Future Vice President turned murderer. Frank Underwood is standing in front of his bathroom mirror looking himself in the eye and smiling his almost invisible smile. The road to the pinnacle of power is awash with deep red human blood in the TV series House of Cards (Netflix, 2012-). A few minutes ago, he threw the persistent reporter Zoe Barnes in front of a subway train. In a moment he will be sworn in as the Vice President of the United States of America.

His gaze is maintained a little too long, and that is how we know what is about to happen. A second later, Frank Underwood looks his audience in the face and poses the rhetorical question: “Did you think I'd forgotten about you?” By staring us down, he breaks through the fourth wall that normally functions as a safe barrier between the made-up space of the narrative and the reality of the viewer. Fiction becomes metafiction when the narrative breaks with the agreed-upon rules of the genre and points to itself as a construction.

Frank Underwood breaking the fourth wall and welcoming us to the second season of House of Cards.

When reading a novel, it is natural to accept and identify with the illusion and be invested in the outcome. Who is the killer? Will the lovers get together in the end? It is also natural to reflect on how the story is communicated. Is the acting believable? Are the CGI effects in a science fiction film hopelessly primitive? And is the chronology of a film particularly odd?

Metafiction occurs when the first level of reflection is challenged by the second. When the communication of a text contributes to the constitution of a work just like when Frank Underwood looks the camera and the audience in the eye. Metafiction can be formed in an infinite amount of ways and is determined by the interplay with the audience. To some, Michael Haneke's Caché (2005) will exclusively be an exciting thriller about a family who receives mysterious surveillance tapes. To others, the film will point to the audience as voyeur because it can also be viewed as a critique of the way in which we find a sadistic enjoyment in following the family's collapse.

Historical metafiction

Self-referential aspects of fiction are as old as film itself. Miguel de Cervantes' opus Don Quixote (1605 and 1615) is often characterised as an early example of a self-referential text from when novels were still in their infancy. H.C. Andersen's fairy tales are filled with frame stories where a third-person narrator before, during, and after the story comments on the plot of the narrative. This is often done in a manner that drives home the moral of the story.

In the era of silent films, a pianist would sit in the theatre playing the piano, often improvising what would be the soundtrack of the film being shown. Though the technique would most likely have been received with wonderment, it highlighted the artificial aspects of the narration when the moving pictures were not accompanied with on-screen audio.

Later on, as the film medium became capable of communicating with on-screen pictures and audio simultaneously, the possibilities of metafiction were split into an array of new variations. Still, metafiction as a concept – and a theoretical understanding of metafiction in a historical context – was not formed until 1970 when the critic and philosophy professor William H. Gass used the term metafiction in his essay, Philosophy and the Form of Fiction (1970), describing the problematic distinction between fiction and reality in a new wave of American literature.

This relation once again becomes topical in the 2000s with the resurgence of autofiction in literature – for example, the controversy in Denmark around Claus Beck-Nielsen's identity project, the Norwegian Karl Ove Knausgård's six-part biography, and Knud Romer’s Den som blinker er bange for døden (He Who Blinks is Afraid of Death, 2006). Furthermore, a number of films and TV series use the relationship between fiction and reality as a theme and as a conscious tool in their storytelling. With Irréversible (Gasper Noé, 2002), French cinema's enfant terrible presented a story told in reverse using gyroscopic camera movement, grainy frames, and a nauseating tone deliberately made to channel to the audience the powerlessness and disgust of the characters. The mission was successful: firemen had to assist 20 people with oxygen masks when the film premiered at the Cannes Film Festival [1]. The comedy series Modern Family (ABC, 2009-) makes use of interview settings mimicking the confessional being used in reality television to create an air of authenticity between the audience and the characters; Frank Underwood speaks to the viewer directly in House of Cards; and back home in Denmark, the comedy series, Klovn (Klown, TV2 Zulu, 2005-2009) points to itself as a construction by blending real life data with made-up and bizarre scenarios. Thus, the comedy genre embodies a viewing culture where the negotiation between the work and audience's understanding of media and culture is a requirement [2]. Also, LOST (ABC, 2004-2010), Curb Your Enthusiasm (HBO, 2000-2011), The Office (BBC, 2005-2013), and Sex and the City (HBO, 1998-2004) make use of various self-commenting devices.

But what is metafiction, and how do you slim down the seemingly infinite scope of the concept?

In her principal work about metafiction professor of literature Patricia Waugh defines it as:

A term given to fictional writing which self-consciously and systematically draws attention to its status as an artefact in order to pose questions about the relationship between fiction and reality (…) A theory of fiction through the practice of writing fiction (Waugh 1984: 2, 39).

Another professor of literature, Marc Currie, has the following definition of metafiction: “… a kind of writing which places itself on the border between fiction and criticism, and which takes that border as its subject” (Currie 1995: 2). They both draw the outlines of a concept which can be used thematically as a way of critiquing art-forms, or more precisely: a form of narration that assimilates every form of critique in the narrative itself.

