to American fare. Although the new ‘heroes’ were film directors like Francis Ford Coppola, Martin Scorsese, and Robert Altman, they also studied genre classics such as the romantic comedy Pretty Woman (1990) in Mogens Rukow’s scriptwriting seminars (see Schepelern 2004). As a film director, Bornedal himself played a significant role. When Bornedal took the lead of the drama division he was making his feature film debut, the thriller Nattevagten (1994, Nightwatch). Nightwatch became a significant harbinger of one strand of development within the Danish film industry, namely an acceptance and integration of American genre traditions (ibid.). Ironically, he had to go on leave right after starting at his new job in order to finish the film.

Whereas Bornedal’s predecessor, Sigvard Bennetzen, represented a continuation of the TV-Theatre tradition (Clausen 2015), Bornedal embodied a break with that tradition. Bornedal not only had a conciliatory relation to American film genres but also to American TV genres (as illustrated by Dr. Dip). When asked if he would commission a Danish version of Beverly Hills 90210, he replied in the negative but consecutively stated that “an artist with dark rings under his eyes who does not have an audience and sells 200 copies of his poetry collection should seriously consider studying Beverly Hills to find out why people like to watch the show” (Theil 1993). Being a major hit series on TV 2, it was an obvious topic for discussion but nonetheless served Bornedal with a strategic reference point, if not a direct source of influence on the drama series that DR sent ashore.

When Hammerich took over in October 1994, he opposed the over-emphasis on production efficiency that characterized Ugeavisen and strove for a mode of production with genre quality as an integrated motivational factor (Nordstrøm 2014, p. 18) – also practiced in his own work as a film and TV director. Hammerich had a significant influence on the organizational changes within DR, the cutting down of permanent staff relative to free lance-staff, establishing the understanding that DR’s drama series must compete with series produced by commercial players. At the biannual Nordvision meetings, he acted as though DR’s fellow Nordic public service broadcasters were merely one out of many potential co-production/distribution partners (Clausen 2015). He also lobbied successfully to gather the various production units and new studio facilities so that his idea of ‘production hotels’ could be effectuated. He managed to create a ‘mini-Hollywood’: ‘Hollymosen’ (‘The Holly Marsh’) (Gøngemosen was the nickname of TV-Byen, DR’s former headquarters) (Nordstrøm 2004).

Although it was not official DR policy to ‘Americanize’ their drama productions, there was institutional backing behind redirection strategies. DR had lost a substantial portion of viewers to TV 2 between 1988 and 1994 when Hammerich began as head of drama. DR’s current state and future challenges were presented in a report that General Manager, Christian Nissen, initiated prior to Hammerich’s arrival. DR’s Media Research conducted the underlying research on what viewers and listeners thought of DR. Among the striking findings were that DR TV’s weaknesses were ‘entertainment, music, foreign fiction, sport – and probably most disappointingly – Danish fiction, which is simultaneously the area, where most viewers want DR TV to strengthen their efforts’ (‘DR 1995-2005’ 1994, p. 19). This gave Hammerich a decisive mandate to pursue his aspirations with the drama division [5].

Lars von Trier’s miniseries Riget (1994, The Kingdom) was the first major new Danish series to air after Hammerich took over. The Kingdom itself gently mocks American genre traditions. The location and interpersonal conflicts place it within the hospital soap such as General Hospital (ABC, 1963-) and E.R. (NBC, 1994-2009) but only to flaunt its difference from its precursors. Trier himself gives Homicide, Twin Peaks (ABC, 1990-91) and Belphegor (1965) as his sources of influence (Iversen 1994) – three very different series. The Kingdom’s audiovisual aesthetics follow two distinct strands: handheld camera, jump cut-aesthetics, clean sound is generally used during the comedic/satirical scenes of the series; Steadicam, and other measured camera movements together with suspense-enhancing underscore music subtend the horrific and suspenseful segments of the show (fig. 4-6).

After The Kingdom had aired and The Village was coming to a close, Hammerich and producer Sven Clausen looked to the United States for sources of influence regarding the next major series - but not to sitcoms or soaps. Clausen looked to Hill Street Blues and the work of Steven Bochco and David Milch. He became interested in how such a show was actually produced. He first had a chance to become acquainted with Hill Street Blues’ production practices at a seminar in the Fall of 1993 where an international panel including writers and producers involved with Hill Street Blues gave the DR-team a chance to tap into the show’s production practices – for instance the role of the producer versus the director (Clausen 2015).

