David Bordwell’s assessment (1981, 171) that “Gertrud is the most problematic film of Dreyer’s career” summarises critical consensus that Dreyer’s last film is at best difficult, at worst intractable. The most frequently noted of its alleged ‘problems’ are: the conflict between a naturalistic domestic “melodrama” (Dictator 2024, 143) filmed in a non-naturalistic manner; spectatorial distancing through the complete absence of close-up shots; the virtual elimination of shot/reverse shots, filming entirely through strict frontality “like a series of tableaux vivants” (Burch 1974, 57); and a barely functioning dialogue, devoid of expressive modulation and delivered at rather than to the recipient. As Dreyer himself remarked, “They spoke past each other” (Trolle 1965, 99).1

Gertrud’s premier in Paris on 18th December 1964 was a well-publicised fiasco. Reviews were overwhelmingly negative: “a bouquet of spite and scorn such as this had never been flung at the most meretricious of Gallic Z-nudie movies” (Drum 2000, 263). Even the Danish ambassador to France who had hosted the premier scathingly criticised the “endless nonsense of the dialogue” in the press (Kristeligt Dagblad 19th December 1964).

There followed a brief positive re-evaluation amongst French cinéastes. In the February 1965 edition of Cahiers du cinéma, Chabrol, Téchiné, Godard, Rohmer and Rivette ranked the film amongst the top three releases of 1964. Subsequently, Truffaut (1980, 80) and Deleuze (1989, 178) were amongst French directors and theorists praising Gertrud. Elsewhere, the response remained muted or outright negative, even decades after its release: the only exception was Carney’s Speaking the Language of Desire (1989). Thomsen, for example, refers to the film’s “catastrophic lack of distance from the protagonist’s self-obsessed tirades” (1989, 42). Kau refers to Gertrud as a “a large tableau of a fossilised life” (1989, 378). Bordwell, in the much referenced The Films of C.T. Dreyer argues Gertrud is “contradictory, illegible and unconsumable … hovering on the brink of unintelligibility or vacuity” (1981, 65).

How to decipher a film that “… still offends perception” (Deleuze 1989, 41) decades after its release? This essay argues that, ironically, the answer lies in an intended criticism, describing Gertrud as a “two-hour study of sofas and pianos” (Kruuse 1964, 25). An essential entry point into the film’s significance is through examining the props deployed by Dreyer. His meticulous attention to the mise-en-scène engages with Henning Bendtsen’s cinematography to prioritise the props at the expense of the depiction of the protagonists. The selection of props and their positioning relative to the protagonists combined with Dreyer’s flattening of three-dimensional space create meaning that extends far beyond what can, for example, be gleaned from the film’s mostly tortured dialogue. This essay focuses on two props: the piano, depicted in most interior scenes; and the statue of Aphrodite/Venus, depicted in the two park scenes. Beyond their ‘activation’ and utilisation in key scenes, they are – despite visual absence – subtly referenced elsewhere in the diegesis. These two props are representative of the film’s aesthetic focus: there are numerous references to the fine arts, which considerably extend the spectator’s panorama and reference points beyond the bourgeois confines of the Kannings’ home, where Gertrud is largely filmed.

Sofer argues in The Stage Life of Props, “Props are not static symbols, but precision tools whose dramaturgical role in revising outmoded theatrical contracts with the audience has long been neglected” (2003, 3). Scholarship to date has, I argue, overlooked a detailed analysis of the use of props in Gertrud. Critical focus has instead been directed towards filming techniques around these props, where they are mentioned at all. Only the tapestry, rendered an effortless target for observation through spatial positioning and frequent reference through dialogue, has been repeatedly noted. Separately, significant works of Western art have been ignored or misquoted. Overlooking the props’ significance could be considered a tactic to support the more formalist evaluation of critics such as Thomsen and Bordwell. In contrast, I argue that evaluating the coding contained within the props allows for a reappraisal of the film. The outcome is an interpretation that is considerably more life-affirming than has until now been largely proposed.

Sources

Dreyer’s source for Gertrud was the eponymous drame by the Swedish playwright, Hjalmar Söderberg (1906). Dreyer elected plays as his preferred source, claiming that “novels shouldn’t be filmed, it’s too hard. I prefer to film theatre” (Sarris 1967, 16). He was at pains to highlight the fidelity of Gertrud to its source: the opening film credit identifies the film as “Hjalmar Söderberg’s Gertrud”: the subsequent description of the film as “A period piece from the turn of the century, reworked for film by Carl. Th. Dreyer.” (Fig, 1, right) deliberately designates the film as an image emanating from the past.

