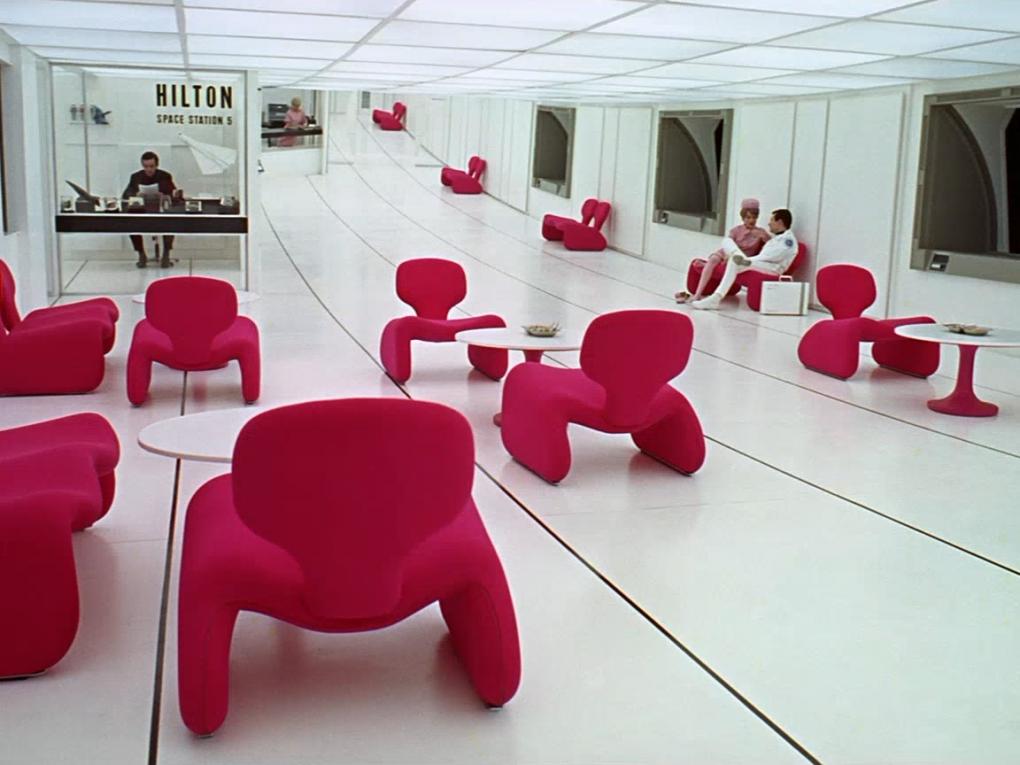

Design elements in film images exist to create a believable world in which action and art can unfold. Sometimes the task is to create a realistic depiction of the world as we know it. At other times, the designer invents original visual universes and story worlds where our eyes meet spaces and imagery that we have never seen before. Production design can take on many shapes and forms. In this special issue of Kosmorama we foreground production design rather than leaving it in its more traditional background position through a series of articles and essays on the subject.

The scholarly literature on production design outlines how production design can be marked by different degrees of ‘design intensity’, from being mostly invisible to creating remarkable sets that are crucial for the story (e.g. Affron and Affron 1995). Writing about the importance of film sets, David Bordwell and Kristin Thompson stress how production design is not only “a container for human events” but can also be a part of the narrative action (Bordwell and Thompson 2010: 121). As analyzed by Jakob Ion Wille and Jane Barnwell in this issue, there have been many different approaches to production design during the course of film history, and the digital media landscape presents more opportunities for thinking about design, visual storytelling and story worlds than ever before.

Film scholar C. S. Tashiro has argued that production designers should be regarded as mediators between the real world and the story world. As he puts it, reality needs to be shaped “to fictional ends” and “[T]he production designer sits at this conjunction between the world outside the story and the story’s needs” (Tashiro 1998: 4). In the narrowest interpretation of production design, the designer plans, creates, builds and dresses sets for film and television fiction. In the broadest sense, it is about the total design of imaginary worlds for multiplatform productions.

As head of the art department, the production designer works closely with a team of other specialized designers. Depending on the nature of the production these can, for instance, be art directors, illustrators, model builders, set designers, prop masters, story boarders, set dressers, previsualization artists and graphic designers. The work processes vary greatly from production to production, and the tasks of the production designer thus range across small and larger productions or in different national frameworks. However, the purpose of the production designer is always – across the many different tasks – to create what Lucy Fischer has called “an overall pictoral ‘vision‘for the work” in collaboration with the director, the cinematographer and others (Fischer 2015: 2). In this issue, Fischer presents examples of how this happens when the contemporary horror film draws on inspirations from Art Nouveau.

Traditionally, the production designer receives a screenplay and develops the visual concept based on the agreed upon cinematic style during the pre-production phase. As modern filmmaking has become increasingly dependent on computer generated images, the post-production phase also requires the work of the production designer. The stages of conception and execution are becoming ever more blurred (Maras 2009: 179) with different parts of the production blending together in the digital ecology (Millard 2014). This calls for involving the production designer in new ways. One example of such a process is Steven Spielberg’s blockbuster Minority Report (2002), discussed by the film’s production designer Alex McDowell in this special issue. To McDowell the traditional industrial mode of film production developing in linear fashion from script via pre-production to production and subsequent post-production is quite simply an anachronism best done away with. Modern film production design is holistic, non-linear and the idea of the author is completely dead.