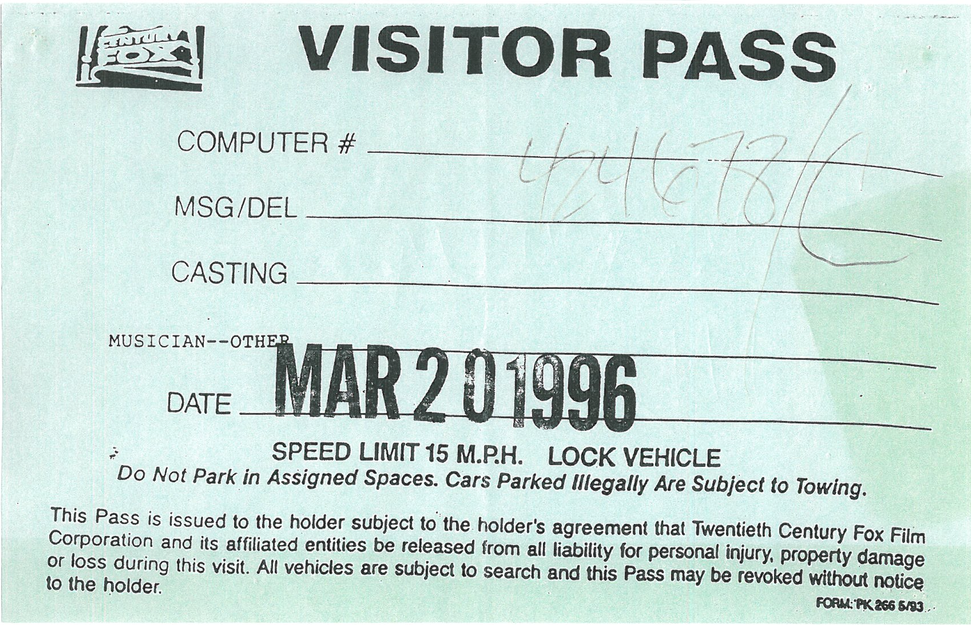

Later, when Taxa was underway, Clausen and director Anders Refn went on a field trip in late March 1996 financed by DR’s Udviklingspulje (‘Development Pool’). Hill Street Blues had gone off air, but Bochco and Milch were instead working on another acclaimed series, namely NYPD Blue, so they spent a week studying the production at Fox Television Studios in Los Angeles (fig. 7).

Clausen notes that it was a tremendously influential week (Clausen 2015). Refn studied camera and lighting set-ups for instance whereas Clausen studied the logistics, production strategies and methodologies (Nordstrøm 2004, pp. 52-70).

Refn and Clausen’s field trip was new in a Danish context but an old phenomenon in a European context. In ‘Imperialism, Self-Inflicted?’, Jérome Bourdon writes of ‘American Television Pilgrimages’ from for instance Britain, Spain and Germany to US sets to study and sometimes steal or imitate American production formats such as quiz shows (Bourdon 2008). Bourdon also recounts various debates across Europe as to the influence of American television on European ‘television cultures’. Bourdon takes this term to mean “a set of professional and organizational practices within national cultures, but with many international interactions” (2008, p. 94). Today these exchanges between television cultures have become a ritualized media consultancy business in the Northern European media industry. Clausen recounts how he assisted in building up such courses (Clausen 2015), but they are now administered and ‘packaged’ by Katrina Wood’s mediaXchange with two annual exchanges on drama and comedy respectively. At DR, but also at TV 2, producers are now typically sent on such exchanges with discussion panels, simulated writers rooms, as well as the possibility of observing a working writer’s room, production on set and production-related meetings (‘Showrunner’, 2015).

To summarize, the ‘discourse of Americanization’ has ties to rhetorical positioning (e.g. Bornedal’s discussion of DR versus Beverly Hills 90210), production practices (e.g. sitcom production practices and Clausen/Refn’s field trip) and production aesthetics (e.g. concrete sources of influence as can we witnessed in Once a Cop). Across these three fields, the discourse of ‘Americanization’ has been weaved into four perspectives:

- Populism: retailoring the audio-visual aesthetics in relation to genre, narrative and style to increase viewer popularity.

- Product Optimization: retailoring production practices for the purpose of production efficiency. This influenced the production plans for Ugeavisen, for instance.

- Professionalization: seeking inspiration from production practices and production aesthetics that are viewed as best practice. This influenced the production plans for Taxa, for instance.

- Recruitment: retailoring production practices or production culture in order to be able to recruit a different set of personnel, i.e. Bornedal’s attempts to lure more film-oriented personnel to work on DR’s drama series.

Public service and the discourse of national specificity

Although DR’s TV series have clearly been influenced by US production practices, the Danish and US production communities could hardly be more different from one another. A striking difference is the presence, underlying cultural-political foundation, financing structure and dominance of public service media in Denmark. From 1992 to 2005, between 75% and 69% of all television viewing was on channels with public service obligations. In the last decade, this has dropped but is still a solid majority of 58% in 2014 (see fig. 8). Another 11% of the viewing in 2014 took place on those of TV 2’s channels that do not have a public service commitment such as TV 2/Charlie, TV 2/News and TV 2/Zulu.

