After trashing Vilgot Sjöman’s film I am Curious – Yellow (Jag är nyfiken – gul, 1967) upon its U.S. release in 1969, American film critic Roger Ebert concluded his review by stating: ”The one interesting aspect is that the hero succeeds in doing something no other man has ever been able to do. He makes love detumescently. I say the hell with the movie; let’s have his secret” (Ebert 1969). This statement testifies to what might be perceived as the film’s inauthenticity: although proclaiming to portray sexuality honestly and straightforwardly, it still does not offer that ostensibly ultimate proof of the man’s attraction to the woman and of their actual lovemaking in the film. Now, since the actors in the film were not, for instance, live show artists (commonly used as performers in early Swedish pornographic film), the intercourse scenes in I am Curious – Yellow were, for all their supposed candidness, simulated. The absence of the tumescent penis in the film is thus a result of this simulation, and, in its extension, an evidence of its inauthenticity.

The body communicates sexual attraction and arousal with several complex nervous reactions in the body. This involves increased heart rate, swelling of the genital glands and erectile tissue in both men and women, contracted nipples, and, in women, lubrication (Lundberg 2010). These bodily expressions have been observed in experiments conducted by early sex researchers such as Alfred C. Kinsey and William H. Masters and Virginia Johnson (Kinsey, Pomeroy, Martin 1948; Kinsey 1953; Masters & Johnson 1966), but they are more or less reflex reactions – we cannot will them. We may be able to conjure these expressions through bringing forth in our minds sexual fantasies or memories but, unlike a smile or a scowl, a defensive pose or even a startled jump, we cannot act lubrication or erection.

The main objective of this article is to discuss the body language of the penis, and to analyze the extent to which this language may or may not work as part of a matrix of meanings in the moving image. A matrix of meanings refers here to the different ways in which the penis could be seen to communicate beyond the common interpretation of yes or no to sexual intercourse, here in the context of reading moving images. Since we interpret body language within the social context of the real world, we understand it quite similarly when reading films and television series. Therefore, representations of body language in the moving image function in transparent and obvious ways to the viewer. However, the particular aspect of the (non-)erect penis as body language in focus in this article is, due to generic conventions and regulations, not allowed to be shown in full and is thus limited in its means to communicate diversity in sexual desires, emotions, and actions and the potential responses in others.

Although the immediacy of bodily signs of sexual arousal would seem to make them convincing as authentic physical communication, these signs are, in most forms of popular culture, regarded obscene – either by law or by self-censorship – and thus avoided. With the exception of pornography and certain instances of art or independent cinema (such as Romance (Catherine Breillat, 1999); The Brown Bunny (Vincent Gallo, 2003); or Antichrist (Lars von Trier, 2009)) we are hardly ever shown erect penises or close-ups of lubricated, glistening labia.

The exclusion of the penis, in particular the tumescent one, from mainstream moving images has been understood in different ways. One of the most notable studies of

representations of the penis is Peter Lehman’s classic Running Scared: Masculinity and the Representation of the Male Body from 1993 with a new edition in 2007. Lehman argues that a gap exists between the mythological phallus and the actual penis and consequently, in order to retain the ”awe and mystique” of the phallus, the penis must remain hidden. Furthermore, Lehman claims, the representation of the penis confronts men with two threats in their general identity constructions as masculine: one having to do with women’s ability to compare and pass judgement and the other with homophobia (Lehman 2007: 236).

Lehman’s study relies to a large extent on psychoanalysis for its interpretation of various representations of the male body. Also, there is a recurring emphasis on size, whereas the focus in this article is the dichotomy of the erect and non-erect penis. Although it is reasonable to see some form of anxiety at work in representations of the penis, the fact that this anxiety has to do with a gap between penis and phallus remains to be demonstrated. The problem with representing the erect penis – in comparison with for instance full frontal female nudity – is its overt association with sexual activity. It cannot really be compared to nudity as such but rather with the beaver shot or close-up of female genitalia. The erect penis is unequivocally obscene. As pointed out by other scholars, the less visible signs of arousal in the female body compared with the male body signify a representational problem. Linda Williams has analyzed the money shot in pornography – that shows ejaculation – in terms of a visible evidence of pleasure having taken place. She also looked at pornographic film in terms of ”scientia sexualis” that is, a quest for knowledge about in particular female pleasure (Williams 1999). However, if in pornography the visibility of male arousal and sexual release is something that is cherished, in mainstream film, the same visibility is problematic.

