In 1949-52, top Danish short-film and documentary directors, including Theodor Christensen, Jørgen Roos and Ove Sevel, made a series of shorts about the positive effects of Marshall Aid in Denmark. The process around the production of four of the six planned films is a rare example of the production, in peacetime, of propaganda films initiated and sponsored by a foreign power, the United States.

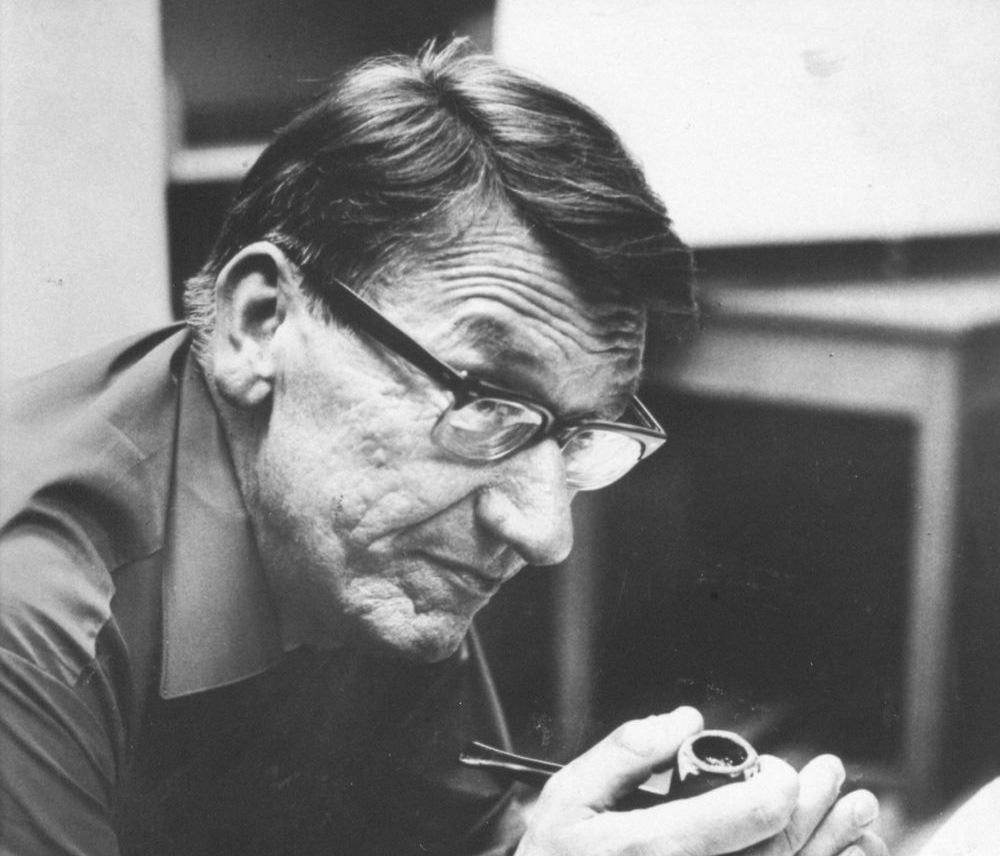

Cinematically, the Marshall films are not unusual compared to other Danish shorts of the time. Public information films had a very prominent place in Danish short film production in the 1940s and 1950s, and the Marshall films do not stand out from that tradition in form or style. Such short films were shown in cinemas before the feature, and during the German occupation they formed the background for a blossoming of Danish documentaries, including such seminal works as Theodor Christensen’s Iran – det nye Persien from 1939 and the controversial Det gælder din Frihed from 1946, which Christensen directed and co-wrote with Karl Roos.

The unique thing about the Marshall films was that a foreign power was taking the initiative, and partly paying, for a number of films produced in Denmark by Danish filmmakers for the overarching purpose of publicizing the importance of Marshall Aid to the nation.[1] Six months into the project, however, the Americans had to pull out for political reasons, when they got wind that some of the Danish directors had ties to communism. As a consequence, the production of the Marshall films ended up with a taint of the McCarthyist Red Scare, which makes the story of the films worth telling today.

American post-war propaganda

The background for the Marshall films, and American propaganda in Europe after World War II, was that the US did not want to be perceived to be using the Marshall Plan to infiltrate and control the European societies to which the aid was distributed. For this reason, the Americans chose to have the propaganda films about Marshall Aid to Denmark be produced by Danish film companies, with Danish directors and actors. This helped legitimise the films, so that they did not appear to be a mouthpiece for American interests. If the function of the propaganda was too obvious, and the message too banal and blatantly self-promoting, the Danes and the Americans alike were concerned that the propaganda would not have the intended impact on the population and would instead strengthen the criticism of the plan, by the Danish Communist Party (DKP) and the Soviet Union, as an American attempt to direct the economic policies of European governments and – after the founding of NATO in 1949 – their defence policies, as well.

In 1950, USIE (the United States Information and Education programme) set down an official American propaganda strategy stating that direct anti-Soviet and anti-communist propaganda should not be used in Denmark, because the population resists “any attempt to be propagandized.”[2] As the historian Poul Villaume writes, the American effort would instead go into quality publicity and information. This should partly be viewed in light of the negative experiences with Nazi propaganda during World War II. Moreover, the Americans wanted to use Danish media and organisations to communicate their message to the Danish population and thus hide or veil who was actually sending the message.[3] The Americans used this method in the production of the Marshall films, which are dominated by a standard of quality and fact-based content kept in a simple narrative form.