In recent years, a substantial number of Danish TV series have been commissioned for commercial channels such as TV3/MTG (e.g. 2900 Happiness, Lulu & Leon), Kanal 5/Discovery (e.g. Heartless), TV 2 Zulu/TV 2 Networks (e.g. Clown, Tomgang (‘Idleness’), Kristian, SJIT Happens), TV 2 Charlie/TV 2 Networks (e.g. Carmen & Colombo), dk4 (Bødlen, (‘The Executioner')). However, even in these cases, many of the series have received production funding from the Public Service Pool, which is to support public service-oriented programs to be screened on non-license-financed channels (‘Evaluering…’ 2010 & 2014). In other words, the large majority of TV series produced in Denmark are produced under the auspices of public service.

The way in which public service is practiced and understood in Denmark is reminiscent of many other European countries, particularly the Nordic countries and Great Britain. The public service requirements are on display in the public service contracts (DR) and the public service permits (TV 2 Danmark). For instance, recent public service contracts have all contained the following four main headlines with regards to the purpose of DR’s public service broadcasting:

- To strengthen the ability of citizens to partake in a democratic society

- To bring the Danes together and put a mirror up to Denmark

- To stimulate culture and language

- To further knowledge and understanding

(‘Public service…’ 2014, p. 3)

Significantly, the ‘discourse of national specificity’ is an off-shoot of the way in which the drama division at DR (and TV 2) has effectuated these public service obligations with relation to their TV series. The public service contracts specifically address mass: DR must assemble the Danes in front of the television screens. DR’s series are amongst the few programs to achieve this goal, which has been a strong argument for sustaining DR’s economic investment in drama series across periods with cutbacks and crises within the institution (Nielsen 2012a). Whereas this addresses the ‘public’ dimension of public service, the second part of the sentence (to put a mirror up to the Danes) and the three other formulations address the ‘service’ dimension. Although there are various perspectives on what is nationally specific about DR’s series, the specificity discourse emphasizes how public service obligations have tied Danish society into the way in which the series have been produced and viewed within a national context.

National specificity is often espoused by institutional representatives at DR. Piv Bernth, DR’s current head of drama, amusingly stresses the saleability of the explicitly Danish qualities of DR-series by quoting a British producer at the Producer’s Summit in Cannes: ‘My next show will be in Danish. That’s my only way to success’ (Bernth 2014). National specificity is also clearly evoked by Ingolf Gabold’s description of what the headline of the drama division should be when he began as head of the division in 1999: “Danmarksbilleder”, i.e. images of Denmark (Nordstrøm 2004, p. 46, Nielsen 2012d). “Danmark” can be understood as a discursive nodal point (Laclau & Mouffe 2001, p. xi) and particularly series such as Borgen and 1864 have been the bud of much public debate about the (mis)representation of Denmark’s past and present.

Bornedal and Hammerich focused less on this line of argument. Issues of individual temperament are one reason, but more importantly they headed the drama division at a time when the political checks-and-balances regarding DR’s programming were more relaxed (Søndergaard 2006, p. 47-8). The four-yearly public service contracts (not legally binding contracts), for example, had not yet been enforced as a political guiding principle.

TV 2’s position in the market is also relevant to the discourse of national specificity (see below), but it follows a different trajectory. Gabold’s “Danmarksbilleder” can of course be seen as a way of positioning DR’s drama division relative to TV 2, thus attempting to strengthen a brand identity that flows more naturally from DR’s public service obligations than ‘Americanization’. However, since Gabold made little mention of “Danmarksbilleder” publically until late 2003 (Kastrup 2003), it is best understood as a more or less explicit representational strategy within DR’s drama division.

Rhetorically, Gabold has approached the task of creating “Danmarksbilleder” from an inquisitive perspective: e.g. to investigate what it means to be Danish at a given cultural-historical moment. In 2004 he argues that globalization and internationalization do not make conceptions of Denmark and Danish-ness less, but more interesting. Taking on the role of ‘world citizens’, Gabold argues, rekindles an interest in and strengthens a sense of not only national but regional identity (Nordstrøm, p. 46-7).

Gabold also refers to “DR policy” when arguing that for a public service channel it is not sufficient to deliver fascinating and entertaining storytelling but that DR should build a so-called ‘deeper layer’ into their stories that addresses social and ethical dimensions (ibid.). Gabold would later refer to this as the ‘double story’, anchoring the ‘deeper layer’ more specifically to relevant issues in Denmark at the time of production (Redvall 2010): e.g. in connection with Forbrydelsen II, what is it like to be living in a country that is at war in Iraq and Afghanistan? (Nielsen 2012d). Rumle Hammerich also referred to this as the ‘public service layer’ (Bernth 2014).

