The second decade of the twentieth century witnessed a proliferation of Hollywood films demonizing the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, popularly known as the ‘Mormon’ church, including the blockbuster The Mountain Meadows Massacre (director unknown, 1912), The Danites (Francis Boggs, 1912), and Riders of the Purple Sage (Frank Lloyd, 1918) based on Zane Grey’s 1912 novel of the same name. While most of these films are set in the Wild West and focus on purported and actual idiosyncrasies of the Mormon population of Utah, the film that started the trend is notably different in setting, narrative perspective, and origin. Instead of the Western U.S., the film Mormonens Offer(August Blom, 1911, A Victim of the Mormons) plays out primarily in Europe (presumably in Copenhagen, but the urban setting is generic enough to represent any medium-sized European city) and deals with the infiltration of society as a whole and a single family in particular by a Mormon missionary.

The differences between A Victim of the Mormons and the Mormon-themed films that followed it may derive from the fact that the film was not made in Hollywood at all, but rather in Valby, Denmark, in the studios of the Nordisk Film Company (hereafter referred to as Nordisk). The film premiered in Copenhagen at the Panoptikon Theater, on October 2, 1911. It was released in London soon after, on October 11, 1911, and in the United States on February 5, 1912. The commercial success of this film in Britain and the U.S. inspired the wave of anti-Mormon films mentioned above. The question remains, however, why a Danish studio made the first anti-Mormon film in the first place and what this particular film can suggest about the priorities and preoccupations of Danish film and society in the early twentieth century.

Just as a barrage of media coverage about Mormonism accompanied American politician and Mormon Mitt Romney’s quest for the presidency of the United States in 2011-12, the surge of public interest in the mysteries of Mormon life and history in the early twentieth century that this wave of films represents has a specific socio-political context. The sudden popular fascination with Mormonism in the United States in this period has generally been attributed to the high-profile hearings held in Washington D.C. in 1904-06 concerning the disputed seating of Utah Senator Reed Smoot as well as a concurrent popular crusade against ‘the Mormon problem’ in dime novels, popular magazines, newspapers, lectures, and plays (Olmstead 2004: 203). Yet while this context may account for the popularity of anti-Mormon films among American audiences, it does not adequately address the reasons why a prominent Danish production company would choose to make a film about a relatively obscure American religious community. To answer that question, we must consider the possibilities of silent film as a medium, the priorities of the early Danish film industry, and the relationship between Danish society and Mormonism. In this article, I demonstrate the ways in which A Victim of the Mormons, as an example of the cinematically innovative and commercially successful ‘white slave trade’ film genre, provides intriguing commentary on both the reception of Mormonism in Denmark and the modernization of Danish society in the early twentieth century.

The White Slave Trade Film Genre

In the first few decades of the twentieth century, the Danish film industry played a leading role in the technological and economic development of silent film into a popular, profitable entertainment venue. Danish silent films became a particularly valuable export to the European (and, to a lesser extent, American) markets with the rise of the erotic melodrama, a feature-length narrative genre that was pioneered in Denmark around 1910. Rather than adapting literary or theatrical works for the screen, as would become common practice later, the earliest Danish erotic melodramas tended to specialize in sensationalist narratives concerned with private intrigues that intersected with dangers to the general public, in particular involving criminality and sexuality. The film camera’s dispassionate, all-seeing eye made visible interpersonal relations and spaces previously considered private and hence invisible to outside observers, while the increased length of the new films, more than double the standard for the era, allowed for increased plot complexity and audience identification with the film’s protagonists.

The film generally credited with being the first Danish erotic melodrama is Den hvide Slavehandel(Alfred Cohn , The White Slave Trade), produced by the Århus-based Fotorama studio in April 1910. At 706 meters long, roughly 40 minutes, it was the longest film ever made in Denmark up to that time. It built on both sensationalist literature and widespread contemporary political activism directed against white slave gangs that abducted young women and sold them into prostitution. The film tells the story of an impoverished Danish girl, Anna, who answers an ad for a British lady’s companion but is handed over to a London brothel instead. She manages to preserve her virginity by fighting off her first client and is rescued from further dangers in the nick of time, after a harrowing car chase, thanks to the assistance of a compassionate chambermaid and the heroic efforts of her fiancé, Georg, and Scotland Yard. The film’s suspenseful premise, fast-paced action sequences, and titillating visualizations of such forbidden spaces as a brothel and the criminal underworld made the film a box office success in cities across Denmark.