The campaign’s target group: ordinary citizen

As the historian Marianne Rostgaard writes, Danish officials in 1948 and early 1949 had no clear sense of what the American side was expecting in terms of publicity and promotion of the Marshall Plan. Moreover, Denmark was less advanced than the US in terms of creative press coverage and professional publicity.[4]

The Americans wanted to use carefully devised information and publicity campaigns to apply the big perspective – abstract economic statistics, international policy and huge cash flows – to the daily life of ordinary citizens. The Marshall films should show the benefit of Marshall Aid to the individual family, worker or farmer. Identification and consumption, materialism and freedom, democracy and cooperation were themes that should go hand in hand, so that the individual citizen could understand the benefit of Marshall Aid and to forestall any criticism that might threaten American interests in Europe. Stereotypical national representations were deliberately employed to have as broad an appeal as possible and ultimately unite the population around the Marshall Plan’s objective of rebuilding Europe and strengthen the ties between the US and Europe. The initiative to produce the Marshall films, in February 1950, should be viewed against this backdrop.

Concept proposal

The story begins in fall 1949, when the first American rough draft for the production of seven Danish short films was ready. Script ideas, with the working titles The Cow, The Pig, The Chicken, Farm Mechanization, Fishing, The Marshall Plan and Denmark and Danish Breweries, were the starting point for a production process that would take many unexpected turns over the next two years or so. The first two of these films were realised as Den strømlinede gris (The Streamlined Pig) (Jørgen Roos, 1951) and Fabrikken Caroline (Caroline the Factory) (Søren Melson, 1951). The two other finished films were titled Kyndbyværket (The Kyndby Power Plant) (Ove Sevel, 1951) and Alle mine skibe (All My Ships) (Theodor Christensen, 1951). The last two films that were planned, Fiskebiler (Fish Trucks)and Danmarks bidrag til Europas genopbygning (Denmark’s Contribution to European Recovery), went through a lot of conflict and internal difficulties and were never released, even though the photography was practically done.

The films that never were

The intention of the Marshall films was that they should be produced by Danish production companies for screening in Danish cinemas and, later, in the rest of Europe, wherever distribution was possible. The Americans wanted the films to emphatically highlight European cooperation, even at the expense of the national angle – a demand that would later conflict with the Danish government’s desire to bring out the national element. Moreover, the Americans wanted the films to depict the rationalisation, technologisation and scientification of industry and agriculture that the Marshall Plan’s economic aid was promoting. New methods and machinery should be showcased to the public to make it clear that Denmark was undergoing rapid development in its most important industries, a development contributing not only to the Danish national economy but also to the overall economic recovery of Europe after World War II.

The idea for a seventh film, The Marshall Plan and Denmark, stood out because it was directly based on a pamphlet published by the American State Department, laying out the purpose and significance of the Marshall Plan. The film would be a discussion film to clear up any misunderstandings about the Marshall Plan. The underlying motive undoubtedly was to forestall criticism from the political extremes regarding the purported American attempt to control economic policy in Europe and shape European societies according to American cultural ideals. It was also an attempt to prevent the emergence of new criticism by explaining the true facts of the Marshall Plan, as seen from an American perspective. Though the film was never realised, it does express an important theme of American propaganda for the Marshall Plan in Europe: forestalling criticism and showing the scope of US aid in the European societies.

Rejected agreement

The American eagerness to launch Marshall film production in Denmark comes to light on 1 January 1950, when an American draft agreement lands on the desk of Ebbe Neergaard, head of Statens Filmcentral (SFC). The contract proposes the production of eight to twelve short films to be finished just six months after the agreement is signed. Ministeriernes Filmudvalg, the Ministerial Film Committee, (MFU) will organise the production and recommend Danish directors, screenwriters and production companies for the Marshall administration’s approval. Distribution of the films in Denmark will be handled by the SFC, which is also committed to work for the greatest possible dissemination of the films in Danish cinemas. According to the agreement, the films shall be of the “highest commercial standard for motion pictures of a similar type.” The detailed 12-page agreement, which would give the Americans ownership of the rights to the films and entitle them to change their general content, was rejected for unknown reasons at a meeting of 17 February. From a Danish perspective, it was highly advantageous that the agreement was rejected. It would have given the Americans almost complete control of the production, while the Danes would have had to deliver a number of films of very high quality in a very short time, which the Americans could then reject if they failed to meet their expectations.[5]

The formal production agreement

Instead of an agreement, it was decided to let a two-page verbal note be the official document setting down the framework for the production. A draft of this verbal note was approved on 22 February 1950 at a meeting in the Danish Foreign Ministry. The note expanded the stipulations for the films’ production and secured the SFC the right to distribution in Denmark, Greenland and the Faroe Islands, while the SFC would also be able to distribute the films internationally upon agreement with the Americans. The Americans, however, would still have formal ownership of the films and the international distribution rights. The note differs from the agreement, expanding the timetable for the production to 1950-51 and stipulating that no less than six and no more than 12 films are to be made, while the Danes will strive to finish the first six films by 31 December 1950. The films will be approx. 300 metres each (running around 10 minutes) and have a Danish voiceover. As far as is known, Den strømlinede gris was the only film that was also made with an English-language voiceover for international audiences.

The content of the films was only very loosely defined:

“It is contemplated that the subject matter of such films will deal with recovery in Denmark and the extent to which this was made possible by the European Recovery Program, as well as Denmark’s place and responsibilities in an integrated European economy, and with technical aspects of production in Denmark.”[6]

The Americans had to approve the themes of the films and scripts, the Danish rights were considerably expanded from the draft agreement and the cooperation between the MFU and the Marshall administration, via the Economic Cooperation Administration (ECA), was emphasised as a principal element of the production.