Dreyer followed Söderberg’s lengthy stage directions to the letter: running over 17 lines in the printed version (1921, 9), they are far more detailed, for example, than Ibsen’s in A Doll’s House (1879), or Strindberg’s in Miss Julie (1888), contemporaneous plays with comparable thematic and setting.

Dreyer meticulously assembled the props to be included “as if in preparation for a thesis” (Thomsen 1968, 15). Once the film crew had prepared the set, Dreyer together with Bendtsen removed all but the few props they considered essential. Dreyer commented in separate interviews that his intention was twofold: to ensure the actors “would eventually feel it was their sitting room they were living in. This is really important.” (Trolle 1965, 99); secondly, that “the personality of the actors (would be) reflected in all the details that surround them” (Parrain 1967, 12). The importance of the ‘mise-en-milieu’ has been considered again in more recent scholarship, with Mark Sandberg (2006, 24) highlighting how “throughout his career two notions dominate consistently: authenticity and inhabitation” and that (2006, 25) “…it was something in the performance process that mattered to Dreyer – the actor’s attachment to the set, not the spectator’s. The set was a catalyst for an inner performance transaction in the actor, one produced by his or her confidence in the possible inhabitability of a set.”

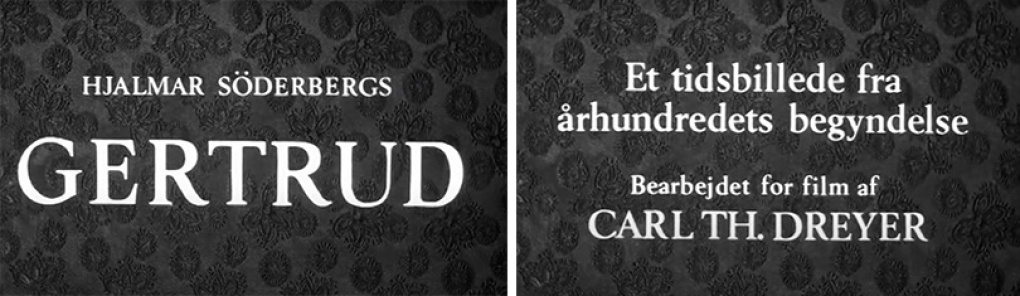

Dreyer cited Hammershøi as an influence (Roos’ documentary film, 1966): the parallels with Gertrud’s mise-en-scène are clear: severe surfaces, limited use of props, and subordination of protagonist to architecture, for example the preponderance of doors throughout the film. Fonsmark (2007, 3) writes: “Hammershøi and Dreyer share many thematic and formal analogies...They are both convinced that the greatest dramatic intensity is found in interiors – of a house, an image, a face. The enigmatic women … in domestic interiors refer to the contemplation and ecstasy of the characters and their personal dramas and even contain the hint of death.” The Danish critic, Poul Vad, declared Dreyer to be Hammershøi’s one true heir (see C. Claire Thomson, 2010).

Another key influence on Dreyer was the genre of the Kammerspiel. The term initially referred to the theatre’s design, particularly Reinhardt’s Little Theatre (Berlin, 1902), and Strindberg’s Intimate Theatre (Stockholm, 1907). They were constructed to create a more direct relationship between actors and audience. Key attributes of Kammerspiel style are: few protagonists depicted within a concentrated time frame; focus on mise-en-scène; and limited set changes. The first prop in Gertrud, the crushed velour backdrop to the credits (Fig. 3), is a stylistic reference to Kammerspiel and the period in which Gertrud is set. It thus establishes the prop as literal ground of the film. Interestingly, the piano music that accompanies the credits unrolling over the velour backdrop works rather against this historization: composed by Jørgen Jersild, it is modal and therefore ‘anchorless’ unlike the time specific/tonal music which was still prevalent at the time the source play was written (Debussy was the first composer to re-introduce modal music in his first book of Préludes composed 1909-1910, so the publication of the play precedes this by several years).

The mise-en-scène in Gertrud is filmed in a deliberately flattened perspective, which Deleuze referred to as the “crushing of depth and the planitude of the image” (1989, 39). The protagonists therefore are not privileged over their settings; in contrast, the surrounding objects/props are relatively prioritised against the usually foregrounded human figures, emphasising their importance.

Most props utilised through Gertrud remain ‘dormant’, they (merely) serve to demonstrate “the strained immobility of the bodies, huddled in armchairs, on sofas behind which the other silently stands…” (Rosenbaum 1986, 43). Others, such as the grand piano, are ‘activated’ by the action depicted in the film to encode further layers of meaning. Sparse in number, in adherence to Dreyer’s quest for “purification” with the excision of anything superfluous – “We compressed it, cleaned it, purified it, and the story became very clear.” (Cahiers du cinéma 1965, 117) – these props therefore resonate all the more powerfully.