Fotorama’s white slave trade film was so successful, in fact, that Nordisk decided to copy it outright, frame for frame, though the final Nordisk version is approximately 100 meters shorter than Fotorama’s original. Nordisk had released a short film on a similar theme, called Den hvide Slavinde(Viggo Larsen, ‘The White Slave Girl’) in 1907, but without achieving the runaway success as Fotorama’s much longer film, which allowed audiences to identify much more with the characters. Nordisk’s version of Den hvide Slavehandel (The White Slave Trade), directed by August Blom, was released in August 1910 and ran head-to-head with the Fotorama original across Denmark, often in the same towns at the same time. In contrast to Fotorama’s almost exclusive focus on the Danish market, however, Nordisk had extensive distribution networks in place across continental Europe and was able to export The White Slave Trade to a wide European audience, which brought in substantial revenue.

The combination of The White Slave Trade’s success and Ole Olsen’s shortsighted decision not to buy the international distribution rights to Asta Nielsen’s phenomenally profitable debut film Afgrunden(Urban Gad, 1910, The Abyss) ensured that Nordisk became keenly attuned to the marketability of the titillating combination of romance, danger, and scandal. While state film censorship was becoming increasingly common across Europe in the early 1910s, white slave trade films made taboo topics admissible by virtue of their ostensible pedagogical aim of enlightening the public about the dangers awaiting young women who ventured out into the wide world. Nordisk’s marketing materials for the film expostulate on the danger lurking behind the name ‘the white slave trade—three words full of unease and horror, which cause the fearful motherly heart to tremble and brings a flush of shame and indignation to a father’s cheeks; three words that impertinently strip away all of the twentieth century’s civilization and progress!’ (Nordisk 1910). Although Nordisk claimed to be primarily concerned with exposing the problem of white slavery, however, the films still trade heavily on the disheveled immodesty of young women in compromising situations. Domestic and international box office receipts for The White Slave Trade proved the profitability of this type of sensationalist film about criminal activity, liberally laced with sexual danger and violence.

