Dreyer would of course have worked on far more Psilander films, since he edited most of the films made at Nordisk from 1915 to 1918, as well as writing title cards and plot summaries for program booklets (Drum and Drum 2000: 44-45; Schröder 2010). In this article, however, I want to focus on Lydia and its historical record.

The holdings of the Danish Film Institute on Lydia include: two copies of the script, a typewritten final draft (Script #1) and a shooting script (Script #2), both with handwritten annotations1 title book no. 9 (one of a series of large, hand-written ledgers containing the text of the intertitles for all Nordisk’s silent films); a souvenir programme booklet; a poster; a ledger recording all posters ordered by Nordisk; a review; and 13 stills. I have also looked at the source novel by Viggo Cavling. In what follows, I will explain what these and other sources can tell us about the film’s plot, its production, and its aesthetics. They tell us something about Dreyer’s choices as a screenwriter, and the novel also gives us an interesting sidelight on Psilander. I also hope the article can function as a model for this kind of film-historical research and a showcase for the richness of the DFI’s archival holdings.

Plot

In Denmark, it was common from 1911 until the 1960s for cinemas to sell printed souvenir programme booklets for the film, containing a cast list, a plot summary, and (usually) images from the film. In the silent period, the plot summaries are generally quite detailed and include the ending. For lost films in particular, this is a precious source, and Mark Sandberg has discussed these Danish souvenir booklets in his article “Pocket Movies” (Sandberg 2001).

Sandberg asks, "How much are these intriguing pocket movies to be trusted?" and answers, not really helpfully, "One swings easily between fetishisation of the programmes as valuable trace-evidence and dismissal of them as irrelevant, extra-diegetic trash" (Sandberg 2001: 20). Sandberg is less interested in assessing the value of the programmes as sources for getting a sense of what lost films were like and more in thinking about a spectatorial experience where two different versions of the narrative were presented: the visual one on the screen and the written one in the programme booklet. Sandberg examines the film Afgrunden (1910) and its programme booklet synopsis, being struck by the written and the visual story being "so much at odds" (Sandberg 2001: 15). The synopsis gives Asta Nielsen's character an elaborate backstory not found in the movie, but skips over the intensely erotic gaucho dance, the film's most famous scene.

Clearly, as Sandberg points out, one should be wary of the literary embellishments found in the programme booklet texts. He also suggests that the texts tend to downplay the more salacious aspects of the films: "the narrative effect of the cinema programmes may have helped soften the impact enough to help the films and the cinema gain legitimacy" (Sandberg 2001: 13). We will look at whether this might be the case with Lydia, where we can compare the synopsis with the script and the intertitle list.

The booklet for Lydia was printed by Fotorama, the distributor. It is approximately 12 by 20 centimeters and 8 pages long - two sheets of paper, printed on both sides, folded and stapled. The paper is rough and there is no separate cover, which is typical of the Danish souvenir booklets from this period. It is not particularly luxurious or elaborate. The first page is a cover page with the film’s title. On the second page is a cast list and a list of the film’s “afdelinger” (sections or scenes), and the remaining six pages are given over to the plot summary, illustrated with three stills. The 8-page, rough-paper format is standard for the souvenir booklets from this period, although the number of stills included may vary - some have none, some have one on every page.

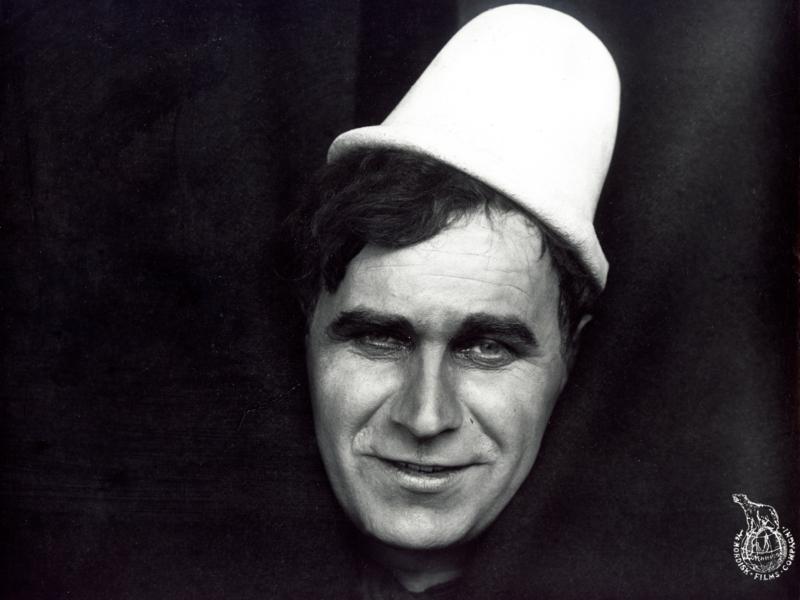

The booklet for Lydia also includes a paragraph of praise for Psilander, printed at the bottom of page 2:

Once more, the incomparable VALDEMAR PSILANDER plays a great tragic role. As the young bank clerk Karl Fribert, who falls hopelessly in love with the celebrated operetta primadonna Lydia, and faithfully and chivalrously puts his deepest feelings on display, following the goal of his love so vehemently that he does not turn back from either theft or murder - here we see Valdemar Psilander put all of his most handsome qualities on display. His noble figure and his manly appearance make us follow him with sympathy, even where his acts should [make us] protest. And when misfortune catches up with him, and he meets death, we feel personally stricken by grief, so real and affecting is his performance.