The Deployment and Meaning of Props

1) The Piano

Music is central to Gertrud. Its influence is evident not just in the diegesis, but also in the film’s ‘en pont’, or bridge structure (Revault d’Allones 1988, 101), as well as its overall effect: Godard (Revault d’Allones 1988, 46) compared the film “equal in madness and beauty to the last works of Beethoven.”

The viewer learns in the film’s first minutes that Gertrud prior to her marriage had a career as singer. Music is represented in the film through the grand piano, visible from the opening scene in the Kannings’ drawing room. This initially appears pure convention, typical ‘furniture’ in an affluent turn-of-century household. Dreyer spatially positions Gertrud near the piano, whereas her husband, a lawyer, is predominantly depicted by his desk. Notably, the piano chez Kanning is neither referred to by the protagonists, nor played; it is mute(d), to be awkwardly navigated around.

Dreyer reintroduces the piano in the apartment of Erland Jansson, Gertrud’s lover, then once more in the private rooms of the banquet venue. Now the piano is physically activated as symbol, deployed to depict Gertrud’s self-expression in a social/familial environment, which she entirely fails or refuses to realise through the spoken word. As Rosenbaum (1986, 41) comments, “Consider her cracked, fragile voice which enters another realm entirely when she sings.” The piano’s role as signifier during these performances versus its sterile positioning in the previous scene embodies what Carlson defines as ghosting: “We might say that a signifier, already bonded to a signified in the creation of a stage sign, is moved in a different context to be attached to a different signified, but when the new bonding takes place, the receiver’s memory of that previous bonding remains, contaminating, or ‘ghosting’ the new sign” (1994, 12).

In Jansson’s apartment, the self-reflexive nature of art is suggested by the mirror behind the piano. The long circular shot around the piano – a cinematic device deployed only twice during the film – highlights Gertrud’s ‘altered state’ whilst singing. As Drum (2000, 256) notes of this scene, “… a kind of ethereal flare around the two people that gives not only a fascinating effect but also just the right mood.” The intense light from the window in the studio (Fig. 5, right) contrasts with the ‘dead’ window light in the Kannings’ flat, again highlighting how Gertrud – through the piano – has been brought to life. Gertrud’s ‘activation’ is made explicit through her touching of the piano (Fig. 5, right), an example of what Thomson (2015, 51) refers to as “artefacts transcend(ing) their status as props through tactile appropriation by actors.” It is of little surprise after this musical intimacy between Gertrud and Jansson – the first time the spectator hears her ‘voice’ – that their affair is consummated.

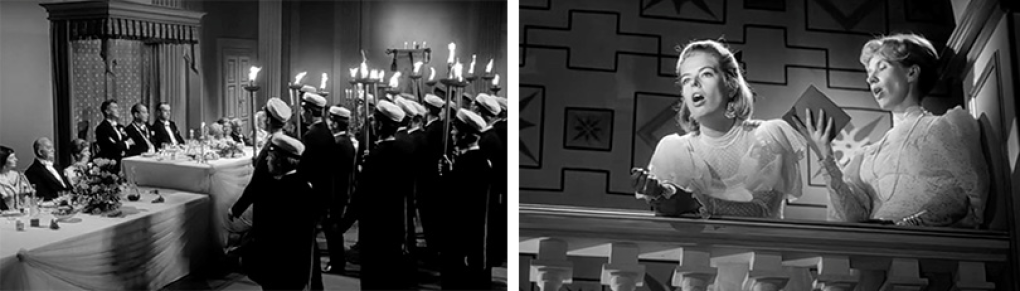

Between the two scenes when Gertrud sings, Dreyer interposes a musical interlude – not in the Söderberg source – during the banquet scene, with students singing an ode to the fêted poet, Gustaf Lidman, Gertrud’s former lover (Fig. 6). This chorus is depicted within the wide panorama of the banquet, scenically a sharp contrast to otherwise tightly enclosed interior scenes. Revault d’Allones (1988, 28) highlights the relevance of the inclusion of this public spectacle as counterpart to Gertrud’s two recitals: “It is this pivotal moment that contains Dreyer’s profound ‘message’: the hiatus between the tribune and the intimate song, between the falsity of the public word and the truth of private belief.”