The ‘double story’ is not merely a dramaturgical exercise. To Nadia Kløvedal Reich, Gabold’s successor, tying the ‘deeper’ social-ethical layer into their series means that the series become invested with a storyline that carries themes that are socially and culturally specific to Denmark. Consequently, to the question ‘what makes Danish TV series travel?’, Reich explicitly claims that is the Danish welfare state that ‘travels’. To use a classic term from trade theory, this would be the essential (dynamic) comparative advantage of Danish TV series in the international market place (Maneschi 1998). In lectures (Reich 2012, 2013) and interviews, Reich refers to the scene in Borgen where Birgitte Nyborg suggests a ‘marriage agreement’ to her husband, Phillip: that he continues to have his ‘intimacy on the side’ but outwardly keeps up the appearance of a happy husband and father to steer Birgitte through political turmoil as Prime Minister:

As a woman she takes hold of a power base that is classically masculine. You would not do that in England, or Germany, or France. And that is about the fact that we built a lot of nurseries and kindergartens forty years ago; that women joined the workforce; it is about the right to abortion, it is about State Educational Grant and Loan Schemes. It is about a whole range of structural elements in Scandinavian society that has meant that the relation between the sexes is what it is today and that women’s liberation and self-actualization are perhaps ten years further ahead here. So if you take that scene and say that ‘here you see the “double story”’, you would not say ‘oh, yes we clearly see that.’ But in the whole way of orchestrating the scene, there is a larger narrative about a welfare state and certain possibilities that have affected the relation between woman and man. (Nielsen 2012a)

Reich has further argued that in other European countries such a scene would have reverse gender roles (Reich 2013). She arguably thinks of certain patterns of behaviour and dialogue: Phillip is the most emotionally affected of the two, Birgitte the more composed and pragmatic; Birgitte is the one to say that she knows Phillip has paid and continues to pay a huge price for her career aspirations; Phillip being the one to complain about Birgitte being absentminded on the home-front and so forth (fig. 9).

Certainly Gabold’s and Reich’s assertions are debatable to say the least. Even if we accept Reich’s analysis of the scene from Borgen, it could be argued that Borgen is the odd-one-out because many of the DR series (and TV 2 series) that have been either sold widely or have been adapted are crime series (Unit One, The Eagle, The Killing, The Protectors, Those Who Kill, Dicte, The Bridge). Are Danish crime series really so different from the international or Nordic traditions of the crime genre? Could Gabold and Reich be downplaying the recognisability of the police procedural and tropes from the crime genre as a central driver that makes these series palatable to foreign viewers? Gabold clearly thinks it is not the crime story of Forbrydelsen I that is the essential driving force of the series (Nielsen 2012d). Interestingly, head writer Søren Sveistrup who does not bear the same institutional responsibility as Gabold has no qualms about arguing that crime is the powerful motor of Forbrydelsen (Nielsen 2012b) (fig. 10).

Furthermore, both Gabold and Reich appear to take the position that cultural history is a force of nature that permeates not only individual agents with artistic agendas but also media institutions and their respective representational strategies. They downplay that both series produced at DR as well as their own metanarratives about the production culture are also discursive constructions of nationhood.

Central to Gabold’s and Reich’s arguments are discussions regarding which Denmark is to be represented in series that carry public service obligations. TV 2 explicitly shifted to locations outside of Sealand in series such as The Julekalender, Strisser på Samsø (1997-98) and more recently in Badehotellet (2013- ), Dicte (2013- ) and Norskov (2015-). Even famous DR series set in the provinces such as Matador, Ugeavisen and The Village did not go more than one hour’s drive away from Copenhagen. In that respect, the shifting locations central to the narrative structure of DR’s Unit One was a way of demonstrating to the Danish population that DR was also ‘present’ in rural towns and areas such as Bornholm, Horsens and Nakskov, for instance. Despite DR’s participation in cross-national TV-productions such as The Bridge (2011- ) and The Team (2015), it is still important for Reich to claim that DR dives down into the nooks and corners of Danish society:

No, we do not think of foreign markets. We only strive to create a series in Denmark, for Danes. That is always our point of departure. The point is not to think of international narratives, but to delve deeper into the matter in terms of what stories Danish society can generate because that is what is interesting out there, also abroad. (Nielsen 2012a)

Piv Bernth concurs. In a recent article on DR’s production culture, Bernth maintains that DR’s stories are anchored in ‘our own cultural backyard’, and about ‘being Danish in Denmark’. Like Reich she claims that this is also the pathway to international appeal: ‘the more local, the more global’ (2016). Since Bernth and Reich maintain the argument about national specificity, it is unclear what ‘local’ means to them. Perhaps it represents a more deeply embedded form of national specificity?

Gabold, Reich and Bernth’s arguments prompt the question: Have DR series become successful internationally because they incorporate traits that make them uniquely Danish? If so, it contradicts a number of theoretical positions as to what makes good export commodities within the world of television distribution. For instance, Serra Tinic (2002) demonstrates how television production practices in Vancouver have de-emphasized national specificity to instead strengthen the appeal of a show on the global (primarily American market) and finally risking a form of cultural homogeneity:

Frustration with federal definitions of national culture, combined with decreasing financial support for regional domestic television production, has led Vancouver producers to move away from the initial nation-building goals of Canadian media policies to take advantage of the Hollywood presence to pursue co-venture agreements with American producers and coproduction projects with international partners to develop programs for global audiences. (Tinic 2002, p. 170)

Tinic’s description comes across as Reich’s nightmare vision - something to be shunned by DR at all costs.