Here we have the plot briefly outlined. Reading the plot synopsis, we get more detail: Psilander’s character, Fribert, is engaged to Gudrun, a nice girl who works at the same bank as he does; but at the theater, he is utterly besotted with the primadonna Lydia. She is on friendly terms with Kurt, the ne’er-do-well son of Fribert’s employer, Brenge. Kurt invites Fribert to a party, allowing Fribert to make the acquaintance of Lydia. She spurns him; she prefers freedom and luxury to marriage, and she would not consider being with a man who isn’t rich. Fribert tries to move on, but only sinks deeper into despondency. He ends up accepting the offer of a large sum of money from his employer’s rival, Steinwalt: Fribert’s employer holds some documents deeply embarrassing to Steinwalt, and he wants Fribert to steal them for him. Flush with the money he is paid for the theft, Fribert hurries to Lydia. But her affair with

Kurt has had “consequences”. Fribert, incensed, demands of Kurt that he accept responsibility and marry her. He mockingly refuses, and Fribert beats him to death. At the theater, Lydia performs a fire dance. “I dance only for you,” she tells Fribert. She moves closer and closer to the blaze, until her costume and then the whole stage catches fire. Rushing onto the stage, Fribert carries Lydia’s body out of the conflagration and up onto the roof of the theater. After kissing her lifeless lips, Fribert leaps off the roof of the theater to his death.

The souvenir programme booklet synopsis does not strictly follow the course of events of the film that we can reconstruct from the script and the title list. For instance, the synopsis makes no mention of Kurt Brenge before he picks up Lydia at the theater after the performance where Fribert first sees her, only then describing him as "a miserable cad" mooching off his father's wealth. Both script and title list indicate that the film introduced Kurt in a scene at the bank that comes before Fribert’s first sight of Lydia. Furthermore, there are no intertitles that describe Kurt as "a miserable cad" or anything of that sort. We have a descriptive intertitle saying that Kurt "only appears at his father’s firm when he wants to convince him to extend him a new loan" (title 9) and a dialogue intertitles where Kurt says disingenuously, "living is really expensive" (title 10), but beyond that, Kurt's bad character must be inferred. Also, the synopsis gives no reason for why Kurt invites Fribert to his party; nor do the intertitles. In the script, however, it is noted that when they first meet at Kurt's father's bank, they "greet each other like old acquaintances" (Script #2, scene 6 [p. 5]).

Using David Bordwell’s formalist terminology (1985: 49), we can say that the programme booklet synopses do not provide good evidence of the suyzhet of the films, but that they are quite informative about the fabula. Sandberg’s use of the word “fetishisation” to describe the use of the booklets as sources for the stories of lost films is unreasonably disparaging. His cautions about the interpretive framings the synopses provide are worth heeding, however, but we should not jump to the conclusions that the synopses necessarily leave out controversial matters. In the case of Afgrunden – the example used by Sandberg – no verbal description could do justice to the lasciviousness of Asta Nielsen’s gaucho dance, but it is still interesting that the synopsis does not even try.

The aspect of Lydia that one might expect to have been softened, Lydia's pregnancy, is only toned down slightly in the synopsis compared to the intertitles. In the synopsis, we are told that Kurt "has learned that their relationship has had consequences," while the intertitles include a letter from Lydia where she writes: "I need you now that I am going to be a mother" (title 45). Of course, we have no way of knowing how this information might also have been communicated gesturally by the actors. Some fascinating aspects of Lydia go unmentioned in the synopsis, like Kurt’s dark-skinned manservant (he is referred to in the script as a “mulatto”). It would have been interesting to learn to what extent this figure was used to make Kurt seem exotic and perhaps dangerous. The synopsis is a poor substitute for the film itself, but when it can be compared to an intertitle list and a script, it yields a lot of information about the film's storyline. While the screenplay is in many ways the most detailed source, scripts often differ considerably from finished films. The intertitle list and the synopsis are better evidence of the finished film; the title list gives us the best sense of the exact order of scenes in the finished film, but the greater amount of story detail found in the synopsis and the screenplay allow us to understand events which would not be comprehensible from brief snatches of dialogue alone.

Adaptation

The film’s poster describes it as “A love drama in four acts,” naming Psilander and Ebba Thomsen. The director, Holger-Madsen, is named on the cover of the souvenir programme booklet; but neither poster or booklet give any indication that the film is an adaptation of a novel; nor do they name its author. Dreyer’s script (#1) does credit the author (we don’t know about the shooting script (#2); it’s missing the title pages and the first story page). The script title page bears the legend: “LYDIA. Novel by Viggo Cavling”, which also appears on the second page, where Dreyer has added in pencil, “(ved [roughly: adapted by] Carl Th. Dreyer)” (Script #1, [pp. 1-3]).

The novel Lydia by Viggo Cavling (1887–1946) was published in 1914. Cavling was a journalist - his father, Henrik Cavling, was the editor-in-chief of Politiken (where Viggo also worked) and one of the most distinguished figures in the Danish newspaper business. Viggo began working at his father’s paper at age 20 and stayed there for his entire career, a “more philosophical and artistically disposed version of his father” (Bramsen 1983: 342). His original specialty was the ballet, but he would cover all kinds of topics, including a stint on the battlefields of the Western front as a war correspondent; from 1922 till his death, he ran Politiken’s highly successful Sunday supplement, Magasinet (Bramsen 1983: 172, 282,341-43). Viggo Cavling was also an occasional novelist. No less than three of his four novels were turned into films at Nordisk; besides Lydia, they are Pavillonens Hemmelighed (film shot 1914; the novel was published in Swedish in 1916 and in Danish in 1917) and Den skønne Evelyn(1909; film shot 1915). Dreyer wrote all three adaptations; as young and adventurous newspapermen, he and Cavling knew each other, and Dreyer later described him as “my good friend” (1954 radio interview, quoted in Nielsen 2003: 280). In 1912, the two of them had both been involved with the film company Skandinavisk-Russisk Handelshus, and Jan Nielsen has plausibly argued that the two collaborated on the first film scripts credited to Dreyer (Nielsen 1997: 102, 105; see also Nielsen 2003: 275-304).