Consequently, although anxieties in relation to representations of the penis certainly exist, one of the reasons for it being censored and avoided is – in my opinion – practical. The erect penis is both difficult to control and signals sex in a very visceral manner. This latter feature is highly problematic since human societies usually place limits on the display of genitals and copulation (Grodal 2009: 67). The anxieties pertaining to representations of the (erect) penis could very well relate to size and homophobia, but much of this anxiety seems to connect to its visual outspokenness and an ambivalent relationship to sexuality in contemporary Western societies.

Additionally, the body language of the penis – when explicit – has a tendency to evoke an embodied response in the spectator, at least in hardcore imagery (see e.g. Janssen, Carpenter, Graham 2003). In the following, I shall through a discussion of both the physiological and cultural side of tumescence demonstrate the dichotomic representation of the penis and, by drawing on both mainstream and pornographic film discuss the penis’ ability to speak, how the penis may – and may be allowed to – speak. This approach will help demonstrate the possible multiple meanings through which the (non-)erect penis could actually be read, as well as suggest what the penis communicates in those instances where it is allowed to speak.

Tumescence and detumescence as body language

Body language in the moving image can be regarded as a set of bodily expressions originally defined in ”real life,” outside of the media. Various emotions are thus expressed not only facially, but through posture, gestures, and movement. In real life, some of these physical expressions are, although hard to control, more or less voluntary: we mean to raise a fist when we are angry, or to lean forward when making a point. Others are involuntary, like trembling with abstinence or startling when we are surprised. In either case, body language is a useful tool in acting, not least to represent ambiguous feelings or ambivalence (the words say one thing, the body says another), but also to reinforce the sense or atmosphere of various situations or to communicate emotions without dialogue.

As one of the most obvious examples of body language in real life, the erect or non-erect penis seems to speak of willingness or unwillingness, that is arousal or non-arousal, and even opposite feelings such as disgust or indifference versus need, want, desire, or attraction. In a sexual situation, it can say yes or it can say no. As a sign, then, the penis might be reduced to being regarded as either “on” or “off.” This, however, is a very simplified way of looking at the body language of the penis.

Physiologically, erections do not necessarily have to do with willingness to engage in sexual activity. Since they are initiated by the parasympathetic division of the autonomic nervous system (Lundberg 2010), erections are not the outcome of muscles flexed at will or by a conscious decision of the mind. This lack of mental control actually makes the erection quite a fragile component of the social construction of masculinity, which emphasizes (sexual) control, “knowledge,” and agency (e.g. Potts 2000). This fragility is reinforced physiologically by an inhibitory system, which is activated for instance by stress, that interrupts the erection (Lundberg 2010). So, if an erection does not always signify a “yes” to sexual intercourse, neither does a flaccid penis necessarily mean a no, at least not a deliberate no.

Furthermore, the meaning can be situational: tumescence may simply signal yes in a situation where such a yes is wanted and desired by both or all parties. In another situation, where such a yes is unwanted by the opposite party, it might signal a threat. By some radical feminists, the erect penis has been analyzed as a potential weapon, contributing to patriarchy’s subjection of women through the threat of rape. In Susan Brownmiller’s feminist classic Against Our Will: Men, Women, and Rapefrom 1975, the invention of rape, for instance, is thought of as a discovery that enables the penis to be used as a weapon (Brownmiller 1975). Finally, the “yes” of the penis might be unwanted by the man in question himself, and thus also function as a threat, to himself in this case, of embarrassment. Correspondingly, the flaccid penis may signal no in a situation in which such no is wanted or expected, for instance, in non-sexual situations like a public locker room at a swimming pool. But it may also mean an involuntary no in a sexual situation where penile penetration is made impossible by the non-existent erection: a no that more or less disappoints both parties and even can be a blow to both male and female self-esteem. Erectile dysfunction as defined by a medical discourse is seen to have psychological or physiological causes, but it is also often said to create low self-esteem and a sense of loss of manliness (Elmerstig 2012). This has to do with how penile-vaginal penetration is regarded as “proper” sex within dominant discourse, but the centrality of erection in the social construction of masculinity becomes even more evident when considering the older and still colloquially used term for erectile dysfunction, impotence. The word impotence functions metaphorically to underline powerlessness, uselessness, weakness, and inability. Accordingly, a man’s ability to have an erection becomes not only a part of his sexuality but reflects back on his personality as well. Social constructionists have critiqued this notion of erectile dysfunction and, in its extension, the discursive fixation on erection and penetration, claiming that it is a reductive view of sexuality, that it constructs a view of masculinity as a machine that can be “fixed” (with proper medication; i.e. it reinforces the “medicalization of sexuality” [Tiefer 2004]), that it upholds a phallocentric worldview, and patriarchal hegemony (see e.g. Potts 2000; Tiefer 2004).

