Introduction

One of the cupboards in the Dreyer Archive at the DFI contains a collection of some sixty books on Mary, Queen of Scots (1542-1587) and on the history of Scotland – testimony to the director’s painstaking research for a film he was never able to make. In common with his unrealised film projects on Jesus and on Medea, the latter filmed by Lars von Trier for Danish television in 1988, Carl Th. Dreyer’s Maria Stuart reached an advanced stage of development. A screenplay of some 250 pages was written with his son, the journalist Erik Dreyer, and translated into English by Birgita Lindvad with the title Mary, Queen of Scots. Considerable quantities of Dreyer’s research materials for the film have survived, along with his collection of books on Mary Stuart and her times. These papers record two visits to Edinburgh, a decade apart – in 1946 and 1955 – during which Dreyer hunted through bookshops, visited historic sites, and discussed his ideas for the film with local contacts.

How would this unrealised film have looked, had it been made? Any reader willing to invest a few hours digesting the screenplay of what was conceived as a three-hour production will

find a wealth of clues. Character motivation and psychology, details of costume and set, indications of camera movement and shot length – all these are incorporated into the treatment. The original Danish text even contains English-language dialogue, where Dreyer was confident of the historical record or of his characters’ conversational style. We can also extrapolate from the extensive corpus of Dreyer’s own research materials preserved in his archive, and, of course, speculate on the basis of his experiments with setting and historical reconstruction throughout his career.

The purpose of this article, however, is not to mourn the fact that this film was never committed to celluloid, but to engage with the traces and stages of the filmmaking process preserved in the archive. The aim is twofold: first, to make use of the archival materials pertaining to Maria Stuart to re-trace Dreyer’s steps as he researches the life of one of his historical heroines; and second, in doing so, to enrich our understanding of Dreyer’s approach to the mediation of the historical record on film. In the case of Maria Stuart, Dreyer seems to have accumulated an impressive knowledge of not only the historical facts of the queen’s life but also the associated historiographical controversies. However, I will suggest that the screenplay ultimately traduces this knowledge in the service of psychological realism, constructing a problematically passionate Mary whose fate turns on a set of letters and sonnets she may or may not have authored.

The historical Mary, Queen of Scots

Mary Stuart was born on 8 December 1542, and was crowned Queen of Scots as an infant, her father, James V, having died a week after her birth. [1] Her mother, Mary of Guise, was of French descent and the young Mary therefore grew up in France, where she married the dauphin François in 1558. He died just a year after his ascension to the French throne, and the beautiful young widow travelled to Scotland in 1561. The Catholic queen arrived amid an escalating political and religious crisis, the Scottish Reformation, and her Council was dominated by protestant Lords. Mary’s cousin, Elizabeth I of England, was childless, and Mary’s potential claim to the English throne rendered her a dangerous rival. In 1565 Mary fell in love with and married another cousin, Lord Darnley. Their son James, later King James VI of Scotland and James I of England, was born the next year, but the marriage was unhappy, and Darnley died in mysterious circumstances. Mary married again almost immediately, this time with Lord Bothwell, her second husband’s assumed murderer. Whether and how Mary was actively involved in the murder plot has been the subject of controversy amongst historians; the discovery of a bundle of letters and poems in a silver casket (the so-called Casket Letters and Sonnets) in the summer of 1567 was enough to implicate her. She abdicated and was imprisoned, first by her enemies in Scotland, and later in a series of English castles by Queen Elizabeth. In 1587, after two decades as a prisoner, Mary was executed (cf.National Museums of Scotland).

Dreyer in London, 1946

In the immediate post-war period, Danish film was all the rage amongst British film connoisseurs. By 1947, the Scottish film pioneer Forsyth Hardy (1947b) could write that Denmark’s documentary production ‘would not shame a country six times its size’, and the English documentarist Paul Rotha declared himself very impressed by Denmark’s wonderful directors (Kn. P. 1947). Documentary filmmaking in Denmark had undergone an intense period of development during the German Occupation of the country (1940-45). As Hardy explained to his readers, the existing educational film agency Dansk Kulturfilm had been complemented and consolidated from 1941 by the Danish Government Film Committee, Ministeriernes Filmudvalg, under the leadership of Mogens Skot-Hansen. Hardy pays the work of these agencies the ultimate compliment; for him, the body of films made during wartime to promote Danish industry and social cohesion had done for Denmark ‘what the G.P.O. Film Unit under John Grierson had done for Britain’ (Hardy 1947b).[2] Immediately after the Liberation, arrangements were made through Skot-Hansen to bring the leading G.P.O. Film Unit figure Arthur Elton to Denmark. His task was to advise on the production of a series of films in English about Danish social security for export abroad – an exercise in nation-branding.

But Elton’s involvement on the Danish film scene put Dreyer in an awkward position. Dreyer wrote to Mogens Skot-Hansen to explain that he did not wish to meet Arthur Elton in Copenhagen. Dreyer had, he said, a guilty conscience about Elton because he knew that the Englishman wanted to tempt him over to London to make films there, whereas Dreyer had his sights set on America (Dreyer 1945). Dreyer had been writing and directing short films for the Government Film Committee since 1942, and was quickly co-opted into collaborating on the series Social Denmark; to have Dreyer’s name associated with a short film was to improve its chances of circulation abroad. His wartime short film Mødrehjælpen (Good Mothers, 1942) was relaunched as one of five Social Denmark films, and he also wrote the manuscript for a new film on pensions, The Seventh Age (1947). As Kimergård (1992: 49) has trenchantly observed, Dreyer’s short films have an air of tedium about them; Elton, too, eventually became exasperated over Dreyer’s apparent lack of focus in developing the manuscript for The Seventh Age, critiquing his tendency to weigh the story down with tedious detail rather than deploying his exceptional talent for depicting the experience of old people (Elton 1946).

Along the way, the choice of which side of the Atlantic to prioritise was temporarily settled by the success of the premiere and subsequent run of Vredens Dag (Day of Wrath, 1943) in London. The film opened at the Academy Theatre on 24 November 1946 to a rapt and unusually quiet audience (Filmjournalen 1947: 8). In London for the premiere, Dreyer himself moved through the city ‘unheralded and unnoticed’, lamented the critic Joan Lester (1946), describing him as ‘a slim, fair, elderly Scandinavian with a sensitive, clean-shaven face and diffident manner’. To Dreyer’s delight, the premiere attracted not only an intellectual elite but also ordinary people, who, he commented to one interviewer, sat as quietly as if they were in a real theatre (Poulsen 1946). While the reception of Day of Wrath at its 1943 premiere in Copenhagen had dismissed the film as a relic of the silent era (Gtz 1943), the film’s critical and popular success in London was instrumental in opening up an opportunity for Dreyer to work in the UK.