Following this public spectacle, Gertrud retreats to a small salon to give her private recital, the second utilisation of the piano. Note, this time the piano as a prop is quite literally physically activated as Dreyer deliberately depicts it being wheeled into place from a previously closed-off antechamber. From a diegetic perspective, this action is unnecessary, and like the actual recital itself, is Dreyer’s inclusion, not sourced from Söderberg (who could arguably have included this as a stage direction had he considered it important). The piano finally rests half-way between the antechamber and salon, between private and public space, for Gertrud to perform for her husband and key dignitaries.

In his 1943 essay, “A Little on Film Style,” Dreyer (1973, 141) quotes Heine’s maxim that “where the words come out short, the music begins.” He again references Heine’s poetry in Gertrud’s choice of song for the recital, “Ich grolle nicht”, from Schumann’s Dichterliebe, op.48.,Heine’s poem, set to music, perfectly captures Gertrud’s predicament:

|

Ich grolle nicht, und wenn das Herz auch bricht, Ewig verlor’nes Lieb! Ich grolle nicht. Wie du auch strahlst in Diamentpracht, Es fällt kein Strahl in deines Herzens Nacht. |

I bear no grudge, though my heart is breaking, O love forever lost! I bear no grudge. However, you gleam in diamond splendour, No ray falls in the night of your heart. |

Overwhelmed, Gertrud collapses, the only truly ‘dramatic’ event in the entire diegesis, and one not included in Söderberg’s source. Deleuze refers to this as her “encounter with the unthinkable” (1989, 171). From the piano dominating the frame (Fig. 8 left), the low angle is retained as the camera pans back, highlighting the extent of Gertrud’s fall.

Not surprisingly, this scene is repeatedly referenced in scholarship: Schamus observes, “The failed performance before her private audience signifies the disjunction between verbal performance and image” (2008, 26). Other commentary, however, surprisingly deflects attention from Gertrud’s recital and collapse, focusing on the spatial relevance of the scene: Bordwell solely observes “Before she sings at the banquet, the wall behind the sofa is opened to reveal a door” (1981, 173); likewise Dana: “…when the rear wall which has so emphatically closured the scenic space from the very start, is opened for the first and only time so that the piano may be brought in” (1974, 57).

Bordwell’s examination of the previous performance by Gertrud, in the Kannings’ flat, similarly limits itself to a consideration of the construction of the scene, rather than what the scene signifies: “The tendency of the music to consume only as much time as the action does, no more, no less, turns the scene into a specimen of sound/image relations characteristic of the classical cinema” (1981, 184). Only in his epilogue does Bordwell refer to the texts sung by Gertrud: not the significance of what she sings, however, but how her performance has the “stylization typical of the film.” Bordwell proposes that as film, Gertrud cannot represent “the productive labour of musical performance” (1981, 200). Elsewhere (Neergaard 1963, Milne 1971, Carney 1989, Kau 1989), there is only fleeting commentary on Gertrud’s performances and no reference to the function of the piano.

Finally, it is worth referencing the piano, more particularly its substitution, in Gertrud’s epilogue. In the final version of the manuscript, Dreyer calls for Gertrud to be portrayed “sitting in a spartan, but tasteful study, which is dominated by a large grand piano” (1963, 61). In the film, however, the piano has been replaced as musical instrument by a cello. This substitution, I argue, is significant: the cello represents a new, ‘mature’ mode of expression for Gertrud in her independent, spartan existence 30-40 years after leaving her husband; it similarly marks a clear break with the musical modes of expression available to her in her former bourgeois existence. Its depiction suggests that Gertrud has returned to music, after abandoning it in her marital home. It also acts as metonymic signifier referencing the passage of time as well as Gertrud’s altered circumstances. Other such time signifiers depicted in her room together with the cello include the writing desk containing Axel’s letters, the bed with its closed fabric frame and the fireplace. References to modernity are the radio on which she reportedly listens to current affairs (a foil to the - more timeless - newspaper which her house help delivers during the scene) and the typewriter on which Axel reportedly wrote the letter. As Doxtater (2024, 168) observes, “Dreyer conveys this dignified old-young woman as more temporally ambitious. She remains elegantly unknown, embodying the past, future, and present all at once.”

2) The Statue

The statue first appears in the meeting in the park between Gertrud and Erland, the film’s second scene; it then reappears in the penultimate scene in the main body of the film, when Gertrud takes her leave from him.

The statue is not immediately revealed in park scene: instead, Dreyer creates an idealised establishing shot centred on the two lovers. Whilst both film and play are set in autumn, and the script (1963, 17) calls for fallen leaves on the ground, Dreyer references the lovers’ ardour though verdant foliage and dappled sunlight, a sharp contrast to the claustrophobic and sterile setting of Gertrud’s home. This sublime setting, filmed at Vallø Castle, contrasts with the source material: Söderberg also set the scene in a park, yet calls for a backdrop of barracks, factories and church spires (1921, 46), which Dreyer excised.