The body language of the penis can thus be said to come out of a simple “on” or “off” rooted in these bodily reactions. Nonetheless, due both to its physiological functions and to cultural and social understandings of tumescence and detumescence, the penis is actually very eloquent and can, depending on the situation, communicate threat, aggression, embarrassment, disappointment, authenticity or inauthenticity, relaxation, and eagerness. The tumescent penis spans from dangerous to fragile, depending on context and, also, to some extent, the viewer. Gender, sexuality, past experiences, age, even race and ethnicity (as in the example with the Lasse Braun film White Fantasies described below), may influence how the viewer understands the penis.

In any case, this potential body language is, with a few exceptions, excluded from mainstream or non-pornographic representation. The distinction between softcore and hardcore draws the line at erections and close-ups of genitalia during intercourse. Albeit not as frequently as female nudity, full frontal male nudity may very well be shown in films and TV-series, of the more R-oriented kind, but none of these males, even if in a sexual situation, show any indication of physical arousal, in particular not in the U.S. Thus, the penis is not allowed to “speak,” because even when it is flaccid, the detumescence is not charged with any meaning since its opposite is not allowed to be shown. This is the case even in quite sexually explicit media representations such as the HBO series Game of Thrones (2011-). In pornography, on the other hand, tumescence is not only allowed but expected.

Expected erections

In pornography, the erection is central to the extent that camera level and camera angles foreground it, sometimes at the expense of the male performer’s head and face. Even in girl-on-girl scenes, its absence requires a substitute or a stand-in in the form of a dildo or vibrator. You may see a flaccid penis in the beginning of a scene – especially in porn from the 1970s and 1980s – but in that case, the point of showing it is to illustrate the gradual development of physical arousal.

One of the reasons why the erection – and close-ups of female genitalia – is central in porn is pornography’s specific intention to evoke sexual arousal in the viewer. The viewer’s body responds to the visceral images of sexual activity and genitalia. Because pornographic clips provoke a reliable reaction of physical arousal in the spectator, they are, in fact, frequently used in physiological sex research (e.g. Janssen, Carpenter, Graham 2003).

Before the release of Viagra in 1998, being a male porn star depended primarily on the extent to which the performer could acquire and maintain an erection in front of camera and crew. A chapter in Susan Faludi’s Stiffed: The Betrayal of the American Man, (”Waiting for Wood”) actually dealt with a porn shoot, while the ”wood” spoken of in the chapter heading referred to the tumescent penis. Faludi’s analysis suggests that modern society has made men dependent on the only muscle that they cannot flex (Faludi 1999). Faludi’s book came out at roughly the same time as Viagra was approved and released on the market, changing the conditions not only for men who experienced erectile dysfunction but also for porn production.

Since the opposite of tumescence is not really an option, at least when utilized in porn, one could argue that not only in non-pornographic moving images is the penis forbidden to speak. If meaning is somehow provided through difference, and the penis cannot communicate unarousal, uninterest, or repulsion, it cannot communicate attraction and arousal either. The erection is already a given, taken for granted within genre expectations. Even so, I would contend, there is more possibility for expressions of the penis in porn, not only because a constant yes says more than a constant no, but also because of the particularity involved in, for instance, expressing mounting arousal.

In two 8mm pornographic films by Lasse Braun from the late 1960s and early 1970s, the flaccid penis is used to communicate a ”no” from the man in question. Since the films have no dialogue, the use of detumescence is a way of utilizing the body language of the penis to communicate a narrative of emotions to the audience. Both these films were censored by the Swedish National Board of Film Censors because they were violent: one was cut by one quarter and the other disallowed for public screening (Larsson, submitted). Both of them are approximately 10 minutes long.