Comparing the American draft agreement with the final verbal note, which presumably was prepared in close cooperation between the Danes and the Americans, one can conclude that the Americans had to compromise and cede more responsibility to the Danes than they had originally expected. The American demands in the draft agreement seem very high, considering the Danish film industry’s limited resources and personnel at the time. The draft agreement was probably rejected as unrealistic for that very reason.

Establishing the Marshall Film Committee

On 1 May 1950, a committee was set up to organise the Marshall film production, which included finding suitable production companies and coordinating the work between the Americans and the Danes. The chairman was Ebbe Neergaard of the SFC. He was joined by Henrik Hjort-Nielsen, a principal at the Foreign Ministry (Hjort-Nielsen actually took turns filling the post with Viggo Berg-Nielsen, also of the Foreign Ministry), while the Americans were represented by Thomas D. Durrance, Information Officer at the ECA. The three-man committee hired Nordisk Films Teknik, Minerva Film and Teknisk Film Co. to oversee the practical production of the films. The committee’s goals were for the first six films to be finished by October 1950 and for the total costs not to exceed 310,000 Danish kroner.

A list signed by Ebbe Neergaard on 1 May 1950 provides an overview of the planned films, stating the names of the proposed writers and directors and the films’ working titles. According to plan, the six films – Rapport om genopbygningen i Danmark, Koen, Grisen, Skibet, Fiskebiler and Danmarks bidrag til Europas genopbygning – would be written and directed by some of the top people in Danish short films at the time, including Søren Melson, Theodor Christensen and the brothers Jørgen and Karl Roos. The document also states that all aspects of the production would be supervised by the Marshall Film Committee, which has supervisory authority of the production.

The first press release

The first press release about the Marshall films is issued on 6 May. It stresses that, while the funding for the films is American, the purpose of the films is not to make propaganda for Marshall Aid but “first and foremost to convey information about Danish production and production-organisation to the Danish people as well as to other European countries and, to some extent, also to an American audience.”[7] The press release and an undated, confidential SFC document make clear that the original ambition, as mentioned, was to produce more than six films. The intention was to produce two series of films as well as an introductory and a concluding film. The first series would tell the stories behind well-known Danish products, such as bacon, eggs, butter and beer.[8] The second series would deal with the people behind the production and feature a worker or farmer talking about his life and work. Apart from these two series of five films each, four or five didactic were to be made whose “purpose was to influence special groups to organise their work so that Denmark would, above, be able to cut back on imports.”[9] The press release also mentions that only Danish labour and Danish companies are used in making the films.

In other words, this is a very national presentation of a project whose premise is international and in which the Americans explicitly wished to underplay the national aspect. The intention of the press release clearly is to forestall press criticism of the apparent paradox of picking directors, who resided on the far left and had been behind such fiercely criticised films as Det gælder din Frihed, to work with the ECA on a project that was supposed to present a positive picture of the Danish society to the outside world. They seem almost to have been expecting the project to be attacked, considering that the second sentence of the press release clearly points out that the films are not intended to be American Marshall propaganda. As it turned out, the project ran into problems other than press criticism of the Danish state engaging in propaganda on behalf of the US. The committee’s national twist on the project was also a problem as was the fact that the films were to be made by directors with close ties to intellectual, communist circles.

The red henchmen of the film industry

The first unofficial comments about some of the directors’ communist sympathies surface in a meeting at the Foreign Ministry on 31 May 1950. The minutes read, “If the films do not turn out well, it might give rise to criticism that most of the directors were known for harbouring communist sympathies.”[10] Even so, this opinion does not seem to trouble the present parties greatly. The scripts for the planned films had been vetted by the Marshall Film Committee and presented to Lothar Wolff, head of the Marshall Plan’s film department in Europe. Thus, neither the Danes nor the Americans were concerned about criticism arising from the fact that some of the directors were communists or communist sympathisers. Only if the films failed, there might be some criticism. This might seem rather naive considering the rampant McCarthyism in the years around 1949-50 and the Hollywood Blacklist that was enforced in 1946 and the next 10 years or so. The Danes did not seem to expect the American attitude to Communism to have any impact in a Danish context.

The reaction of the national press

Over the summer of 1950, several articles appear in the daily papers criticising the paradoxical choice of directors hailing from the far left. In Sorø Amtstidende, on 11 July, Hans Bagge kicks off the debate under the headline “Communists and Marshall films,” criticising Danish short-film production for being controlled by “a small circle of the communist minded,” whom he describes in very negative terms: “To be sure, communists in Denmark are only a small minority, but it is our sense that they are quite dominant in documentary films.” One wording, in particular, “Communists and Marshall films do not go together well,” is repeated in several other newspaper articles on the subject in summer 1950.

On July 14, Land og Folk reacts to the criticism, writing, “It is not a matter of ability but of political leaning, and so, in Denmark, too, there are people, not least among the press, who would like to see the un-American witch trials transplanted to Danish soil.” The communist party paper is the only voice, apart from Ebbe Neergaard himself, to publicly defend the directors against the attacks. Berlingske Tidende makes the biggest splash, in an article of 22 July, criticising the choice of directors and urging the hiring of new directors who are not characterised by preconceived ideological attitudes. The article also criticises the entire Danish short film community for stagnating because of inbreeding. “It should seem obvious to anyone beyond the singular ‘Land og Folk’ian’ interest sphere that a grim discrepancy between attitude and action exists, if people, about whom the unchallenged claim is made that they celebrate easterly oriented opinions and who, in line with ‘Land og Folk,’ are declared opponents of Marshall Aid in all other areas, should be the ones to enlighten the outside world about Denmark’s recovery by Marshall Aid….”