The success continues - also with men as victims

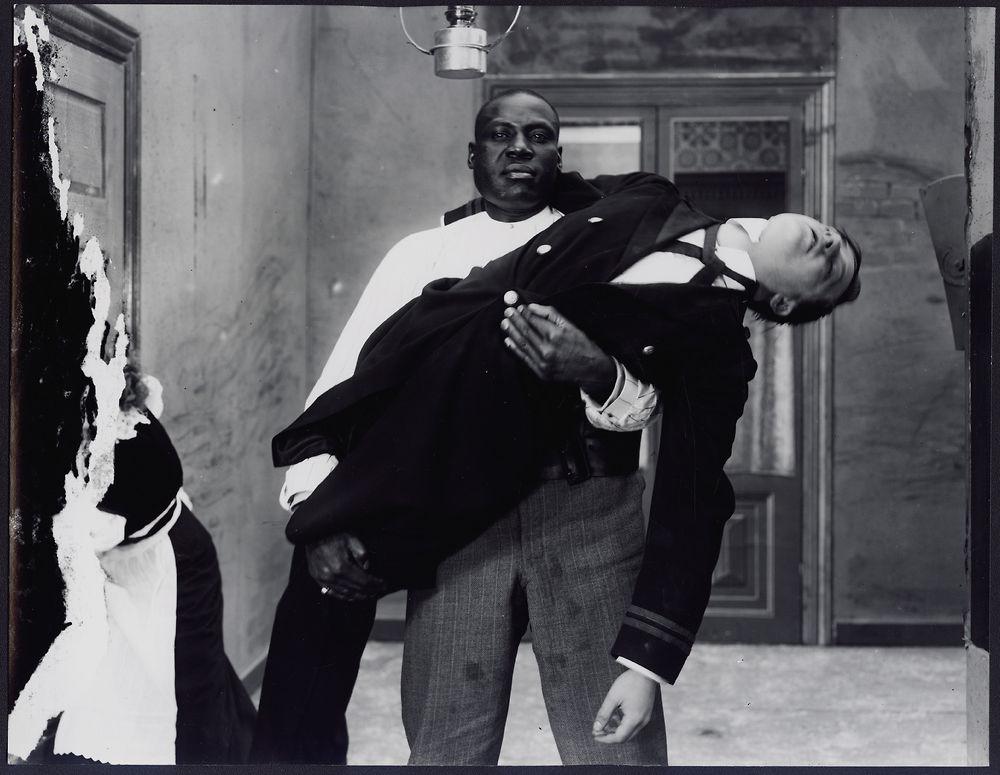

Capitalizing on public interest in the attempted exploitation of young women, both Fotorama and Nordisk released sequels just a few months later. Fotorama’s film, Slavehandlernes Flugt (director unknown, ‘The Slave Traders’ Flight’) premiered on September 15, 1910, while Nordisk’s sequel, Den hvide Slavehandels sidste Offer (August Blom, ‘The White Slave Trade’s Final Victim’) premiered in Denmark on January 23, 1911 and was later released in Britain and the U.S. under the title In the Hands of Imposters. Not much is known about the Fotorama film, but the Nordisk sequel has survived. It filled 930 meters of film and replicated both its predecessor’s commercial success and programmatic nature. The story is slightly more complex than in the first film: Edith, a young woman of good family, is waylaid en route to London, where she was moving to live with an aunt after the death of her mother. Through the machinations of agents of the slave trade who prey on single female travelers, Edith is sold to a lecherous duke, then abducted by a wealthy businessman whose offer to buy her from the duke had been rejected. After resisting the businessman’s advances, Edith is locked away to starve into compliance, but the creole maid guarding her takes pity on her and alerts a young engineer Edith had met on the boat to England. He rescues her from the businessman’s house, only to be beaten up by the duke’s hirelings, who steal Edith back. Thanks to the heroic efforts of the Creole maid and the engineer, with assistance from the British police, Edith is rescued, after a harrowing car chase, and becomes engaged to her savior.

Although the majority of white slave trade films deal in the victimization of women, the film Shanghai’et, eller Mænd som Ofre for Slavdehandel (Eduard Schnedler-Sørensen, 1912, ‘Shanghaied’, or ‘Men as Victims of Slave Trading’) provides a rare exception by depicting a man who falls victim to white slavery as a press-ganged sailor. Like several other films in the genre, Shanghaied was produced by Nordisk, and distributed in Denmark by Fotorama. The film stars Clara Wieth (later Pontoppidan) as Lilly Clausen, the daughter of a ship owner, with her real-life husband Carlo Wieth playing the role of her fiancé Willy, a sailor. True to form, the virtuous protagonist, though male instead of female in this case, is lured into a compromising situation and sold into bondage on board a disreputable ship. Shanghaied distinguishes itself from earlier white slave trade films by its backstory, which involves a rival for Lilly’s affections who orchestrates Willy’s press-ganging. Although Lilly does pursue her fiancé’s trail, the film fails to challenge conventional gender dynamics by allowing her to rescue him. Instead, Willy orchestrates his own escape by leaping from the crow’s nest of his ship in order to be rescued by a nearby naval vessel.

From White Slave Trade to Mormonism

Having exhausted the most plausible scenarios of commercial human trafficking for the time being (aside from a final example of the same type of story, titled Det berygtede Hus (Urban Gad, ‘The House of Ill Repute’), which premiered in November 1912), both Nordisk and Fotorama chose to make films that offered audiences unprecedented access to another social space considered to be both mysterious and dangerous, namely Mormonism. Fotorama’s film, Mormonbyens Blomst (director unknown, 1911, ‘The Flower of the Mormon City’), depicts the travails of a Danish Mormon girl in Utah who narrowly escapes a forced marriage with a Mormon polygamist, but it does not conform to the conventions of the white slave trade genre in several ways. The protagonist Kristine Olsen’s predicament is not the result of her own decision, but comes about a result of her father’s decision to immigrate to the Mormon settlement in Utah and his subsequent failure to conform to the expectations of his new religion, which antagonizes the leaders of the isolated Mormon frontier community. Kristine’s forced marriage has no financial benefit for her abductors, but is intended as punishment for her father’s transgressions. Kristine ultimately escapes her fate with the assistance of her father and a non-Mormon American cowboy, Tom Carter, who eventually brings her back to Denmark, where they purchase her father’s abandoned smithy and establish themselves in rural Danish society.

In contrast, Nordisk’s film, A Victim of the Mormons (1911), subtitled ‘A Drama of Love and Sectarian Fanaticism’ conforms to the paradigm of white slave trade films in nearly all respects. Running an astonishing 1080 meters (3200 feet), A Victim of the Mormons stars the popular Danish actor, Valdemar Psilander, as a Mormon priest named Andrew Larsson (spelled ‘Larson’ in the English-language market release), who persuades a young woman named Nina Gram (Florence Grange, in the English release) to flee with him to Utah. When Nina changes her mind shortly before boarding the ship, Larsson resorts to violence to keep her captive and smuggles her on board. Nina’s desperate brother Olaf (or George) and fiancé, Sven Berg (or Leslie Berg) pursue her all the way to Utah, where they finally succeed in rescuing her, after a harrowing car chase, with the assistance of the police and a compassionate housekeeper. A Victim of the Mormons was only Psilander’s third film, but he was already one of the highest-paid actors in Denmark and had acquired a reputation as a heartthrob and the nickname ‘The whole world’s Valdemar’ (Pontoppidan 1949: 42). His co-star, the hapless Nina, was Clara Wieth, who had previously starred in In the Hands of Imposters and Shanghaied.