In this idealised setting, the camera slowly retreats from the lovers on the park bench to pan left, allowing the statue to enter the frame (Fig.11). The following static shot, over two minutes long, retains the statue firmly behind Gertrud as the couple talk of love and “rainbows of kisses”.

The statue, not formally identified, is clearly of Aphrodite of Knidos/Venus Pudica, the only Classical goddess to be portrayed naked. It seems little coincidence that Dreyer should chose as this key prop a (contemporary) copy of a Roman copy of a Greek original. It acts both as a link to other Hellenic imagery depicted in the film (see below) and, more importantly, draws attention to the film’s ontology and the relation of the embodied viewer to the depicted material object. At one level, the statue of the Goddess of sexual love and beauty operates as a representation of Gertrud’s love for Erland; the fact that it is always spatially closest to Gertrud and never shown above or near the couple, implies that the love is one-sided, not reciprocated by Erland, as proves the case later in the film. However, Praxiteles’ original statue also suggested chastity and catharsis. This implies that there is additionally a dialectic relationship between Gertrud and the statue, with the statue acting as counterpoint to Gertrud’s desires and referencing her innate modesty, and potentially, her sterility (the Kannings are childless). Note, this park scene is introduced before the consummation of the affair, and the cinematic technique deployed around Gertrud’s disrobement, detailed below, similarly alludes to her modesty.

The second, ‘mirror’ park scene has a distinctly more autumnal atmosphere, with the water of the lake unsettled, truncating the reflection of the trees compared to the first image (Figs. 11 and 12, both left). Gertrud remains associated with Aphrodite, although is now ‘reduced’ to sitting at the statue’s pedestal, looking in the opposite direction to the goddess. This time there are no shots of Erland including Aphrodite. This is a prime example of foreshadowing; the motif of Gertrud’s decoupling from Aphrodite anticipates her decoupling from Erland in the next take of the film. As with the piano cited above, the return of the statue sees it performing an additional formal function, dominating and dividing the frame in a manner that it did not in its first appearance. The distance between Gertrud and the statue, and the formal, seemingly emotionless, statis of both (Fig. 12, right) anticipates Dreyer’s short, Thorvaldsen (1949), in which he underscores the sculpturer’s “perfection of … composition … the scrupulous exclusion of private, idiosyncratic emotional responses” (Licht, quoted by Bogh, 1997 31).

Scholarship on these two park settings largely focuses on the scenes’ spatiality. Parrain (1967, 23) highlights the contrast between the inner/oppressive and natural/intimate setting in the scene shift from the Kannings’ drawing room to the park. Rosenbaum refers only to the “water in the pond … (which) forms a placid mirror to a stately line of trees” (1986, 43); Both Kracauer and Bordwell reference the props deployed in this scene, with Kracauer limiting attention to “the trees forming part of an endless reality which the camera might picture on and on, while the lovers belong to the orbit of an intrinsically artificial universe” (1997, 81). Bordwell acknowledges the statue in the context of perspective: “… representing this frontality most classically, in the figure of the frontally viewed nude female” (1981, 178). More recent scholarship has considered the relevance of the statue in greater detail, in particular Thomson (2010), who highlights how “the resolutely optical, as opposed to haptical, engagement with the Venus figure encodes Gertrud’s self-imposed spatial and emotional isolation in defiance of the venusian desires of the flesh.” A comparison is also drawn by Thomson to Michaël (1924), in which the moulded plaster statuette of Venus examined by the protagonists “gestures to the propensity of film to embalm the dead, to preserve the body that once lived and moved and loved.”

Arguably, the previous lack of critical attention on the statue might be because of the presence of another prop with more explicit reference to Gertrud, namely the tapestry, visible during the film’s longest scene, when Gertrud rests after collapsing during her recital.