On 7 October and 8 October 1950, B.T. discusses the seemingly paradoxical choice of directors, under the headlines “When the heart is absent” and “Growing turmoil around the Marshall films,” and criticises the financing of the Danish share of the costs for being in a mess. On 8 October, B.T. writes, “This summer, however, doubts were raised from various sides whether the production and direction of these Marshall films had been placed in the right hands, and it was cause for astonishment when the suspicion could not clearly be dismissed that several of the short-film directors involved in the current productions are declared opponents of Marshall Aid.”

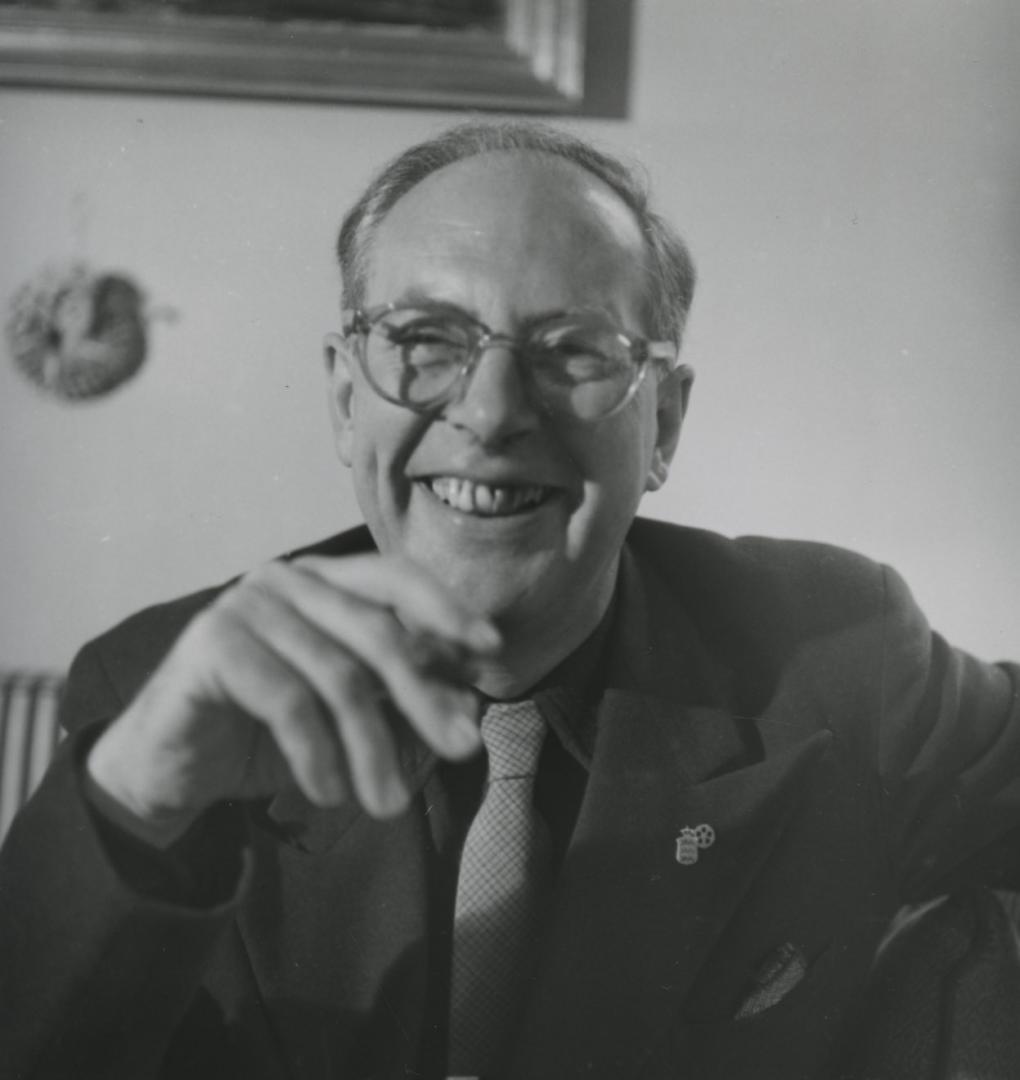

Ebbe Neergaard, it seems, singlehandedly had to answer the criticism. On 18 July, in Sorø Amtstidende, he tries to give the impression that there had been no American attempt in any way to influence the content of the films or slip in propaganda of any kind, either for Marshall Aid or for the USA in general. Neergaard writes that the Marshall films would “first and foremost serve to stimulate production within Denmark and as propaganda for D e n m a r k without. The representatives of the Marshall organisation have not put special weight on, much less tried to force through, the making of propaganda for Marshall Aid or for the United States of America.”[11] The editors of Sorø Amtstidendesubsequently criticise Neergaard for skirting the controversial issue of whether three directors have, in fact, been hired who have acknowledged having communist views.

Sorø Amtstidende and Berlingske Tidende’s criticism of the Marshall film project mainly revolves around a slightly paranoid fear that the directors would try to colour the films according to their own personal political convictions and that Danish short films in general were controlled by a sort of communist league that was only lacking control of Ib Koch-Olsen’s directorship of Dansk Kulturfilm. All the same, the criticism in the press never had the kind of impact that could effect changes to the film production or replace the involved filmmakers.

Neergaard’s defence

Neergaard’s defence of the Marshall films in the dailies does, however, present a somewhat image of the true facts of the case. Both before and after their official withdrawal from the film production, the Americans tried to get the Danes to highlight Marshall Aid in the films, primarily through the voiceover. The Danes accommodated the American requests to change the voiceover to give added emphasis to Marshall Aid. An American request to remove a newspaper headline that mentions the Korean War, in the film Alle mine skibe, was likewise accommodated, and the headline was no longer visible to the audience in the final version of the film.[12]

Neergaard has a clear interest in framing the benefit of the Marshall films in a Danish context and downplaying the films’ benefit to the Americans, including that the films could be shown in the rest of the world and create goodwill by showing American altruism and humanitarian cooperation with the Europeans. Neergaard tries to create the impression that he is not beholden to American interests and that the films he is overseeing are not dictated by American policy objectives.

On the other hand, Neergaard, in his article of 18 July, is correct in saying that the whole Marshall film production has been monitored and vetted by so many different bodies and persons that slipping in communist propaganda would have been impossible, if any of the directors had actually been trying to do so.

Furthermore, Neergaard tried to have the minutes of the 31 May meeting in the Foreign Ministry changed, so that the passage stating that “most” of the directors had communist sympathies would read “some” or “a few.” Neergaard points out that two of the said communists were excluded from the DKP in 1937 and had not since had any ties to the party. He also writes that “to my knowledge, none of the staff on the recovery films are communists or have communist interests.”[13] If the wording “most of the directors” had truly reflected the general tenor of the meeting, Neergaard says, he would personally have protested it, since it was not, to his mind, the result of the discussion at the meeting.

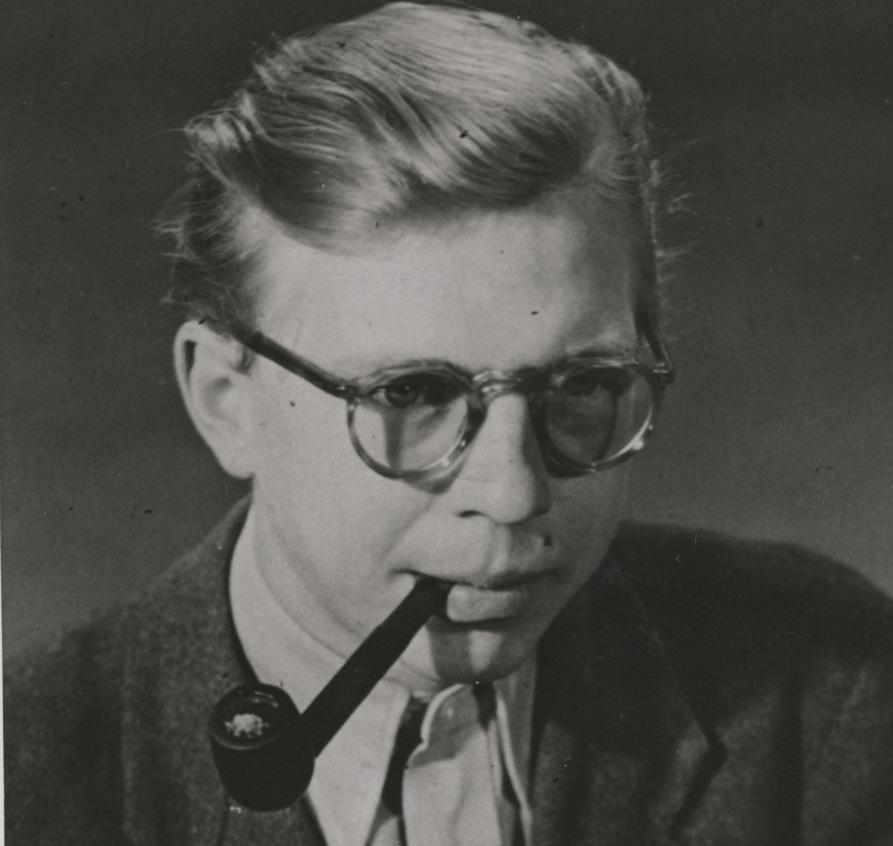

The paradoxical choice of directors, which was at the heart of matter, could very easily have been motivated on purely artistic grounds, since these were competent and highly experienced short-film directors. The choice of directors was surely based on their past film production and wide experience in the medium. It is also conceivable that Theodor Christensen, who had led a resistance film group during the German occupation, had built up a certain goodwill that would protect him from criticism. He notably made the protagonist of his film, Alle mine skibe, a former member of the resistance.

It was the cream of the Danish short-film community that was chosen to direct the six Marshall films, and it did not seem to have carried much weight that some of the directors were also or had been communists with lesser or greater degrees of conviction, including Karl Roos and Theodor Christensen who both wrote for the workers’ paper Arbejderbladet in the mid-1930s and, as students, had been members of the Danish Communist Youth League.[14]

American withdrawal

July 1950 was a turning point in the production of the Marshall films in Denmark. In a confidential note, dated 6 July, from the Foreign Ministry to the Ministerial Committee for Economy and Supply, it is suggested that a new agreement be negotiated, under which the Americans will withdraw their representative from the three-man committee, leaving full responsibility to the Danes, and the cost of the film production will be divided equally between the Americans and the Danes. The stated reason for these changes is that the previous agreement “contains disadvantages for both parties.”[15] The note emphasises that the division of costs is very fair from a Danish point of view, since the Danish population can benefit greatly from these films, which perform an important information and public-service function.

On 8 July, a formal request is presented for the Danish government to take full control of the production of the Marshall films and for the Americans to settle for an advisory role on technical questions and the like. Moreover, it is proposed that the Americans, who at this time had paid the first instalment of 25% of the total costs of all six films, only pay the next 25% instalment, while the Danes pay the remainder of the costs, or 50%, estimated at approx. 210,000 kroner.

Replacing films

In a letter to Neergaard of 7 July 1950, Lothar Wolff, probably in connection with the changes of early July, proposes replacing the first film, Rapport om genopbygningen i Danmark, with a new film about Kyndbyværket, a power plant on Isefjorden constructed in 1940.

The reason for the decision to replace Rapport om genopbygningen i Danmark with a film about Kyndbyværket is probably that Rapport om genopbygningen i Danmark was turning out to be a big and resource-intensive production and that a film about a subject closer to home and more familiar to ordinary citizens was preferable. A film about Kyndbyværket would be better able to serve American interests and promote Marshall Aid than Rapport om genopbygningen i Danmark, which did not directly touch on Marshall Aid but would be a remake of Tallenes Tale, a 1949 Danish short directed by Ole Sevel and commissioned by the MFU. Sevel was also supposed to direct Rapport om genopbygningen i Danmark but ended up writing and directing the film about Kyndbyværket instead. Perhaps, the Americans could see the advantage of producing a film about the most modern development in Denmark after the war, as represented by power production at Kyndbyværket, rather than simply focusing on traditional industry and agriculture, as in Den strømlinede gris and Fabrikken Caroline.

The American Red Scare

The question remains, what caused the Americans to officially pull out of the film project in July 1950. In a summary by the conservative Foreign Minister Ole Bjørn Kraft, dated 11 May 1951, he mentions that the Americans, by early July 1950, had become aware that some of the directors had a communist background and on that basis had decided to withdraw from the project. It is not known how Kraft came to posses this information, but his position naturally gave him access to information that ordinary officials and the filmmakers would not have had access to. The most plausible reason for the American withdrawal must have been fear of a possible scandal back home if the American public became aware that the ECA in Denmark had supported the production of six propaganda films by directors with communist ties. Although the communist directors acted in a professional manner and in no way tried to colour the films with their political ideas, the Marshall administration could not be linked to such a big assignment carried out by people with ties to communism. Retrospectively, it might be difficult to convince the American public that the directors’ political views had no influence on the content of the films. If problems were to arise anyway, the Americans could defend themselves by saying that they withdrew their support for the film production as soon as they learned about the directors’ communist sympathies.

Furthermore, the timing of the American withdrawal can seem calculated, since the production in summer 1950 was well underway and the whole project could not just be shelved if the Americans withdrew their support. The Americans had launched a project that mainly served their interests according to a carefully devised propaganda strategy, and no could accuse them of working with communists because they pulled out as soon as they were ostensibly first informed of the Danish directors’ political convictions. Once the project was in motion and shooting had begun, the Americans could withdraw, essentially without any cost to them. Instead, they could influence the films behind closed doors and downplay their role, while the Danes could have the outward appearance of being masters of their own domain.

Neergaard’s final report

In his final report on the production, of February 1952, Ebbe Neergaard is surprisingly reserved on the issue of American withdrawal. A prodigious writer, he himself had ties to communist journals and publishers in the 1930s, and as manager in charge of the film production he could conceivably be held accountable for the American withdrawal and the failure to complete the last two films.[16]Confirming Kraft’s persuasive analysis of the case, Neergaard writes, “Hence one cannot ignore that political misgivings could have played a role in the American withdrawal from the film production.”[17]

In his report, Neergaard seems – perhaps deliberately – to have misunderstood that nothing indicates that the Americans were concerned about communist propaganda being slipped into the films, but that they, for reasons of principle and ideology, could not continue to provide financial support to a film production in which some of the directors could be suspected of being communists. If communist views of one kind or another had been expressed in any of the films, the Americans would have spotted it, because they checked all significant aspects of the production. For example, in 1951, when Karl Roos was supposed to record a voiceover for an ECA-initiated, Swedish Marshall-film, he came under so-called political suspicion and was replaced by another narrator.[18] Roos’ name was later cleared and he was hired to record other voiceovers for Marshall films, including one for Kyndbyværket, before his death in 1951.

The tendency in Neergaard’s 25-page report is toward dismissing his own ties to communist circles and leftist views by pointing out that he was fired from Arbejderbladet because his reviews were not to the workers’ paper’s taste, and by arguing that, as a board member of Monde, he worked to keep the journal free of communist viewpoints.[19] Neergaard also stresses that he fully supports the Marshall Plan, even acknowledging the necessity of fighting the Soviet Union and communism because of their revolutionary imperialism.[20]

Neergaard uses the rest of the report to describe the process surrounding the individual films and the production troubles. He stresses that the Americans did not have the final say on the content of the films, including the voiceover, and that the Danes also had a certain say in the matter. Indeed, the voiceover was the most contested point in the films’ production. The Americans requested a lot of changes, which the Danes had to make. Production of the first four films was significantly delayed because of numerous rewrites of the voiceover. What is more, a lot of changes to the script of Fabrikken Caroline were made because the production involved agriculture consultants from the agricultural film committee, Landbrugets Filmudvalg.

In conclusion, Neergaard highlights the good cooperation and the amicable tone between the two parties, noting that the films turned out quite well and that the Americans were overall pleased with the final result.

The shelved films

The last two films, Fiskebiler and Danmarks bidrag til Europas genopbygning, were shelved on 18 July 1951 at a meeting, at Nordisk Film, between ECA representatives and Erik Witte, Theodor Christensen and Neergaard. Stuart Schulberg, who had succeeded Wolff as head of the Marshall Plan’s European film department, thought the footage for the two films lacked the required optimistic tone and faith in the future that the Americans were looking for.

Fiskebiler – a film about the long journey through Europe of Danish fish exports, following three Danish fish trucks to Vienna, Milan, Venice and Marseille – was dogged by accidents on the long road trips and script problems that required numerous changes.[21] Danmarks bidrag til Europas genopbygning was about Danish exports, engineering and humanitarian aid in several European locations, including Holland and Portugal. These two films were the most ambitious and demanding to produce and, in light of the American withdrawal, the Danes could not foot the bill and finish the films after Schulberg’s critique. Theodor Christensen worked on both films to improve the scripts, editing and voiceovers, but he could not save the footage, which Schulberg considered uninspiring and incoherent. Also, the films did not deal with productivity, which was a chief objective of the Marshall Plan at the time.[22]

The four finished films

A presentation of the first three films – Fabrikken Caroline, Alle mine skibe and Kyndbyværket[23] – was held at the Palladium cinema on 31 May 1951 for a group of guests from the ECA in Denmark and the Danish filmmakers involved. According to Neergaard, the reactions were mixed. Best received was Den strømlinede gris, which just missed being finished for the screening at Palladium. Neergaard himself ranked the film among the best documentaries that had been produced in Denmark in many years. Den strømlinede gris, with a score by Bent Fabricius-Bjerre, won an award at Festival Internazionale del Film Agricolo in Rome, 1953. Neergaard also singled out Alle mine skibe, with a score by Niels Viggo Bentzon and narration by Poul Reichhardt and Bodil Kjer, as a unique film that was worth every penny[24].

In B.T., on 18 February 1952, under the headline “200,000 wasted on worthless short films,” the writer Maurice noted that Fabrikken Caroline and Kyndbyværket were in international circulation and in demand in England and Sweden, among other places. Furthermore, Maurice wrote, Kyndbyværket was featured on the American TV show “One, Two, Three” and was a big hit. Finally, Maurice wondered about the problems that could have caused the shelving of the two most expensive of the films and looked forward to reading Neergaard’s recently submitted report on the production.

Conclusion

Outwardly, the Danes managed to play down that they were subservient to American interests and had to follow American directions and suggestions to a very wide extent. Neergaard, in his report, does not mention the plan to produce up to 12 Marshall films, nor the planned didactic films, and he generally avoids describing the key American influence on the fate of the films. The cooperation between the two parties was cordial, and in the democratic spirit they listened to each other’s opinions, but the Americans undoubtedly had crucial authority over the Danes, even though the Danes, who did the practical work, had a big impact on the basic cinematic style, composition and visual construction of the films. The films met the Danish goals for quality, and the Danes succeeded in highlighting the Danish benefit from Marshall Aid, even as the voiceover only very few times directly mentioned Marshall Aid.[25]

From an American point of view, the Marshall film production in Denmark around 1950 must be considered a success. Although several of the films never left the drawing board, the four films that were finished met the objective as positive publicity about the importance of Marshall Aid to Denmark and in a camouflaged manner served American propaganda interests in Europe during the Cold War. In January 1951, for example, Stuart Schulberg told Erik Witte that the ECA from the onset of their film programme declined to be mentioned in the films’ credits because “We feel such a title serves no purpose, except to advertise that the film is a paid propaganda subject.”[26] It must be assumed that the Americans also deemed discrete withdrawal to be the best way to distance themselves from an engagement with communist directors without calling undue attention to it back in America, while the country was busy fighting communism both at home and on the Korean Peninsula.

Translated by: Glen Garner.

Notes

[1] According to Sissel Bjerrum Fossat, more than 300 short films of the same type as the Denmark ones were produced in Western Europe between 1948 and 1954. Link to the essay: http://videnskab.dk/kultur-samfund/karoline-ko-blev-undfanget-i-propagandafilm [Tilbage]

[2] Villaume, Poul, Allieret med forbehold. Danmark, NATO og den kolde krig. En studie i dansk sikkerhedspolitik 1949-1961, Forlaget Eirene, Denmark, 1995, p. 772. Villaume is quoting from National Archives of the United States, Washington, D.C. [Tilbage]

[3] Villaume, op. cit., p 784. [Tilbage]

[4] Rostgaard, Marianne, Kampen om sjælene. Dansk Marshallplan publicity 1948-50. Jysk Selskab for Historie, Denmark, 2002, pp. 266-267. [Tilbage]

[5] The agreed amount of max. 840,000 kroner (70,000 kr. was the expected average cost per film, and no single film could cost more than 100,000 kr. to produce), which the Americans were willing to pay the Danes for the production of all the films, shows the importance that the Americans put on the project, which is also confirmed by the American eagerness to finish the films as quickly as possible. [Tilbage]

[6] Transcript: United States of America. Economic Cooperation Administration. Special Mission to Denmark. February 23, 1950. Signed: Chief of Mission Charles A. Marshall. (The Marshall Films 1944-1952, No. 1594). [Tilbage]

[7] Press release, Copenhagen, 6 May 1950, Denmark Making a Series of Short Films Paid For by Marshall Aid. (Ibid.) [Tilbage]

[8] Only the Americans were interested in making a film about the Carlsberg brewery’s latest production technology and scientific methods. [Tilbage]

[9] Plan for a series of short films produced by the Ministerial Film Committee for the ECA. Undated and unsigned. The working titles are Arbejdshygiejne (Work Hygiene), Græsmarksproblemet (The Grass Field Problem) and Fodringsproblemer (Feeding Trouble). (Ibid.) [Tilbage]

[10] Meeting minutes: On Wednesday, 31 May 1950, at 9:30 p.m., a meeting was held in the offices of Permanent Secretary Vilhelm Boas on the preparation of the production of the Marshall films. (Ibid.) [Tilbage]

[11] Article in Sorø Amtstidende by Ebbe Neergaard on behalf of the committee, dated 18 July 1950. (Ibid.) [Tilbage]

[12] It is remarkable that the newspaper headline “American advance in Korea” in Berlingske Tidende, a conservative paper, is being read by a welder at the B&W shipyard. [Tilbage]

[13] Letter from Ebbe Neergaard to H. Urne, an official of the Ministry of Justice, dated 20 October 1950. (Ibid.) [Tilbage]

[14] See also Villaume, p. 785, for a description of Theodor Christensen’s dismissal as a film critic at the state radio, Statsradiofonien, in April 1952, likely because of his background as a former member of the Danish Communist Party, DKP, and his critical reviews of American films. [Tilbage]

[15] Confidential, unsigned note to the Ministerial Committee for Economy and Supply, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Copenhagen, 6 July 1950. (Ibid.) [Tilbage]

[16] In his report, Neergaard writes, “In the early ’30s I expressed views that, although they in no way were party-communist, could be perceived as being tied to certain general communist ideas.” He also writes that he was never a member of the DKP and had had no contact with communists or communist circles since 1939, although, in 1934-35, he did write film reviews for Arbejderbladet (later Land og Folk) and published two books with Mondes Forlag and served on their board (Monde was an intellectual, communist journal first published in 1928). Based on an interview with Børge Houman, the historian Morten Thing writes, “When Neergaard returned to Denmark in 1945, he approached Børge Houman and offered to work for Land & Folk.” (Portrætter af 10 kommunister, Tiderne Skifter, Denmark, 1996, p. 117). Arne Hardis writes that Neergaard was a “communist-oriented intellectual.” (Klassekammeraten: Otto Melchior – kommunisten, der forsvandt, Gyldendal, Denmark, 2010, p. 80.) [Tilbage]

[17] Report on the Supervision of the Production of Marshall Films in Denmark 1950-51, Ebbe Neergaard, Copenhagen, February 1952, p. 7. (The Marshall Films 1944-1952, No. 1594.) [Tilbage]

[18] In a 1947 radio lecture, Roos strongly criticised Hollywood’s film production. See Rasmussen, Søren Hein and Rasmus Rosenørn (eds.), Amerika i dansk kulturliv 1945-75, Syddansk Universitetsforlag, Denmark, 2010, pp. 25 and 262. [Tilbage]

[19] Report on the Supervision of the Production of Marshall Films in Denmark 1950-51, Ebbe Neergaard, Copenhagen, February 1952, p. 8. (The Marshall Films 1944-1952, No. 1594.) [Tilbage]

[21] The director Svend Aage Lorentz recycled the idea for Fiskebiler in his 1958 feature Over alle grænser. Nørrested, Carl and Christian Alsted (eds.), Kortfilmen og Staten, Forlaget Eventus, Denmark, 1987, p. 297. [Tilbage]

[22] Report on the Supervision of the Production of Marshall Films in Denmark 1950-51, Ebbe Neergaard, Copenhagen, February 1952, pp. 16-22. Neergaard was palpably chagrined at the decision not to finish the films regardless. On 13 June 1951, Neergaard writes, there was an offer from Nordisk Film to finish the last two films for 32,000 kr. Neergaard did not agree with Schulberg’s critique of the footage, insisting that the footage for Fiskebiler was “quite lovely in its foggy lustre” (p. 23). (The Marshall Films 1944-1952, No. 1594.) [Tilbage]

[23] Fabrikken Caroline seems to be practically a remake of Koen from 1944. The director of both films is Søren Melson. The acclaimed author Martin A. Hansen was originally supposed to write the script but was dropped at the last moment. Alle mine skibe also seems to have been very much inspired by an earlier film, 7 mill. HK – En film om Burmeister & Wain, directed and written by Theodor Christensen in 1943. [Tilbage]

[24] The cost of each of the four finished films ran to between 53,500 kr. and 57,500 kr. The two shelved films were clearly the most expensive, costing a total of roughly 160,000 kr. (Nørrested et al, op. cit., p. 291.) [Tilbage]

[25] There was a lot of discussion about how many times the voiceover should mention Marshall Aid. Ultimately, much to the Danes’ satisfaction, it was decided that Marshall Aid could only be directly mentioned twice in each film. After internal disagreement among the Americans, it was decided to follow the official ECA order not to mention Marshall Aid directly more than twice in each 10-minute short film. [Tilbage]

[26] Letter from Stuart Schulberg to Erik Witte, dated 17 January 1951. In another letter, dated 8 January 1951, Witte asks Schulberg if the American involvement should be mentioned in the film. Witte describes the film Alle mine skibe as “A Danish short film produced with support from Marshall Aid” but implies that the Americans should decide whether they want to be mentioned in the credits: “Would you please inform me if you agree in this or what you would prefer?” (The Marshall Films 1944-1952, No. 1594.) [Tilbage]

Suggested citation: Kobberrød Rasmussen, Mathias (2013): The Marshall films and the red short film gang, Kosmorama #250 (http://www.kosmorama.org)

MATHIAS KOBBERRØD RASMUSSEN