It is interesting that Currie does not put metafiction in the genre of fiction but rather sees it as a hybrid medium, existing somewhere on the threshold between fiction and critique, between illusion and reflection. Currie brands metafiction as a concept where fiction and critique – two tendencies that seem to be mutually exclusive – are able to coexist fully within the confines of the same work. Professor of cinema Robert Stam is one of the only theorists who does not only talk about metafiction as a literary phenomenon. He takes metafictional films by Hitchcock, Allen, and French nouvelle vague directors in his skilled hands in his principal work, Reflexivity in Film and Literature. From Don Quixote to Jean-Luc Godard (1985).

Since then, a long list of theoretical contributions have been added, for example Bolter and Gruisin’s hypermediacy-concept in Remediation: Understanding New Media (2000)[3], the anthology Puzzle Films. Complex Storytelling in Contemporary Cinema (2009), and Jason Mittell’s Complex TV: The Poetics of Contemporary Television Storytelling (2012).

In the anthology Metafiktion – selvrefleksionens retorik (literally: Metafiction – the Rhetorics of Self-Reflection, 2001), the Danish professor of language and literature Anker Gemzøe presents an excellent typology of variations in metafiction, a typology that operates one level above genres, periods, and art directions. The typology is for use on the written genres.

By expanding Gemzøe’s typology to be adequate when analysing audio-visual genres as well, the aim of this article is therefore to demonstrate how and why metafictional variations are also used in a broad variety of films and TV series. In addition, I will present a definition of the concept and emphasise the wide span of metafiction by providing examples from three distinct works: the drama series House of Cards, the feature film Funny Games U.S. (Michael Haneke, 2007), and the documentary Waltz with Bashir (Vals im Bashir, Ari Folman, 2008).

In addition, I also argue that metafiction, despite the name, is not limited to the various genres of fiction. Just as fiction can be viewed as a rhetorical strategy or way of telling stories, metafiction should be seen as a cross-media resource able to exist in and influence different genres across media without metafiction being defined as a genre itself. As a way of containing the complexity of metafiction as a concept, I propose to characterise it as a narrative modus operandi.

Definition

As a way of summarising the concept of metafiction in all its diversity, modality, and audience attention, I propose the following definition:

Metafiction is a narrative modus operandi that thematises the construction of a work and the relation between fiction and critique through the concurrent presence of illusory and reflexive elements. Metafiction often necessitates an observant and active audience perspective.

With this definition, my aim is to draw the contours of a narrative modus operandi that can be formed in various ways but containing the interplay of narrative and communication as the driving force. The term critique is used in the definition in a broad sense, including examples of metafiction where the entire work, either explicitly or allegorically, is a critique of violence in film for example, or of the medium of film itself, in which case metafiction gets closer to poetics or a manifesto as in the previous example of Caché. The broadness also includes examples where the term can be understood as more ludic or playful with metafictional devices teasing or titillating the audience. When Uma Thurman's character in Pulp Fiction (Quentin Tarantino, 1994) says “Don't be so square” while at the same time drawing a square with her hands, it makes us notice the contrast between illusion and communication, without the mentioned act reflecting a larger artistic agenda.

Uma Thurman cleverly makes us notice the director and the possibilities of the film medium in Pulp Fiction.

Typology

In the following, I present seven variations of metafiction. Sections 1-4 are derived from Gemzøe’s theoretical terms, whereas sections 5-7 are my theoretical additions.

- Author meta

- Addressee meta

- Composition meta

- Inter meta

- Cinematic language meta

- Genre meta

- Para meta

1. Author meta

Author meta constitutes forms of metafiction where the director draws attention to himself and his ability to manage a narrative. In films and TV series, author meta is primarily seen through the voice-over technique which can represent the director's voice or a person in the diegetic universe elevated from the space of the narrative by acting as an omniscient commenter of the narrative. This is evident in Citizen Kane (Orson Welles, 1941) and with Edward Norton's schizophrenic narrative voice in Fight Club (David Fincher, 1999). In Life of Pi (Ang Lee, US, 2012), the voice of the frame narrator and the first-person narrator melt together. A rare circumstance, as in Sunset Boulevard (Billy Wilder, 1950), sees first-person narrators who continue commenting even after dying in the fictional universe. In other cases, the ontological lines are crossed by having the creator meeting his creations, as seen in Adaptation (Spike Jonze, 2003), where the creator also philosophically ponders about the transformational process from novel to film.