Scott Olson uses the term ‘narrative transparency’ in relation to productions going not into, but out of the US (1999). According to Olson, it is not as much universality or cultural homogeneity that makes something exportable on the global market, but creating audio-visual texts that are sufficiently open so that consumers on various export markets can read their own cultural-historical conditions into the stories. Interestingly, Reich, Bernth and Gabold do not even enlist narrative transparency as an objective.

If Reich’s, Gabold’s and Bernth’s explanations have validity in terms of the impact of Danish series outside of Scandinavia, this does not sit well with the cultural proximity-theory either (De Sola Pool 1977, Straubhaar 1991), i.e. the argument that TV series resonate best with the cultural dispositions of viewers if they exist within the same ‘cultural linguistic’ or ‘geolinguistic’ region (Cunningham et al, 1998, Straubhaar 2003). In fact, the argument would be the reverse, i.e. that series such as Borgen and Forbrydelsen have become renowned outside Scandinavia for being exotic and different. This is implicit in Reich’s argumentation, and Bernth uses precisely the word ‘exotic' (Bernth 2014). This line of argument is supported by publications such as Patrick Kingsley’s How To Be Danish (2012), Michael Booth’s The Almost Nearly Perfect People (2014), Helen Russel’s The Year of Living Danishly (2015) as well as media coverage in the UK and the US – e.g. articles and reviews in high-profile publications such as The New Yorker (Collins 2013) and The New York Times (Stanley 2012). Collins amusingly notes ‘To Brits, Danes are exotic, but, as one Dane told me recently, “not like Hawaii-pineapple exotic”’ (2013). If the ‘Denmark’ represented in Danish series is exotic to British audiences, the remake route that American broadcasters and producers have essentially opted for suggests that this ‘exoticness’ does not hold the same sway over the American market - although the critical reception of Borgen in US media did in fact emphasise a number of the particularities suggested by Reich (e.g. Romano 2012, Collins 2013, Lacob 2012) [6].

DR’s international success and orientation towards international co-funding push an underlying allegation, namely that DR’s drama series are increasingly being developed with an international audience in mind (Jensen, Nielsen & Waade 2016). Such an allegation could undermine the cultural-political backing of DR-series, which explicitly emphasizes DR’s obligations towards a Danish viewership. My argument is not that Gabold, Reich and Bernth purposely engage in Machiavellian double-talk. However, their line of reasoning is a remarkably convenient way of not only aligning DR’s public service obligations with the unprecedented international success of their series, but in fact arguing that the international success is a direct consequence of DR serving its public service obligations.

To summarize, the ‘discourse of national specificity’ has ties to rhetorical positioning (e.g. enlisting ‘national specificity’ at particular historical junctures), production practices (e.g. DRs ‘double story’) and production aesthetics. Across these three fields, the discourse of ‘national specificity’ has been weaved into three perspectives:

- Cultural-Historical: Danish cultural history permeates not only individual agents with artistic agendas but also media institutions and their respective representational strategies.

- Cultural-Political: enlisting policy-related documents to enhance cultural-political legitimacy, i.e. arguing that the obligations written into the public service remit has the result that the aesthetics, themes and values of the series are nationally specific.

- Marketing: The Danish welfare state seeps into the fabric of Danish series in a way that this becomes a kind of unique value proposition in itself.

Significantly, these perspectives can be aligned by arguing that the international success of DR’s series is a direct consequence of serving public service obligations that have built-in ties to a national cultural-historical context.

A hybrid explanation

National specificity and Americanization provide seemingly contradictory explanations as to the success of Danish drama series, but they can be combined: i.e. the causal mechanisms subtending the success of Danish drama series is a particular mix of US-inspired production practices and aesthetic traditions (fuelled by DR’s competition with TV 2) combined with national particularities, e.g. DR’s production dogmas, representational forms that reflect values and gender issues particular to the Danish welfare state.

This ‘hybrid explanation’ is persuasive. For instance, the production practices have not merely migrated to a Danish context. Although Refn and Clausen’s field trip could be seen as a kind of ‘self-inflicted’ imperialism, only certain aspects of NYPD’s production practices could be applied to a Danish context. When Clausen returned, he found it hard to convince DR as an institution of the sheer manpower necessary to run a one-hour series with overlapping episodes in preproduction, production and postproduction (Clausen 2015) along the lines of a season of NYPD Blue. Union regulations prohibited a direct transfer of daily work hours, and the executive producer and head writer had to be separate people in a Danish production context (see also Redvall’s discussion of ‘twin vision’ and the showrunner function at DR, 2013). According to Clausen, no one in Denmark had the clout or expertise of a Steven Bochco or David Chase to manage the two-fold task of serving as a head writer as well as executive producing a long-running series (Clausen 2015). Whereas the standard practice of longer series such as Homicide and NYPD Blue is to use a separate director for every single episode [7], the limited number of film directors willing to bring DR’s ambitions to life also meant that Danish directors had to work in blocks of three (later two) episodes – not unlike the final twenty-five episodes of The Village where Niels Gråbøl, Anders Refn, Kristoffer Nyholm and Hans Christensen each directed their own block of episodes (‘Landsbyen drøner videre’ 1995, Clausen 2015). This practice – with some fluctuation as to the number of consecutive episodes - is still prevalent in Danish series. Furthermore, the practice of letting the head writer direct a few key episodes (as practiced in series such The Sopranos (HBO, 1999-2007), Six Feet Under (HBO, 2001-2005) and Mad Men (AMC, 2007-2015)) has not migrated to Denmark.