Cavling’s novels have sunk into almost complete obscurity. Reviewers at the time described Lydia as a pulse-pounding thriller: Freilif Olsen (brother of Henrik Cavling and Viggo’s uncle) wrote that Lydia“presents a veritable superabundance of suspense” (Ekstrabladet, 21 November 1914). Another reviewer similarly wrote: “Events follow headlong upon each other, almost leaving the reader breathless” (Politiken, 20 November 1914, evening edition). To a modern reader, however, the thrills seem few. The prose is serviceable, but the pace is leaden. Cavling spends many pages on describing Fribert’s efforts to approach Lydia, introducing a number of subsidiary characters and unlikely coincidences. In the screenplay, Dreyer has eliminated most of these by making Kurt and Fribert acquaintances from the outset, tightening the narrative considerably.

Before examining the overall character of Dreyer’s adaptation in more detail, it is worth looking at the way he dealt with the most deplorable element of Cavling’s book: the unpleasant whiff of anti-Semitism in the presentation of the villainous banker Steinwalt. He is not explicitly identified as Jewish, but he is introduced as follows:

At the counter, leaning against the mahogany top, stood a small gentleman with an extremely large head. He had a hooked nose and a somewhat receding sallow mouth. The eyes, ensconced behind spectacles, flashed with intelligence and resolve. Despite the heat, the man wore a black overcoat, and on his head he had a stiff, almost angular felt hat of a type rarely seen nowadays. With small hands that resembled the claws of a bird, he had grasped the brass fitting on top of the counter; he stood leaning forward slightly and whispered to young Madsen on the other side of the counter. (Cavling 1914: 62)

He is said to have arrived in Denmark “from Naples” and to have ruined a business partner named Krogmeyer. “Steinwalt was engaged to a poor Russian girl at the time; when Fortune turned in his favor, he sent her home and married Rosenblatt’s daughter. She was ugly, but she brought him two million” (Cavling 1914, 90-91). When Fribert is sent to visit him by his employer, Brenge, he is given a revolver: “Remember, Steinwalt was raised in Italy!” (Cavling 1914: 95).

Dreyer was a lifelong foe of anti-Semitism; his film Die Gezeichneten (Love One Another, 1922) is a deeply felt denunciation of this evil (see Prawer 2005). It is somewhat surprising that he would work with material tainted with this sort of prejudice, but his friendship with Cavling probably took precedence. Dreyer’s description of the Steinwalt character in the screenplay is free of specifically anti-Jewish stereotyping: “a small, southern-looking man with a large head, eyes that flash with intelligence and energy but also with an unusually hard expression” (Script #1, scene 1 [p. 5]). Here, “southern” translates “sydlandsk”, a Danish word which implies “swarthy” when applied to looks, but it is not ethnically specific; it suggests “Latin” as much as anything else. However, we know how Steinwalt looked in the film from one of the surviving stills (identified as still #7 below), where he is talking to Psilander, as Fribert, who looks horrified at the banker’s nefarious proposal. The still shows Peter Nielsen playing the role in make-up that could be seen as evoking an anti-Semitic stereotype.

If we compare the overall trajectory of the story of the novel with Dreyer’s adaptation, we find that they are similar, but differ somewhat in their chronological structure. The action of the novel begins with Fribert already obsessed with Lydia; the scene where he first sees her in the theater and becomes instantly smitten with her is presented retrospectively. By opening the action earlier, Dreyer allows us to see the earlier, normal Fribert, and to present the coup de foudre directly. The most important change from novel to screenplay involves the character of Lydia. In the novel, Lydia is an ingenue, not an established star. She is nineteen years old (169) and lives with her mother; she is flirty and flighty, but fundamentally innocent, and she bears the prosaic last name Brun (“Brown”; 49). Dreyer has renamed her “Erzbach”; in the film, she has become “Lydia Elo”. He has also made her an established star - both script, souvenir booklet, and onscreen cast list refer to her as an “operetta prima donna”. Dreyer’s screenplay describes her as follows: “She is a vision of beauty and grace. Dark, southern beauty. Natural in her movements, slender and supple” (script #1, scene 11 [p. 13]). Instead of living in a modest apartment with her mother and brother, the screenplay has her living in a villa, apparently alone. The screenplay marks her as a calculating femme fatale when she rejects Fribert’s first proposal to her with the following words (the intertitle list follows the script verbatim): “No, I don’t love Kurt. I love freedom and will never be bound by the shackles of marriage. And if I were to be married after all, it would have to be to a very rich man. To me, a life in poverty would be the worst of all.” (Script #1 [p. 33], scene 44; intertitle 35). There is no equivalent speech in the novel.

Another small but significant change is the manner of Fribert’s killing of Kurt. In the novel and the screenplay, Fribert shoots him with a revolver. But a hand-written correction (not in Dreyer’s handwriting) has changed this to “grabs the fireplace lamp and smashes Kurt’s forehead in” (script #1, scene 60 [p. 51]). This makes the act seem more impulsive and less cold-blooded that had Fribert gunned down Kurt - a crime of affect, not a deliberate murder.