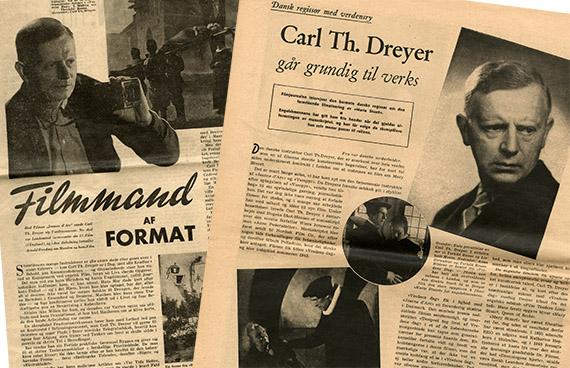

Clippings from Filmjournalen and Ude & Hjemme (February 1947) about Dreyer and Maria Stuart. (DFI - The Dreyer Collection).

Dreyer himself claimed to an interviewer in the Danish daily Nationaltidende (Poulsen 1946) that he was now working on the script for Maria Stuart on the back of the success of Day of Wrath. The Norwegian magazine Filmjournalen states unequivocally that the success of Day of Wrath in London was the ‘direct cause’ of Dreyer’s short-lived contract with the company Film Traders Ltd. (Filmjournalen 1947: 8); in fact, Film Traders was a distribution company supplying foreign films to the Academy theatre (where Day of Wrath had been shown) and had not yet produced a film (Koch-Olsen 1949). Dreyer explains to the Filmjournalen interviewer that Film Traders Limited had asked him to choose a subject from history for his first film with the company, and he suggested Mary Stuart, whose story he had always wanted to adapt for the screen (Filmjournalen 1947: 23). British interest in Dreyer was itself a subject of satire in the Danish press; one article tells us just as much about the operation of the famous Law of Jante in the face of the overseas success of a native as it does about the aspects of British culture known to Danes at the time:

"Dreyer has specified a few other conditions for his involvement [in filming Mary, Queen of Scots]. There mustn’t be any fog during his visit, and no football or cricket results in the newspapers, as those sports do not interest him. In anticipation of the battle scenes in the film, he has requested that the Scots undertake an armed uprising, and he has requested that George Bernard Shaw not be allowed to make fun of him." (Social-Demokraten, n.d.) [3]

Dreyer in Scotland, 1946

His reputation blossoming in Britain, Dreyer took the opportunity to make a ‘flying visit’ to Scotland (Hardy 1947a: 3) after the premiere of Day of Wrath. A couple of months later, at the end of January 1947, Forsyth Hardy devoted his radio programme ‘Arts Review’ on the Scottish Home Service to a discussion of Dreyer’s work and his recent visit. The programme coincided with Day of Wrath’s run at the Cosmo cinema in Glasgow and a screening at the Edinburgh Film Guild, and Hardy encouraged his listeners to see the film, adding: ‘I know of no other director working today who can achieve such an intensity of feeling in a film, such a sense of active sharing in the drama’ (2). Hardy’s account of his two days with Dreyer in Edinburgh the previous November gives a vivid sense of Dreyer’s absorption in the Maria Stuart project:

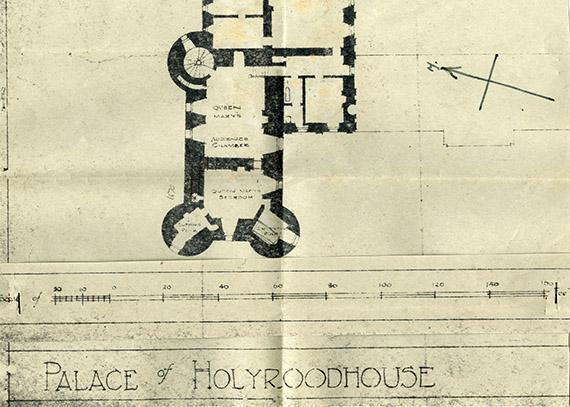

"He could think and speak of nothing else. Indeed, there were occasions when his absorption was a little embarrassing. While sitting in the hotel, for example, his attention would suddenly become focused on someone several tables away, someone with features which suggested a train of thought: could he play Bothwell (or Darnley or Rizzio) and how would he look in the costume of the period? Could he grow a convincing beard? [. . .] Dreyer visited Holyrood and Borthwick Castle, studied plans and made notes on interior decoration, dug himself ever deeper into the period. The idea of a film on Mary Stuart has been germinating in his mind for a long time, perhaps since a visit he paid to Edinburgh about 1936. On that occasion, I remember, he sat silent and withdrawn, pondering some deep problem. What a contrast on his recent visit! About Mary Stuart he would talk, and did, all day and far into the night, stopping only to study a plan or record another impression in a crowded notebook" (Hardy 1947a: 3-4)

As a leading figure on the Scottish film scene, Hardy was keen to promote the idea of a renowned auteur making a film in Scotland. In the same radio programme, he commented: ‘Here is an opportunity for an outstanding film to be made in Scotland. It isn’t likely to occur often and we must not lose it.’ (Forsyth Hardy, 1947a: 4).

The contract with Film Traders fell through, though not before Dreyer had submitted a manuscript that was ‘perfect, but too expensive’ (Drum and Drum 2000: 207) – the screenplay discussed later in this article. While seeking out sponsors for his feature film projects, Dreyer continued to make state-sponsored short films that helped him put food on the table – and which, not incidentally, also sustained his connection with Scotland. Several of his shorts were screened at the burgeoning Edinburgh International Film Festival (EIFF), which, in its earliest incarnation, from 1947, was a specialist documentary festival. Denmark was well represented at the EIFF in its first decade, and Dreyer’s short films were among the first wave of Danish films to be shown there. In 1948, Dreyer’s Landsbykirken (The Danish Village Church, 1947) and De nåede Færgen (They Caught the Ferry, 1948) were reviewed as examples of Dreyer’s skilled craftsmanship’ and as ‘stamped with the quality of his visual imagination’ (Hardy 1948: 16).