Script writer Jeppe Gjervig Gram describes the ‘hybrid explanation’ fittingly: ‘We said, “We're going to do it the American way,” but it took some years to find the Danish way to do it the American way’ (in Collins 2013). Despite its aphoristic spark, an important nuance needs to be added to Gjervig Gram’s analysis. Naturally, there is no one American way but a number of different production practices. This has become particularly true with the popularity of premium and basic cable series – particularly from The Sopranos and onwards where a season typically consists of 12 or 13 episodes as opposed to series on broadcast networks (e.g. ABC, CBS, NBC, FOX) that typically have 20-25 episodes per season.

And in fact, the longevity of the NYPD Blue-production set-up within for instance DR’s drama series was short-lived. Only Taxa comes close to following the traditional US production schedule of launching 20-25 episodes per season starting in the fall and ending the season in the spring. This difference between cable and broadcast series is also one of the reasons why Lars Blomgren of Film Lance argues that the best remake partners in the US for Scandinavian series are basic and premium cable networks – not the traditional broadcast networks (‘Q & A with Lars Blomgren’, 2015). With a small adjustment of Gjervig Gram’s statement, it would read: ‘We said, “We're going to do it the American way,” but it took some years to find [a] Danish way to do it [one of] the American way[s].’

Jakob Isak Nielsen is an associate professor at University of Aarhus.

Research for this article has been conducted as part of the project What Makes Danish TV Drama Series Travel? funded by the Independent Research Council. The annual TV Festivals and Copenhagen Future TV Festivals have been useful resources as have seminars and lectures where representatives from the Danish television industry have appeared (e.g. Helene Aurø, Sven Clausen, Nadia K. Reich, Rumle Hammerich, Karoline Leth and Ingolf Gabold). A number of research interviews have also been carried out that I have either [co]-conducted myself or have been given access to as part of the research project: e.g. Nadia K. Reich, Piv Bernth, Ingolf Gabold, Anders Refn, Sven Clausen, Henrik Hartmann, Katrine Vogelsang, Søren Sveistrup, Charlotte Sieling, Mai Brostrøm, Peter Thorsboe, Peter Bose, Ole Bornedal, Bo Erhardt, Tasja Abel, Jimmy Leavens, Adam Wallensten.

Notes

1. Interview-driven research has been conducted regarding Danish TV series, particularly by Eva Redvall (e.g. 2011, 2013) and Unni From (2003) but I am referring to sources where the production community ‘speaks out’.

2. TV 2 Reklame announced a steep decrease in advertising income for 1991-1993 causing ‘lean years’ (Berthelsen & Høj 1991).

3. DR may be less likely to take ownership of series commissioned from external production companies. Bo Ehrhardt notes that Nimbus had some difficulty in that regard with respect to Broen (Ehrhardt 2014) and Hammerich refers to such productions as DR’s ‘step children’ (‘Nordisk TV-drama’).

4. DR shut down TV-teatret 1 January 1990 when Price’s contract ran out, and integrated the division into Underholdningsafdelingen, which was renamed TV-Fiktion. Henrik Iversen led TV-Fiktion, a division covering everything from opera transmission to music programs and TV drama. Former deputy manager Sigvard Bennetzen headed the drama section of the division 1990-1993.

5. The license settlement (1994-7) also brought added resources to boost the output of drama (Nielsen 2000, p. 215). There was also congruity between Nissen’s and Hammerich’s respective ambitions. Both of them refer to the New Deal-rhetoric of Franklin D. Roosevelt talking about their respective re-orientation plans as something to be launched within the first 100 days of their leadership (Nissen 2007, p. 23, 28; Hammerich in Nordstrøm 2004, p. 15).

6. Bernie Sanders’ use of the Danish welfare state in political debates suggests that it is not without appeal in the US.

7. The first season of True Detective (HBO, 2014) is an exception but with its eight episodes and closed narrative it is essentially a miniseries. Other exceptions include Girls (HBO, 2012) which with its ten episodes per season is reminiscent of Danish drama series. Particularly from Livvagterne (2009) and onwards, ten episodes per season is the standard for in-house productions at DR. With Dicte and Norskov ten episodes per season is also becoming common for TV 2 series.

References

Agger, G. (2005), Dansk TV-drama – arvesølv og underholdning, Frederiksberg: Samfundslitteratur.

Agger, G. (2013), ’Danish TV Christmas calendars: Folklore, myth and cultural history’. In: Journal of Scandinavian Cinema, vol. 3, no. 1, pp. 267-280.

Bernth, P. (2014), Interview conducted by A.M. Waade, 3 June.