2. Addressee meta

Addressee meta constitutes works in which an entity from the diegetic universe addresses the reader or viewer directly, often, in the case of audiovisual genres, by breaking the fourth wall and looking straight into the camera and the eyes of the audience. The purpose of the addressees are quite different; in Funny Games, the fourth wall is broken to give the audience a guilty conscience about enjoying senseless violence in the media. Here, the communication takes the form of moral judgement and critique. In House of Cards, the lead character confides in the audience to reveal the hidden agenda in his political scheme. The act creates a relationship of confidence between character and audience. In the TV series The Office, the direct communication is used to mimic the talking heads of the documentary genre. In comedies, direct communication can take a humorous educational tone as in the spoof film Ghettoblaster (Paris Barclay, 1996), where the lazy loafing main characters with an ironic air encourages the audience to stay in school.

The Verfremdung theatre of Bertolt Brecht was meant to challenge the emotional engagement of the audience:

You have not demanded enough of the theatre, if you only demand recognition, instructive depicts of reality. Our theatre must awaken the joy of recognition, sparkle the pleasure of changing reality. Our audience shall not just hear how you liberate the chained Prometheus but also obtain the desire of releasing him (Brecht 1957: 107).

Also, many Shakespearean characters confront the audience in a number of inquiries or comic confessions. When inquiries shift our attention from the narrative to the dissemination, we might label the incident as addressee meta.

The protagonist in Amélie (Jean-Pierre Jeunet, 2001) often breaks the fourth wall to tell the audience about her inclinations and guilty pleasures.

3. Composition meta

Composition meta constitutes a self-referential emphasis on all variations of composition that defines a work. One key example is the deviation between the narrative chronology (story) and the exposition (plot), which in principle can be achieved in an infinite amount of ways. David Bordwell points out that art films in particular work with an often-enigmatic narratology inviting reflection on the part of the audience:

The art cinema foregrounds the narrational act by posing enigmas. In the classic detective tale, however, the puzzle is one of story: Who did it? How? Why? In the art cinema, the puzzle is one of plot: Who is telling this story? How is this story being told? Why is this story being told in this way? (Bordwell 2007: 155).

In Pulp Fiction, a fragmented chronology makes it possible for John Travolta's character to be killed off midway through the film only to appear at a later stage very much alive. In Inception (Christopher Nolan, 2010), the shattering, causal events unfold like a Chinese box where different plot details are unveiled at different times and at different speeds within the same narrative. Warren Buckland and Bordwell both point out that puzzle films are becoming more and more mainstream and mention film titles like The Game (David Fincher, 1997), The Sixth Sense (M. Night Shyamalan, 1999), and The Others (Alejandro Amenábar, 2001) (Bordwell 2006, Buckland 2009). As Jason Mittell demonstrates in Complex TV: The Poetics of Contemporary Television Storytelling (2012), the concept of complex storytelling has spread to the territory of the TV series, especially in the wake of the new golden era of the genre and hence the growing demand of reinventing and redefining the storytelling systems. The TV series Lost (ABC, 2004-2010) elegantly makes use of flashbacks, flashforwards, and flashsideways as a way of examining the narrative possibilities of time travel. Works like these are characterised by a staggering multi-dimensionality that challenges our preconceived ideas of time, space, and causality. When all these compositional variations specifically draw our attention to the construction, they are representations of composition meta.

4. Inter meta

Inter meta constitutes intertextual communication that can be formed through references to directors, works, fictional persons, genres, etc. References can also move across different media platforms. The reference can be discrete, or it can be part of the entire premise of the work. As Haastrup tells us in her thesis about intertextuality, not all intertextual references are metafictive and vice versa. The defining factor is whether the distinctive character of the references is accentuated in the universe depicted. At the same time, intertextuality is a game with an alert and informed audience which catches on to the reference from a position of broad media cultural knowledge. In other words, many references will be illustrations of metafiction, but they will still be unnoticed by parts of the audience. “The knowledge of the pre-existing texts is a necessary condition in order to appreciate the present text” as Umberto Eco points out. Eco illustrates the point with an exotic example from E.T. in which the alien meets a boy dressed as a gnome from The Empire Strikes Back (Irvin Kershner, 1980). To encode the sophistication of this reference, one must recognise the creature from the Star Wars film and know about the friendship of the directors Lucas and Spielberg and that the special effects artist Carlo Rambaldi created both E.T. and the gnome (Eco 1990a: 123).

The widely known TV cartoons The Simpsons and Family Guy both parody a giant web of media cultural works and events. The references help to remind us that the work has a distinct sender and is part of a larger media and art historical context. A particular variation of references, which Haastrup does not discuss, is product placement. These are products, paid for by sponsors, that naturally enter into the diegesis but may draw attention to themselves by referencing a product, a producer, or a brand. A glaring example is the Carlsberg truck in Spider-Man (Sam Raimi, 2002) appearing in certain sequences to steal the focus from the main character.