The surviving English-language advertising for the film offers one answer to the first part of the question posed at the beginning of this paper, namely why a Danish studio would make the first anti-Mormon film. The short answer is to make money. The commercial success of the previous films in the white slave trade genre had conclusively demonstrated the cinema public’s appetite for scandalous tales of sex, crime, and violence. The savvy businessman Ole Olsen at Nordisk recognized that he could continue his winning streak by adapting folklore about Mormon elders luring young girls to Utah for the screen. Anecdotal evidence from the British and American trade press confirms the acuity of his perception. An ad in Moving Picture World promised the profitability of this latest installment of the White Slave Trade series, proclaiming, in all caps, that it "HAS NO EQUAL AS A MONEY-MAKER" (Chalmers 1912: 315). Similarly, the English trade paper Bioscope declared, "This Great Winner Creates a Record Booking", while broadside ads announced that the picture had been "‘obtained at enormous cost" (Olmstead 2004: 211). A telegram from the Feature Film Co. of America in Rochester, N.Y. to the film’s American distributor, Great Northern Special Feature Film Company, dated March 18, 1912 attests to the film’s financial success, reporting that it "smashes all previous records in receipts’ and calling it ‘without doubt [the] greatest box office attraction in moving pictures ever presented in this city" (Chalmers 1912: 1170).

A Victim of the Mormons: Utah as an illusion

Having established that A Victim of the Mormons fits into the category of the commercially successful Danish ‘white slave trade’ films in terms of narrative, stylistics, and profitability, let us turn to the second part of the initial question, namely the role that Mormonism plays in the film and in early twentieth century Danish society. On one level, A Victim of the Mormons is not terribly concerned with verisimilitude, either in terms of the plausibility of the plot, character development, or setting, let alone providing a historically or theologically accurate depiction of an obscure American religious movement. At the same time, however, the film presupposes a certain basic level of familiarity with the missionary representatives of the LDS church who had become ubiquitous in the U.K., Germany, and Denmark in the second half of the nineteenth century, and does not diverge notably from prevalent popular views of the Mormon religion. This measured approach suggests that demonization of Mormonism per se was not a central aim of the film, leaving open the question of what function this depiction of a Mormon threat to Danish women was intended to serve.