Bernth, P. (2016), ‘Ingolf Gabolds påstande om politisk bestillingsarbejde hos DR Drama er vanvittige’. In: Politiken, 6 February.

Berthelsen, A.W.; Høj, I. (1991), ‘TV to år på vågeblus’. In: Berlingske Tidende, 16 December 1991.

Bourdon, J. (2008), ‘Imperialism, Self-Inflicted? On the Americanization of Television in Europe’. In: William Uricchio (ed.), We Europeans: Media, Representations, Identities, Bristol: Intellect.

Bruun, H. (2014), ‘Eksklusive informanter. Om interviewet som redskab i produktionsanalysen’. In: Nordicom-Information vol. 36, no. 1, pp. 29-43.

Caldwell, J. (2008), Production Culture, Durham & London: Duke UP.

Clausen, S. (2015), Interview conducted by J.I. Nielsen, 21 September.

Collins, L. (2013), ‘Danish Postmodern – why are so many people fans of Scandinavian TV?’. In: The New Yorker, 7 January. http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2013/01/07/danish-postmodern Accessed 27 August 2015.

Cunningham, S., Jacka, E., & Sinclair, J. (1998), ‘Global and regional dynamics of international television flows’. In: D. K. Thussu (ed.), Electronic empires: Global media and local resistance, London/New York: Arnold, pp. 177–192.

‘Danmarks største teater gik bort i stilhed’ (1990). In: Politiken, 13 May, PS, p. 4.

De Sola Pool, I. (1977), ‘When cultures clash: The changing flow of television’. Journal of Communication, 27(2), pp. 139–150.

‘DR 1995-2005: Analyse og langtidsplanlægning’ (1994). Date: 2 June. Published in November 1994.

Erlendsson, K. (1993), ‘Der skal være en Happy End’. In: B.T., 22 August, p. 18.

‘Evaluering af public service puljen 2011-2013: perspektiver og anbefalinger’ (2014), Det Danske Filminstitut, February 2014.

‘Evaluering af public service puljen’ (2010), Det Danske Filminstitut, February 2010.

‘Fiaskoen der blev en success’ (1991). In: Ekstra Bladet, 15 September, p. 18.

From, U. (2003), Hvad taler vi om? Danske soaps i genreanalytisk perspektiv. Aarhus University, Det Humanistiske Fakultet.

Hannerz, U. (1996), Transnational Connections: Culture, People, Places. London: Routledge.

Janum, Anne-Mette; Slejborg, Helle (2007), ‘Enterprise og stafet på prøve i advokatserien Forsvar,’. In: Frandsen, Kirsten & Bruun, Hanne (eds.), TV-produktion: nye vilkår. Frederiksberg: Samfundslitteratur, pp. 133-155.

Jensen, P.M.; Nielsen J.I.; Waade, A.M. (2016), ‘When public service drama travels: The internationalization of Danish television drama and the associated production funding models’. In: Journal of Popular Television, vol. 4, no. 1, pp. 91-108.

Laclau, E.; C. Mouffe (2001), Hegemony and Socialist Strategy, 2nd edition, London & N.Y.: Verso.

Lacob, J. (2012), ‘Duchess Endorsed: Forbrydelsen, Borgen, The Bridge: The Rise of Nordic Noir TV’, The Daily Beast, 20 June. http://www.thedailybeast.com/articles/2012/06/20/forbrydelsen-borgen-the-bridge-the-rise-of-nordic-noir-tv.html

Kastrup, M. (2003), ‘Verdensmesteren fra Gyngemosen,’. In: Berlingske Tidende, 28 November.

Klitgaard, K. (1996), ‘Global teen soaps go local: Beverly Hills 90210 in Denmark’. In: Young, November 4:4, pp. 3-20.

Maneschi, A. (1998), ‘The Dynamic Nature of Comparative Advantage and of the Gains From Trade in Classical Economics’, Journal of the History of Economic Thought, 20:2, pp. 133 – 144.

Mohn, B. (1992), ‘TVs billige bras’. In: Politiken, 12 January, PS p. 8.

Nielsen, J. I. (2006). Bølgebryder: interview med Anders Refn. In: 16:9 no. 16 (April).

- (2012a). Den kreative fabrik: Interview med Nadia Kløvedal Reich. In: 16:9 no. 48 (November).

- (2012b). Stort drama på den lille skærm: Interview with Søren Sveistrup om Forbrydelsen I-III. In: 16:9 no. 48 (November).

- (2012c). Solen må aldrig skinne, og Sofie må aldrig smile: Interview with Piv Bernth. In: 16:9 no. 48 (November).

- (2012d). DR-drama som æstetisk spydspids: Interview med Ingolf Gabold. In: 16:9 no. 48 (November).

Nielsen, P.E. (1990), ‘Produktudvikling i Danmarks Radio – en forvekslingskomedie!’, unpublished working paper, Department of Information and Media Studies, Aarhus University.