5. Cinematic language meta

Films and TV series have a large repertoire of artistic effects and devices within the language of film that, both consciously and subconsciously, can evoke responses. The subconscious aspect can be elicited through non-believable acting or props, a visible boom pole in the frame, or poorly done special effects. Much more often, the language of film uses effects and devices to consciously demand our attention. In The Art Cinema as a Mode of Film Practice (1979), Bordwell argues that the art film genre is defined by a stylistic rhetoric, which is in stark contrast to Hollywood films and their illusory and virtuous presentation. This is exhibited through colour filters, as seen in Le Mépris (Jean-Luc Godard, 1963); black and white frames, as seen in the mathematically themed Pi (Darren Aronofsky, 1998); or via Lars von Trier's lingering slow motion frames in the prologue to Antichrist (2009).

Art and avant-garde films are, in general, a playground for creative and radical style experiments and an exorbitant cinematic language, making them stand out because they challenge the predetermined stylistic patterns of mainstream film. Features in the language of meta film come in a multitude of variations and can, beyond before mentioned examples, include out-of-focus framing, the absence of audio, conspicuous use of non diegetic background music, unconventional framing, or sudden shifts in cinematic style as seen in Kill Bill (Quentin Tarantino, 2003) when the live action film changes to a manga cartoon and later to a shadow act. As with inter meta, it is particularly when the otherness of the cinematic language in relation to the narrative is accentuated that cinematic language meta is at play.

6. Genre meta

We use genres to structure the overall division of film and TV variations, and the term represents a line of stylistic and narrative characteristics in a given work. For the audience, though, these genre markers consolidate a line of expectations for the same piece of work (Agger 2009: 85). When a character in a horror film utters: “I'll be right back”, most people will probably have an ingrained understanding of the genre which tells them that the person will not return. Thus, the understanding of genre is implemented in interplay between the work and the receiver of the work. An observant reader or audience is constantly registering a number of cues and will subsequently receive the pay-off if the genre adheres to the conventions of the genre. “The genre affiliation of a work to some degree forms a metatextual aspect in saying something about how the work in question is to be read and understood,” as Gunhild Agger states (Agger 2009: 85, my translation). That is why a work can also draw attention to itself by not supplying relief or catharsis for the predetermined genre conventions which is why it makes sense to talk about genre meta. Quite a new example is seen in Kill List (Ben Wheatley, 2011), where the first third of the film is played out as a classical social realistic drama with arguments flying across the dining table. Suddenly, the film develops to a brutal and graphic hitman thriller, and in the final third of the running time Kill List becomes an outright horror film with metaphysical aspects. A classic example is seen in Raiders of the Lost Ark (Steven Spielberg, 1981) where an Arab of giant proportions draws a scimitar, (a curved sabre), challenging Indiana Jones to a duel. Completely against the genre expectations of the audience, Jones draws a gun and puts an end to the pending fight. The genre parody becomes even more sophisticated in the sequel, where Indiana Jones is once again standing in a life-threatening situation, looking for his gun. This time the director exploits the fact that most people have already seen the previous film, so in yet another genre twist the gun this time is actually nowhere to be found (Eco 1990b: 89). When a film or a TV series draws attention to itself by not meeting the expected genre characteristics of the audience, one can talk about genre meta.

7. Para meta

Para meta is to be understood as an extension of the term para texts which encompasses all of the issues outside of the text that tie in to the work and enhance the degree of contextualisation. Genette divides paratexts into the categories epitexts, which relate directly to the work (the cover of a novel) and peritexts, which do not relate physically to the work and can be published before or afterwards (e.g. advance publicity or a review) (Genette 1987).

Para meta is defined through the question of how events outside of the work, but with a connection to it, can make us re-evaluate the work and its link and place in the real world. The horror film The Blair Witch Project (Daniel Myrick, Eduardo Sánchez, 1999) was initially promoted as an actual tape documenting the paranormal events in an American forest, and several websites containing fake newspaper articles where made to support the collective cross-media hallucination on the part of the audience. Here, an alternative and well thought out marketing strategy helped to contextualise and question the (fictional) relation of the work to reality. In para meta, the context receives an added significance, because the work is adapted to fit the logic of other media, for example circulation value and news criteria (Jacobsen 2014: 51).

The metafictional variations of typology are mutually inclusive. Hybrid variations where more or all variables are present are not unusual, as I will show presently. But first, let us return to the South Carolina congressman Frank Underwood.

The drama series House of Cards from the streaming service Netflix, based partly on Michael Dobbs' novel and the BBC series of the same name, frames the mammoth-sized net of internal power structures on the political stage in Washington. With an admirable eloquence and smarmy charm, Frank Underwood moves up the ranks of Washington politics to the very top through the two seasons currently available. David Fincher directed the first two episodes of the series and from the beginning applied the cool noir style with blue toned colour filters and a symbolic cinematography, which permeates his principal work Se7en (1995) and his most current effort, Gone Girl (2014).

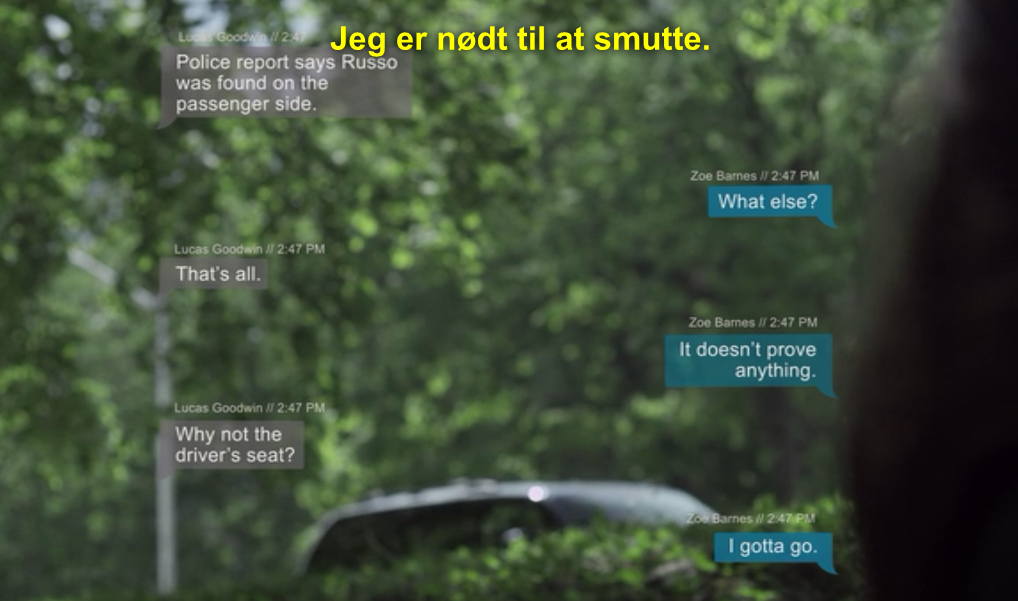

The confessional and the audience as a necessary character

The trademark of the show, and the ultimate reason why House of Cards stands out from other serialised series, is that Frank Underwood addresses the viewer often, and directly. The device is already established in the opening scene of the pilot episode where Underwood puts a dog that has just been run over out of its misery while simultaneously looking into the camera, and delivers a tirade about how the ends justify the means. In relation to the typology, these communications or soliloquies are a great example of addressee meta, sending a nod to Shakespeare, who let Richard III use the same technique.

These communications with the viewer can be long, moralising speeches or consist of a single look sealing the mutual understanding with the audience. In a universe filled with intrigue where Underwood constantly plays with a disguised hand, the relation between himself and the audience functions in a way reminiscent of the confessional in the Catholic Church. Here, the manipulating politician can partly seek penance for his many odious acts and partly clue us in on the next step of his always calculated agenda. For instance, we know that Underwood is only using the up-and-coming Peter Russo for his own personal gain. The metafictive communications include a unique form of suspense because Frank makes the audience the co-conspirators in his misdeeds.

Frank Underwood's confidential interaction with the audience contributes to us sympathising and admiring him in spite of his murderous character. He thereby joins the club of antagonists in heroes’ clothing seen in recent TV series like Breaking Bad (2008-2013, family man with cancer also makes methamphetamine) and Dexter (2006-2013, forensic pathologist executes murderers on the loose).

Do the invocations of Frank Underwood help to enhance the viewer experience, or do they repulse and cause you to remove yourself from the illusion of the political drama series? Even though the answer is dependent on the viewing experience of each viewer in question, I will argue that the communications are a vital part of the foundation of the diegesis. The manipulating lies are an integrated and important part of how the clever politician navigates, even towards his wife, but in the intimate space with the viewer Underwood is honest. Only when he breaks the fourth wall does he speak the truth. He is a cold-blooded killer and an adaptable and consistent liar, but in order to remain focused and calibrate his moral compass he needs a place, and an alliance, where he can explain and defend his misdeeds of the past and his plans for the future.

As an example, in episode seven of the second season Frank reveals to us that he will not tell the president about the billionaire and saboteur Raymond Tusk's contribution to the republicans. There is an insider’s understanding between Frank and the viewer because a disclosure could weaken Frank's position. In the realm of politics where the tiniest leak of sensitive information can be costly, Frank confides in the only people who cannot disclose anything – the audience. My point is that the creators of the show thereby put the viewer on a level with the characters within the confines of the fictional universe. Our coalition with Frank is important to the fictional universe in the sense that Frank does not fall apart from the pressure of all his lies, and is not on the verge of having a confidant abuse the trust given in a world where you can only really trust yourself. Though the communication between the anti-hero and the audience is one sided, the pay-off is not: while Frank receives penance for his sins, the viewer gets to feel like an important person in Frank's inner circle who sits by his side at the altar of power. The metafiction in House of Cards may therefore strengthen the viewer's capability to empathise with the show because the inquiries assign us an important role as an indirect player in the gallery of characters.

In an essay concerning his portrayal of Richard III, the British actor Sir Ian McKellen writes about the inquiries appearing to involve rather than repulse the audience:

All of Shakespeare's troubled heroes reveal their inner selves in their confidential soliloquies. These are not thoughts-out-loud, rather true confessions to the audience. Richard may lie to all the other characters but within his solo speeches he always tells the truth. I never doubted that in the film he would have to break through the fourth wall of the screen and talk directly to the camera, as to a confidant (…) Men and women are all players to Shakespeare [4].

The statement is germane to the metafictional device in House of Cards. The levels of illusion and communication merge into a sophisticated game of narrational forms; with his pep talks, Frank Underwood crosses the threshold between narrative and communication. As a result, the viewer becomes a vital part of the diegetic structure and, thus, the level of the illusion. In House of Cards,the metafictive narrative style is not a device used to make us notice the narrative communication or, in other words, the fictionality of fiction. On the contrary, the creators of the series use metafiction largely as a narrative modus operandi to engage and involve the viewer on the illusionary level.

Social-psychological experiment

Austrian filmmaker Michael Haneke applies metafictive devices in a different and far more provocative way. The director's original version of Funny Games, filmed in German, premiered at the Cannes Film Festival in 1997, but since he did not feel that the critique of the film reached the intended target audience, he made an exact American remake ten years later, named Funny Games U.S. The director's mission with the film was to criticise the audience’s uncritical consumption of violence in the media, and that of the American audience in particular. An example of this is the torture porn genre.

In Funny Games U.S., two young men in white clothes named Peter and Paul are holding a wealthy family captive in their own vacation home. In the span of one night, they involve the family in a long line of sadistic and seemingly aimless games, including extreme humiliation, severe torture, and lastly, murder. Through the first third of the film, Haneke maintains the illusion of a by-the-book thriller of the home invasion genre, but through a sophisticated meta fictive narrative strategy, the film transforms into a social-psychological experiment with the audience at its centre. The film is first and foremost an example of genre meta because the audience is stripped of the catharsis which, for many people, is an ingrained aspect of the experience. In one of the early scenes of the film, the camera zooms in on a knife that by accident slides down to the bottom of the family's sailboat. This is an obvious cue to a genre knowledgeable audience: the knife will eventually become the family's saving grace. But in a meaningless gesture later on, Paul throws the knife overboard, eliminating the mother's hope of survival on the one hand, and denying the audience the genre-specific pay off on the other. A different example occurs when the torture has begun and the father feverishly asks about the motive of the executioners. Paul replies with an easy torrent of words including every standard explanation from mainstream films: his mother was incestuous, his rough childhood environment made him into a drug addict etc.

The pointless violence does not serve dramaturgic but rather a didactic purpose and raises the question: Why do we enjoy violence in film?

Remote control

To further articulate his point, Haneke also applies addressee meta and has Paul confide in the audience repeatedly. "We want to entertain our audience. Show them what we can do" he says with his gaze directly aimed at the audience, and later, "Do you think it’s enough? But you want a real ending with plausible plot developments don’t you?" Morally speaking, the audience gets blood on their hands as it becomes clear that the torture is staged for our benefit [5]. The metafictive devices culminate when the mother manages to grab a gun from the living room table and kill Peter. In a conventional horror film this would have been the dramaturgical turning point, but in Haneke's vision, convention and a causal logic have long been thrown out the window. That is why Paul takes the family's television remote control and rewinds the actual film to the moment just before Ann cleverly grabbed the gun. That way, Paul can knowingly prevent the murder of his friend while it becomes apparent to the audience that the family's doom is inevitable. With the controversial rewind scene, the audience's presuppositions are once again broken because the promised catharsis over the family's revenge is once again taken back. The remote control becomes the director's raised finger didactically reminding the audience that there are no easy answers, and Paul's white gloves become a specific symbol of Haneke's clinical approach. The scene is also a clear-cut example of composition meta as the causal logical construction of the work in time and space erodes.

Through his rhetoric, Haneke tries to puncture the moral habitus of his audience by urging a reflection on the role of non-critical co-catalysts in the production of brutal media violence. Thus, in general the metafiction of the film is a personal condemnation of - and an introduction to a debate on - a media sociological consumer culture, where we bathe in an ocean of of amoral productions of the entertainment industry. As Haneke himself has stated about his uncompromising work: the only morally defensible reaction is to leave the film before it has ended (Wheatley 2009: 99).

Recollection archaeology

Where fiction films and series can incorporate factual markers to thematise the relation to reality, documentary films can follow the same pattern by approaching it the other way around. Self-reflexive documentary films like Stories We Tell (Sarah Polley, 2012) and The Missing Picture (L’image manquante, Rithy Panh, 2013) question the foundation of their own existence by way of an archaeological process of recollection that investigates the relationship between factual reports and memory, and poses the question: how do you document a past that consists only of memory and trauma? This issue is also contextualised through stylistic expression in Ari Folman's animated documentary, Waltz With Bashir, in which the director tries to uncover his role in the Lebanese civil war through interviews as well as deciphering his own war traumas. The point is that specific documentaries can be read as metafiction because they challenge their generic structure with fictional patterns. The use of animation in Waltz With Bashir is an effective artistic choice, which can be used by the director to establish that the representation of the trauma is a caricatured real life story, rubbing up against the validity demands of the genre. The Israeli soldiers in the story remember tableaus and scenarios that never took place as anything other than distorted memories and mental reflections of their consciousness, and maybe because of this, the animation feels like an exact and precise depiction of a phenomenon that cannot be caught by a camera. Because the memory is made up of detached fragments and a causal-logical hierarchy, the animation becomes a loyal form of representation to Folman and the interview subjects' attempt to define their traumatic memories.

In the key scene of the film, which is repeated several times, Folman goes bathing in the ocean at Beirut while the sky is bathed in a phosphorous yellow light. As the shocking finale to the process of realisation being exposed in the film, Folman realises that the yellow bursts of light are actually from flare bombs that he, himself, helped fire over the Palestinian refugee camps in Shatila and Sabra while Christian Phalangists carried out a massacre on the mostly civil population. Thereby, Folman was an accessory to a mass murder that killed upwards of 3500 people. The scenario at the beach is, therefore, a mental cloak Folman has created as an attempt to flee from his guilt and moral depravity. In the last scene, Folman follows the two flare bombs from the beach and into the refugee camps in a slow movement. Through an abrupt shift in style, the animation switches to real life pictures, and suddenly we experience the victims of the massacre through a handheld camera, one that documented the scene a few hours after the tragic event [6]. This moment sees Folman breaking through to the reality that his trauma has previously blocked from his consciousness.

The defining last scene in Waltz With Bashir where animation becomes real life.

Medical record with war trauma

When I want to talk about documentarian metafiction here, it is because Folman shines a light on the relationship between fiction and critique by thematising the very texture of documentaries. The hybrid nature of the work seems indirectly to challenge the categorical, and often narrow, distinction in film making where fiction equals feature films and fact equals documentaries. Folman proves that complex phenomena call for complex (and thereby, precise and inclusive) forms of expression, which means that the work can be read both as a traumatic medical record of war and as a genre-critical proclamation. This is why Waltz With Bashir is an illusory and gripping tale of mental disorder and massive moral complexities while at the same time, on a communication level, an open discussion of, and a challenge to, the barriers of genre and convention.

Through composition meta, the film points to its own construction with a line of questions: What is a documentarian truth? Why is the film animated? Are the memories of the soldiers historically accurate? Where Funny Games is Haneke's critique of violence in film, Waltz With Bashir can be read as Folman's critique of truth in film. The film fits nicely with the definition of metafiction, because Waltz With Bashir thematises the relation between fiction and (genre) critique through the inclusion of illusionary and reflexive elements.

Documentarised works of fiction like Klown and fictionalised documentaries like Waltz With Bashir exist within the same generic frontier land, not easily defined. Often, part of the premise of these works is to reach out a hand towards the audience indirectly, encouraging them to examine the texture of the films and continue the genre discussion.

This article is a humble attempt to take a closer look at the diversity and possibilities of metafiction. By looking at the way a work self-communicates we can also get more insight into the general intention of the work, whether it criticises itself, society or the viewers watching it, and whether the metafictional devices come in the way of an outstretched hand or a provocative middle finger. Think about that the next time Frank Underwood speaks to you.

This article is based on Rune Bruun Madsen's master thesis "Metafiction in Films and TV-series" (2014).

Notes

[1] Brottman 2005: 160. Beyond that, 205 of the 2400 guests and press walked out at the same premiere showing. [Return]

[2] For more on Klown's fictional strategy, see Jacobsen 2013.[Return]

[3] Bolter and Grusin define hypermediacy as: "A style of visual representation whose goal is to remind the viewer of the medium." Though the name of the concept differs, the content is largely the same (Bolter and Grusin: 272).[Return]

[4] McKellen 2007-2014: http://www.mckellen.com/cinema/richard/screenplay/intro2.htm[Return]

[5] The appeal of the film to the audience is also concurrent with the feminist film scholar Laura Mulvey's term voyeuristic gaze which includes a controlled and scopophilic (masculine) gaze finding pleasure in assigning blame, claiming control, and subjecting the blamer to punishment or forgiveness. (Mulvey 1975: 6).[Return]

[6] The news footage was shot by Israeli journalist and television reporter Ron Ben-Yishai.[Return]

Literature

Agger, Gunhild (2009). Genreanalyse (literally: Genre analysis). In: Rose, Gitte and Christiansen, H. C (ed): Analyse af billedmedier – en introduction (literally: Visual media analysis – an introduction). Frederiksberg C., Publisher: Samfundslitteratur.

Bolter, Jay David & Grusin, Richard (2000). Remediation: Understanding New Media. Cambridge. MIT Press.

Bordwell, David (1979). The Art Cinema as a Mode of Film Practice. In: Bordwell, David (2007): Poetics of Cinema. New York, Routledge.

Brecht, Bertolt (1982[1957]): Om tidens teater (literally: The theatre of now). Haslev, Gyldendal. Oversat fra tysk efter Schriften zum Theater. Forlaget Suhrkamp.

Brottman, Mikita (2005). Offensive Films. Nashville, Vanderbilt University Press.

Buckland, Warren ed al. (red.) (2009). Puzzle Films. Complex Storytelling in Contemporary Cinema. West Sussex, Wiley-Blackwell Publishing.

Currie, Mark (1995). Metafiction. London, Longman.

Eco, Umberto (1990a). Om spejle og andre forunderlige fænomener (Original title: Sugli specchi e altri saggi). Copenhagen, Forum Publishers Ltd.

Eco, Umberto (1990b). The Limits of Interpretation. Indiana, Indiana University Press.

Gass, William S. (1970). Fiction and the Figures of Life. Boston, Godine Books.

Gemzøe, Anker (ed) (2001). Metafiktion – selvrefleksionens retorik i moderne litteratur, teater, film og sprog (literallyy: Metafiction – the rhetoric of self-reflection in modern literature, theatre, film and language). Viborg, Publisher: Forlaget Medusa.

Genette, Gérard (1987). Paratekster. In: Jelsbak, Torben & Bjerring-Hansen, Jens (2010): Boghistorie. Moderne litteraturteori 8 (literally: Book history. Modern literary theory). Aarhus University Press, Denmark, side 91-109

Haastrup, Helle Kannik (2010 (2004)). Genkendelsens glæde. Intertekstualitet på film (literally: The joy of recognition. Intertextuality in film) Frederiksberg, Publisher: Forlaget Multivers ApS.

Jacobsen, Louise Brix, et. als. (2013). Fiktionalitet (literally: Fictionality). Frederiksberg C., Publisher: Samfundslitteratur.

McKellen, Ian (2007-2014). ”Richard III. Introduction Part 2”. Blog post. http://www.mckellen.com/cinema/richard/screenplay/intro2.htm

Mittell, Jason (2012). Complex TV: The Poetics of Contemporary Television Storytelling. Online in-progress book manuscript:

http://mcpress.media-commons.org/complextelevision/

Morag, Raya (2013). Waltzing with Bashir – Perpetrator Trauma and Cinema. London, I.B. Tauris & Co.

Mulvey, Laura (1975). ”Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema”. In: Screen #16, fall 1975. Publiceret som online-PDF: http://imlportfolio.usc.edu/ctcs505/mulveyVisualPleasureNarrativeCinema.pdf

Nichols, Bill (2001). Introduction to Documentary. Bloomington & Indianapolis, Indiana University Press.

Raz, Yosef (2011). “War Fantasies: Memory, Trauma and Ethics in Ari Folman’s Waltz with Bashir.” In: Boaz, Hagin (ed): Just Images. Ethics and the Cinematic. Newcastle upon Tyne, Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Roe, Annabelle Honess (2013). Animated Documentary. Hampshire, Palgrave Macmilian.

Russell, Dennis Eugene (2010). The Portrayal of Social Catastrophe in the German-Language Films of Austrian Filmmaker Michael Haneke (1942-). Lampeter, Edwin Mellen Press.

Speck, Oliver C. (2010). Funny Frames – The Filmic Concepts of Michael Haneke. London/New York, Continuum Press.

Stam, Robert (1985). Reflexivity in Film and Literature – From Don Quixote to Jean-Luc Godard. Ann Arbor, UMI Research Press.

Waugh, Patricia (1984). Metafiction – The Theory and Practice of Self-Consciouss Fiction. London, Routledge.

Wheatley, Catherine (2009). Michael Haneke’s Cinema. The Ethic of the Image. New York, Berghahn Books.

Whitehead, Anne (2004). Trauma Fiction. Edinburgh, Edinburgh University Press.

Zimmer, Catherine Adelina (2002). Film on Film: Self-Reflexivity and Moving Image Technology. Berkeley, University of California.

Suggested citation: Bruun Madsen, Rune (2015): When fiction points the finger – metafiction in films and TV series. Kosmorama #259 (www.kosmorama.org)

RUNE BRUUN MADSEN / JOURNALIST AND FILM CRITIC