White Fantasies or Black Power was produced in 1969 in Trinidad. Here, two black women are having sex in a garden while a white man sits on the porch and watches distractedly before he joins them. After a while, however, two black men – in Black Power T-shirts – are disclosed by the camera as spying on them, and soon they attack the threesome, hit the women (one so badly that she falls unconscious) and carry off the man. They tie him up at the porch and proceed to rape the conscious woman. While this quite violent rape is going on, shots showing the white man watching are intercut. One of these shots of the white man show his genital area, seemingly to emphasize the flaccid penis. Although one of the titles of the film is White Fantasies, through the shot of the flaccid penis, the film seems to underline that the man is not aroused by watching the rape.

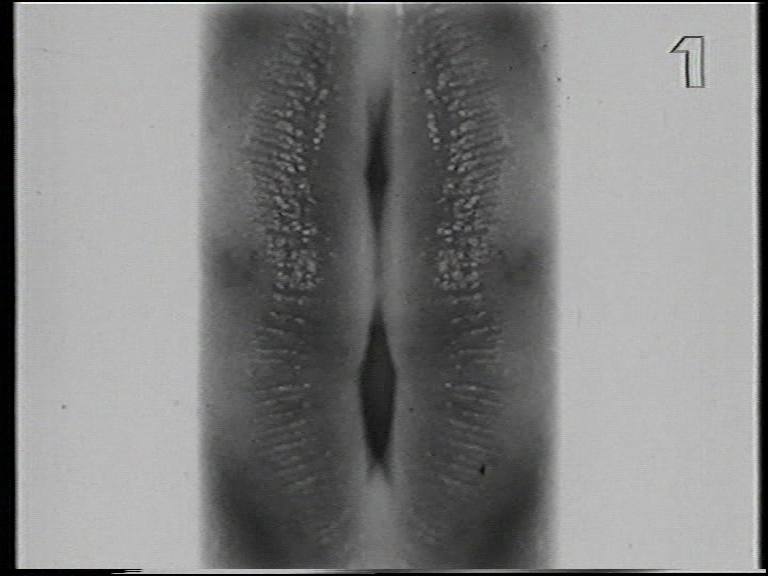

On the other hand, in Cerimony from 1971, the flaccid penis is also shown. Cerimony was banned by the National Board of Film Censors because of its disturbing violence, featuring the rape of one man by six women, dressed up as some kind of witches. Now, the common understanding is that men cannot be raped (at least not by women), partly because we understand rape as being penetrated against one’s will but also because the presence of an erection would put the unwillingness of the man into question. In 1970s porn films, rape scenarios are rare but they do exist, even though almost all of them were disallowed or cut by the National Board of Film Censors. In the majority of these scenarios, it is a woman who is raped by one or more men. If a film portrayed violence and coerced sex throughout, it would usually be disallowed. However, in some cases the initial resistance of the women would, through the course of the film, turn into acquiescence. In these films, most commonly only the first few minutes which showed the woman struggling – saying ”no” with her body language – would be cut out by the Board, whereas the part in which the woman not only submits to but actually enjoys the sex would be retained (Larsson, submitted). In Cerimony, the male no turning into acquiescence is visually depicted through a close-up of the penis in profile, unrealistically quickly rising into an erection. However, in this case, the entire film was disallowed by the Board.

In both these films, the body language of the penis appears to be utilized to suggest specific meanings using visual means, especially since the films are silent. In the first case, it is the unarousal at the scene taking place in front of the man. In the second case, it is actually a ”no” becoming a ”yes” in an almost comical rendition. As such, in both these instances, the penis is made to speak in a very literal manner.

The symbolic body language of the penis

While some pornographic films allow the penis to speak beyond common conventions, some mainstream (art) films also make attempts at this, suggesting other meanings than merely sexual. In Ingmar Bergman’s Persona from 1966, there is an unexplained penis among several other unexplained images in the prologue to the film.