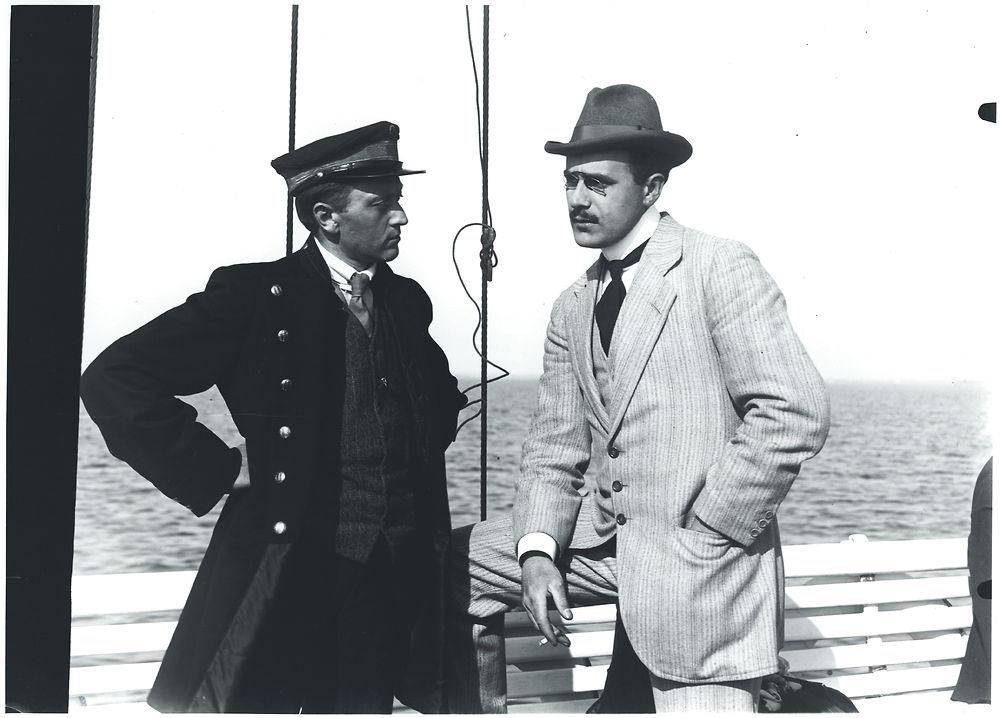

In keeping with Nordisk’s marketing strategy in this period of deliberately rendering Danish films “placeless’ and therefore universal, the urban setting of A Victim of the Mormons is supposed to represent an indeterminate metropolis. It would likely have seemed plausible as such to international viewers, although Copenhagen audiences would likely have had a harder time suspending their disbelief, due to the familiarity of the exterior sets. Marguerite Engberg points out, for example, that the seaside shots are unmistakably filmed along the northeastern coast of Zealand, looking out at the Øresund (Engberg 1977: 365). The dock at which the characters embark for their transatlantic journey is far too small to service ocean-faring steamships and indeed, the journey from Copenhagen to Salt Lake City is accomplished in a few minutes aboard a small ferry in Copenhagen harbor.

Given the specificity of the Mormon theme, however, the director had no choice but to attempt to depict a place purporting to be Utah, but even this filmic image of a specific, real place is rendered in broad, vague strokes. There is no depiction whatsoever of the journey from New York or Boston across thousands of miles of American territory to reach Utah, and the temple in Utah is represented by one of the classical-style buildings in the Zoological Gardens in Copenhagen. Most of the scenes set in Salt Lake City are interior shots, which are suitably generic, but some crucial scenes incorporate external shots. For example, the obligatory car chase in the film crosses a bridge, which ostensibly exists somewhere in Salt Lake City, and ends at the Great Salt Lake. However, the dense cityscape behind the bridge is distinctively European and there is no sign of either the mountains or desert that surround the actual Salt Lake City and Great Salt Lake.

While such discrepancies may be jarring to modern viewers who have either first- or second-hand familiarity with both landscapes, contemporary audiences would not likely have been alarmed by or even aware of them. Mark Sandberg suggests that the decision to employ geographic short-cuts of place substitution in exterior shots set in Utah relied on the presumption that few, if any, of the film’s intended European viewers would have a clear mental image of the scenery of the Utah territory. He explains, “For the original audience, however, the license taken would likely have been perfectly plausible, since the look of Salt Lake City was probably visually unverifiable for most viewers in the European audiences Nordisk was targeting. For most viewers, the idea of “Salt Lake City” was simply not part of their mental geography” (Sandberg 2013). Moreover, since Nordisk consciously oriented itself and its productions in this period more toward a broad European market than a domestic Danish one, the producers may well have calculated that most of those viewers would not recognize the Copenhagen cityscape either.

The film's depiction of Mormonism

The film’s depiction of the Mormon elder, Andrew Larsson, is also fraught with inconsistencies. Andrew is first introduced as Olaf Gram’s schoolmate, an association that lends him social legitimacy and presumed respectability. He is clearly admissible to Danish social circles, despite his unusual religious affiliation, which is explicitly stated in the intertitle, but raises no eyebrows among the group of Danes whom he joins for breakfast in the first scene. It is only the English spelling of his given name and the Swedish-style spelling of his surname that suggest, however obliquely, that he is an outsider in Denmark. His physical attractiveness and good manners are also emphasized, supporting the presumption of acceptability. Throughout the portion of the film set in Denmark, Andrew appears, according to the program notes, as ‘thoughtfulness personified and attends on her [Nina’s] slightest wish in order to fulfill it straightaway.’ Even in the note he leaves for Nina to coordinate their elopement, he addresses her formally with ‘Miss.’ The notes describe Andrew as ‘a young man—a straight-backed and handsome figure, in whose face a pair of fanatical eyes burn.’ This combination of respectability with a hint of the forbidden is central to his fascination for Nina. Viewers are informed that she deliberately seeks out Andrew’s company, in part because her fiancé Sven Berg is too preoccupied with sports to pay proper attention to her, but also because he represents ‘the mystical, the unknown (Fotorama 1911).

It is unclear whether the flaws in the film’s depiction of Andrew’s behavior, particularly with regard to his adherence to the Mormon health code known as the Word of Wisdom, are simply errors or whether they were inserted intentionally, either to show how unfaithful Andrew is to the precepts of his own religion or as a means of camouflaging his identity to avoid discovery. Both smoking and drinking alcohol are forbidden by the Word of Wisdom. Nevertheless, during the purported Atlantic crossing, for example, after Andrew sedates his reluctant bride-to-be, locks her in the cabin, he goes out on deck for a smoke to calm his nerves:

Yet he is also wearing a false mustache that later comes unglued, prompting the ship’s telegraph operator to become suspicious. Later, in Salt Lake City, when she continues to protest her captivity and he is forced to lock her in the basement, he pours himself a whisky in his living room.