The result of these changes is to make Fribert a more sympathetic figure than he is in the book. Cavling’s Fribert is a wretched individual, his obsession with Lydia largely unwanted and unencouraged. Stalker-like, he insinuates himself into her household, neglecting his job, getting deeper and deeper in debt. When Lydia’s mother tries to get him to stop trailing after Lydia, Fribert blames Lydia for causing his obsession:

"Is it my fault? I ask you. No, no, the fault is your daughter's, she is responsible for ruining my career and my life, my ideals and my future, she is to blame for this upheaval which almost has brought me to the brink of madness, she alone —" (Cavling 1914: 256-57)

At the end, of course, Lydia admits that she loves Fribert back, but it is difficult to say if she has become infected with Fribert’s craziness, turning his obsession into a folie à deux, or if Cavling intended this to be a grandly romantic story of amour fou. The book does come across as creepily misogynistic in its romanticisation of a man’s obsessive infatuation and the way it destroys the woman it targets. The film version removes some of Fribert’s most objectionable characteristics and makes Lydia a more strong-willed and calculating character. Dreyer’s adaptation is not only more narratively straightforward than the novel, it also seems less misogynistic because the protagonist’s obsession is less one-sided.

“Drulander”

Cavling’s novel turns out to be an thought-provoking source in a different way. An experienced journalist, he set the novel firmly in recognizable Copenhagen locations (with transparently changed names) and populated it with minor characters that could well be based on real-life observation, unlike the melodramatics of the foreground figures. An unsigned piece in the newspaper Ekstrabladet (where Dreyer worked and where Cavling’s uncle, Freilif Olsen, was editor-in-chief), printed on the novel’s day of publication, presents the author and speculates about the character of the book. “The story is that it is a roman à clef,” the article teasingly observes (Ekstrabladet, 20 November 1914). Fascinating in this context is a long scene describing Lydia’s birthday party where most of the guests are her friends from the theater. They include one “Drulander”, consistently referred to as “Modeskuespilleren” (“the fashionable actor”), and it is certainly tempting to take this figure as a (rather unkind) portrait of Valdemar Psilander.

The character is introduced as follows:

In a knot of people, Fribert noticed Drulander, the fashionable actor, his voice grating as he told a story the ladies took in with wide-mouthed admiration even if they did not understand a word of it. (Cavling 1914: 193)

Kurt the handsome seducer arrives and attracts the attention of the ladies.

Even the fashionable actor felt abandoned for a moment, which caused him right afterwards to continue telling his astonishing story in an even louder voice. (Cavling 1914: 195)

The dinner proceeds.

"The mood had lifted considerably, the gentlemen had put all stiffness aside, and the ladies no longer thought only of their hair and the fit of their gowns. The laughter sounded much louder now, and Drulander the fashionable actor roared out in a voice that could surely be heard down in the street". (Cavling 1914: 201)

Fribert has become annoyed that Lydia uses the intimate second-person pronoun “du” when speaking with Kurt, rather than the more formal “De”. And he is not the only one:

After the meal, the fashionable actor pressed Lydia's hand tenderly and stared long into her eyes.

— An excellent dinner, he said, my compliments! Lydia laughed out loud.

— The food must have been good if it could satisfy you. It cut Fribert to the quick. With this fool too, she used "du". But that had to be the camaraderie of the stage. (Cavling 1914: 206-7)

Lydia’s brother Haagen tries to make an announcement.

"It took a while before people in the corners of the room noticed that someone was speaking. There was still laughter and giggling here and there. The fashionable actor teased the parrot by blowing cigarette smoke at it. Finally, the room fell silent". (Cavling 1914: 209)

The apartment is too small for dancing, he explains.

— Of course we shall dance, Haagen said; but we can't dance in the attic, and we can't dance down here.

— Then we'll dance on the stairs, said the fashionable actor and laughed loudly. (Cavling 1914: 209)

Instead, Haagen announces that the party will move to Kurt’s large apartment by automobile. Fribert is not able to get in the same car as Lydia.

The electrical lamp in the car was not lit, and the couple sitting across from him was enveloped in semi-darkness. As far as he could see, it was the fashionable actor who had found the Rasmussen girl. (Cavling 1914: 210)

They arrive, and the dancing begins:

The fashionable actor, his back hunched, was already pushing his lady across the floor with the modern step, and soon everyone was out. (Cavling 1914: 211)

The fashionable actor does not appear again during the party scene, but he is briefly glimpsed at the theater near the end of the story, when Fribert hastens to Lydia’s dressing room after the murder of Kurt. Fribert is being guided by Lydia’s dresser:

She stopped and pointed out a tall knight in yellow silk standing a little distance away. — That is Drulander, she whispered. (Cavling 1914: 343)

Cavling does not make Drulander a movie actor, but the similarity of the names, as well as the fact that is difficult to find anybody for whom the label “the fashionable actor” would be more apt in 1914 than Psilander, makes the identification of the two very hard to resist. We have very few written profiles of Psilander that precede his untimely death; and while Cavling’s fictionalized account cannot be taken at face value; it does not seem implausible as a pen-portrait of the actor.

Stills

To get a sense of what the film Lydia looked like, we have the evidence of the stills: there are thirteen of them; a fourteenth still only survives as a reproduction in the souvenir booklet. Looking at the stills, the question of the degree to which they correspond to what was actually on screen imposes itself. To try to answer this, I have examined four extant Psilander films and compared them to available stills.

Lydia was one of eight Psilander films made in 1916. For the purposes of this study, I have examined the two surviving Psilander films made in that year (Klovnen, En Skuespillers Kærlighed) and the two (Manden uden Fremtid, En Fare for Samfundet) that survive from 1915’s Psilander film production, and compared them with all available stills. For En Fare for Samfundet, 25 stills were available; for Manden uden Fremtid, 27 stills (there are 29 on the DFI website, but one is a duplicate, and one appears to come from another film); for Klovnen, 26 stills (the remaining five photos on the DFI website are later frame enlargements); and six stills from En Skuespillers Kærlighed (no actual stills survive, but six are reproduced in the film’s souvenir booklet).