Other Danish filmmakers clamoured to visit Edinburgh. In 1949, for example, the Danish delegation encompassed Ebbe Neergaard, head of Statens Filmcentral (the national film distribution centre), as well as the established documentarists Theodor Christensen and Søren Melson. They were joined by the young filmmakers Ove Sevel, Jørgen Roos, Nic. Lichtenberg and Erik Witte, who had driven all the way from Copenhagen via London in a tiny car flying a yellow pennant emblazoned with ‘Danish Documentary’ (Sevel 2006: 46-7). That same year, 1949, Dreyer’s new short film Thorvaldsen was shown at the festival, and dismissed as ‘somewhat static’ by Hardy (1949: 18). A year later, with Storstrømsbroen (The Storstrom Bridge, 1950), observed the Daily Dispatch, ‘Dreyer [went] all lyrical’, while The Scotsman grumbled: ‘Nothing is explained. The director is content to look delightedly at his subject and praise it with his camera’ (EIFF 1950: 4). Nevertheless, these short films kept Dreyer’s name on the British film festival circuit in the decade between the UK premieres of Day of Wrath and Ordet(The Word, 1955).

In Scotland again, 1955

Dreyer’s financial woes were alleviated in 1952, when he was awarded the directorship of the Dagmar cinema. The film company Palladium adopted his feature film project Ordet. And by the middle of the decade Dreyer again found himself in Edinburgh, as an honoured guest. This time, he had been invited to hold a lecture at the EIFF by the British Film Institute (Quinn 1955). While Dreyer initially demurred, citing filmmaking commitments (Dreyer 1955a), he wrote again in late July to say that his plans had changed and that he would like to ‘seize the opportunity of [his] stay in Edinburgh to do some research-work for a film on Mary Stuart’ (Dreyer 1955b).

Dreyer’s lecture took place on Tuesday, August 30 1955 at 11 am, at the Cameo Cinema in the Tollcross area just west of the city centre (Poole 1955) – a cinema which still exists today. His lecture tackled the issue of colour in film, and was described as ‘challenging’ in the magazine Film Forum. An abridged version of the lecture was published in the Danish newspaper Politiken on the day the lecture was delivered in Edinburgh, under the title ‘Fantasi og farve’. [4] In this text, Dreyer argues that colour offers the best chance for renewal of cinema through abstraction, potentially allowing filmmakers to lift film out of the embrace of photographic naturalism. He goes so far as to suggest that colour could supersede perspective, implicitly arguing for a haptic filmmaking practice that might return film to the condition of painting. It is exciting to imagine how this playful and yet serious approach to colour might have informed Maria Stuart, if, as the Danish press reported on his return in late September, he was seeking to make the Scottish film in colour and Cinemascope (Loup 1955: 30).

Dreyer’s correspondence during and after his stay in Edinburgh indicates that he left Edinburgh for London on September 6, giving him almost a whole week for his ‘research-work’ on Maria Stuart(Dreyer 1955c; Davis 1955). As we shall see presently, the materials he gathered on this trip indicate that he visited Stirling castle as well as a number of museums in Edinburgh. Having thus encountered first-hand the historic sites where Mary, Queen of Scots lived out the life he so passionately wished to portray, it must have been especially galling for Dreyer to receive a letter of September 2 forwarded by his secretary at the Dagmar Cinema, informing him that the Fox Film Company was not interested in Maria Stuart (Westermann 1955). On the bright side, Dreyer had scheduled a meeting for September 6 in London to discuss his Jesus film with his ever-elusive American agent Blevins Davis. The meeting prompted him to return to Copenhagen immediately, thus missing out on the opportunity to meet James Quinn, the Director of the British Film Institute, who had invited him to Edinburgh (Dreyer 1955c). Mid-1956 saw a spark of interest from Robert L. Cohn at Columbia pictures in London; Dreyer intended to return to Edinburgh for some final research then complete the screenplay, if only he could secure ‘the moral and economic support of a leading film company’ (Malmström 1956).

And so the dance continued, more books were bought, more expressions of interest and offers of funding fell through, and the possibility of filming Maria Stuart remained forever just out of reach on the horizon, tantalising Dreyer and those who loved his work. Until, that is, Dreyer reached the end of his life in 1968 – and, as Forsyth Hardy had warned twenty years earlier, the opportunity for this ‘outstanding film to be made in Scotland’ was irretrievably lost.

Earlier films about Mary, Queen of Scots

The persistent interest amongst critics and cinephiles in Dreyer’s Maria Stuart project is testament to the enduring fascination exerted by the tragic queen, and to the filmmaker’s reputation as a serious director of historical cinema. Before going on to look at Dreyer’s work on this film project in more depth, it is worth reviewing what contemporary commentators anticipated from a film by this particular director about this particular queen.

To propose a film about Mary, Queen of Scots was neither unheard-of nor uncontroversial. The 1920s had seen a spate of films about the Scottish monarch and her cousin Queen Elizabeth I of England (Aziza 1997: 365-6). These included Rudolf Dworsky’s Marie Stuart (1921), The Loves of Mary, Queen of Scots (Denison Clift, 1923), J. Stuart Blackton’s The Virgin Queen (also 1923), Marie Stuart (dir. Friedrich Feher and Leopold Jessner, 1927), and Sacha Guitry’s Les Perles de la Couronne (1927). [5]

In particular, two other film adaptations of the queen’s life were fresh in the memory of post-war audiences and reviewers. John Ford’s 1936 Hollywood production, Mary of Scotland, starred Katharine Hepburn in a heavily embroidered biopic that incensed Scottish reviewers (Hardy 1947b: 1). More recently, the powerful Nazi film director and Head of Production at Ufa, Carl Froelich, had made Das Herz der Königin (The Heart of the Queen) in 1940. This film was a vehicle for the star Zarah Leander, and constructed the notion of the Scottish queen’s ‘heart’ as antithetical to the cold efficacy of her English contemporary and nemesis, Elizabeth I.

Zarah Leander in Das Hertz der Königin (Carl Froelich, DE, 1940) and Katharine Hepburn in Mary of Scotland(John Ford, US 1936) as Mary Stuart. (DFI Stills & Posters Archive).

The contrast between Ufa’s and Dreyer’s approach to historical detail was not lost on the press when Dreyer’s plans for his Maria Stuart film became public knowledge in 1946; Froelich’s and Ford’s films are repeatedly held up as an example of the kind of film Dreyer would not be making. The Norwegian Filmjournalen, for example, framed its expectations for Maria Stuart by contrasting La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc (Dreyer 1928) with Ford’s and Froelich’s overwhelming masses of extras and elaborate sets:

"He will set about the film with the greatest of respect for Mary Stuart, this proud Scottish queen, who dared to defy England’s all-powerful Queen Elizabeth. And as Dreyer can construct his film according to his own artistic convictions, there is no doubt that his work will be a landmark in film history" (Filmjournalen 1947: 8, 23)

By chance, the Danish author Karen Blixen (Isak Dinesen) visited Ufa studios during the shooting of Froelich’s film, and her wry description of the process provides a vivid impression of a set characterised by tawdry artifice. The Highland setting was conjured up, observes Blixen, by filming piles of sand planted with small pine trees from a low camera angle. Zarah Leander’s orange make-up, exaggerated eyelashes, and fake ermine and silk are a travesty of the queen’s reputed beauty. Blixen observes that Ufa’s decorators and handymen worked conscientiously to reproduce period detail, but that their craftsmanship belied the flimsiness of their material (Blixen 1992: 117-19). Blixen’s point is, of course, to reveal the Third Reich as staging without substance (119). However, the glimpse into Ufa’s studios she affords us does much to throw into sharp relief Dreyer’s own artisan construction of historical authenticity. Dreyer’s Mary would, like Froelich’s Mary as observed on set by Blixen, be a victim of the Zeitgeist’s compulsion to witness history repeating on screen, forced to re-live the most terrible events of her life again and again with each repeated take (118). But Dreyer’s queen would, at least, be re-enacting events reconstructed with the exactitude and nuance that only extensive research can yield – or so the critics seemed to expect.

Dreyer and Kracauer: The impossibility of the historical film

A notable contemporary commentary on Dreyer as director of historical films was provided by the German film theorist and cultural critic Siegfried Kracauer, published in 1960 in the anthology of his writings, Theory of Film: The Redemption of Physical Reality. Dreyer was the filmmaker who had come closest to accomplishing a task that Kracauer saw as fundamentally impossible: representing the past on film. For Kracauer, ‘the historian’s quest and history on the screen are at cross-purposes’ (1997: 80). With its futile attempts at authenticity of costume and setting, the historical film suffers from an ‘irrevocable staginess’ (77). This effect of ‘staginess’ is produced, he argues, by the viewer’s knowledge that the reconstructed milieu ends at the edge of the set; the bounded world of the historical film is anathema to cinema’s propensity to reveal the open ‘space-time continuum of the living’ (78). These remarks about the inadequacies of the historical film anticipate Kracauer’s refined philosophy of the relationship between past and present, published posthumously in 1969 as History: The Last Things Before the Last. In his Theory of Film, though, Kracauer’s insistence that historical representation is ‘hardly compatible with a medium which gravitates towards the veracious representation of the external world’ (79) is rooted in his preoccupation with film as a twentieth-century technology for the recording of material reality. As Miriam Bratu Hansen puts it, history ‘disappears’ in Kracauer’s Theory of Film, insofar as ‘the specifically modern(ist) moment of film and cinema is transmuted into a medium-specific affinity with physical, external, or visible reality’ (Hansen 1997: xiii).

However, in Theory of Film, Kracauer does linger on the problem of the historical film long enough to consider two possible strategies for filmmakers aspiring to mitigate the incompatibility between cinematic medium and historical record. He chooses to exemplify each of these strategies with reference to films by Dreyer: La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc (1928), and Day of Wrath.

Kracauer’s ‘camera-reality’

In the case of Dreyer’s film about Joan of Arc, he has, thinks Kracauer, chosen ‘to shift the emphasis from history proper to camera-reality’ (Kracauer 1997: 79). ‘Camera-reality’ is one of the terms used in Kracauer’s book to emphasise what the camera records: ‘actually existing physical reality– the transitory world we live in’ (28). The film’s unrelenting focus on faces, especially Joan’s, partially solves the issue of ‘staginess’, but creates two other problems, he argues. First, a tension arises between the documentary-style attention to faces and the occasional perspectives on the wider sets and ensembles, which appear more ‘stylized’ (79) in comparison. A second, more significant problem is the film’s neglect of ‘material phenomena which are no less contingent on the drama’ than the faces are (80). As a consequence, this film takes place in a kind of time-out-of-time.

Renée Falconetti as Jeanne d'Arc in The Passion of Joan of Arc (Carl Th. Dreyer, FR, 1928). (DFI Stills & Posters Archive).

Having nevertheless interpreted Dreyer’s Jeanne d’Arc as cinema’s most successful example of rendering history as camera-reality, Kracauer then turns to Day of Wrath as an example of a diametrically opposed strategy. In this case, he supposes that Dreyer’s aim is to depict ‘the modes of being peculiar to some other historical era’ (81). As cinema, for Kracauer, is a medium of modernity, only by aspiring to the condition of earlier forms of representation can a film transcend its own inability to capture the essence of an incompatible era. In the case of Day of Wrath, Dreyer is ‘apparently determined to convey late medieval mentality in all its dimensions’ and does so by echoing paintings of the period in his imagery (81). Kracauer sees this strategy as another form of documentary (82), in the sense that the film gestures to the modes of representation most germane to the lifeworld of the era in question, that is, documenting the period’s mediation of itself.

Dreyer’s ‘rhythm’

Kracauer’s comment that Dreyer aims to capture ‘the modes of being peculiar to some other historical era’ (81) is strikingly similar to Dreyer’s own defence of the ‘rhythm’ of Day of Wrath. In his well-known essay ‘A Little on Film Style’, originally published as a riposte to criticism of the slow pace of the film at its Danish premiere, he writes: ‘[i]t is the plot and the milieu in Day of Wrath that determines its broad, peaceful rhythm […] it expresses the slow pulse of the era’ (Dreyer 1959: 65, my emphasis). [6] Thus, while Kracauer (1997: 81) notes how the characters in Day of Wrath move slowly and maintain spatial distance from each other, thus typifying late a medieval ‘mode of being’, Dreyer explains how the appropriate rhythm of a film is the ‘pulse of the era’, which is established by the interdependence of, amongst other things, camera movement, editing, and bodies on screen (Dreyer 1959: 64). Both men are clearly interested in the idea that film’s possibilities (and limitations) regarding the representation of time, space and movement are not only medium-specific but also historically specific; cinema can only approach the mentality of another era by paying attention to its own technological and cultural contingency. [7] While Kracauer praises this quality in Day of Wrath, he has reservations about the more modern psychology of the characters (1997: 81). Though he makes this point in parentheses, it is the logical corollary of his insistence on cinema as a profoundly modern(ist) record of physical reality. After all, Dreyer’s vaunted psychological realism is a product of its own time. In ‘A Little on Film Style’, he asks: ‘And isn’t it true that the great dramas play out quietly? People hide their feelings and avoid showing on their faces the storms raging inside them’ (Dreyer 1959: 65). This is a compelling aspect of Dreyer’s style, but such behaviour is, arguably, historically and culturally contingent. How can a close-up of a face responding to some reconstructed sixteenth-century event produce anything other than an image of twentieth-century psychological realism?

From research to screenplay

If we now turn to Dreyer’s research methods for Maria Stuart, and his screenplay, we see traces of the strategy which Kracauer identified and admired in Day of Wrath. A commitment to capturing the ‘modes of being’ of Mary’s era is evident in Dreyer’s interest in the places in which the queen lived; in the spatial politics of court and the role of bodies in those politics, as sketched in the stage directions; and in the material culture of the day (artefacts, costumes, etc.). On the other hand, there are hints that the film would have included sequences of ‘camera-reality’ focusing on Mary’s face, à la Jeanne d’Arc. But Maria Stuart also shares with La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc a feature which Kracauer’s reading does not account for: a reliance on the written historical record.

Dreyer collects material

Back home from his trip to Britain in 1946, Dreyer proudly displayed his growing library on Mary, Queen of Scots to the Filmjournalen interviewer. The books fill a whole shelf in his study, and on the desk there is also a pile of hefty volumes, reports the journalist. But, says Dreyer, his collection is only a fraction of the literature available on Mary Stuart. He had seen a catalogue of all the international works on the subject, and the catalogue itself filled three volumes (Filmjournalen 1947: 23). It is noteworthy that although the archived screenplay for Maria Stuart dates from the late 1940s, Dreyer continued to read around the subject for at least another decade; he was in correspondence with British booksellers until at least 1958, including a Mr Chambers (Dreyer 1955e) in London, and John Grant on Edinburgh’s George IV Bridge, sometimes ordering cases full of antiquarian books at a time (Grant 1958). He also maintained records of relevant books available in Copenhagen’s Royal Library, and had lists of others yet to be sourced and read. He frequented Frederiksberg Library, too, over a period of ten years researching the film, and befriended the librarian there, as recounted by Jean and Dale Drum (2000: 206-07).

Aside from supplementing his library and his people-watching (as described by Hardy above), Dreyer used his time in Scotland to familiarise himself with the places where Mary, Queen of Scots lived and with the visual and material culture of the period. For example, during his mid-1950s visit, he apparently visited the National Museum of Antiquities of Scotland to study artefacts of the time; Robert B. Stevenson, the museum’s Keeper, wrote to Dreyer on 22 October 1955 thanking him for the gift of a book on Danish wall paintings, saying how glad he was ‘to be able to show you things here’ and offering help with the ‘Queen Mary’ film (112). A 1951 illustrated catalogue from the Scottish National Portrait Gallery (DI, B: 111) contains several relevant portraits, and Dreyer used cut-outs of portraits of the Reformation figures Martin Luther and John Calvin as bookmarks. He also kept postcards of John Knox’s house on the Royal Mile, the ruins of Holyrood chapel, and two classic portraits of Mary: the so-called Sheffield portrait (Cobham version), and the queen ‘en deuil blanc’ (in white mourning dress) (112-4). A handwritten note from the same trip indicates that Dreyer met the palace’s Sergeant Warden, a Mr Graham, at the front entrance of the Palace of Holyrood, the scene of many key events in the queen’s life (114). There is a tourist guide map and brochure to Stirling, suggesting that Dreyer travelled to Stirling Castle, where Mary was crowned Queen as a child and lived for part of her life. Indeed, distributed throughout the archive are a number of photographs, postcards and magazine clippings of British castles, as well as notes on interiors and exteriors.

Notes and index cards

The extensive collection of Dreyer’s preparatory notes on Maria Stuart that have survived in his archive at the DFI show how he used his books and other sources to develop ideas for plot, character, mise-en-scène, and sound. Key passages from the texts were typed or hand-copied onto index cards and colour-coded slips of paper, organised both by the film’s five Acts and in themed bundles covering such topics as Scottish poetry, dance and music, furniture and clothing in Mary Stuart’s time, and the city of Edinburgh. He seems to have developed the character of John Knox in particularly painstaking detail using this method, though Knox has a very minor role in the extant screenplay. In this case and in others where the notes deviate from the content of the manuscript, it is not clear whether the notes pre- or post-date the 1940s screenplay. However, this system of note-taking on slips of paper that could be sorted and re-ordered as required seems to have been a long-standing method of Dreyer’s. For example, the Italian journalist Ernesto Quadrone describes how the director used a similar system to absorb information while they collaborated on a production in Africa in the 1930s:

"From the first moment I had enjoyed how Dreyer asked about everything I told him about Africa, and wanted me to expand on everything and try to get at the core of it. He ‘rifled’ curiously through what I knew, as though he was trying to get to know the whole continent. He wrote down all my answers to his numerous questions on little bits of paper, which he would then read through and examine, and then he would start to quiz me again on some detail or other that he hadn’t quite understood, a sentence, a word, a colour, a sound, the tone of a voice that I hadn’t described carefully or precisely enough. The number of little slips of paper grew and grew, multiplying many times, ten-fold, a hundred-fold." (Quadrone 1951)

In this sense, as in others, Dreyer’s research work for Maria Stuart parallels his preparation for his better-known film project on Jesus.

Rhythm and space in the screenplay

While we cannot know how the notes from the 1955 visit would have influenced an eventual film, there are very clear instances in the 1940s screenplay where historical pedagogy (or at least convention) and Dreyer’s own personal observation feed into the text via his notes. One very rich and – for this Scot at least – amusing passage comes early on in the screenplay, at a ball following Mary’s wedding to Darnley:

"The dance is a mask-dance called 'On Purpose' which Mary has brought with her from the French court. All the ladies wear masks and are in men's clothes. Instinctively one feels that this deep, rather perverse form for dance with its air of sensuality hardly suits the cumbersome Scots." (Dreyer and Dreyer 1947: 12-13)

Dreyer’s people-watching in Edinburgh in the company of Forsyth Hardy had evidently opened his eyes to the average stature of Scots, relative to the litheness and height afforded the young Queen Mary by her French heritage. Less impressionistic is the ingenious idea of dressing the queen in ‘tight-fitting breeches’ and staging a dance at a point in the narrative when the precariousness of her position as a queen and her husband’s sexual insecurity must be established. In fact, Dreyer is using historical fact for the purposes of characterisation here. Mary’s court was notorious for its masked balls, which served both as entertainment and as a form of performed diplomacy; some did feature cross-dressing, which the queen was said to have indulged in occasionally, though not at the wedding itself (Carpenter 2003: 218). The principle of rhythm explained in ‘A Little on Film Style’ is put into action here. The sense of place and era emanates from the movements of the bodies on screen, which in turn are grounded in painstaking historical research.

Another interesting sequence in the screenplay (Dreyer and Dreyer 1947: 101) deepens the viewer’s (or rather, reader’s) appreciation of the spatial politics of the court. In this case, Mary and the members of her Council are lodging at Craigmillar Castle near Edinburgh. The inception of a plot to end Darnley’s life is staged with a series of floor-level shots depicting the plotters’ slippers sneaking around the castle in the early morning. The detail of their plan is revealed in snatches of dialogue, but the secrecy of the plot is underlined by the lack of sound other than ‘the soft shoes’ shuffle and the rustle of gowns’ (106) – again, we note how rhythm and sound are part and parcel of the portrayal of the ‘mode of being’ of a royal court of the era. As more of the Lords become involved, we see their feet moving from room to room, mapping the space of the castle, until ‘ten feet arrive at the door of the Queen’s room’ (107). While Mary’s acquiescence to the liquidation of her husband is left carefully unarticulated, her implication is powerfully signalled by the description of a shot in which she, literally, follows in the footsteps of her Council:

"Mary’s room. There is a picture at floor level, and all we see are Mary’s slippers lying in front of her bed – they also are list shoes – like the men’s. Then we see Mary’s legs coming out of the bed and into the slippers, and we have an idea that she puts on a wrap. We follow the feet across the floor." (110-11)

From sonnets to psychological realism

Dreyer was sufficiently well-versed in the literature to form opinions on historical controversies. To one bookseller, he writes that he is not interested in buying a particular text because he does not believe in the ‘genuinity [sic] of the Casket letters’ (Dreyer 1955d), that is, a set of letters which may have been falsified to implicate Mary in the murder of her second husband, Lord Darnley. In 1567, the summer Mary was deposed, the letters were, purportedly, discovered hidden in a silver casket with marriage contracts and a series of sonnets she had written about her love for Bothwell. Dreyer’s collection contains various editions of, and commentaries on, the casket documents. Notably, he had acquired a 1721 edition of George Buchanan’s 1571 compilation of the documents with commentary, the (anglicized) title of which is indicative of their status as a ‘true-crime’ publication of their day (Smith 2012: 153): A Detection of the Actions of Mary Queen of Scots, concerning the Murder of her Husband, and her Conspiracy, Adultery, and Pretended Marriage with Earl Bothwell; and a Defence of the True Lords, Maintainers of the King’s Majesty’s Action and Authority. Buchanan’s influential publication frames the letters and sonnets as evidence of Mary’s ‘character of excess, intemperance, and inordinate love’ (Smith 2012: 156). This construction of Mary’s temperament has been exploited by different historiographical agendas in different periods, as outlined by Smith; for example, she was advanced as an exemplar of feminine sensibility in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries (164-5), and co-opted by nineteenth-century debates on the unsuitability of women for political power (166); an example of the latter is Hugh Campbell, whose 1824 book The Love Letters of Mary Queen of Scots to James Earl of Bothwell with her Love Sonnets and Marriage Contracts is in Dreyer’s collection. By the early twentieth century, Smith detects a new tendency to assess Mary’s writings as literature, rather than as evidence of guilt (169). Typical of this trend was a book also in Dreyer’s library, Clifford Bax’s The Silver Casket, newly published in 1946 and thus contemporaneous with the extant screenplay.

Overall, Dreyer’s library contains a representative selection of editions and commentaries from three centuries of Marian scholarship. Whatever his mid-1950s views on the attribution of the Casket Letters and Sonnets, the 1940s screenplay leaves no room for doubt as to the queen’s passionate nature, nor her involvement in the murder of Darnley, though her acquiescence to the crime is grounded in a mixture of pragmatism and desire for Bothwell. Thus, Mary is appropriated by the filmmaker to suit the sensibility of the times, just as she had been by successive generations of historians. Also indicative of Dreyer’s privileging of the queen’s passionate nature is his decision to limit the film’s focus to the two-year period of the queen’s life in which she made two ill-starred marriages. The film opens with her marriage to her second husband, Darnley, in summer 1565, and narrates events (taking some artistic liberties in terms of their chronology) through to her incarceration at the hands of her third husband, Bothwell, in summer 1567. Though the screenplay ends with her execution, it skips over her abdication and two decades of exile in a series of English castles, just as it ignores her early life in France as dauphine and Queen Consort to her first husband, François II. Dreyer’s screenplay, then, is blatantly uninterested in Mary as a political figure, except insofar as the novelty of her royal status and the intrigues of her Privy Council can intensify its portrait of her as an unusually passionate woman. We might even speculate that the grasp of historical detail which would, no doubt, have been evident in the film’s mise-en-scène would have served as backdrop to a thoroughly modern melodrama.

Mary’s passion for Bothwell is ignited in a scene which, had it been filmed as described, would today probably have been considered more politically problematic than aesthetically ground-breaking. The historical record is ambivalent as to whether Mary married Bothwell because he had raped her, or because she had fallen in love with him. Dreyer combines both these ideas in a sequence which begins as an attempted rape and turns into a night of lovemaking illuminated by lightning and thunder. The next morning, Mary cries with joy, declaring that her life is just beginning (Dreyer and Dreyer 1947: 73-77). During the crucial transition from resistance to consent, the screenplay specifies that: ‘From now on we follow her in gliding close-ups. In her face the following scene is pictured as if in a mirror. From her reactions we guess Bothwell’s’ (72). By the next page, Bothwell’s back has obscured Mary’s face, and it is through her hands that we see (read) that she is submitting to her passion for him, first hitting and scratching, then caressing. This pivotal scene, then, is conceived in what Kracauer calls ‘camera-reality’ style, enabling the viewer (reader) to share this moment of intense psychological transformation with the queen. The historical context is excised from the picture, and the passion to which Mary’s own poetry gives expression blots out the nuances of the historical record, just as Bothwell’s ‘broad back […] covers her completely’ in the frame (73).

Staging the written record

For comparison, La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc opens with images of the trial record produced by the illiterate saint’s male judges, and thus pits (hand-)written history against the ‘camera-reality’ of her facial responses to the events (interestingly, the explicit staging of the trial document is not mentioned by Kracauer in his discussion of this film as a kind of documentary). Maria Stuart also takes the written word as an implicit intertext: the Casket Letters and Sonnets purportedly authored by the queen herself, but which may have been forged, doctored or mistranslated by her enemies (see Smith 2012). However, the extant screenplay does not indicate that the letters are to be visually flagged in any way. Though we see the imprisoned Mary ask for pen and ink, they are only mentioned in passing by Lord Melville towards the end of the manuscript: ‘We have found your letters to Bothwell […] one of them shows, that you knew Darnley was to be murdered’ (200).

The tension between the screenplay and Dreyer’s later comment about his scepticism regarding the authenticity of the Casket Letters begs some obvious questions. Did Dreyer craft the screenplay and Mary’s character to maximise the romantic or melodramatic impact of the film, despite believing in her innocence? Or did he feel that the Casket Letters, despite being forged, nevertheless gave expression to a plausible psychology or set of motivations? Either way, did his opinion on the status of the letters change between the completion of the screenplay and the 1955 note to the Edinburgh bookseller? There is no way to know for sure; we can only echo Jean and Dale Drum’s wistful observation about Dreyer’s research material for his Jesus film:

"this mass of material raises many tantalizing questions and answers very few of them. There are hundreds of photographs, presumably all made because they suggested something of line, texture, or style. But without Dreyer’s comments, it is not impossible to know what aspect of each item fascinated him or how he planned to use it. To add to the challenge, it is almost certain, since these items represented work over so long a period of time, that many of his ideas changed, yet there is no way of knowing which of the items is outdated and which he might still have been considering using." (Drum and Drum 2000: 293-4)

It is particularly tantalising to speculate how the Maria Stuart manuscript – crystallising at a relatively early stage of the research process due to the need to produce a screenplay for Film Traders – might have been revised in the context of a real-life production scenario, and in light of Dreyer’s evolving knowledge of the queen’s life.

Concluding remarks

What can we conclude about a film project that never reached its intended conclusion – to be committed to celluloid? Can we accept as a readable text in its own right the hundred-fold slips of paper, the shelves of books, the experience of landscapes, museums and castles, the translation of accumulated knowledge into a pro tempore screenplay? What the archive can reveal of Dreyer’s Maria Stuart is limited to the verbal, not the visual, but Maria Stuart can tell us something about the archive itself, and perhaps about the historical film.

In following Dreyer’s journeyings back and forth across the North Sea and through Mary Stuart’s biography, we come to realise how fragmented is the historical record, and how heavily embroidered is the narrative of any historical personage. In Carolyn Steedman’s words: ‘You know perfectly well that despite the infinite heaps of things they recorded, the notes and traces that these people left behind, it is in fact, practically nothing at all. There is the great, brown, slow-moving strandless river of Everything, and then there is its tiny flotsam that has ended up in the record office you are working in’ (Steedman 2001: 1165). Just as Dreyer fleshed out the psychology of his heroine to breathe life into the dry and fragmented historical record, only an act of the imagination can animate the remnants of his film that are left to us as typescript and scraps of paper.

Kracauer admires Dreyer’s Day of Wrath as a film that almost avoids ‘a violation of the historical truth’ (Kracauer 1997: 81). The film does so, he thinks, by aspiring to the condition of late medieval painting, disavowing its own twentieth-century technology of representation. If we indulge Kracauer’s conviction that cinema is not a proper medium for the depiction of past history, then the un-filmed film is the epitome of that logic. Dreyer’s Mary, Queen of Scots, whose passion and innocence turn on the authenticity of a casket of letters, can only be authentic on paper, not film.

BY: C. CLAIRE THOMSON / SENIOR LECTURER IN SCANDINAVIAN FILM / DEPARTMENT OF SCANDINAVIAN STUDIES / UNIVERSITY COLLEGE LONDON

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Lisbeth Richter-Larsen and Birgit Granhøj Dam for sharing their encyclopaedic knowledge of the contents of the DFI’s Dreyer Archive; Marc David Jacobs for sourcing invaluable materials in Edinburgh and enabling me to access the Edinburgh Film Guild archive; Lars-Martin Sørensen for providing key information on WWII cinema and alerting me to Blixen’s account of her visit to Ufa; and Henrik Fuglsang and colleagues for organising the digitisation of English and Danish film manuscripts.

Notes

[1] For an authoritative and compelling account of the life of the queen, see Antonia Fraser’s Mary, Queen of Scots, first published 1969 (Fraser 2009). This paragraph is included in the article to give the reader a brief overview of the historical figure behind the film project. [Return]

[2] Hardy tells his readers that around 150 such films had been made in occupied Denmark. This figure seems over-inflated, and may include films made between the end of the war and Hardy’s visit to Copenhagen. Christian Alsted (1979: 20) specifies that thirty-six short films were produced by Ministeriernes Filmudvalg during the Occupation, and Lars-Martin Sørensen puts the total number of documentary and short films made in Denmark between 1940 and 1945 at ninety (Sørensen 2014: 339). [Return]

[3] All translations from Danish sources are my own. [Return]

[4] A version of the lecture was published in Sight & Sound under the title ‘Notes on My Craft’ (Dreyer 1956), and a transcript of the lecture was later published as ‘Imagination and Colour’ (Dreyer 1973: 174-186). Many thanks to Casper Tybjerg for this clarification. [Return]

[5] For a discussion of these films in the broader context of cinema depicting the Renaissance, see Aziza 1997. [Return]

[6] This is my own translation from the anthology of Dreyer’s writings Om Filmen (Dreyer 1959). The essay ‘Lidt om filmstil’ (‘A Little on Film Style’) is available in English translation in Dreyer in Double Reflection, edited and annotated by Donald Skoller (Dreyer 1973). However, a misprint in the 1973 translation renders the crucial phrase ‘at udtrykke epokens langsomme pulsslag’ (literally ‘to express the slow pulse of the era’) as ‘to underline the slow pulse of the ear’ (Dreyer 1973: 134, my emphasis). For a more extensive discussion of this misprint and Dreyer’s notion of rhythm, see Thomson 2015. [Return]

[7] Dreyer’s essay is not listed in Kracauer’s bibliography, but Ebbe Neergaard, Dreyer’s Danish biographer, does appear in some notes in the book. It seems reasonable to assume that Kracauer had at least some second-hand knowledge of Dreyer’s own ideas about cinema. [Return]

References

Catalogue numbers for sources in the Dreyer Archive and other collections are given in square brackets.

Alsted, Christian (1979), Ministeriernes Filmudvalg 1941-1946. Dissertation for Magisterkonferens, Institut for Filmvidenskab, University of Copenhagen.

Aziza, Claude (1997), ‘Filmographie: La Renaissance Au Cinéma’. Nouvelle Revue Du XVIe Siècle Vol. 15, no. 2, pp. 359–69. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25598858.

Blixen, Karen (1992), ’Breve fra et land i krig‘, in Samlede essays. Copenhagen: Gyldendal.

Carpenter, Sarah (2003), ‘Performing Diplomacies: The 1560s Court Entertainments of Mary Queen of Scots’. The Scottish Historical Review, Volume LXXXII, 2: No. 214, pp. 194–225. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25529718.

Dansk Kulturfilm (1948), [cable to Carl Dreyer], 7.5.48 [Dreyer II, A: Dansk Kulturfilm 421-483].

Davis, Blevins (1955), [letter to Dreyer] 29.8.55 [D II, B: 165].

Dreyer, Carl Th. (1945), letter to Mogens Skot-Hansen, 22.10.45. [Korrespondance og notater vedr. forløbet, ‘The Seventh Age’, Filmsager, Statens Filmcentral, Statens Arkiver (hereafter SA)].

Dreyer, Carl Th. and Erik Dreyer (1947?), Mary, Queen of Scots. Original filmplay. Trans. Birgita Lindvad. [D I, B: Mary Stuart, 40].

Dreyer, Carl Th. (1955a), letter 16.5.55 to James Quinn [DII A, 223-237].

Dreyer, Carl Th. (1955b), letter 26.7.55 to James Quinn [DII A, 223-237].

Dreyer, Carl Th. (1955c), letter 9.9.55 to James Quinn [DII A, 223-237].

Dreyer, Carl Th. (1955d), letter to John Grant Booksellers, George IV Bridge, 30.9.55 [D I, A: Vredens Dag, 145].

Dreyer, Carl Th. (1955e), letter to Mr Chambers, 23.8.55 [D I, A: Vredens Dag, 145].

Dreyer, Carl Th. (1955f), ‘Fantasi og farve’, Politikens kronik, 30.8.55 [D VII, 39].

Dreyer, Carl Th. (1956), ‘Notes on My Craft’, Monthly Film Bulletin (aka Sight & Sound), Vol. 25, no. 3, pp. 128-9.

Dreyer, Carl Th. (1959 [1943]), ‘Lidt om Filmstil’, in Carl Th. Dreyer, OM FILMEN. Artikler og interviews, Copenhagen: Nyt Nordisk Forlag Arnold Busck, pp. 62-69.

Dreyer, Carl Th. (1973), Dreyer in Double Reflection. Translation of Carl Th. Dreyer’s Writings about the Film. Edited and annotated by Donald Skoller. New York: E.P. Dutton.

Drum, Jean and Dale D. Drum (2000), My Only Great Passion: The Life and Films of Carl Th. Dreyer, Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press.

EIFF (1950), Festival Press Digest [Edinburgh Film Guild Archive].

Elliot, D.M. (1955), [schedule for Dreyer’s visit to Edinburgh, August 29-30 1955], 29.8.55 [D II, A: 223-237]

Elton, Arthur (1946), Memorandum: ‘Dreyer’s Script’. 10.1.46 [Korrespondance og notater vedr. forløbet, ‘The Seventh Age’, Filmsager, Statens Filmcentral, SA].

Fraser, Antonia (2009 [1969]), Mary, Queen of Scots, London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

Grant, John D (1958), [correspondence with John Grant Booksellers Ltd re. book orders and payment, 15.01 - 03.02 1958] [DII, A: 1527-1530].

Gtz [Knud Gantzel] (1943), ‘“Vredens Dag” savnede Tempo og Nerve’, Politiken 14.11.1943.

Hansen, Miriam Bratu (1997), ‘Introduction’, in Kracauer, Siegfried (1997 [1960]), Theory of Film: The Redemption of Physical Reality. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, pp. vii-xlv.

Hardy, Forsyth (ca. 1947a): ‘Denmark has Thriving Film Movement ToDay’, Weekly Scotsman [D I, A: Vredens Dag, 145].

Hardy, Forsyth (1947b): ‘Arts Review’, broadcast Wed Jan 29, 1947. Scottish Home Service [D I, A: Vredens Dag, 145].

Hardy, Forsyth (1949), ‘Danish Documentary’, Documentary 49, EIFF, p. 18 (Edinburgh Film Guild Archive].

Jonas (n.d. [ca. 1946]), ‘Ny Stortid oprinder’, Social-Demokraten [DI, A Vredens Dag 147].

Kimergård, Lars Bo (1992), Carl Th. Dreyers kortfilmengagement i perioden 1942-1952, dissertation for the degree of cand. phil., University of Copenhagen.

Kn. P. (1947), ‘Hollywood for første Gang i farlig Krise’. Politiken, 8.2.47 [DI, A Vredens Dag 147].

Koch-Olsen, Ib (1949), letter to Dreyer 24.2.49 quoting correspondence from Roger Manvell [Dreyer II, A: Dansk Kulturfilm 421-483].

Kracauer, Siegfried (1997 [1960]), Theory of Film: The Redemption of Physical Reality. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

Kracauer, Siegfried and Paul Oskar Kristeller (1969), History: The Last Things Before the Last. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lester, Joan (1946), ‘Danes Make Great Film’, Reynolds News, 24.11.46 [DI, A Vredens Dag 145].

Loup, Jeanette de (1955), ‘Manden der er film’, Billedbladet 21.9.55, pp. 30-31. [DI, A Ordet 173].

Malmström, Hans (1956), letter to Dreyer enclosing memorandum to Robert L. Cohn re. Maria Stuart, 18.5.56. [DII, A 379-82].

Nygren, Sven (1955), letter to Dreyer 2.2.55 [DII, A 3015].

Poole, Madge (1955), letter to Dreyer 12.8.55 on behalf of James Quinn [D II, A: 223-237].

Poulsen, Knud (1946), ‘Jeg tror paa de gode Films Chancer’, Nationaltidende 4.12.46 [DI, A Vredens Dag 147].

Quadrone, Ernesto (1951), ‘Dreyers Mudundu bukkede under for malariaen’. Originally published in Cinema, no. 61 (1 August 1951). Danish translation by Thomas Harder at http://www.carlthdreyer.dk/OmDreyer/Metode/Dreyer-i-Afrika.aspx (accessed April 17, 2015).

Quinn, James (1955), letter to Dreyer 14.5.55 [DII A, 223-237].

Sevel, Ove (2006), Nordisk Film: Set indefra. Viborg: Aschehoug.

Smith, Rosalind (2012), ‘Reading Mary Stuart’s Casket Sonnets: Reception, Authorship, and Early Modern Women’s Writing’. Parergon Vol. 29, no. 2, pp. 149–73. doi:10.1353/pgn.2012.0141.

Steedman, Carolyn (2001), ‘Something She Called a Fever: Michelet, Derrida, and Dust’, The American Historical Review, Vol. 106, No. 4, pp. 1159-1180.

Sørensen, Lars-Martin (2014), Dansk Film under nazismen. København: Lindhardt & Ringhof.

Thomson, C. Claire (forthcoming 2015), ‘The Slow Pulse of the Era: Carl Th. Dreyer’s Film Style’, in De Luca, Tiago and Jorge, Nuno (eds): Slow Cinema. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Westermann, Inga (1955) [letter to Dreyer 4.9.55 forwarding letter from Sven Nygren of Fox Stockholm] [D II, A: 3113].

Suggested citation

Thomson, C. Claire (2015): History unmade: Dreyer’s unrealised Mary, Queen of Scots. Kosmorama #260 (www.kosmorama.org).