Other unlikely details are merely devices for advancing the action. When Olaf and Sven reach Utah, they have no trouble finding Andrew’s home and obtaining unstinting assistance from his housekeeper (or first wife, as she is described in some English-language reviews), despite the fact that she has never seen them before and most likely speaks a different language from the newly-arrived Danes. When they storm into his house and confront him, he naturally protests his innocence, but Nina is able to push a button in her basement prison that triggers a secret trapdoor in the middle of the Oriental rug that adorns his living room floor, causing Andrew to plunge into the basement and revealing Nina’s prison. The Danish men tear the curtains from the windows and attempt to hoist Nina up, but Andrew, despite the injuries he sustained in the fall, manages to foil them by shooting the curtains to shreds. When Olaf and Sven finally discover the secret panel concealing the basement stairway, however, they crash through the door only to find that Andrew has died of an accidentally self-inflicted gunshot wound.

Clip 2: The dramatic scene in the Mormon's house where Andrew Larsson accidentally shoots himself.

Mormonism in Denmark

Despite these somewhat distracting inaccuracies, however, the foregrounding of Mormonism as a central element of the film lends it a level of cultural depth that is entirely missing from the rest of the genre. The first three Mormon missionaries arrived in Denmark in 1850, less than a year after the June Constitution of 1849 established freedom of religion in Denmark. The Mormon elders’ success in converting 23,509 Danes between 1850 and 1905, more than half of whom emigrated within a few years of conversion (Mulder 1957/2000: 104), ensured that the topic of Mormonism was a controversial one among Danes for more than half a century. Danish newspapers regularly published anti-Mormon articles, authored by such eminent figures as the Reverend Dr. Peter Christian Kierkegaard, older brother of the philosopher Søren Kierkegaard, who was Bishop of Aalborg from 1857 to 1875 and Kultusminister [Minister of Culture, Education, and Religion] in 1867-68 (Allen & Paulson 2007: 105). It is significant, however, that the level of public outrage did not correlate to the number of Danes who converted and left for Utah. Public riots against Mormon meetings occurred frequently in the 1850s (Banning 1960: 12), when Mormon immigration had not even begun, but declined in intensity and frequency at same time as the number of convert-emigrants grew to its peak in the 1870s and 80s.

By the time A Victim of the Mormons was made in 1911, Danish conversions and Mormon emigration were at a fairly stable, relatively low level and public displays of opposition to Mormonism had become a distant memory, while the religious itself was regarded as a source of entertainment. The rather humorous tenor of public discourse about Mormonism in this era can be illustrated by the musical-variety show Københavner Revyen (The Copenhagen Revue) in Tivoli Gardens. Just a few months before the release of A Victim of the Mormons, the troupe staged a production entitled Sommerrejsen 1911 (Summer Voyage 1911) that included a song called Mormons, Mormons Composed by Georg Prehn and performed by a group of silent cinema actors (Jutta Lund, Oscar Stribolt, and Carl Alstrup), the song pokes fun at the already obsolete but still notorious Mormon practice of polygamy. The lyrics of the first verse strike a note of caution about the Mormon threat:

"I agree with the priests, the Mormons have to go. They steal all of our girls, especially the pretty ones. Many a Maren, Karen, and Jutta has bitterly regretted being lured to Utah, where she married some old sparrow, becoming number twelve in the same nest. Mormons, Mormons! America’s help’s just a burden to us. We sophisticated playboys, we can surely manage this ourselves!"

The somewhat serious tone of the first verse, which warns young girls against elderly Mormon polygamists and asserts Denmark’s intellectual independence from American trends, gives way in the second verse to a satirical commentary on the Danes’ own moral laxness:

"On Sunday in his parlor, Jensen hosts a festive dance. He’s going to get Hansen’s wife, while Hansen will get his. But instead Jensen must content himself with Mrs. Hansen’s sister, while she openly cavorts with her brother-in-law’s brother, who is married to Hansen’s mother! Mormons, Mormons! Yes, they must be persecuted, we must fight against them. But wife-swapping, wife-swapping! We have the right to do that here too!" (Prehn 1911).

In the second verse, the prosecution and persecution of Mormons has become an afterthought, a habitual attitude rendered unjustified, even rather ridiculous, by the increasingly liberal social mores of Danish society.

Information to the public and propaganda

Nevertheless, the claim of public advocacy that defined and justified the white slave trade films required that A Victim of the Mormons situate itself in opposition to a clear and present moral danger facing Danish society. Accordingly, the program notes exaggerate the threat posed by Mormonism to Danes, both in terms of heretical doctrine and enticement to emigration:

"In the same manner as the great film dramas exposed the evil deeds of which the so-called ‘White Slave Trade’ has made itself guilty and thereby performed a valuable public service by warning young girls against the traps laid for them by the representatives of this shady business, --in the same way this art film ought to be well-suited to opening people’s eyes and directing their attention to the agitation promoted by the spokesmen of Mormonism in order to lure young men and especially women over to Salt Lake City. Anyone who has seen this film and read these notes has been warned against Mormonism’s deception. May this warning bear fruit!"