However, the process of involving production designers at the early stages of development is also beneficial for less CGI-based kinds of storytelling, as recently analysed in a Danish context using the collaboration between showrunner Maya Ilsøe and production designer Mia Stensgaard on the television drama series Arvingerne/The Legacy (2014-2017) as an example (Redvall and Sabroe 2016; Wille and Waade 2016). Recently, the award-winning work of Danish production designer Jette Lehmann on the low-budget film Forældre/Parents (2016) beautifully showed how production design not only has an important part to play in major Hollywood productions or high-end television drama, but is also essential for telling original stories on a completely different scale.

In animation films and computer games, production design is highly regarded since it is fundamental to the very nature of creating story worlds beyond what we know from real life. In his by now classic work on convergence in media culture, Henry Jenkins exemplifies how the rest of the audiovisual sector might gradually be catching up with this understanding of production design and storytelling as completely intertwined. Jenkins illustrates the converging developments in the media landscape through the story of a screenwriter who used to focus on pitching the story when presenting new projects, based on the conviction that a good story is the basis of any good movie. Later in his career, the screenwriter pitched his characters, since good characters can inspire multiple storylines. But now, the screenwriter pitches story worlds, since a good fictional world will inspire multiple characters and stories and can be used on several platforms (Jenkins 2006: 114) – and this is often what is needed in the current media landscape.

As the articles and essays in this issue explore from different angles, a nuanced understanding of production design and the design process is valuable for thinking about the current state of film and television, animation and games. Needless to say, this understanding should also be part of how filmmaking is taught, which is partly what Morten Melgaard argues in his essay on teaching how to work artistically with lighting in filmmaking processes. Accordingly, it seems counterproductive and short-sighted that The Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts, School of Design recently decided to shut down the teaching of production designers for financial reasons. The decision comes at a point in time when production design is becoming more crucial to the entire filmmaking process than ever before. As argued by the Principal of the National Film School of Denmark, Vinca Wiedemann, this decision runs the risk of leading to ‘cinematic poverty’ in Danish filmmaking (in Marquard 2016).

The National Film School has for many years had an established collaboration with the production designers from the School of Design, for instance as part of the so-called TV-term where producers and screenwriters from the film school spend one term developing a potential new TV series together with the production designers (Redvall 2016). When taking on the post of Principal in 2014, Wiedemann highlighted screenwriting and production design as the two main elements to strengthen in the film school framework (in Lindberg 2014), and she is currently investigating whether it might be possible to include the education of production designers at the film school. How this will play out, remains to be seen – but the absence of production design training from film education in Denmark hardly seems conducive to a flourishing a national film culture.

Eva Novrup Redvall & Jakob Ion Wille are guest editors of this issue of Kosmorama.

References

Affron, Charles and Affron, Mirella J. (1995). Sets in Motion: Art Direction and Film Narrative, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press.

Bordwell, David and Thompson, Kristin (2010). Film Art: An Introduction, 9th ed., New York: McGraw-Hill.

Fischer, Lucy (2015). Art Direction and Production Design, London: I.B. Tauris & Co. Ltd.

Jenkins, Henry (2006). Convergence Culture. Where Old an New Media Collide, New York: New York University Press

Lindberg, Kristian (2014). ‘Filmskolens nye rector: “Der er for lidt af det danske og for lidt kvalitet”.’In: Berlingske.dk, 1. august. https://www.b.dk/kultur/filmskolens-nye-rektor-der-er-for-lidt-af-det-danske-og-for-lidt-kvalitet

Marquard, Frida (2016). ‘Production design-uddannelsen lukker.’ In: EKKOfilm.dk, 26 October. http://www.ekkofilm.dk/artikler/production-design-uddannelsen-lukker/

Maras, Steven (2009), Screenwriting: History, Theory and Practice, London: Wallflower Press.

Millard, Kathryn (2014), Screenwriting in a Digital Era, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Redvall, Eva N. (2015). ‘Craft, creativity, collaboration, and connections: Educating talent for Danish television drama series.’ In Miranda Banks, Bridget Conor and Vicki Mayer (eds): Production Studies, The Sequel! London: Routledge.

Redvall, Eva N. and Iben A. Sabroe (2016). ‘Production design as a storytelling tool in the writing of Danish TV drama series The Legacy.’ Journal of Screenwriting 7(3): 299-317,

Tashiro, C. S. (1998), Pretty Pictures: Production Design and The History of Film, Austin: University of Texas Press.

Wille, Jakob I. and Anne M. Waade. 2016. Production Design and Location in the Danish television drama series Arvingerne, Kosmorama #263.

Suggested citation

Wille, Jakob Ion & Redvall, Eva Novrup (2017): Production design and the creation of story worlds – Introduction. Kosmorama #268 (www.kosmorama.org).

JAKOB ION WILLE & EVA NOVRUP REDVALL