The tapestry’s image of a naked woman, attacked by hounds in a setting not unlike the one used for the park scenes, acts as direct backdrop during Gertrud’s conversation with her former suitor, Axel Nygren. Spatially, the relationship between the two female figures is immediate and deliberate: it is worth noting that Dreyer changed the tapestry’s subject matter from a hind being attacked by hounds as in Söderberg’s play (1921, 58) to a woman. The reference to Gertrud is made explicit to the viewer, after the scene where Gertrud recounts to Erland that she dreamt of running naked and being attacked by dogs; she then repeats this dream to Axel (Fig. 13) whilst both are in front of the tapestry: “There, that is the dream I had last night.” Interestingly, the substitution in image from hind allows for another cross-reference to the park statue, since the figure depicted in the tapestry is Artemis/Diana seen naked by Acteon – Aphrodite as statue is similarly depicted bathing. In the myth, Artemis punishes Acteon for his impudence by turning him into a stag that is killed by dogs. Dreyer, however, inverts the myth, making Artemis the victim of the attack. This allows the tapestry to function as reference to the wider thematic of Gertrud’s oppression by men that runs throughout the film.

The ease of interpreting this prop as symbol of Gertrud’s fear of, and flight from, physical love has unsurprisingly proved tempting, explaining the numerous scholarly references to it. Carney writes, “The tapestry is … the stuff of human consciousness or made an extension of it” (1989, 321). It should be noted, however, that Dreyer himself explicitly argued – albeit in an obscure publication, a regional Danish newspaper, Fyens Stiftstidende, 28th February 1965 – against such an interpretation: “There is no Freudian symbolism in the dream. It is simply from sorry and trouble that she flies, not from physical love.”

Both statue and tapestry have visual and aesthetic function, directly linked to the protagonist. However, critics’ focus on the tapestry as the film’s definitive prop/symbol associated with the protagonist ignores the added resonance offered by the statue. Unlike the single scene featuring the tapestry, the statue adds the dimension of time, allowing for consideration of Gertrud at two key stages of the diegesis. Additionally, it provides a link –through supplementary reference to the Antiquities – to another crucial scene in the film, the consummation of Gertrud and Erland’s affair. First, there is a Hellenic pattern visible on Gertrud’s cape.

Secondly, and more significantly, is the Greek wall hanging depicted in the following scene in Erland’s studio. This decoration demands attention; it is totally incongruous with other props in the composer’s studio, such as von Beckerath’s famous portrait of Brahms (Fig.14, right).

The Greek decoration is only shown obliquely and therefore made difficult to read. No scholarship on Gertrud refers to it, perhaps because of its apparent indecipherability. However, the Metropolitan Museum of Art confirms it as a terracotta kylix attributed to Douris, c.470B.C. As shown above, it depicts two nude women putting aside their garments prior to bathing – an image of purity and catharsis, simultaneously referencing both the statue and tapestry. Whilst not depicted in the scene, it is worth noting that the exterior of the kylix (Fig. 16 right) depicts women together with younger men, a similar situation to Gertrud and Erland.

The kylix is only visible in the scene when Gertrud retires into Erland’s bedroom to undress. Dreyer denies the viewer direct access to this, capturing instead Gertrud’s denudement through an extended ghostly shadow (Fig.15, right) utilising a long-fixed camera shot. At the point when Gertrud’s body is supposedly revealed, it is instead desubstantiated. With Gertrud invisible, the kylix combined with her shadow transforms Gertrud to Gertrud-as-image, ontologically indeterminate.

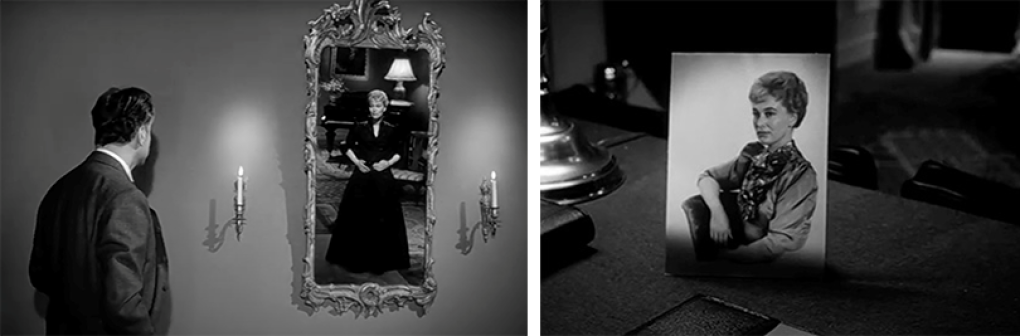

The thematic of Gertrud-as-image is developed further by Dreyer in the film utilising additional props: in ‘impossible’ mirror shots; and two scenes depicting her photograph being ripped up. Here, however, the image is not ‘self-sufficient’, solely referencing Gertrud as subject: rather its representation is Gertrud as patriarchal (art) object, “transformed into a fugitive succession of … wishes, memories and shadows” (Carney 1981, 93).

Conclusion

Demanding though Gertrud may be, I argue Dreyer offers a decoding device through his meticulous use and positioning of props. He was explicit that the props chosen for his films were to serve a purpose:

“These things are there for symbolic reasons. Even if the symbols themselves cannot be readily understood, I believe that the dominant mood of the development of the action on this purified background will be able to be sensed immediately” (1973, 184).

Scholarship’s has, however, largely focused on stylistic and filmic devices around the props, rather than considering them as devices for interpretation. Even historical artefacts included in Gertrud’s mise-en-scène – distinctive against the otherwise mundane portraiture – have been surprisingly ignored or misquoted. As with the kylix, no critic references the Munch Self-Portrait (1885) in Erland’s studio, which serves to associate Erland as artist with the forces of patriarchy that operate throughout the film. Similarly, the Munch lithograph, The Lonely Ones (1905),in the Kannings’ apartment – mirroring the emotional distance between Gertrud and Gustav as they take their final leave (Fig. 18, right) – has only been correctly identified by Revault d’Allones (1988, 80) and Drouzy (1984, 24).

To argue that “Gertrud simply offers itself as empty” (Bordwell 1981, 171) is to deny the presence of coding and reference systems bringing substance and meaning to the diegesis. First, these systems point to an authorial concern with content rather than merely with technique, a concern that remained constant throughout Dreyer’s career. At the start of his career, when filming Once Upon A Time (1922), Dreyer wrote, “The purpose of film is and will remain the same as theatre’s: to interpret the thoughts of others” (1922 10). In an interview in Cahiers du cinéma forty years later, he made precisely the same point, this time with specific reference to Gertrud: “What interests me – and this comes before technique – is reproducing the feelings of the characters in my films … That is what interests me above all, not the technique of the cinema. Gertrud is a film that I made with my heart” (Sarris 1967, 16).

Second, the subtle and repeated allusions to the art of the Antiquities highlight Dreyer’s preoccupation with cross-reference systems that permeate the film. They clearly illustrate the dichotomy between Gertrud’s character and her actions that the diegesis itself (deliberately) fails to highlight. Most importantly, they elevate this to a mythical level. This corroborates the non-naturalistic elements of the filming, as the film’s significance and treatment of this thematic extend beyond what is simply depicted in the Kanning household and its immediate surrounds.

Third, the intertwining of props and aesthetics permits a more life-affirming interpretation of Gertrud than has generally been offered. The epilogue depicting Gertrud 30-40 years later, which Dreyer added to Söderberg’s play, is critical in this regard. The epilogue was the first amendment Dreyer ever made to his source material in terms of adding a new scene not referenced at all in the source material and set at a time decades removed from the main body of the diegesis. Supported by the cross-referencing of the props utilised in the main body of the film – the replacement of the piano for the cello, the rejection of the patriarchal written word (in this instance, Axel Nygren’s letters) – Dreyer depicts here his protagonist in the final stage of her life. She calmly anticipates her death after what Thomson (2015, 49) refers to as the “quiet endurance of lived time”. Here, once more, Dreyer cross references temporality: the past/future of “I have loved” as anticipated in her childhood poem which is visibly depicted in the previous scene, and the reference to the inscription of ‘amor omnia’ which will stand on her tombstone, The bell chimes in the final seconds of the film both anticipate her death and this calm acceptance of solitude. The final prop, the closed door to her study, bathed in what Truffaut described as Dreyer’s “milky whiteness … something we have never seen before or since” (1980, 48), acts as symbol for a life that Gertrud finally considers well lived.

Notes

1. Unless otherwise stated, all translations from the Danish, German and French original are my own.

Bibliography

Bogh, Mikkel. (1997). Bertel Thorvaldsen. Copenhagen: Forlaget Palle Fogtdal.

Bordwell, D. (1981). The Films of Carl-Theodor Dreyer. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Burch, N. and Dana, J. (1974). “Dreyer’s Gertrud.” In: Afterimage no. 5: 57-64.

Carlson, M. (1994). The Haunted Stage: The Theatre as Memory Machine. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Carney, R. (1989). Speaking the Language of Desire: The Films of Carl Dreyer. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Debussy, C. (1910). Préludes, premier livre. Paris: Jacques Durand.

Deleuze, G. (1989). Cinema 2: The Time-Image. Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press.

Doxtater, A. (2024). Visions and Victims: Art Melodrama in the Films of Carl Th. Dreyer. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

Dreyer, C.T. (1922). “Nye Idéer i Filmen.” In: Om Filmen. Gyldendals Ugebøger, Copenhagen.