The audience is then promised the opportunity, by means of "the powerful imagery of the silent theater," of witnessing first-hand the "unhappiness, the infectious disease that erupts in a harmonious family circle by association with a heartless representative of modern Mormonism" (Fotorama 1911).

Yet although the program notes rehash standard boilerplate anti-Mormon propaganda - accusations that Joseph Smith, the founder of the LDS church, was a fortune-teller, that the witnesses to the Golden Plates were a band of felons, and that the Book of Mormon is identical with a lost novel written by an obscure American named Solomon Spalding, to name just a few examples -interspersed with still photographs from the film, the depiction of Mormonism in the film itself is, on the whole, generally objective and accurate, while still underscoring its foreignness. One of the longest scenes in the film depicts Nina’s attendance at a Mormon worship service in Europe. The meeting is held in a nondescript storefront, with signs in the windows and sandwich-boards on the sidewalk out front announcing, in English, ‘MEETINGS’ and ‘WELCOME.’ The camera documents several groups of people entering the building before Nina arrives, dressed in sumptuous black satin and an ostentatious hat that sets her apart from the rest of the attendees, most of whom are quite plainly attired. Upon entering the building, she passes a board outlining the schedule of meetings, again in English: Sunday School, Relief Society, Mutual, and Service. The room is decorated with festive garlands. Andrew is the primary speaker. Nina sits in the front row and looks rather ill at ease during the meeting, but there is nothing inflammatory about the scene.

Clip 3: The Mormon service in a humble store room somewhere in Europe.

The representation of Mormon practices in Utah is handled in a slightly more sensationalized manner, with considerably less theological accuracy, but without apparent malicious intent. Shortly after his return to Utah, Andrew participates in what the intertitle describes as ‘A Mormon Baptism in the Temple,’ though the generic pillared façade bears little resemblance to any existing Mormon temple, let alone the distinctive Salt Lake Temple with its six towers. The scene ostensibly takes place in the temple baptistry, where a large font stands on the backs of three pairs of kneeling golden oxen, with a large pipe organ behind it. Men and women dressed in black are seated in the foreground, while a row of young women in flowing white robes and long, loose dark hair take turns entering the font to be immersed. Contrary to actual Mormon baptismal practice, which involves a clasping of arms, the man in the font pushes down on the women’s heads to immerse them, whereupon they exit the font, line up in a row, and gesture dramatically in unison, pointing across their bodies out of the frame, a completely anachronistic but highly dramatic gesture. Somewhat jarringly, neither the women’s hair or robes, nor the robes of the man in the font, are at all wet after being ostensibly immersed in the font. Aside from the inherently voyeuristic nature of a sequence set inside a space sacred to Mormon believers and inaccessible to non-believers, however, the scene does not succumb to the temptation to depict Mormon ordinances as immoral or obscene as American anti-Mormon films from the later twentieth century often do.

Clip 4: Back in Utah: Andrew participates in a Mormon baptism in The Temple.

Conclusion

In closing, let us return to the question of what A Victim of the Mormons may reveal about the nature and preoccupations of Danish society in the early twentieth century. On a very basic level, the film’s matter-of-fact treatment of Mormonism reveals both that Danes were familiar enough with the religion to associate certain traits and rituals with it and that they retained at least some measure of distrust toward it, even though it no longer drove them into the streets to protest. The introduction of religious freedom in the mid-nineteenth century disrupted Danish society in very tangible ways, while the rapid spread of Mormonism in the succeeding decades aroused considerable fear and consternation among Danes. These negative emotions were in part a response to the somewhat abstract, existential crisis inherent in the fact that thousands of their neighbors were abandoning the church that had, until a few years earlier, defined their national identity. Of even more immediate importance, however, was the fact that the resulting emigration of so many day-laborers and tenant farmers, who were disproportionately receptive to a message of change and chosen-ness, destabilized the social and economic hierarchy that had made possible the rise of the rural middle-class of landowning peasants in the early nineteenth century, namely the cheap labor provided by the same day laborers and tenant farmers who were leaving for Utah.