The fragmentation of images shown calls for interpretation, and thus, the penis – like the other images – is to be understood as symbolic. After only 39-40 seconds, an erect penis appears very briefly, almost subliminally. This shot, so brief that some spectators most likely missed it during the first screening, is included in the introduction to the film: some six minutes of highly self-referential images of a film projector being lit and beginning to roll the film strip, an animated film, someone’s hands, clips from the silent film produced for and featuring in Bergman’s own Prison (Fängelse, 1949), a spider, a lamb being slaughtered, a nail being driven through a hand, before concluding with the scene with the boy and the female faces of Liv Ullman and Bibi Andersson.

The penis is shown very early in this first sequence, which contains images that can be related to an idea of film as film: the materiality of the film strip, the projector, the light, and the images that are fed through the projector. As Maaret Koskinen points out in her dissertation on Bergman, several scholars have described the prologue to Persona as a kind of birth or beginning in several ways: Biologically, but also in a filmic manner, a ”let there be light” that continues with the strip of film running through the projector. Furthermore, it can be read as a symbolic rendition of cinema’s development, with the rudimentary animated figure, followed by ”realistic” hands, but also referencing Bergman’s own film production: Prison, The Seventh Seal (Det sjunde inseglet, 1957), Through a Glass Darkly (Såsom i en spegel, 1961), and ending with the boy from The Silence(Tystnaden, 1963) (Koskinen 1993, 226-228). Koskinen concludes by stating that the prologue can thus be regarded as showing the audience the artistic conception as it is produced: a thumbing through old themes until ending with the blended image of the two women’s faces and then, during the credits, ”breaking out into a kind of chaotic ’brainstorm’” (Koskinen 1993, 228, my transl.). But the prologue is simultaneously regarded as a visual attack on the spectator.

So, if this is indeed a procreative moment, conceiving and birthing the film, the erect penis has a very literal meaning in this context. As such, it actually has a counterpart which is a vulva-like image that shows up right after Bibi Andersson’s name in the credits. If this is supposed to be the female genitalia, it is a rather stylized and ambiguous image, especially in comparison with the frankness of the shot of the penis. (This does appear like a cop-out, given that it looks like a double reflection of either the upper or the bottom lip, filmed to appear vertically.)

At the same time the image of the erect penis also seems to reference the projection into the world of the male body. This is analogous to how the projector projects the film, which is phallic in the sense that it contains an idea of virility and masculinity, of stretching out for something and reaching. Moreover, since the shot is so brief, it plays like a joke on censorship and the audience: Did you really see it? Was that what I thought it was?

When Bergman passed away in 2007, the blog ”Film Ick” published an entry on this shot, comparing it with the shot inserted at the end of David Fincher’s Fight Club (1999). The Blogger, Brandon, wrote: ”When the 'flash cut' [in Fight Club] comes, not only is it obvious and painfully laboured, it's also a limp penis. How appropriate. [--] That says it all, really: Bergman offers the penis up, unannounced, but part of an incredible sequence; Fincher promises it, then never delivers” (Film Ick, 2007). While the blog entry received quite negative comment response, it does illustrate the significance of images of the penis in various stages of tumescence. An erect penis is “the real thing,” a non-erect (or “limp”) penis is appropriate for a film director whom the blogger suggests is overrated and in fact, maybe even “limp” or inauthentic himself.

Inhibited body language

While attempts have been made at making the penis speak in both porn film and mainstream (art) film, the same applies to the Swedish pornographic press. Within Swedish pornographic press, erection was the “last barrier” to be broken down in 1967, most likely by Berth Milton Sr. in the magazine Private (Arnberg 2010: 200). However, since pornography was still illegal in Sweden in 1967, pornographic magazines showed erection at the risk of being indicted and convicted for “sårande av tukt och sedlighet” (“offensive of morals and social standards”) in accordance with the obscenity law. Although obscenity law was part of the penal code, the Cinema Act that regulated film censorship contained a clause that referred to “general law” which meant that the obscenity clause applied also to films that were to be screened in public. At the time when Berth Milton published images of erections and I am Curious – Yellow was released, the obscenity clause as well as film censorship was under inquiry by two public commissions (SOU 1969:38 and SOU 1969:14). In 1969 it was decided to remove the obscenity clause, which happened in 1971. Thus, during these years in Sweden and the Western world, definitions of obscenity were the object of much interpretation and the limits as to what could be shown were rapidly changing. This is evidenced by the censorship board discussions on the sex education films From the Language of Love (Ur kärlekens språk, Torgny Wickman, 1969) and More from the Language of Love (Mera ur kärlekens språk, Torgny Wickman, 1970) (Björklund 2012).