- (1992), ‘Dansk TV efter monopolbruddet - konkurrencen om seerne og public service i forandring’. In: Mediekultur vol. 8, no. 17.

- (1994), Bag Hollywoods drømmefabrik : TV-system og produktionsforhold i amerikansk TV. Århus: AU. Licentiatafhandling.

- (2000), ‘Dansk TV-fiktion i det nationale bakspejl: TV 2's bidrag’, In: Bruun, Hanne; Frandsen, Kirsten; Søndergaard, Henrik (eds.): TV 2 på skærmen: analyser af TV 2's programvirksomhed, Frederiksberg, Samfundslitteratur.

Nissen, C. (2007), Generalens veje og vildveje: 10 år i Danmarks Radio [Kbh.]: Gyldendal (Narayana Press, Gylling).

‘Nordisk TV-drama: Kreative formler og international succes’ (2013), University of Copenhagen. Participants: Nadia Kløvedal Reich, Ingolf Gabold, Rumle Hammerich and Karoline Leth. Moderated by Eva Redvall and Ib Bondebjerg, 17 September 2013.

Nordstrøm, P. (2004), Fra Riget til Bella: bag om tv-seriens golden age, Søborg: DR (Nørhaven Book, Viborg).

Olson, R.S. (1999), Hollywood Planet: global media and the competitive advantage of narrative transparency. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum.

‘Public service contracts’ between DR and Kulturstyrelsen from 2003 and onwards are located here:

http://www.kulturstyrelsen.dk/medier/tv/dr/public-service-kontrakt/ (Accessed 10 December 2015)

‘Public service permits’ given to TV 2 (from 2003 and onwards) are located here:

http://www.kulturstyrelsen.dk/medier/tv/tv-2danmark-as/ (Accessed 10 December 2015)

‘Q & A with Lars Blomgren’ (2015), Crime Pays Conference, Aalborg. Moderated by Anne-Marit Waade and Jakob Isak Nielsen, 1 October 2015.

Redvall, E. N. (2010), ‘Gabolds vision’. In: Ekko.dk, 24 August 2010.

- (2011), ‘Dogmer for dansk TV-drama’. In: Kosmorama no. 248 (Winter), pp. 180-199.

- (2013), Writing and Producing Television Drama in Denmark. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire et al: Palgrave Macmillan.

Reich, N.K. (2012), ‘DRs produktionsdogmer’, lecture Medielærerforeningens årskursus, Ebeltoft Film College 12 September.

- (2013), ‘Grundlaget og produktionsdogmerne for DRs tv-serier samt DRs ageren på det internationale mediemarked’ (2013), inaugural lecture at Aarhus University, 28 August 2013.

Romano, A. (2012), ‘Borgen: The Best TV Show You’ve Never Seen’. In: Newsweek, 30July. http://www.newsweek.com/borgen-best-tv-show-youve-never-seen-65623

Schepelern, P. (2004), ‘Den amerikanske forbindelse’. In: Ekko #21, 16 April 2004. http://www.ekkofilm.dk/artikler/den-amerikanske-forbindelse/. Accessed 1 August 2015.

‘Showrunner: TV drama series’ (2015), mediaXchange program Fall 2015. http://mediaxchange.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/2015-Showrunner-Drama-Fall-Brochure-150226a.pdf. Accessed 21 September 2015.

Skytte, A. (1988), ‘Et eventyr om virkeligheden’. In: Kosmorama, vol. 34, no. 183.

Stanley, A. (2012), ‘She Seems to Have It All, a Whole Nation in Fact’. In: The New York Times, 11 October. http://www.nytimes.com/2012/10/12/arts/television/borgen-a-danish-political-drama-series-on-link-tv.html?_r=0 Accessed 14 August 2015

Susman, G.I. (ed.) (2007), ‘Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises and the Global Economy, Cheltenham, UK and Northampton, US: Edward Elgar.

Straubhaar, J. D. (1991), ‘Beyond media imperialism: Asymmetrical interdependence and cultural proximity’. In: Critical Studies in Mass Communication, 8, pp. 39–59.

Straubhaar, J. D. (2003), ‘Choosing national TV: Cultural capital, language, and cultural proximity in Brazil’. In: M. G. Elasmar (ed.), The Impact of International Television: A Paradigm Shift, Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Ass., pp. 77–110.

Søndergaard, Henrik (2006), ‘TV som institution’. In: Hjarvard, Stig (ed.), Dansk TV's historie. Frederiksberg: Samfundslitteratur, pp. 25-64.

Theil, P. (1993), ‘Handsken er kastet’. In Berlingske Tidende, 14 August 1993.

Tinic, S. (2002), ’Going Global. International Coproductions and the Disappearing Domestic Audience in Canada’. In: L. Parks and S. Kumar (eds.), Planet TV: A Global Television Reader. N.Y.: N.Y. UP.

Tomlinson, J. (1999), Globalization and Culture. Oxford: Polity.

Suggested citation

Nielsen, Jakob Isak (2016): The Danish Way to do it The American Way. Kosmorama #263 (www.kosmorama.org).