Dreyer, C.T. (1964). “Script for Gertrud.” Copenhagen: Det Danske Filminstitut. Accessed 1st March 2024.

https://www.carlthdreyer.dk/carlthdreyer/filmene/gertrud.

Dreyer, C.T. (1973). Dreyer in Double Reflection. Edited Skoller, D. New York: E.P. Dutton.

Drouzy, M. (1984). “Gertrud.” In: L’avant-scène cinéma. no. 335: 7-28.

Drum, J. (2000). My Only Great Passion. The Life and Films of Carl Th. Dreyer. London: The Scarecrow Press.

Fonsmark, A-B. (2007). “Catalogue for Hammershøi-Dreyer exhibition.” In: Centre de Cultura Contemporania. Barcelona. Accessed 11th March 2024.

http://www.art-of-the-day.info/a5415-hammersh-i-and-dreyer.html.

Heinrich, Heine. (1823). Dichterliebe. London: Faber.

Ibsen, H. (1879). A Doll’s House. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kau, E. (1989). Dreyers Filmkunst. Copenhagen: Akademisk Forlag.

Kracauer, S. (1997). Theory of Film. The Redemption of Physical Reality. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Kruuse, J. (1964) “Gertrud anmeldelse”. In: Jyllands Posten. 19th December 1964. Århus.

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. n.d. “Reference to Kylix”. Accessed 1st March 2024. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/251398.

Milne. T. (1971). The Cinema of Carl Dreyer. London: Zwemmer.

Munch Museet, Oslo. n.d. “Reference to Lithographs”. Accessed 8th March 2024.

https://www.munchmuseet.no/en/object/RES.A.00220.

https://www.munchmuseet.no/en/object/PE.M.00176.

Neergaard, E. (1963). Bog om Dreyer. Copenhagen: Dansk Videnskabs Forlag.

Parrain, P. (1967). Dreyer: Cadres et Mouvements. Paris: Minard.

Revault d’Allones, F. (1988). Gertrud de Carl Th. Dreyer. Paris: Éditions Yellow Now.

Rosenbaum, J. (1986). “Gertrud. The Desire for the Image.” In: Sight&Sound no. 55: 40-45.

Sandberg, M. (2006). “Mastering the House: Performative Inhabitation in

Carl Th. Dreyer’s The Parson’s Widow.” In: Northern Constellations: New Readings in Nordic Cinema. Edited Thomson, C. Norwich: Norvik Press.

Sarris, A. (1967). Interviews with Film Directors. Indianapolis: Merrill.

Schamus, J. (2008). Carl-Theodor’s Gertrud. The Moving Word. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

Söderberg, H. (1921). Gertrud. Skrifter, Femte Delen. Stockholm: Albert Bonniers Förlag.

Sofer, A. (2003). The Stage Life of Props. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Strindberg, A. (1888). Miss Julie. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Thomsen, C. (1989). “Mirakuløs eller monstrøs.” In: Kosmorama no. 35: 42-44.

Thomsen, P. (1968). “Working with Dreyer.”In: Dreyer Presentation Book. Copenhagen. Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Thomson, C. (2010). “The Artist’s Touch: Dreyer, Thorvaldsen, Venus.” Carl Th. Dreyer: Liv og værk. Det Danske Filminstitut. Accessed 19th August 2025.

https://www.carlthdreyer.dk/en/carlthdreyer/about-dreyer/film-style/artists-touch-dreyer-thorvaldsen-venus.

Thomson, C. (2015). “The Slow Pulse of the Era: Carl Th. Dreyer’s Film Style.” In: Slow Cinema, Edited De Luca, T and Barradas Jorge, N.. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Trolle, B. (1965). “Dreyer om Gertrud.” In: Kosmorama no. 11: 99-103.

Truffaut, F. (1980). The Films in my Life. London: Allen Lane.

von Beckerath. 1899. “Brahms am Flügel”. Oil painting. Accessed 25th February 2024.

https://www.bridgemanimages.com/en/noartistknown/johannes-brahms-portrait/nomedium/asset/3759762.

Filmography

Dreyer, C.T. 1922. Det var Engang (Once Upon a Time). Sophus Madsen Film.

Dreyer, C.T. 1924. Michael. Decla - Bioskop.

Dreyer, C-T. 1949. Thorvaldsen. Dansk Kulturfilm

Dreyer, C-T, 1964. Gertrud. A/S Palladium.

Roos, J. 1966. “Carl Th Dreyer”. Accessed 20th February 2024.

https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0060212.

Suggested citation

Peter Aurdal-Lawrence (2025), Deciphering Dreyer: Props and Symbols in Gertrud. Kosmorama #289 (www.kosmorama.org).