Nearly all these stills clearly reproduce a specific moment in the film. More often than not, there is some difference in the framing of the shot. The angle is not quite the same - the stills photographer typically seems to have stood a bit to the right of the film camera. The camera distance also varies; the stills are either a bit closer or a bit more distant than the shots in the film; one may be a full shot, the other a plan americain, but the stills are as often a bit less distant as a bit more. In some cases, for instance En Fare for Samfundet, there is a close-up still that does not correspond to a close-up insert in the film. (En Fare for Samfundet does contain a big close-up of Psilander, but that occurs at a different point in the film).

As far as lighting is concerned, the stills also allow some sense of the use of dramatic, low-key lighting in some scenes, although the effect tends to be somewhat attenuated in the stills I have looked at here. In En Fare for Samfundet, there is a scene where Psilander, wracked by guilt because his late wife’s coffin was destroyed in a fire while he was absent from the house, is staring into a fireplace. Suddenly, the fire burns stronger, and he sees a tiny coffin inside the flames. Horrified, he hurls a book at the fireplace, then staggers out. Neither of the two stills from this sequence - one showing Psilander hurling the book at the fire, one showing him staggering out the door - quite match the dramatic lighting of the scene in the film.

In examining the stills from Lydia, then, we should assume them to give a good feel for the staging of the scenes, but not the actual look of the shot, neither in terms of lighting nor exact framing and angle. One of the stills is really hard to place in the film: it is a relatively close, upper-body views of Psilander, standing in front of a bookshelf with his arms crossed, looking decisive. Since the bookshelf does not appear in any of the other images, it is difficult to say exactly where in the film it belongs, but the location is probably Brenge’s private office, since that (along with the modest home of Gudrun and her parents, which it doesn’t look like) is the most important location not seen in the other stills. I’ll call this still #1 and number the others according to their place in the story.

Still #2 shows a large office. In the foreground lounges Robert Schmidt, elegantly dressed, his silk top hat casually dropped on a counter beside him; Psilander is right behind him, standing stiffly at attention with a pen in his hand, displaying a mixture of servility and disdain. Visible between the two, standing further back, is Zanny Petersen in office-girl attire, looking at the two. This would be scene 6: Kurt, having been given a new loan by his father, cashes in his cheque and chats with Fribert. In Script #1, it is Fribert who cashes the cheque, but in the shooting script, Fribert’s name has been crossed out and replaced with “the cashier”; a handwritten note adds: “Fribert must not be the cashier” (Script #2, [pp. 4-5]).

Still #3 shows a stage with an orchestra pit; extras in alpine dress holding leafy boughs salute a woman in the background. This is scene 11, where Lydia is introduced, dancing a “hymn to spring.” The shooting script contains the handwritten annotation: “Mountain landscape set. Boughs. 10 gentlemen, 10 ladies, 10 children. Swiss [people]. Mrs. Walbom” (Script #2, [p. 8]). In the still, there isn’t quite that many dancers visible, but the director may well have decided that fewer were necessary. Mrs. Walbom was an important figure in Danish ballet, and I will return to her in the final section.

Still #4 shows a large crowd of spectators at a theater (it looks like a film set more than a real auditorium). In the front row sit Zanny Petersen and Psilander, the latter staring intently, his mouth half-open. This is scene 12, where Fribert watches Lydia.

Still #5 shows an opulently decorated apartment, with a divan and Chinese silk draperies. In the foreground, Psilander stares dejectedly into a lit fireplace. Behind him, looking at him, stands Ebba Thomsen in a white gown. A doorway in the background gives a view of another room, where a group of people in evening dress sit and stand around a table. This is scene 30: during a party at Kurt’s apartment, Fribert declares his love for Lydia to her while Kurt is playing roulette with his friends in the other room.

Still #6 shows Ebba Thomsen sitting in front of a fireplace in a different apartment. She is talking on the phone. She has her back turned to Psilander, who sits beside her, an imploring expression on his face. Behind them is a grand piano, and several flower-filled vases decorate the room. This is scene 44, set in Lydia’s apartment. Lydia is talking to Kurt. After she hangs up, Fribert will ask her if she is in love with Kurt, and she will reply that she doesn’t love him, she loves freedom and will only marry a rich man.

Still #7 shows Psilander staring at Peter Nielsen, an appalled look on his face. Nielsen is not looking directly at Psilander; his expression could be the trace of a smile. This is scene 46, where Steinwalt asks Fribert to steal the promissory notes.

Still #8 shows Lydia’s apartment. The angle is a bit different from still #6, but the wallpaper, the piano, and the small picture of a dancer on the back wall are the same. Ebba Thomsen sits with downcast eyes, her hands lying weakly in her lap; Psilander kneels beside her, staring wide-eyed at the camera. This is scene 58, where Lydia tells Fribert that she is with child, and Fribert commits to forcing Kurt to marry her.

Still #9 shows Kurt’s apartment from almost the same angle as in still #5. Robert Schmidt sits on the floor, surrounded by four pretty girls in short dresses; he is telling a funny story or playing a game. Behind them stands Psilander, looking grim and determined. In the room in the background, a chair has been turned over, showing that an animated revel has taken place. This would be scene 59, where Fribert comes to call Kurt to account. In the script, the girls are not part of this scene, though they appear in scene 57a, where they arrive with Kurt to take part in festivities the scripts calls “the orgy” (Script #2, scene 59, [p. 47]). Presumably, the director decided to emphasize Kurt’s callous disregard for Lydia and make it apparent to Fribert, making his murderous rage more understandable.

Still #10 is taken from almost this same position as still #9; the overturned chair in the background is still visible. A figure lies outstretched on the floor, his face turned away from us. Psilander stands to the side looking down at the lifeless man, leaning away in horror, his hands clasped to his heart. This is still scene 59, but now the murder has been done. A table-lamp lies on the floor; in still #5, we can see it standing on a mantelpiece which in this still is just out of frame on the right side of the image. This is strong evidence that the handwritten change in the screenplay from having Fribert shoot Kurt to having him hit him with a lamp was indeed the way the scene was made.

Still #11 shows a corridor decorated with elaborate draperies. Psilander stares furtively at a black man lying insensible in a chair. This is scene 61, where Fribert sneaks out of Kurt’s apartment. The lighting suggests that this scene (like the previous one) would have been dramatically and atmospherically photographed.

Still #12 shows the same stage as still #3; the conductor and the musicians in the orchestra pit are the same. The stage set is a cave; stalactites can be seen on the backdrop, and painted flats of crystals occupy the foreground. A crowd of extras in odd costumes with large, furry headpieces stretch out their arms to an blindingly illuminated figure, a woman with a headpiece and long, gossamer draperies hanging from her arms. This is scene 64, where Lydia dances the fire dance (or possibly 66 or 68, where she moves closer and closer to the fire and finally leaps into it). Reading about the scene in the novel, one imagines some kind of ancient pagan temple, a Salammbô-like ritual, but this set, the handwritten notes in the shooting script reveal, is the elf-hill from Act II of one of the classics of the Danish ballet repertoire, A Folk Tale (Et Folkesagn) by August Bournonville: the notes say “Dec. [abbreviation for “Dekoration” – set] Et Folkesagn.” Below is written, “20 adult trolls, 10 women, 10 children” [Script #2, [p. 52]).

Still #13 is the one that only exists as a reproduction in the souvenir booklet. Psilander is standing behind a grille of some sort, looking dazed; light is hitting his face from an off-screen source, but the rest of the image is quite dark. It is difficult to be certain, but my guess is that this still shows scene 65, Fribert watching Lydia perform the Fire Dance. According to the screenplay, Fribert watches from a special box, “gitterlogen” [“the grille box”], set in the proscenium arch, very close to the stage (Script #2, [p. 53]). The box is hidden behind a grille and allows actors who are not performing to observe the stage without being visible from the auditorium. This would explain both the grille, the off-screen illumination, and Psilander’s ecstatic expression.

Still #14 shows a rooftop, the only exterior in any of the stills. Ebba Thomsen lies lifeless on the roof, Psilander, mad-eyed, kneels next to her, clasping his forehead. This is scene 76, where Fribert realizes Lydia is dead and, according to the screenplay, goes mad. A moment later, he leaps to his death.

We may add the image on the poster to this visual record. It seems to be based on a still and shows Psilander looking hauntedly off to the side while Ebba Thomsen sits beside him, decked out in a headdress and an elaborate gown, looking fearfully and imploringly up at him. There is no background, but we can identify the scene with the help of Nordisk’s surviving poster order book (NF XI, 30). Here, the poster image is identified as “Psilander visits the prima donna in her dressing room” (p. 6) which would indicate that this is scene 62, where Fribert arrives in Lydia’s dressing room and tells her that he has murdered Kurt, and she realizes her love for him.

The stills allow us to get a certain sense of what the film was like visually, and the action they depict can in most cases be identified unambiguously with the help of the screenplay. The screenplay, in fact, yields a great deal of further information about how a film like this was staged and shot.

The tableau aesthetic

As noted above, two typewritten copies of the screenplay for Lydia survive. One, script #1, is complete, while the other, script #2, is missing the first pages. Script #2 is a shooting script, a later version intended for use during production. It has been retyped, with a couple of lines with room to write in special costumes and props added at the top of each numbered scene. Changes made by hand in script #1 have been incorporated in script #2. For instance, scene 18 in script #1 has been crossed out in pencil; in script #2, the scene has been eliminated, although the original scene numbering has been maintained - scene 17 is thus followed by scene 19.

This suggests that the breakdown of the script into numbered scenes was an important part of the production planning process. In his discussion of scriptwriting practices at Nordisk, Stephan Schröder writes: “A ‘scene’ was defined as a spatiotemporal unit and not broken up into several shots; techno-text indicating camera movement or angle, the size and duration of shots and their conjunction, and enframement, and so on were rather rare” (Schröder 2006, 111). Schröder ascribes this to “the actual state-of-the-art of screenwriting” not being “too sophisticated” (Schröder 2006, 111). But other screenwriting traditions also eschew specifying camera placement and the like, because decisions about that is the province of the director. In the case of Lydia, there is a certain breakdown, suggesting that each numbered scene was thought of as one camera setup and one continuous shot, although inserts are not necessarily separated out.

For instance, when Fribert first sees Lydia, the script is broken down as follows.

- Scene 10 begins with an intertitle: “That night at the theater.” Fribert and Gudrun in the stalls.

- Scene 11. The stage. Lydia comes in.

- Scene 12. The stalls. The audience is enraptured. “In close shot [“Nærfotografi”] one sees the seats that Fribert and Gudrun occupy. Fribert has bent forward a bit and sits wide-eyed, his mouth half-open.”

- Scene 13. “Continuation of 11.” Lydia finishes her dance.

- Scene 14. The stalls. Applause. Fribert is stunned. (Script #2, [pp. 9-11])

In modern-day practice, a shot-reverse shot sequence like this, set in one place (even if the stage and the stalls may not in reality be the same location), would be considered one scene. Here, it is divided up; when scene 13 is called “Continuation of 11,” it even suggests that the two would be shot as a continuous take, with the reaction shot or shots cut into it.

This also suggests that the assumptions of the tableau aesthetic were integrated into the screenwriting practices at Nordisk: scene-shots were considered the basic units of planning and shooting. Occasionally, directors would decide to add inserts or dissect scenes into several shots. We can see this in Dreyer’s shooting scripts for his own films, where scenes are broken down into several shots; hand-written notes on the blank left-hand pages of the scripts then record the contents of each shot, numbering them, for instance, 18, 18a, 18b, 18c (Præsidenten, script, [p. 14]).

In the shooting script for Lydia, scene 12 has not been broken down into more than one shot, so there may not have been the cut-in to a close-up that Dreyer's script would lead us to expect. In script #1, the scene where Lydia talks to Kurt on the phone includes the following passage: "Inserted image of Kurt at a phone." In ink, the handwritten indications "44a" and "44b" have been added before and after this sentence (script #1, scene 44 [p. 33]). In the shooting script, they have been typed up as separate scenes, still with the same numbers (script #2, [p. 31]).

It seems relatively safe to assume that Lydia was also made in the same tableau style that characterized Nordisk’s output in 1916, with axial cut-ins to closer shots being used on a few, rare occasions – generally scenes of high emotion – but otherwise keeping the camera relatively far back and letting scenes play out in continuous shots. In their book Theatre to Cinema (recently republished online), Ben Brewster and Lea Jacobs discuss a scene from the Psilander film Klovnen where this pattern is used (Brewster and Jacobs 1997: 103-107). David Bordwell has described the elements of the style in his article “Nordisk and the Tableau Aesthetic” (Bordwell 2010), and the stills provide further evidence that Lydia did indeed utilize a number of these elements.

One important element is the use of the “deep cinematic playing space.” This can be seen in still #2, where Zanny Petersen stands quite far back from Psilander and Robert Schmidt, but is placed exactly between them so that we can see her observe them. Bordwell also talks about the “aperture effect,” where an opening in the background allows us to see a space far back. Kurt’s apartment (stills #5, #9, #10) is clearly constructed to work in this way; in still #5, in particular, we can see the roulette game going on in the back room while the two main characters interact in the front room.

In several of the stills, Psilander assumes the kind of conventionalized poses Brewster and Jacobs describe in the discussion of pictorial acting. They note that there are more poses in serious films like Lydia: “But even within serious films, poses become more pronounced at climatic moments, as if the actors are ‘saving’ them for the big scenes” (Brewster and Jacobs 1997, 103). The Danish theater historian made a similar observation, specifically regarding Psilander, in Klassisk skuespilkunst, his detailed study of the use of conventionalized acting until the beginning of the 20th century (Christiansen 1975: 288). We can see it both in still #10, where he holds both hands to his chest in shock after the murder of Kurt, and in still #14, where he clutches his forehead in despair at the realization that Lydia has died.

Focusing on these poses, however, probably gives a misleading impression of Psilander’s performance. Psilander is “an actor who normally employs discreet means,” as Christiansen says (Christiansen 1975: 288). To get a sense of how Psilander would play a man in the grip of an obsession, it is probably better to turn to En Fare for Samfundet, where we can see him play a man in the grip of insanity. But while the stills may not give a balanced impression of the performance of the film’s star, they do – in conjuction with the screenplay – support some tentative conclusions about the film’s style.

Significance

Lydia does not loom particularly large in considerations of Psilander’s career. Of course, this is first and foremost because the film is lost, but there are other reasons as well. There are indications that Lydia was not initially intended as a vehicle for Psilander at all. Script #1 includes a typewritten list of characters on the second page, with actors’ names written in by hand. According to these annotations, Carlo Wieth was slated to play Fribert. The rest of the cast was also somewhat different, although the list has only question marks next to the roles of Lydia and Gudrun (the nice-girl fiancée Fribert dumps to pursue Lydia). Steinwalt was to have been played by Robert Schmidt, not Peter Nielsen; instead, Schmidt replaced Anton de Verdier in the role of Kurt. Turning Lydia into a Psilander vehicle may have been a response to the worsening economic conditions brought on by World War 1.

During World War 1, Nordisk kept production high under the assumption that even though the war suppressed demand and many export markets became inaccessible, the completed films would remain assets to the company, ready to be marketed once the war ended and international trade resumed. Psilander films, in particular, were felt to be such assets. In the company’s production register (NF XI, 11), the films’ titles are followed by the designation “(Psilander I)”, “(Psilander II)”, etc. In 1916, only Psilander’s films are highlighted in this way, but in 1915, similar parentheses are added to the titles of a couple of other prominent stars (Gunnar Tolnæs, Clara Wieth). Nordisk released the films slowly in order to avoid flooding the market. Even in Denmark, where the films usually appeared first, the last Psilander film reached the cinemas only in July 1920, more than three years after Psilander’s death and nearly four years after the end of shooting.

Production dates may thus differ considerably from the time of a film’s premiere. For Danish silent films, the year of production can be found in Marguerite Engberg’s index Den danske stumfilm 1903–1930. For films made by Nordisk, the company’s surviving records enable us to establish the exact dates of production. Particularly important here is the production register. It lists film titles, names of directors, beginning and end of production, length, genre (comedy or drama), and other information. Here, we can see that Lydia was shot from 24 March to 17 April 1916 (NF XI, 11, pp. 28–29). It did not appear in Danish cinemas until 9 April 1918. The degree to which an unreleased film like Lydia was considered a marketable asset is suggested by the company’s poster order book, which indicates that an order for 500 copies of the film’s poster was placed on 14 July 1916, almost two years before the film’s eventual release (NF XI, 30, p. 6).

But by the time the film reached theaters, Psilander had already been dead for more than a year. This delayed release meant that the film went unmentioned in any of the numerous publications celebrating Psilander that were published in the wake of his death. When it came out, the film only received brief, if relatively positive, notices in the Copenhagen papers. The anonymous reviewer at Politiken writes: “The most compelling chapters of the novel are reborn in the film, transposed into moving images of a not inconsiderable effectiveness, even if the scenes set within the theater in this production are by no means the best” (10 April 1918). This is both saddening and reassuring, since the theater scenes (both the performances and the fire) are perhaps the ones that arouse most curiosity about what has been lost.

As previously mentioned, a handwritten note in the shooting script next to the scene of Lydia’s first performance mentions “Mrs. Walbom” (Script #2, [p. 8]). Emilie Walbom (1858-1932) was a ballet dancer whose career lasted more than six decades; she was also a choreographer and director, adapting ballets by Pepita and Fokine for the Danish stage, and she ran her own dance academy. The presence of her name in the shooting script suggests that she provided the choreography, the direction, and probably also the dancers for the two scenes where Lydia performs, and having the film would have been a precious record of her work.

The only trace of the fire scene is a brief description in the poster order book, since 300 copies of a double-size poster were also ordered, showing “Theater fire. Panic on the stairs. Vignette: Psilander in the grille box or panic in front of the iron curtain” (NF XI, 30, p. 6). The company’s poster inventory ledgers contain a similar description, but makes clear that the image of Psilander in the box was chosen for the vignette (NF XI, 29, vol. 5, p. 8).

Another intriguing aspect of the film that our paper sources do not allow us to grasp is how the moral ambiguity of the main characters played out on the screen. Was Gudrun presented as insipid, and Fribert’s infatuation with Lydia an understandable response to her powerful sexuality? Or was Gudrun allowed to be delightful and charming, making Fribert’s spurning of her seem senseless and shameful? Was Lydia played as a scheming femme fatale, or a victim? Would we grieve at Fribert’s tragic end, as the souvenir programme booklet suggests?

Even if these questions must remain unanswered, our sources do allow us to say quite a bit about Lydia. The screenplay allows us to get a good sense of the details of the story, and the intertitle list, the programme booklet, and the stills allow us to determine that the finished film did in fact conform quite closely to the screenplay. These materials also strongly suggest that Lydia used the tableau aesthetic we find in extant films made at the same time. Some of the other sources we have looked at give us an understanding of how a film like Lydia fit into to Nordisk’s business strategy. The novel not only yielded a fictional but intriguing pen-portrait of Psilander, examining it and reviews of it also allows us to say something about the place of Lydia in Dreyer’s career. While the script has his name on it, there is little to suggest that he had anything personal invested in the story. Cavling was a friend of his, and we may speculate that he just wanted to put some film company money in Cavling’s pocket by getting Nordisk to buy the rights for the novel; but it is also possible that he regarded Cavling’s books – described by contemporary reviewers as packed with excitement – as eminently suitable for Nordisk’s filming needs. Dreyer’s adaptation is certainly competent, smoothing the narrative and getting rid of some of the contrivances of Cavling’s novel. And in making the changes described, making the character of Fribert more sympathetic, Dreyer made the story more suitable as a star vehicle, allowing the lead role to be taken by Valdemar Psilander, the most fashionable actor of his day.

BY: CASPER TYBJERG / LEKTOR / INSTITUT FOR MEDIER, ERKENDELSE OG FORMIDLING / KØBENHAVNS UNIVERSITET

Notes

1. Script #1 has no page numbers, whereas the typed right-hand pages of Script #2 are numbered; still, in both cases, I shall use the page numbers generated automatically by the Issuu digital reader for reference, putting them in brackets to indicate that they are not present in the document.

References

Bordwell, David (1985). Narration in the Fiction Film. London, Methuen.

Bordwell, David (2010). "Nordisk and the Tableau Aesthetic". Available from http://www.davidbordwell.net/essays/nordisk.php#_edn15 [accessed 17 November 2016].Bramsen, Bo (1983). Politikens historie set indefra 1884-1984: en scrapbog. 2 vols. Copenhagen, Politikens Forlag.

Brewster, Ben, and Lea Jacobs (1997). Theatre to Cinema: Stage Pictorialism and Early Film. New York, Oxford University Press.

Cavling, Viggo (1914). Lydia. Copenhagen, V. Pios Boghandel – Povl Branner.

Christiansen, Svend (1975). Klassisk skuespilkunst. Stabile konventioner i skuespilkunsten 1700-1900. Copenhagen, Akademisk Forlag.

Drum, Dale D., and Jean Drum (2000). My Only Great Passion: The Life and Films of Carl Th. Dreyer. Scarecrow filmmakers series; no. 68. Lanham, Md., Scarecrow Press.

Nielsen, Jan (1997). "Carl Th. Dreyer – his very first filmscript." Aura vol. 4 (2-3): 102-107.

Nielsen, Jan (2003). A/S Filmfabriken Danmark: SRH/Filmfabriken Danmarks historie og produktion. Copenhagen, Multivers.Prawer, S. S. (2005). Between Two Worlds: The Jewish presence in German and Austrian Film, 1910-1933. New York, Berghahn Books.

Sandberg, Mark (2001). "Pocket Movies: Souvenir Cinema Programmes and the Danish Silent Cinema." Film History vol. 13 (1): 6-22.

Schröder, Stephan Michael (2006). "Scriptwriting for Nordisk 1906-1918." In Lisbeth Richter Larsen and Dan Nissen (ed.): 100 Years of Nordisk Film, 96-113. Copenhagen, DFI.

Schröder, Stephan Michael (2010). "The Script Consultant". DFI. Available from http://english.carlthdreyer.dk/AboutDreyer/Biography/The-Script-Consultant.aspx [accessed 18 November 2016].

Suggested citation

Tybjerg, Casper (2017): Psilander, Dreyer, and Lydia: A Documentary Study of a Lost Film. Kosmorama #267 (www.kosmorama.org).

Watch the films mentioned at 'Stumfilm.dk':