On a metaphorical level, the film’s exaggerated depiction of Mormonism, in the style of the white slave trade films, as a contemporary threat to the safety of Danish women that could only be defeated by the aggressive intervention of male protectors suggests that the film is engaging with broader cultural discourses about gender roles and modernity in early twentieth century Denmark. At a time when women’s emancipation movements were gaining momentum across Scandinavia and America, the implicit allusions to the Mormon practice of polygamy, which had already been defunct for two decades by the time the film was made, not only trigger righteous Lutheran indignation that any man should think himself entitled to more than one wife but also indicate a lack of confidence in women’s mental and physical abilities to make choices that are best for either themselves as individuals or society as a whole. By way of example, Nina chooses to run away with Andrew to Utah, but her susceptibility to making such a choice is attributed to her irrational emotional reactions to her fiancé’s boorish behavior and her seducer’s aura of mysticism. When she changes her mind, her physical weakness and timidity prevent her from being able to escape successfully, even when Andrew’s housekeeper in Utah helps her flee through her open, unbarred window.

Although a single film is certainly not foundation enough upon which to base a definitive judgment on the state of Danish society in the early twentieth century, there is enough correspondence between the film and the economic, social, and historical conditions that inspired it to justify considering the film’s depiction of Mormonism in Denmark as one thread in a complex web of contemporary Danish sociocultural identity constructions. A final passage from the program notes to A Victim of the Mormons illustrates the way in which the film implicitly conflates the existential threat posed to Danes by Mormonism with the dangers of modernity:

"Is it not a source of shame for civilized humanity, that—in precisely the same century that the cause of enlightenment and liberalism has made such giant strides forward everywhere that the white race builds and dwells—America and then the rest of the world have witnessed the rise and spread of such a cancer as Mormonism, thanks to thousands and thousands of men and women, of whom one would have expected greater acuity and less gullibility, welcoming this false and fraudulent doctrine and praising this new “gospel” as an authentic revelation!" (Fotorama 1911).

By highlighting the importance of the fact that the dawning twentieth century seemed to be such a liberal and enlightened age, as evidenced (ironically, to the modern reader’s eyes, but not, presumably, to its intended audience) by the spread of European colonialism and imperialism, the author of the notes intends to prove the anachronistic and therefore suspect nature of Mormonism. Instead, he casts doubt on the rationality and maturity of his fellow Danes, the "thousands and thousands of men and women, of whom one would have expected greater acuity and less gullibility." Such citizens of an enlightened world should apparently have been better able to resist the lure of smooth-talking, good-looking, well-mannered Mormon missionaries than Nina Gram turned out to be, but they were not. By implication, to which other false ideologies might such innocents be susceptible? By 1911, the alleged dangers of Mormonism were old news in Denmark, but their dramatic cinematic defeat in A Victim of the Mormons may have been intended to warn viewers that many kinds of ‘false and fraudulent doctrines,’ including ones that could be particularly dangerous to women, lurked behind the alluring freedoms of the new century and the new customs of modern life, which should therefore be regarded with wariness.

Suggested citation: Allen, Julie K. (2013): The White Slave Trade gets Religion in "A Victim of the Mormons", Kosmorama #249 (http://www.kosmorama.org/ServiceMenu/05-English/Articles/A-Victim-of-the-Mormons.aspx).

Works Cited

Allen, Julie K. and David Paulson (2007). The Reverend Dr. Peter Christian Kierkegaard’s ‘About and Against Mormonism’ (1855). BYU Studies 46:3, pp. 100-156.

Banning, Knud (1960). Forsamlinger og Mormoner. Copenhagen: Gad.

Chalmers, J.P., ed. (1912). The Moving Picture World. Volume XI. January-March. New York: The World Photographic Publishing Co.

Engberg, Marguerite (1977). Dansk stumfilm. 2 vols. Copenhagen: Rhodos.

Fotorama (1911). Program notes for Mormonens Offer. Et Drama om Kærlighed og sekterisk Fanatisme.

Mulder, William (1957/2000). Homeward to Zion. The Mormon Migration from Scandinavia. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Nordisk Filmselskab (1910). Publicity materials for Det hvide slavehandel.

Olmstead, Jacob W. (2004). A Victim of the Mormons and The Danites: Images and Relics from Early Twentieth-Century Anti-Mormon Silent Films. Mormon Historical Studies, Spring 2004: 203-221.

Pontoppidan, Clara Wieth (1949). Eet liv - mange liv. 4 vols. Copenhagen: Westermann.

Prehn, Georg (1911). Sommerrejsen 1911, Københavner-Revy i 2 Akter, af 2x2=5. Copenhagen: Wilhelm Hansen.

Sandberg, Mark B. (2013). Location, "Location": On the Plausibility of Place Substitution. In: Border Crossings. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

JULIE K. ALLEN / UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN, MADISON

Watch the films at Stumfilm.dk: