It began as early as 1948 – on film – the tendency to question what a later age labelled a mythologizing portrayal of the occupation period. With Tre Aar efter (Three Years Later), Johan Jacobsen, the director, challenged the understanding that the Danish resistance movement was the only answer to the German occupation. Consequently, he questioned that the narrative of resistance should dominate the remembrance of the German occupation during the ‘five cursed years’, 1940-1945.

In Tre Aar efter, Holger Nielsen (Hans-Henrik Krause), one of the heroes from the resistance, despises and opposes one of the former collaborators, Andreas Hylmark (Ib Schønberg), a factory owner who has profited from his friendly relations to the German Wehrmacht. Hylmark is ‘værnemager’ – a term coined by Erling Foss, resistance fighter, co-founder of the Freedom Council, and later coordinator of relations with Sweden and the Soviet Union. As an ingenious combination of 'defense' [værn] and 'moneymaker', the term covered those who made money from trading with the Germans in various forms of collaboration (Christensen, Lund, Olesen og Sørensen 2015, 682).1

In this conflict, the sympathy of the film sides with Holger Nielsen. However, it is also made clear that the post-war situation needs the entrepreneurial spirit and economic know-how of persons like Andreas Hylmark. The resistance is so yesterday, and the resistance fighters have had so many difficulties adjusting their great expectations to the realities of peacetime. They fought for freedom and recognition of moral responsibility, not for the return of the politicians who had compromised Denmark’s reputation in the first place. However, the most urgent post-occupation task was to reestablish the economy. The fact that the future belongs to entrepreneurs such as Hylmark rather than outdated freedom fighters such as Nielsen is suggested by the final shot of the film. Nielsen’s old-fashioned car is overtaken by Hylmark’s brand new Hudson 1948.

In quite a different manner, Jacobsen’s ambition of puncturing myths was followed up in 1966. Formed by a childlike point of view, Klaus Rifbjerg and Palle Kjærulff-Schmidt's Der var engang en krig (Once There Was a War) represented a new type of realistic attitude to the occupation period. Focus was directed on everyday life in the family and at school, including experiences of meeting young German soldiers and trying to embarrass them. Klaus Rifbjerg commented the film in following way: "The film is a mixture of fiction and remembrance, and as such one of the most personal things I have made. […] A sober and factual and poetic depiction of a boy and his time, almost a parallel to my "Amagerdigte"" (Calum 1966). In Kjærulff-Schmidt's words, Der var engang en krig took up the task of "making a corrective to the historiography that has taken place around the time of the occupation. […] All those films from the time of the war are about houses collapsing and saboteurs going into action. But everyday life was completely different. We lived in a protected environment." (Stage 1966).

What kind of story did Jacobsen, later followed by Rifbjerg and Kjærulff-Schmidt, want to revise? It was first and foremost the dramatic story focussing on the resistance that – with few exceptions – had dominated historical narratives as well as cinematic representations throughout the period from the liberation in May 1945 to the beginning of the 1960s. During this period, the main perspective of occupation films was the resistance movement.

The purpose of this article is to provide an overview of the most important developments in the history of Danish occupation films since 1945. These films can be seen as a sensitive seismograph not only for changes, but also for nuances and even inversions in our understanding of the occupation era. But the importance of the films is not only of a seismographic nature. Tre Aar efter as well as Der var engang en krig are examples showing that films can help to shake common notions and perceptions, and these films do not stand alone. In my book Lange skygger. Besættelsen i film og serier (2025), a comprehensive history of main currents, genre developments, and critical reception of the Danish occupation films is presented.

The book is based on two main assumptions. The first one is that it is illuminating to understand the history of occupation films in the context of the historiography of the occupation period. The second one is that the history of the occupation film has its own dynamics. And this dynamic force is dependent on subgenres that emerge, perish and resurrect in new robes and with continued commentaries on both the predecessors and the present. Often these subgenres are based on international inspiration, but they are all adapted into a national perspective. Some films contradict the historiographical understanding by either being ahead of the historians' current insights or by denoting significant alternative perceptions.

In reviews and articles, the picture of the development of the Danish occupation films is often drawn as a transition from an idealising and mythologising tendency – typically with De røde Enge (The Red Meadows, Bodil Ipsen & Lau Lauritzen jr., 1945) as an example – to a critical, myth-busting tendency in many recent films. Thus, Roni Ezra, the director of 9. April (April 9, 2015), says, "There is a tendency to look inward and settle with the polished image of our history. If I have to see a common thread in films like Under sandet (Land of Mine, 2015), 9. April and Fuglene over sundet (Across the Waters, 2016), it is that they reshape the Danish self-image and puncture some myths." (Molin 2016). A similar basic understanding is inherent in Christian Monggaard's otherwise well-informed article from the 80th anniversary of the liberation (Information, 2 May 2025). The title illustrates this point of view: "Danish films about the Occupation have moved from hero portraits to the exploration of dark corners." Considering the whole picture, the development is not quite as simple.

In the following, I am going to outline the main positions in Danish occupation historiography that are a prerequisite for the "dark corners" gradually becoming part of the overall story – also on film. In similar ways, other occupied countries have had to come to terms with the period, and the concept of traumatic remembrance forms a common perspective for instance for the Netherlands, France, Norway, and Denmark. To frame my own approach, I shall briefly outline the historiography of Danish occupation films. My ambition is to show how these films relate to the historiography of the occupation. In doing so, I wish to highlight how they amongst myths and correctives follow their own paths, adapting various subgenres, styles, and points of view.

Historiography – the occupation period

When the liberation took place, the occupation period had to be worked through. The period had been marked by an appalling lack of information, fake news and an eternal struggle for finding reliable sources. The information brought by newspapers and radio was censured. It was not illegal to listen to news from the BBC, but it was hard coping with the German jamming. Gradually during the first occupation years, small illegal pamphlets were produced and distributed, presenting news from the perspective of the allied and the resistance movement. However, verification remained difficult.

For historians in the immediate post-war period, the urgent task was to find and preserve authentic, credible sources and shape them into a coherent narrative of the period with all its traumas and dilemmas. A distinction between four generations of historians and correspondingly four different concepts of the occupation was introduced by Danish historian Hans Kirchoff (2004) and is widespread in the historiography of the occupation today.

The concept of consensus

The most important person in the first generation was Jørgen Hæstrup, a high school teacher in Odense and a resistance fighter during the war. During the late 1940s, he took the initiative to collect material that became the basis of his dissertation, Kontakt med England 1940-1943 (1954). This marked the beginning of his position as the most prominent historian from the first generation. In this capacity, Hæstrup became a widely used consultant for occupation films.

Based on a political and moral rejection of Nazism, a ‘mythical’ account of the occupation, the so-called ‘consensus tradition’, arose (incidentally also internationally, for example in the Netherlands, Norway and France). In this, the resistance played a decisive role. Consequently, the history of consensus focused on everything that united the nation rather than what divided it. For many reasons, relating to domestic as well as foreign policy, ideological and pragmatic considerations, this understanding was pivotal up to the 1960s. As stated by Niels Wium Olesen, a later prominent historian:

The politicians won the power, the resistance as a concept won the credit. In the short view, the former was most important in terms of the stabilisation of the political system. The latter had a fundamental, decisive and far-reaching significance for our understanding of the occupation in a historical perspective (Olesen 2012).

With a common analogy, it was the narrative of the ambiguous policy as a combination of the shield and the sword. The cooperation policy was the shield that protected the Danes, while the resistance movement was the sword that fought the Germans.

The concept of conflict

In the long run, what divided was too significant to be held together by a single point of view, and the concept of consensus was replaced by the concept of conflict focussing on the many conflicting interests, ideologies and considerations that prevailed during the occupation. The concept of conflict was brought to the fore by the second generation of historians and labelled by Hans Kirchhoff (2004, 170).

Among the significant contributions of this generation was Aage Trommer's dissertation from 1971, which questioned the effectiveness of railway sabotage, not as a moral weapon, but as a tool to delay German supplies and troop movements. In addition, Ditlev Tamm's dissertation from 1984 problematized the legal settlement after the occupation. Tamm documented that the small collaborators who came first in the legal settlement were punished the hardest, while the larger ones, whose cases were typically more complicated and therefore took longer to settle, got away with repayment or fines (Tamm 2010).

The marginalized

Claus Bryld and Anette Warring are prominent in the third generation's understanding of the historiography of the Danish occupation with their main work on Danish collective memory Besættelsestiden som kollektiv erindring (1998). Bryld and Warring directed a scathing critique of the consensus tradition's emphasis on "spectacular and dramatic stories of resistance":

On the one hand, the popular motifs are sabotage actions and air drops of weapons, and on the other hand, events in which the Danish people's will to resistance and unity are highlighted: the August uprising, the rescue of the Danish Jews and the people's strike in 1944. (Bryld and Warring 1998, 67).

This focus meant that less flattering events in the overall story were marginalized. Bryld and Warring drew attention to the approximately 60,000 so-called ‘German girls’ who were girlfriends with German soldiers, and the 6,000 Eastern Front volunteers who, sanctioned by the Danish government, signed up for SS Division Nordland or Frikorps Danmark. Not to mention the many in the production industry who, with varying enthusiasm, collaborated with the occupying power, whether they were film or cement producers. Or the appalling story of the reception and treatment of the poor German refugees who had reached Denmark during the spring of 1945.

The third generation of historians pointed out all the less flattering events, circumstances, and points of view formerly marginalized. In this way, the myth of national unity again was undermined, but from a new angle:

Those on the wrong side had been perceived as social outcasts, as petty criminals and as stupid. They had functioned as the nation's alibi and prügelknabe. Now they were rehabilitated in the sense that it could be documented that their profile did not differ from the average of the population (Kirchhoff 2004, 173).

The concept of continuity

Continued research into the history of the occupation keeps producing revisions to the original narrative. In their comprehensive history of the occupation, Danmark besat. Krig og hverdag 1940-45 (first ed. 2005, revised ed. 2025), Claus Bundgaard Christensen, Joachim Lund, Niels Wium Olesen and Jakob Sørensen, the fourth generation of historians, present the concept of continuity.

Based on studies of everyday life during the occupation and focussing on the lines of development from the 1930s, the authors emphasise the positive role of these years. The 1930s meant not only the demilitarisation of the Danish society, but also a democratic commitment in large parts of the population that could counterbalance the Nazi ideology:

On important points, however, the vast majority of the Danish population showed great moral and political backbone and maturity, e.g. in the consistent rejection of the Nazi ideology. Here, the democratic development of the 1930s and the relative success of the Stauning-Munch government's policy of mitigating the consequences of the crisis played a role. (Christensen, Lund, Olesen and Sørensen 2015, 774).

The continuity thesis implies that the apparently irreconcilable views of resistance versus cooperation became each other's prerequisites. The emphasis on the importance of everyday life leads to a point of view that has been an essential premise in Dutch, French and Norwegian film historiography, namely the understanding of occupation as trauma.

The occupation as trauma

"Being occupied implies far more than dealing with the immediate consequences of military invasion, for the interventions of an occupying power permeate all aspects of daily life." This is how the Dutch researcher Wendy Burke formulates the fundamental trauma of the occupation in her book Dutch Occupation Film. Burke continues:

Long-term occupation creates a wholly different mood to that of active combat, yet there exists a similar tendency for a nation liberated from an occupying power to create and glorify heroes and martyrs and create positive narratives out of traumatic circumstances. (Burke 2017, 18-19).

Similarly, Leah Hewitt (2008, 11), professor emerita in French, emphasizes that the German occupation in France had an all-pervasive character that transformed the routines of everyday life. In France, which was both a resilient and a cooperative nation, the so-called "Vichy syndrome" became a key concept in understanding the consequences of the occupation period:

Like Belgium and Norway, France had had a government in exile that meted out punishment and praise upon its return in the early postwar years. Akin to previously occupied countries such as Belgium, Holland, the Netherlands, and Norway, or to the losers of the war (Germany and Italy), postwar France had to contend with muddled definitions of resistance and collaboration in its postwar purges of officials and companies who had had business (willingly or unwillingly) with the Nazis, or who had carried out their orders (Hewitt 2008, 2).

Right after the war, French historiography was characterized by defying the complicated realities in a one-sided focus on the resistance movement's heroic struggle against the occupying power – an approach that continued after 1958 in de Gaulle's idealized vision of a France that had heroically resisted the occupying power with only a few traitors (Hewitt 2008, 10).

Wendy Burke's presentation covers Dutch occupation films from the period 1945-1986. It takes its point of departure in a few traditional pairs of opposites: "the myth of the resistance (and its apparent opposite: collaboration), of 'good' and 'bad', of 'heroes' and 'villains'" (Burke 2017, 13). Following the development of Dutch society through the 1960s, 1970s and the first half of the 1980s, she examines the connection between the understanding of the occupation period in films and in collective memory. This includes the development from a state of trauma into what she, using an expression from the same terminology, calls historical healing (Burke 2017, 17):

The book argues for a progression from 'black-and-white' responses to Germany's 1940-1945 occupation of the Netherlands—reflected in the tendency in films of the early post-war decades to portray 'good' Dutch citizens against 'evil' occupiers—towards a much more nuanced, intricate image in later films of the moral choices faced by ordinary Dutch people during occupation. (Burke 2017, 12).

According to Marianne Stecher-Hansen's overview of "War historiography", collective trauma is a recurring feature in the Nordic countries as well. Everyone has had to deal with nationalistic narratives of patriotism and heroism in the face of a cultural memory of a traumatic occupation with a multitude of grey areas (Stecher-Hansen 2021, 18). Gunnar Iversen also uses the concept of trauma in his review article "From trauma to heroism: Cultural memory and remembrance in Norwegian occupation dramas, 1946-2009” (2012).

Historiography – the occupation films

A recurring theme in the history of the occupation films is a division into phases dependant on the development of the historiography and the trauma processing of which the films are a part. This approach supports the assumption that the period in which a given film is produced has a decisive influence on points of view and emphases in its representation of history.

Gunnar Iversen’s phase division of Norwegian occupation films (2012, updated 2018) is more complicated than Burke's – but it also implies more periods. Norway was occupied after two weeks (in Northern Norway two months) of war. While a nazi-orientated government with Vidkun Quisling as prime minister was installed in Oslo, the legal Norwegian government and the royal family escaped to England. Iversen also proposes four phases, which seem to be inspired by general Norwegian historiography. They can be schematically delineated as follows:

- Trauma (1946): the problematic and traumatized occupation drama that reflects the chaos of war by portraying existential and moral dilemmas.

- Collective heroism (1948-1962): dramas that focus on actual actions such as the sabotage of the Rjukan power station and the ship intended to transport heavy water to Germany, highlighting action rather than doubt, important for the shaping of the prevalent resistance story.

- Revisionism (1962-1993): dramas that focus on doubt, failure, and the non-heroic side of resistance in a showdown with the former dominant conception.

- Extraordinary individual heroism (1993-2016) – dramas that use the occupation and its spectacular actions to tell well-turned stories. During this phase living communicative memory transitioned into cultural memory (Iversen 2012, 239–240, Iversen 2018, 22).

Later Iversen expanded his understanding of the last phase including Kongens nei (The King's Choice, Erik Poppe, 2016) and Den 12. mann (The 12th Man, Harald Zwart, 2018) to show how resistance, struggle, and patriotism are increasingly dealt with under a Hollywood perspective that prioritizes extraordinary individual heroism (Iversen 2021, 311-312). Whereas some of Iversen’s phases can be recognized in a Danish context, one difference is striking. During prolonged periods, phases of collective as well as individual heroism have prevailed in Norwegian occupation cinema.

In Denmark, the historiography of occupation films began with the first Danish film history, Ebbe Neergaard's Historien om dansk film. From the vantage point in 1960, he notes that De røde Enge "was perceived by the general public as the monument of the resistance struggle" (128) – and this to a degree that made it difficult for successors. The relationship between the present and the past, and thus the influence of contemporaneity, is the overall approach in Dan Nissen's article "Modstandskampen på film" (1980). Nissen's analysis highlights how every historical film is dependent on the dominant perspectives of its time.

Ebbe Villadsen's brief, but influential, survey in Kosmorama (2000) applies a different approach. Villadsen suggests that fiction and fiction films "may ultimately give us a deeper understanding of the occupation" (Villadsen 2000, 6). Villadsen considers the first four fiction films as markers of two recurrent positions – a mythological versus a critical approach (Villadsen 2000, 15). Simultaneously, he argues that from the very beginning there are nuances in the films' interpretation of the period.

Ebbe Villadsen's article 'Besættelsesbilleder' (in Danish) in Kosmorama #226, 2000. Read in player or download PDF.

With thematization and aesthetics as his focal points, Ib Bondebjerg applies an elaborated stylistic approach in the chapter "Besættelsesfilmen" (in Filmen og det moderne 2005). In a similar vein, Birger Langkjær, in Realismen i dansk film (2012), deals with the complexity of realism in the first occupation films. Bondebjerg has continuously explored the relationship between history and mediated versions, expanding his leading point of view that history and memory are part of a constant battle of interpretation. Appropriately, the chapter thematizing occupation films in Film, historie og erindring (2023) takes its point of departure in the TV serial 1864 (DR, Ole Bornedal 2014), pointing out prevalent patterns of reception.

Although the emphases may differ, the tendency that initially characterized both the genre and the understanding of it – to understand the period on the background of the simple dichotomy between resistance and cooperation – is consistently disputed in the latest contributions to research. Tom Kristiansen summarizes this tendency and proposes replacing the dichotomy by a continuum: "a continuum stretching from armed to civil resistance, from enforced, pragmatic, and self-serving cooperation to ideologically inspired collaboration" (Kristiansen 2021, 53). This summary is characteristic of the part of current historiography that has settled with the consensus concept, accepted the lessons of the conflict concept and the necessity to involve previously marginalized groups in the overall picture. Kristiansen's continuum is reminiscent of the historiographic continuity concept, transferred into film. It is not dominant in Danish occupation films, but it is prominent in the film narratives of the 2020s that try to apply a point of view, covering the entirety.

Main lines and fractures

Considering the extensiveness of occupation literature and the number of occupation films that existed in other countries, Ebbe Iversen in 2000 wondered why Denmark had not produced more occupation films. But it was to come. A total of 34 films and 10 TV productions were presented to the Danish audience during the period 1945-2023. TV productions first exist from the 1960s. They are divided into TV plays and serials.

With a few notable exceptions, the films and TV productions are relatively evenly distributed over the years. The decade from 2000 to 2009 only counts one film. However, Ole Christian Madsen's Flammen & Citronen (Flame & Citron) from 2008 had a very great impact, also internationally, and represented a pivotal turn for the following development of the genre, quantitatively as well as qualitatively. With 11 films and one TV serial, the 13 years from 2010 to 2023 count almost one production per year.

|

1945-49 |

1950-59 |

1960-69 |

1970-79 |

1980-89 |

1990-99 |

2000-09 |

2010-19 |

2020-23 |

|

4 films |

3 films |

5 films |

3 films |

3 films |

4 films |

1 film |

5 films |

6 films |

|

|

|

1 TV play |

1 TV serial |

3 TV serials |

4 TV plays |

|

|

1 TV serial |

|

Statistics per decade of Danish occupation films and TV productions: 34 movies and 10 TV plays and serials. |

||||||||

The resistance film

In Denmark, the occupation film from 1945 to the early 1960s was characterized by the tradition of consensus that, as stated, focused on what united the nation rather than what divided it. For fifteen years, the serious and idealizing gaze dominated. The occupation film was born as a film exploring the relationship between resistance, cooperation and passion. In this triangle, resistance was emphasized. Den usynlige Hær (The Invisible Army, Johan Jacobsen, 1945) and De røde Enge (The Red Meadows, Bodil Ipsen and Lau Lauritzen jr., 1945) are the first two occupation films. Their genre-constituting character gives them a natural place as a starting point in any film history.

As we have seen, the two films have been seen as opposites, but several obvious common elements are distinct, related to the fact that both are shot close to the depicted events and dilemmas. Børge Thing, the leader of BOPA (a famous resistance group led by communists) was a consultant in Den usynlige Hær. The sabotage action was inspired by BOPA's sabotage against the Rifle Syndicate (Petersen 2015, 132), and extras from both BOPA and Holger Danske (another renowned resistance group led by liberals) participated. De røde Enge was based on a novel by Ole Juul, published in Sweden 1944. Leck Fischer, the screenwriter, had contributed to literary readiness in the illegal anthology Der brænder en Ild (1944) – as had Knud Sønderby, the screenwriter of Den usynlige Hær.

The most striking common feature, related to the closeness in time, is the films' thematic focus on the resistance movement as active resistance, illustrated by daring acts of sabotage that succeed despite great costs. The dramaturgy is built on an accelerating tension curve. Both films emphasize the necessity of sabotage and ‘liquidation’ 2, justified by German terror and killings (Den usynlige Hær), arrests, torture, and execution of resistance fighters (De røde Enge). In both films, the contradiction between life as a saboteur and the passion of love forms the backdrop for personal conflicts that help to promote identification.

Despite these common features, the first two occupation films define the genre in two different ways. The focus in Den usynlige Hær is doubts being overcome, whereas doubt never was strongly present in De røde Enge. The crucial differences lie in the portraits of the resistance fighters and in the endings. The triangle drama in Den usynlige Hær profiles Paul (Mogens Wieth) as a resistance fighter who during four long years in England has survived – and acquired the cynicism of professionalism. Returning to Danmark and confronted with Alice (Bodil Kjer), his unfaithful wife, the emotion of private life makes him forget basic principles of caution. Trying to escape from a flat in which he is trapped, Paul is killed by German gunfire. As a hesitant heir to his position in the resistance, Jørgen (Ebbe Rode), Alices’ lover, takes over Paul’s task in an imminent sabotage action. Thanks to Jørgen’s complete lack of experience he is also shot. Both heroes perish, and Alice is left, maybe to take over.

In contrast, De røde Enge exposes Michael Lans (Poul Reichhardt) as a freedom fighter of integrity, and he survives. Having narrowly escaped his execution, Michael succeeds in reaching Sweden, fulfilling his romantic promise to Ruth (Lisbeth Movin), who has already made the trip across the strait: "I always come home. You just must wait". Together with the sharp-edged confrontation between freedom fighters, executioners and informers, this determination and optimism contributed to De røde Enge's status as "the monument of the resistance" (Neergaard 1960, 128) – and later as a textbook example of a mythologizing attitude.

Related to the historiography of occupation, the first two films unanimously stress the importance of the resistance struggle – but they can hardly be accused of a wholehearted representation of the consensus concept as such. The image of the Danish population is in both cases miles away from the heroic. In Den usynlige Hær, the female protagonist's mother detests the actions of the resistance and finally informs against her son in law. Both films highlight how small a proportion of the population went into active resistance. "Look how few we are. At most one or two percent of the entire population," says Michael in De røde Enge, and the answer from the group's leader, Toto (Lau Lauritzen jr.), is in line with Michael's implicit criticism: "Now it's a question, when you look at it coldly and soberly, whether they deserve our efforts. They hear our shots and sleep on. They hear the bang of an explosion and dance on."

As stated in the introduction, the conflict concept was launched as early as 1948 in an occupation film. Johan Jacobsen's Tre Aar efter set the tone for the films and TV plays that later focused on one of the most tender points in Danish occupation history: the collaborationists and their roles in the post-war period. Remarkably, this film also included other sore points, for instance the ‘German girls’ and not least the freedom fighters' struggle to find their place in society after the end of the war (Agger 2024). The film pre-empted the later historical conflict research by satirically portraying the collaborationist factory owner and the cooperation politicians as the builders of the new age, and the resistance fighter as the one who had won recognition but lost the battle of the post-war period.

Comedies

In the early 1960s, the occupation comedy ushered in a radical break with the serious tone that had dominated the occupation films. Paradoxically, this rupture gave precisely the concept of consensus its most accomplished expression. In Sven Methling's Sorte Shara (1961) and Annelise Reenberg's Venus fra Vestø (1962), the main action takes place on a small, remote island, whose manageable population makes a living from agriculture, fishing and trade. In the local community there is an inn, a mill, a grocery store and a public authority. A small harbour provides the connection to the outside world.

To these peaceful, isolated communities comes the reality of war, in Sorte Shara when the Danish warships on August 29, 1943, received orders either to fight, sink or seek a Swedish port. In Venus fra Vestø, when the island is invaded by a force of forty German soldiers with the secret task of protecting “Lübeck”, a new German destroyer hiding at the shore. In both cases, a homogeneous population, regardless of class affiliation, spontaneously join the seamen and the locals who resort to resistance. With very few exceptions, the members of the population agree on actively supporting the resistance movement by providing fuel and food, by misinforming the Germans and helping to prevent their evil schemes.

Sorte Shara and Venus fra Vestø made the small island communities an image of the whole of Denmark in an idealized, humorous version of the narrative that ‘we’ unanimously stood together in the fight against Nazism – big and small, poor and rich, men and women, farmers and painters, Englishmen and Danes. Sorte Shara and Venus fra Vestø hit right in the middle of the consensus concept. The enjoyable idyll of the films became one of the factors in the cultural memory that supported the idea that the whole of Denmark was on the side of the resistance movement.

Childhood films

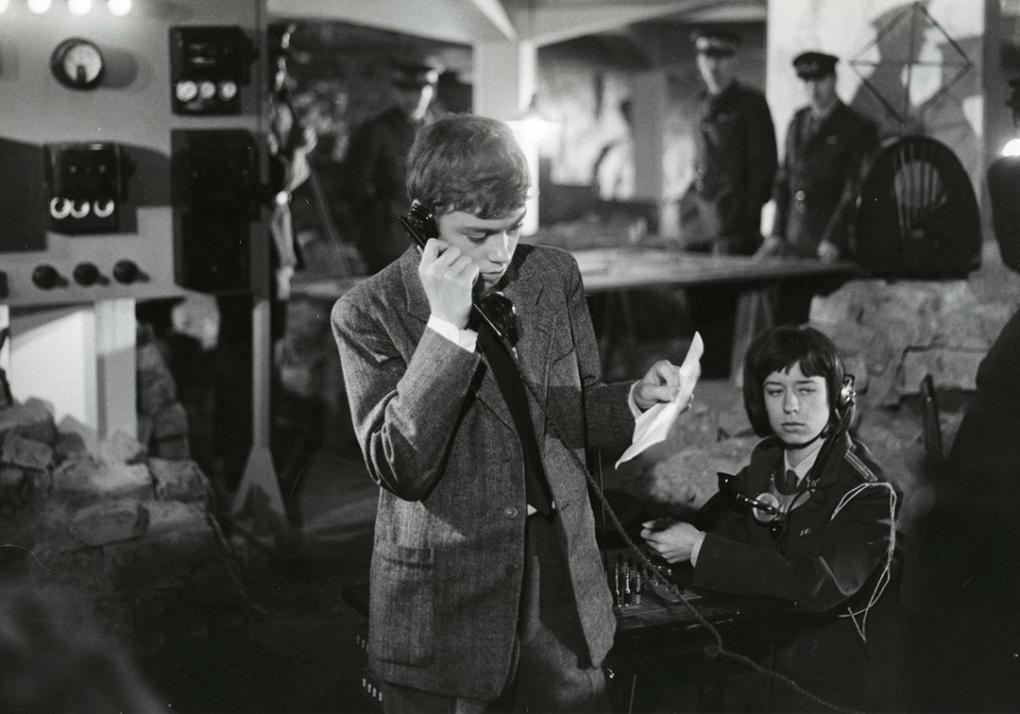

The next break with the traditional resistance film took place with a film in quite another subgenre, the childhood film. In 1966, the perspective of a 15-year-old boy transformed the mythological glow from De røde Enge. The dream sequences in Der var engang en krig show the simultaneously attractive and repulsive nature of life during the occupation. The resistance fighter is the ideal image in which the young Tim (Ole Busck) tries to mould himself, but everything in his everyday life contradicts the heroism – his family, his school, his first amorous attempts. Precious is the first dream scene where Tim appears in a rescue operation at Christiansborg, the Danish parliament. "They've called twice from London today," says the secretary, and then follows Tim's inimitable conversation with Winston Churchill, the undisputed leader of the war: "Hello, Winston, it's me. [ …] I know that it is important, but I cannot leave now".

The 15-year-old's acquisition of experience is symptomatic of the curious-interested observation that the childhood genre embraces. Psychological realism unfolds especially with Tim's perceptions of the world as it is, as he would like it to be, and as he fears it will be. Details of the time tracking is indicated by Tim's triple mode of attention, visualized by pins. Tim indicates the course of the war by placing pins on an atlas of Europe. But he is also busy putting pins in a completely different place, namely in the lap of a woman's torso in a book. And when Lis (Yvonne Ingdal) has rejected him and his friend Markus with a contemptuous “Babies", Tim torments himself by sticking pins through the skin of his hands.

The childhood film as a genre helped formulating some of the urgent conflicts, later pointed out by conflict-orientated historians. It pointed out the necessity of reflecting on the different perceptions of the occupation by different generations. Later, salient dilemmas of the period were further elaborated in childhood films such as Ole Bornedal's Skyggen i mit øje (The Bombardment, 2021) and Anders Walter's Når befrielsen kommer (Before It Ends, 2023).

Thematizing the marginalized

The third generation of historians have had a remarkable influence on the occupation films' choice of themes and points of view. During the 1970s and 1980s, focus became directed towards the marginalized rather than the resistance fighters – ‘German girls’, German soldiers, Danish Eastern Front volunteers joining Frikorps Danmark, and the German refugees in a continued showdown of the myth of national unity. During the same period, directors stopped portraying resistance fighters as pure heroes. Accordingly, Kjærulff-Schmidt's prospect from 1966 of delivering "a more nuanced picture" was followed up by directors from Ole Roos to Nicolo Donato and in the 21st century Anders Refn. Several new occupation films followed, characterized by reversals emphasizing the sore points of the occupation.

Den korte sommer (Brief Summer, Edward Fleming 1976) changed the prejudiced image of the ‘German girl’ into a more nuanced portrait. Being on the verge of divorce with her husband, Kirsten (Ghita Nørby), the female protagonist and her son Birger (Casper Bjørk) join her parents in Hjørring, a provincial town in Northern Jutland. She is a woman who unavoidably attracts men, and suitors queue up. However, she falls in love with the most unsuitable of all, Eugen, a German officer (Henning Jensen). Moreover, Eugen is about to leave. Having loved and being left, Kirsten fulfils a common social destiny among the ‘German girls’, but she never admits having committed an error. Kirsten is depicted as an unusually beautiful and attractive (though not a very sympathetic) woman. She is extremely selfish in her relationships, not only to her mother, but also to her son. What is emphasized by the film, however, is that she is not a scheming woman, nor a traitor to her country. This point of view was inspired by the women's movement of the 1970s, as was later the TV serial Jane Horney (Stellan Olsson 1985).

Over time, focus was increasingly directed at the stories of German soldiers and Danish Eastern Front volunteers. The stereotype supporting roles were replaced by expanded lead roles. It began with Befrielsesbilleder (Images of a Relief), Lars von Trier's controversial graduation film from the National Film School of Denmark in 1982. Trier’s point of view represents a frontal showdown with any traditional kind of understanding the resistance by presenting a German story of suffering and placing the sympathy with the defeated.

Forræderne (The Traitors, Ole Roos, 1983) continued the story of the losers by focusing on two basically quite ordinary young men whose ideological convictions have faded, or perhaps never existed. As deserters from Frikorps Danmark, they are hunted by their own SS-company as well as the resistance movement. Finally coming home does not bring any solutions.

In the 21st century, Martin Zandvliet completed the reversal of roles with Under sandet (Land of Mine, 2015). After the liberation May 5th a group of young German soldiers were ordered to disarm the 1.500.000 land mines spread on the West Coast of Jutland. During the immediate post-war period, the use of German soldiers for this purpose was not contested (Jensen 2025). While the Germans in this film are portrayed from a victim's perspective, the new view of the Danish freedom fighters implies their transformation into brutal, hateful commanders, almost executioners. Void of sympathy for the German boys they are treated condescendingly – in essentially the same manner as Gestapo used to treat Danish freedom fighters, using threats, humiliation, hunger, exposing the boys to a daily risk of death in clearing the mines. Only slowly one of the Danish leaders rediscovers his humanity.

While the 20th century films about the Jews' flight to Sweden in October 1943 is based on the consensus point of view, the opposite is the case in Nicolo Donato’s Fuglene over sundet (Across the Waters, 2016). Former flight films such as Bent Christensen’s Oktoberdage (The Only Way, 1970) emphasizes the citizen’s courage during the – mostly successful – rescue operation. Thanks to a huge civilian effort in October 1943 approximately 7,000 Danish Jews were transported to Sweden. However, an operation under these circumstances could not take place without accidents, and approximately 500 Jews were captured and deported to Theresienstadt, a concentration camp in the former Czechoslovakia

Fuglene over sundet tells the tragic story leading to the capture in Gilleleje church. It is a story of greed (on the side of Danish fishermen), desertion (on the side of the organizers), desperation (among the Jews caught at the ceiling of the church in Gilleleje) and death (Arne Itkin (David Dencik), the main character).

With Anders Walter’s Når befrielsen kommer (Before It Ends, 2023), the German refugees became the main theme of an occupation film. Like Der var engang en krig, the child's perspective prevails, in this case to emphasize the helpless situation of the refugees and their urgent need for help, even if they represent a repulsive enemy. As in Under sandet, the question is how to keep up a humanitarian attitude towards some Germans in a situation characterized by a general heartfelt hatred of all Germans.

The resistance tradition revisited

Film thematizing the marginalised were not the only type of films during the last decades of the 20th century. In 1991, two films appeared that in a peculiar way belong together, namely Søren Kragh-Jacobsen’s Drengene fra Sankt Petri (The Boys from St. Petri) og Morten Henriksen’s De nøgne træer (The Naked Trees). As a common feature, both films found their location in a provincial town – with a cathedral school or university, hospital, and a large church – a fictive Aalborg and Aarhus, adding authenticity to the narrative.

Revisiting the core questions of the first occupation films – the relationship between resistance, cooperation and passion – both films stress the importance of the resistance struggle, omitting any melodramatic touch. Instead, a matter-of-fact realism is applied, with a loving sidelong glance at the townscapes and their environments.

After the success of Flammen & Citronen in 2008, resistance films had a renaissance drawing on well-known international genres, but with new twists. With Danish soldiers' participation in the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan and consequently Denmark's status as an allied nation in a coalition of willing, the history of World War II presented itself in a new, topical light. Through its connection to real people and events, the biopic proved particularly well suited to zoom in on this seriousness.

Flammen & Citronen was based on the last months of the lives of Bent Faurschou-Hviid (‘Flammen’) og Jørgen Haagen Schmith (‘Citronen’), two resistance celebrities, who both lost their lives in October 1944. Surrounded by Germans, Bent Faurschou-Hviid committed suicide. Confronted by a similar situation only one week later, Jørgen Haagen Schmith fought back and eventually was shot. The film focused on the importance of resistance and the individual courage of the protagonists, but also on the debatable legitimacy of ‘liquidations’, providing a thematic and stylistic twist to the traditional resistance genre. At the same time, it delivered an intimate portrait of the performers, in a style close to predecessors such as Jean-Pierre Melville (in L’Armee des Ombres, 1969) or even Tarantino’s gangster films.

Vores mand i Amerika (The Good Traitor, Christina Rosendahl, 2020) is another good example of options provided by the biopic. With the portrait of Henrik Kauffmann (Ulrich Thomsen), the Danish ambassador to the USA, who claimed to represent the free, not the officially cooperating, Denmark, the film shows what a one-man army of his caliber could accomplish. ”I’ll work for the re-establishment of a free Denmark”, he declares in a radio-transmitted speech resulting in an accusation of treason from the Danish government. Individual courage and heroism are mitigated by stressing the complicated relationship between Kauffmann, his wife Charlotte (Denise Gough), and Charlotte’s sister Zilla (Zoe Tapper) with whom Kauffmann is in love.

Hvidsten Gruppen (This Life, Anne-Grethe Bjarup Riis, 2012) and Hvidstengruppen II – De efterladte (The Bereaved, Anne-Grethe Bjarup Riis, 2022) tell the story of Marius Fiil (Jens Jørn Spottag), an innkeeper, his wife Gudrun (Bodil Jørgensen), their children and their spouses. With their neighbors this family formed a resistance group in Jutland, receiving weapons and agents from Special Operations Executive (SOE) 3, delivered by English airplanes. Highlighting life in the countryside and the effort of ordinary Danes, these films renewed the original pathos of resistance films. Drawing on material from archives, letters and biographies they resumed the serious tone of the initial tradition, even to the point of pathos – a feature disliked by many critics. The great accomplishment of the films is that the female face of the resistance movement appeared far more pronounced than ever before.

Where Flammen & Citronen maintains a certain distance to its protagonists through style and genre, Hvidsten Gruppen and De efterladte invite their audience to participate in their lives – and deaths – without reservations. In both cases, the audience responded positively. The merging of the biopic genre into the occupation film was rewarded at the box office. Flammen & Citronen obtained 673,764 admissions and Hvidsten Gruppen even more – 755,010 admissions.

Continuity drama

The "continuity thesis" from the 2000s (Christensen, Lund, Olesen and Sørensen 2015, 772), put forward by the 4th generation of historians, was heralded in TV fiction earlier than in historiography. It is easier for TV serials than for films to imply historical preconditions due to the broad scope that can be unfolded in several sequences as the years pass. The continuity angle invites to consider the coherence of events over time.

On TV, it was already displayed in Matador (Erik Balling, Lise Nørgaard et al. 1978-1982). Here, the social and political upheavals of the 1930s are highlighted as an important background for the presentation of the occupation period and its dilemmas.Similarly, Badehotellet (The Seaside Hotel, Hanna Lundblad, Stig Thorsboe, Hans Fabian Wullenweber, Jesper W. Nielsen et al., 2014-2024), inspired by Matador, has an unerring eye for preconditions in the history of the 1930s.

Considering this advantage, it is no surprise that De forbandede år I (Into the Darkness, Anders Refn, 2020) originally was planned as a TV serial (Monggaard 2020). After years of planning, the project was abolished by DR. Instead, a film trilogy gradually took form, aiming at presenting the whole picture. As an allegiance to the original plan, in 2024, the first two films were divided into sequences and transmitted by TV2.

The synthesis film

The most ambitious attempt at connecting different ways of viewing and different occupation film traditions is represented by De forbandede år I and II. The first part focuses on the period 1940-1943 highlighting how collaborators in government and industry rooted in the pre-war policy of neutrality try to carry on their business as usual. As an owner of the factory Elektrona, Karl Skov, the main character (Jesper Christensen) is an important industrial entrepreneur. Significantly, he keeps up his business (and family) associations with neutral Sweden during all the occupation years. The second part returns to the resistance genre, depicting sabotage actions and their consequences, for the resistance movement as well as for the private lives of the protagonists.

The third part (making the films into a trilogy) is due in March 2026, the title being De forbandede år III – Fredens pris. According to a press notice from Scanbox March 13, 2025, it “illuminates a rarely depicted chapter in Danish history”, namely the legal answers and decisions to the question of allocating blame and responsibility after the occupation, the so-called ‘retsopgør’ [the legal reckoning]. Perhaps this film will provide the occupation film with yet another subgenre – the courtroom drama that is otherwise only present as an appalling parody in which the power of prosecution in a minute outmanoeuvres the pretended defence. This is the case for instance in De røde Enge and Hvidsten Gruppen.

De forbandede år I is the first film since Tre Aar efter that scrupulously dissects the heart and mind of the ‘værnemager’. In the beginning, Karl refuses to collaborate, he mortgages the family’s residence but must still fire 30 people. Meanwhile, everyone praises themselves for not having ‘Norwegian conditions’, which is used as a scary image. At New Year 1940, the factory is about to go bankrupt. Karl cannot survive financially if he does not conform. His reluctance to give up the factory is partly due to the fact that he is a self-made man, partly to his concern for his workers, his family and their way of life. His compliance marks the beginning of an economic increase and a moral decline.

At the beginning, it is just a question of production for civilian use in Germany. After some hesitation, Karl – with reference to F.L Schmidt and Aarhus Oliemølle, two large collaborating industrial enterprises – indicates that the factory may even be interested in expanding to occupied territories in Eastern Europe. Based on documented ideas among former CEOs, this illustrates how desperate some businessmen were to comply. Later, the Germans demand the conversion of production for military use. The factory is invaded by German engineers, and the owner is deprived of all control. In the end, Karl doesn't feel that he has done anything wrong: "I have followed the existing laws and regulations to the letter". As Karl is a likeable character who cares for his workers as well as for his family, this raises the question for the viewer: What would you have done?

Where De forbandede år I is a ’værnemager’-film, its sequel, De forbandede år II is a resistance film. Appropriately, its subtitle is Opgøret (Out of the Darkness). De forbandede år II resumes the traditional resistance film ingredients such as the ‘liquidations’ of traitors and the executions of resistance fighters. 1943 is depicted as a turning point. The German defeat at Stalingrad leads to a stronger resistance movement, eventually causing the declaration of state of emergency by the occupying power August 29, 1943. Consequently, the cooperation policy collapses, and with the introduction of death penalty the Danish government resigns. The German response is the persecution of the Danish Jews during October 1943.

From the beginning, Aksel (Mads Reuther) is characterized as the most belligerent person in the Skov family. “I have to do something,” he says in the spring of 1942, echoing predecessors such as Lars (Tomas Villum Jensen) in Drengene fra Sankt Petri, ”Somebody has to do something”. In De forbandede år II, Aksel’s inclination is accompanied by another passion, bringing female resistance into focus. Aksel is seriously in love with Liva (Kathrine Thorborg Johansen), an attractive and independent young woman. Although Liva rarely promises anything, she becomes Aksel’s entry into the resistance movement – the communist section, which since the Cold War has been neglected in most occupation films. Here, Aksel’s knowledge of chemistry from The Technical University of Denmark can be used in the manufacturing of explosives for sabotage. Meanwhile, his relationship with Liva is characterized by equal parts of passion and forced resignation. Liva is the epitome of the independent communist woman. She is the one who gives orders and chooses her lovers, not the other way around.

Eva, Karl’s wife (Bodil Jørgensen) represents another, more familiar, type of woman for whom the moral compass from which Karl has gradually distanced himself is still intact. She suggests that he sells his shares in the factory and their house. It is a pain to her that the family is breaking up, but her sympathy is with Aksel: “You can see how we push the boys away.” When an injured English pilot must be accompanied to Sweden, she offers her help as a trained nurse. The practical task solves her moral dilemma.

The film started with Karl and Eva’s silver wedding, spoilt by German airplanes inaugurating the occupation. The harmonious family portrait brought over by a Swedish relative on that occasion is later seen hanging on the wall in one of tastefully decorated living rooms. As the family members make opposing choices, the harmony is shattered into pieces. Only the painting reminds us of the past. It may seem contrived and schematic that all opinions are represented in the same family. However, it epitomizes the drama that the conflicts and clashes of the big story are visualized in the small family universe. Just like in Matador, where the small story also reflects the big one, it helps to paint the Skov family as a picture of the whole of Danmark.

Conclusion

Danish occupation films have functioned as a persistent transmission mechanism between history and society. With great intensity and energy and from many different perspectives, the films have processed trauma and identity issues since 1945. Through films, mythical interpretations of the events during the occupation have been produced, and through films they have been denied. The history of the freedom fighters has been confronted with the history of the marginalized. You understand the main features of the development of the occupation films better if you include the historiography. But occupation films cannot be reduced to being illustrative examples of historiography.

The occupation films follow the development in historiography in the sense that some of the films from 1945 to the 1960s are characterized by the consensus concept, while different types of critical-investigative approaches set in later. But this is not a linear development. Whereas the conflict concept was strong in historiography for a period, in the occupation films it was first mixed with the marginalization perspective and then included in the cinematic synthesis efforts in Matador, Badehotellet and De forbandede år. The uneven chronological development is emphasized by the fact that it is difficult to find a more critical film than Tre Aar efter from 1948.

Occupation films were based on the genre of resistance but have since expanded and varied the points of view by using subgenres as diverse as film comedy, childhood film, films thematizing the marginalized, escape films (about the Jews’ flight to Sweden), the biopic and the synthesis film. Through different tonalities, it has provided different answers to the why of resistance, delivering images of victims and executioners, freedom fighters and collaborationists, war and peace, and notions of national identity. For the next generations to come, the representations of fiction will only become more important because the contemporary witnesses have long since died.

Notes

1. In the following, all translations of Danish quotations are mine. Film titles are consistent with the English titles provided by DFI. Where individual films do not have English language titles, I have used the Danish ones.

2. The resistance movement used the term ‘likvidering’ signifying an unofficial execution of a traitor or an informer (‘stikker’) by members of the resistance. In lack of a precise equivalent in English, I have chosen the same term, liquidation, combined with single quotation marks.

3. SOE, established in 1940, was a British organisation coordinating resistance and sabotage in the occupied countries.

References

Agger, Gunhild Moltesen (2025). Lange skygger. Besættelsen i film og serier. København/Aarhus, Nord Academic.

Agger, Gunhild Moltesen (2024). ”Danske landsforrædere på film”. In: Unni Langås og Henrik Torjusen (red.). Krigsforbrytere i dagens estetiske minnekultur. Oslo, Cappelen Damm.

Bondebjerg, Ib (2023). Film, historie og erindring. Hellerup, Spring.

Bondebjerg, Ib (2005). Filmen og det moderne. Filmgenrer og filmkultur i Danmark 1940-1972. København, Gyldendal.

Bryld, Claus og Warring, Anette (1998). Besættelsestiden som kollektiv erindring. Historie og traditionsforvaltning af krig og besættelse 1945-1997. Frederiksberg, Roskilde Universitetsforlag.

Burke, Wendy (2017). Images of Occupation in Dutch Film. Memory, Myth and the Cultural Legacy of War. Amsterdam, Amsterdam University Press.

Calum, Per. ”Der var engang en krig”. In: Jyllands-Posten 30/1 1966.

Christensen, Claus Bundgaard; Lund, Joachim; Olesen, Niels Wium og Sørensen, Jakob (2015). Danmark besat. Krig og hverdag 1940-45. København, Informations Forlag.

Hewitt, Leah D. (2008). Remembering the Occupation in French Film. Houndsmills, Palgrave Macmillan.

Iversen, Gunnar (2021). “Acts of Remembering: Audiovisual Memory and the New Norwegian Occupation Drama”. In: Marianne Stecher-Hansen (ed.): Nordic War Stories: The Second World War as Fiction, Film, and History. New York, Berghahn Books.

Iversen, Gunnar (2018). ”New Enemies, New Cold Wars: Reimagining Occupation and Military Conflict in Norway”. The Enemy in Contemporary Film. Martin Lschnigg, and Marzena Sokoowska-Pary (eds.), Walter de Gruyter GmbH.

Iversen, Gunnar (2012). “From trauma to heroism: Cultural memory and remembrance in Norwegian occupation dramas, 1946-2009”. In: Journal of Scandinavian Cinema, vol. 2, no 3.

Jensen, John V. (2025). ”Landminer ved Vestkysten 1943-2012.” In: Lex.dk.

Kirchhoff, Hans (2004). ”Oversigt. Besættelsestidens historie – forsøg på en status”. In: Historisk tidsskrift bind 104, hæfte 1. København, Den Danske Historiske Forening.

Kristiansen, Tom (2021). “The Norwegian War Experience: Occupied and Allied”. In: Marianne Stecher-Hansen (red.). Nordic War Stories: The Second World War as Fiction, Film, and History. New York, Berghahn Books.

Langkjær, Birger (2012). Realismen i dansk film. Frederiksberg, Samfundslitteratur.

Molin, Liva Johanne Ehler (2016). ”Besættelsesfilm lærer os mere om aktuelle kriser end om fortiden.” In: Information 28/10.

Monggaard, Christian (2025). ”Danske film om Besættelsen har bevæget sig fra helteportræt til udforskning af mørke hjørner.” In: Information 2/5.

Monggaard, Christian (2020). ”De kæmper hver deres kamp for at komme igennem Besættelsen uden tab af ære eller liv”. In: Information 3/1.

Neergaard, Ebbe (1960). Historien om dansk film. København, Gyldendal.

Nissen, Dan (1980). ”Modstandskampen på film”. In: Anders Troelsen (red.). Levende billeder af Danmark. København, Medusa.

Olesen, Niels Wium (2012). ”Besættelsestiden i eftertidens lys”. Danmarkshistorien.dk

Petersen, Brian (2015). Johan Jacobsen. Mod strømmen i dansk film- og produktionskultur. Ph.d.-afhandling. København, Det humanistiske Fakultet.

Stage, Jan (1966). ”Var der engang en krig?” In: Land og Folk 6/7.

Stecher-Hansen, Marianne (2021). “The War Film as Cultural Memory in Denmark”. In: Marianne Stecher-Hansen (red.). Nordic War Stories: The Second World War as Fiction, Film, and History. New York, Berghahn Books.

Tamm, Ditlev (2010). ”Retsopgøret i Danmark”. In: Hans Fredrik Dahl, Hans Kirchoff, Joachim Lund og Lars-Erik Vaale (red.). Danske tilstande – norske tilstande. København, Gyldendal.

Villadsen, Ebbe (2000). ”Besættelsesbilleder. Den tyske okkupation i danske spillefilm“. In: Kosmorama # 226. København, DFI.

Suggested citation

Agger, Gunhild Moltesen (2026), The ambivalence of occupation - Danish occupation films 1945-2023. Kosmorama #290 (www.kosmorama.org).