In both of the Curious films (Yellow and Blue) there is a documentarist inception. The films play self-reflectively on the relation between fiction and reality, through for instance the use of the actors’ first names as the names of the characters – Lena Nyman plays Lena, Börje Ahlstedt plays Börje, Vilgot Sjöman plays Vilgot – but also through a kind of frame narrative, which deals with Vilgot and Lena making a film.

According to Anders Åberg, a source of inspiration for the Curious films was Jean Rouch and his documentary form cinema vérité (Åberg 2001: 179). The intentions behind the Curious films were many, but they involved making radical and provocative statements – politically as well as sexually – and breaking down not least Sjöman’s own taboos about what (not) to show in sex scenes. He wanted none of the “hiding strategically behind sheets” found in Hollywood films, or the body stockings used for Nyman in his own controversial 491 (1964) (Sjöman 1998). Instead, Sjöman wanted candid, frank, and honest depictions of sex which consequently were conscious provocations of the censorship regulations. Interestingly, Swedish anti-obscenity lawyer Leif Silbersky claimed to have taken the whole court to the movies to see I am Curious – Yellow during an obscenity trial for some pornographic magazines, arguing that if this was allowed to be shown on screens, the still images in the magazines should be allowed as well (Silbersky & Nordmark, 1969).

In light of these ambitions to portray sex overtly, the missing erections kind of ring false: it is a flaw in the Curious project. Nonetheless, it may very well have been these missing erections and, thus, the missing speech by the penis, which made the films possible to be approved by the National Board of Film Censorship.

The limitations of body language

Instances of erect penises in mainstream cinema are extremely rare. In a recent Swedish film, Behind Blue Skies (Himlen är oskyldigt blå, Hannes Holm, 2010), a very brief shot in the beginning of the film shows an erection (actually, a realistic dildo functions as a “body double” [Hammerkrantz 2010]) in the foreground of the frame. Probably this has to do with the fact that the film takes place in the 1970s and by this brief shot, it refers to our conceptions of how the 1970s were with regards to sex. Nonetheless, since public display of genitals and sexual activities is generally forbidden in the real world, these displays are also usually shown in a restricted way in non-pornographic media representations. From the examples used in this article about the erect and non-erect penis, it would seem that although body language in the moving image may to a large extent be transparent, not all aspects of body language are covered. Furthermore, the examples demonstrate that in most cases, the restrictions placed on the showing of the male genitalia limit its possibilities to communicate. Since erection cannot be shown to communicate arousal, neither does a flaccid penis (like in I am curious – yellow or in Game of Thrones) indicate that the man in question is uninterested in sexual activity per se.

Conversely, the specific intent of pornography to elicit arousal in the viewer also limits the ways in which the penis can communicate. There is a bit more room for maneuver in porn, since detumescence is not strictly forbidden, but for the most part it is avoided. Nevertheless, as Grodal points out, “visual inspection elicits sexual excitement in the viewer in that such access represents partial acceptance of initiating a sexual relationship and functions as an emotional trigger. Humans and animals shop around and signal their attractiveness through the display of antlers, breasts, hips, penises, peacock tails, and the like” (Grodal 2009: 67). The visual display of genitals in pornography thus functions as a communicative tool on a more innate level, and, as the use of porn clips in physiological sex research shows, speaks to the body of the viewer, which responds in kind. This might also be an explanation as to why there is such a strict line drawn at the tumescent penis between non-pornographic and hardcore imagery. Regardless of variation in viewer responses – which do exist – this limitation (or potential) of the body language of the penis is quite ubiquitous.

BY: MARIAH LARSSON / RESEARCH FELLOW / DEPT. OF MEDIA AND COMMUNICATION, SECTION FOR CINEMA STUDIES / STOCKHOLM UNIVERSITY

References

Arnberg, Klara (2010) Motsättningarnas marknad: den pornografiska pressens kommersiella genombrott och regleringen av pornografi i Sverige 1950-1980, Lund: Sekel bokförlag

Björklund, Elisabet (2012) The most delicate subject: a history of sex education films in Sweden. Diss. Lund: Lund University

Brownmiller, Susan (1975) Against Our Will: Men, Women and Rape. New York: Simon & Schuster

Dworkin, Andrea (1981) Pornography: Men Possessing Women, London: Women’s Press

Dworkin, Andrea (1987) Intercourse, New York: Free Press

Ebert, Roger (1969) Review of I am Curious – Yellow, Chicago Sun-Times, 23 September

Elmerstig, Eva (2012) “Sexuella problem och sexuella dysfunktioner”, in Lars Plantin & Sven-Axel Månsson, Sexualitetsstudier, Stockholm: Liber

Faludi, Susan (1999) Stiffed: The Betrayal of the Modern Man, London: Chatto & Windus

Film Ick (2007) “Ingmar Bergman’s Big Hard Cock”, Film Ick http://filmick.blogspot.com/2007/07/ingmar-bergmans-big-hard-cock.html July 30 [accessed 19 February 2014]

Grodal, Torben (2009) Embodied Visions: Evolution, Emotion, Culture, and Film, Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press.

Hammerkrantz, Oskar, ”’Det är faktiskt en specialtillverkad löspenis’”, interview with Bill Skarsgård, Café 9/2010, http://cafe.se/det-ar-faktiskt-en-specialtillverkad-lospenis/ [accessed 22 August 2014]

Janssen, Erick, Deanna Carpenter, Cynthia A Graham (2003) “Selecting Films for Sex Research: Gender Differences in Erotic Film Preference”, Archives of Sexual Behavior, vol. 32, no. 3, p. 243–251

Kinsey, Alfred C., Wardell B. Pomeroy & Clyde E. Martin (1948), Sexual Behavior in the Human Male, Philadelphia: Saunders

Kinsey, Alfred C., Wardell B. Pomeroy & Clyde E. Martin (1953), Sexual Behavior in the Human Female, Philadelphia: Saunders

Koskinen, Maaret (1993) Spel och speglingar: en studie i Ingmar Bergmans filmiska estetik, Diss. Stockholm University

Larsson, Mariah (submitted) ”Lasse Braun, Rape Scenarios, and Swedish Censorship: A Case Study of Two 8mm Porn Films Featuring Rape”

Lehman. Peter (2007) Running Scared: Masculinity and the Representation of the Male Body (2nd ed) Detroit: Wayne State University Press

Lundberg, PO (2010) ”Sexualorganens anatomi och fysiologi”, in PO Lundberg & Lotta Löfgren-Mårtenson (eds), Sexologi (3rd ed), Stockholm: Liber, pp. 53-72

Masters, William H. & Virginia E Johnson (1966), Human Sexual Response, Boston: Little, Brown

Potts, Annie (2000), “’The Essence of the Hard On’: Hegemonic Masculinity and the Cultural Construction of ‘Erectile Dysfunction’”, Men and Masculinities, vol 3:85, pp. 85-103

Silbersky, Leif & Nordmark, Carlösten (1969) Såra tukt och sedlighet: en debattbok om pornografin, Stockholm: Prisma

Sjöman, Vilgot (1998), Mitt personregister. Urval 98, "-in i filmateljén", Stockholm: Natur och kultur

SOU 1969:14, Filmcensurutredningen (1969) Filmen – censur och ansvar: betänkande, Stockholm

SOU 1969:38, Kommittén för lagstiftningen om yttrande- och tryckfrihet (1969) Yttrandefrihetens gränser: sårande av tukt och sedlighet: brott mot trosfrid: betänkande, Stockholm

Tiefer, Leonore (2004), Sex is not a Natural Act and Other Essays, 2. ed. Boulder, Co: Westview Press

Williams, Linda (1999) Hard core: power, pleasure, and the “frenzy of the visible”, (expanded pbk. ed.) Berkeley: Univ. of California Press

Åberg, Anders (2001), Tabu: filmaren Vilgot Sjöman, Lund: Filmhäftet förlag

Kildeangivelse: Larsson, Mariah (2014): Making Love Detumescently: Some Preliminary Notes on the Body Language of the Penis. Kosmorama #258 (www.kosmorama.org)