For a number of years – from the Cannes premiere of Thomas Vinterberg’s Festen (also known as The Celebration) and Lars von Trier’s Idioterne (The Idiots) in 1998 and four to five years beyond that – Dogme 951 was the new trend that the film world talked about. A call for a minimalist, fundamentalist approach to filmmaking, a return to the simplicity that got lost with the triumphs of film technique.

Dogme (the Danish word for dogma) has been dismissed as a publicity stunt, but also evaluated as “one of the most important events in the European film history of the 20th century”.2 At any rate, Dogme – for one brief, shining moment – was the new buzzword that heralded an alternative approach to filmmaking and made contemporary Danish cinema unexpectedly famous.

The old film is dead

Dogme was an idea that Lars von Trier, who invented his ‘von’ to be sarcastic, had been developing for some time. According to producer Peter Aalbæk Jensen, Trier talked about the

Dogme concept back in 1992, when they started the film company Zentropa together.3 Trier had early plans for a book on filmmaking with the title Dogme; he liked this word with its element of a truth that could not be questioned, and the word “felt good in the mouth.”4

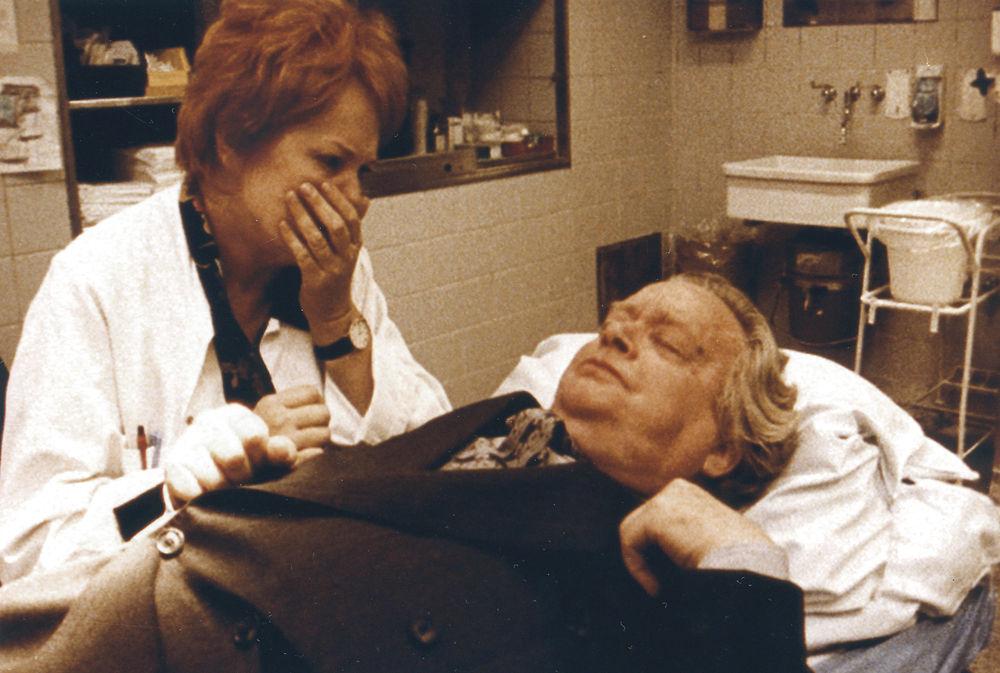

More directly, Dogme was developed from his experience in 1994 with the TV mini-series Riget (The Kingdom) , a mixture of comedy, hospital drama and ghost story, where Trier experimented with using deliberately faulty and imperfect visuals, marked by shaky handheld shots and grainy distorted colors, partly in order to create a special visual style, partly – by omitting a lot of time-consuming lighting preparations for each shot and by ignoring classical rules of film ‘grammar’ like the 180° rule – to simplify (and thereby shorten and reduce the cost of) the shooting process.5

The author of this article (who was Trier’s teacher during his years of film studies at The University of Copenhagen 1976-79) had a telephone call from Trier in early 1995. He wanted to know when was the last time that a film manifesto of some kind had been issued. Trier himself had accompanied his early films, his so-called Europe Trilogy (The Element of Crime (1984), Epidemic (1987), and Europa (1991)) with manifestos.6 But more general manifestos are quite rare in film history.

Dziga Vertov of course wrote several in the 1920s – this was after all a suitable means of expression in the revolutionary USSR – but they concerned documentary films. Also Lindsay Anderson’s Free Cinema manifesto (1956) was directed at documentaries, but it influenced British feature films in the early 1960s as well. There are texts by Cesare Zavattini that present the major thoughts behind Italian Neo-Realism, and two texts, Alexandre Astruc’s Le caméra-stylo (1948) and François Truffaut’s A Certain Tendency in French Film (1954), have a status as forerunners of the ideas behind the French New Wave. In the 1960s, a number of statements accompanied the revolutionary Cinema Novo in Latin American countries.

The most obvious example of a film manifesto, probably, would be the Oberhausen Manifesto of 1962. The short text, signed by 26 young German filmmakers, concluded with the proclamation: “The old film is dead. We believe in the new film.” But it talks only vaguely about “new freedom from the usual conventions of film-making” and “new cinematic language,”7 without specifying what this means.8

Rescue action

1995 was the great anniversary year of cinema, at least from a European perspective. Trier had been invited to participate in the conference about the future of film, Le cinéma vers son deuxième siècle at the Odeon Théatre de l’Europe in Paris in the spring of 1995, exactly 100 years after the Lumière brothers had shown their films for an invited audience (on March 22, 1895), and he found that this was a suitable time for a new manifesto announcing a new approach to filmmaking.

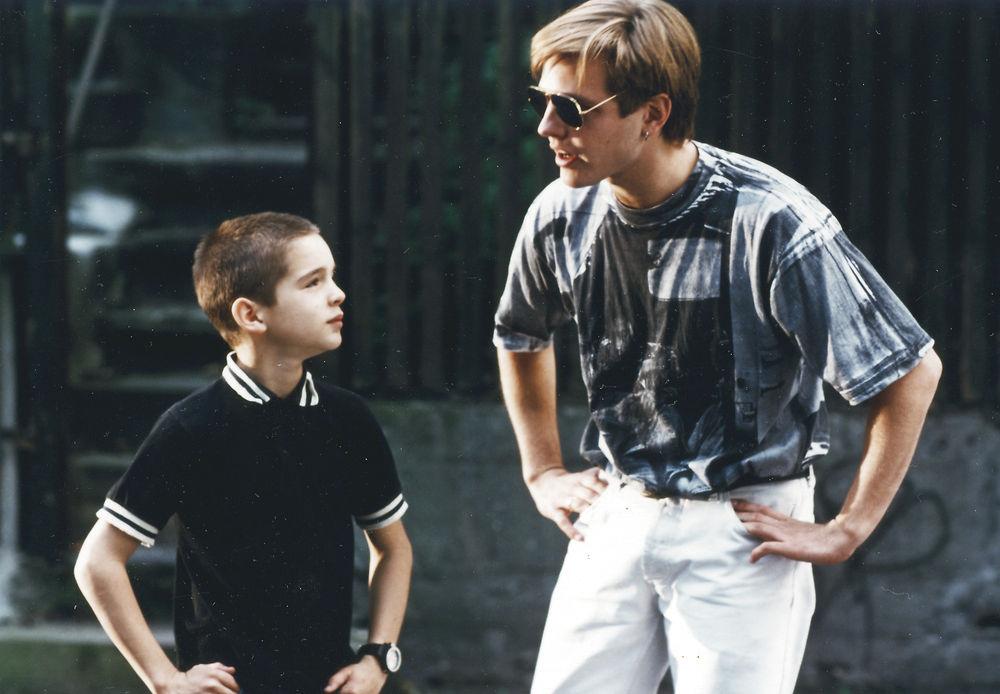

He contacted his colleague Thomas Vinterberg, who had not yet made a feature film (he would do that the following year with De største helte (The Greatest Heroes)), but on the basis of two outstanding short fiction films, Sidste omgang (Last Round, 1993), his graduation work from the Danish Film School, and Drengen der gik baglæns (The Boy Who Walked Backwards, 1994), he was considered the most promising among the young Danish filmmakers. Trier invited him to be co-writer of the manifesto (the Vow of Chastity section) and member of a Dogme 95 group of filmmakers who could carry the new ideas into reality.

The Dogme 95 manifesto, if we sum up the important points of its method and philosophy, is directed at “certain tendencies” in contemporary film, offering a “rescue action” that is basically opposed to “the auteur concept” and “bourgeois” cinema: “We must put our films into uniform, because the individual film will be decadent by definition!” In order to counter that, and in regard to a situation where “a technological storm is raging, the result of which will be the ultimate democratization of the cinema”, a set of rules, the so-called “Vow of Chastity”, is prescribed: 1) the shooting must be done on location and no props brought in; 2) the sound and images must be produced together; 3) the camera must be handheld; 4) the film must be in color; 5) optical work and filters are forbidden, as well as 6) superficial action; 7) the film must take place here and now; 8) genre films are not allowed; 9) the format must be Academy 35 mm, and 10) the director must not be credited. At the end it is announced that the Dogme director must “refrain from personal taste” and “from creating a “work””, and must give up being “an artist”. Instead the “supreme goal is to force the truth out of my characters and settings” and to avoid “any good taste and any aesthetics.”9

The first part of the text has the typical manifesto character – an ideological proclamation where criticism, judgments, and opinions are presented with rhetorical power. The Dogme manifesto clearly has points in common with the earlier manifestos, that in different ways have called for change, freedom and more realism. Most manifestos would stop here. But the originality of the Dogma manifesto is that it not only comes up with the usual declarations and intentions, but that it explicitly offers a particular method of filmmaking, outlines a positive program, an alternative procedure of filmmaking, not in abstract terms but very literal. The ten rules of the Vow of Chastity, mostly prohibitions, represent a therapy, a treatment, and a cure. It equals a harsh diet: painful, perhaps, but good for you in the long run. But it is also a kind of (self)punishment, a confession of faith and a promise of obeying rules that cannot be questioned (the same way religious dogmas cannot). It would later turn out, however, that several Dogme directors had sinned against their vow.10

Back to basics

Central to Dogme is a protest against the establishment, typical for avant-garde movements. The rebellion is not directed against Danish cinema, but mainly against Hollywood:11 Dogme is (European) minimalism versus (American) grandiose mainstream with its “superficial action”, “cosmetics” and “illusion.” But it was also, according to Vinterberg, meant as “a reaction to the laziness and mediocrity in both European and American cinema.”12

Dogme represents a return to simplicity, to a more fundamental and truthful approach to filmmaking. Trier talks of Dogme as “the equivalent of making fire with two stones instead of a Ronson lighter”13 and he compares it to “the early days of film” where “you again experience the wonder of filmmaking as totally new.”14 The idea is to make film “here and now”, using the spontaneity of the moment rather than doing a lot of postproduction ‘repair’ of the scenes. The simplicity is achieved through the use of handheld camera, the ban on artificial lighting and the proscription against later corrections of picture and sound.

Dogme is a search for truth, a rather abstract ambition. It should be noticed, however, that it concerns truth inside a fictional universe. Dogme wasn’t meant for documentary, only for fictional films. Later, in 2001, Trier would present a manifesto with rules made especially for documentaries, the so-called Dogumentary, but it never had a wider impact and never materialized in the form of important films.15

Dogme is also against the auteur status of the director, destroying the romantic myth of the unique artistic personality; for an eccentric artist like Trier, this is a rather masochist rule. It is also part of the anti-aesthetic tendency of the movement, ignoring “any good taste and any aesthetics.”

The Dogme project is not without its paradoxes: Why demand technical primitiveness from a medium so much based on technology? Why fight illusion and look for truth in fiction films, one could ask, when fiction by definition is illusion and invention – why not then make documentaries? How is it possible to avoid “aesthetics” when you work in an aesthetic medium? And if you want the performance of the moment rather than the manipulated version, wouldn’t it be more logical to turn to the theatre with its here and now?

There are no simple answers to this, except that Dogme isn’t an academic approach, but an artistic one, in a field where there are no holds barred.

Low-budget and digital

It should be noted that Dogme is often discussed in connection with two elements that are not mentioned in the manifesto: Dogme as low-budget and Dogme as digital filmmaking.

The Dogme rules do not prescribe anything about budgets,16 and from the beginning Trier very clearly stressed that Dogme is “an artistic concept, NOT an economic one.”17 But nonetheless the Dogme films have typically been inexpensive films as the rules would generally have the effect of diminishing the production costs and appeal to the low budget film culture.

The Dogme manifesto demands – in accordance with its fundamentalist spirit – that the film must be shot on 35 mm film in Academy Format. Where manifestos typically announce a new direction, Dogme, paradoxically, calls for a return to old technology and methods. But the new digital technique had its breakthrough in these years, and Trier realized that video would suit Dogme better18. The group then agreed that “this rule should apply only to the distribution format.”19 Both Festen and The Idiots were shot on video, while Kragh-Jacobsen’s Mifunes sidste sang (Mifune, 1999) was shot on film. And Trier would continue with digital filmmaking.

The video cameras gave new freedom but a less perfect image (corresponding well with Dogme’s disregard of aesthetic matters). The digital technique was behind “the ultimate democratization of the cinema” that resulted in millions of YouTube videos in the next decade. But paradoxically, in its pioneering use of digital video cameras, Dogme was part of the same digital revolution that has brought professional mainstream film to new heights of the illusion and manipulation that Dogme protests against.

Presentation in Paris

The manifesto was written very fast, “on the basis of some notes I had made,”20 Trier has said. Vinterberg has told me: “We sat there and composed those rules in half an hour. It was enormously fast. For me the incentive was the anarchistic, the collective and the totally insane side of it all.”21 It is a common error that the whole original group was behind the text.22

Vinterberg also remembers that the rule about music was his suggestion, and that the rule against crediting the director was Trier’s. A mutual point of interest was the use of handheld camera. Vinterberg has explained:

"For me it came from the Film School, my midterm film, Brudevalsen [The Wedding Waltz, 1991]. I was deeply absorbed by doing something handheld in fiction, and nobody did it at that time. And Lars saw that film before he saw anything else I had made. It was on this background that he asked if we should make a handheld wave. We met at the staircase in Ryesgade [the first address of Zentropa]. He wanted to do the same, he had seen Homicide [American TV series 1993-99]. He had not yet made The Kingdom [Riget, 1994]."23

Trier, for whom control – and letting go of control – has always been a central issue, would later point out his more personally idiosyncratic motive behind the rules:

Truffaut in his time wrote the article about A Certain Tendency in French Film. In fact you could say that Dogme was about certain tendencies in Lars von Trier’s films. And they were some special tendencies that I thought I had become too clever at and which took up too much space. The only way I could make myself make an un-manipulated film was by saying that it was part of the rules. It is about indulgence, about atoning one’s sins.24

Dogme, of course, was meant as a movement, a collective initiative and the idea was to establish a group, to get a handful of filmmakers from different sections of the Danish film world. Besides Trier and Vinterberg, the group included Søren Kragh-Jacobsen, Kristian Levring, and Anne Wivel who soon withdrew from the project (eventually four of the ten Danish dogma films would be directed by women). Kragh-Jacobsen was a representative of the more experienced directors,25 Levring came from commercials; Wivel was a documentary filmmaker.

The Dogme concept was published and discussed in the Danish press. The Copenhagen newspaper Politiken, leading in cultural affairs (and whose chief editor, Tøger Seidenfaden, was Trier’s childhood friend), brought five articles26 where a number of film people commented on Dogme. Producer Peter Aalbæk Jensen, Mogens Rukov, Trier’s former teacher at the Danish Film School who would be an important counsel and co-writer on several Dogme films, Søren Kragh-Jacobsen, and Anne Wivel were, not surprisingly, positive of the initiative, while Film Museum leader Ib Monty, Film School head Poul Nesgaard, film critic and filmmaker Christian Braad Thomsen and filmmaker Ole Bornedal, who had had certain clashes with Trier, were critical and sarcastic. In Information, the leading intellectual newspaper, veteran critic Morten Piil, was also sceptic.27

The international presentation of the Dogme manifesto took place a few days later at the Paris conference among distinguished participants such as Jean-Jacques Beineix, Youssef Chahine, Costa-Gavras, Claire Denis, Abbas Kiarostami, Claude Lanzmann, Manoel de Oliveira, Alain Tanner, the Taviani brothers, and Krzysztof Zanussi. It was March 20, 1995,28 and Trier addressed the audience, as seen in Jesper Jargil’s documentary De lutrede (The Purified, 2002), one of the key works on the Dogme movement: “It seems to me,” he said, “that for the last twenty years – no, let’s say ten, then – film has been rubbish. So – my question was: What can we do about this … and I made some little papers with words on them: It’s called: Dogma 95!”

He then read aloud the manifesto, after which he threw red flyers with the text out to the audience. With his usual ironic attitude, seemingly mocking the political left wing culture of the 1970s, he declined to answer questions about Dogme 95, because, as he said, he had not been authorized to do so by the Dogme group!

Anticipating Dogme

After the Dogme manifesto, but before or parallel to the real Dogme films, a few Danish films arrived that seemed to anticipate some of the Dogme spirit. Jonas Elmer’s Let’s Get Lost (1996), a comedy about a group of young idlers, and Nicolas Refn’s gangster film Pusher (1996), both successful first features by young directors, had created a Dogme ‘look’ by using constraints and limitations as well as handheld camera style on a low budget background,29 as did Linda Wendel’s Mimi og madammerne (Mimi and the Movers, 1998), about a group of friends in a summer cabin. A new more handheld camera style is also visible in the TV series Taxa (1997-99), where Anders Refn, editor on Trier’s Breaking the Waves (1996), and Morten Arnfred, Trier’s co-director on The Kingdom and assistant director on Breaking the Waves, were leading directors. These initiatives can be seen as symptoms that time was ready for Dogme.

Funding problems

The next step was now to carry out the plan of making five Dogme films, by the four Dogme brothers – Trier, Vinterberg, Kragh-Jacobsen, and Levring.

Early in the process of Dogme, the then Danish Minister of Culture, Jytte Hilden, had been enthusiastic about the project. She had been present at the five-hour midnight marathon for an invited audience in November 1994 of The Kingdom, which in one stroke had revealed Trier’s potentials beyond the limits of intellectual art film. According to Trier,30 Hilden, at Morten Arnfred’s birthday reception in August 1995, had promised to grant the necessary fifteen million Danish kroner to the Dogme films. But then the problems started.

Later Trier would complain to the minister: “I had your consent and your good will … what has happened?”31 What had happened was probably that Hilden had realized that she could come in conflict with the so-called arm’s length principle: a Minister cannot personally support a specific project. Rather, it has to pass through the official channels, in this case Danish Film Institute whose commissioners would have to approve any financial support based on evaluation of each script.

Since the Ministry couldn’t make a special grant for the Dogme project, they made instead a pilot scheme where special funds could finance a few low-budget films over the few next years, to be administrated by the Danish Film Institute. The Dogme directors could then apply here. The Dogme brothers, however, found this incompatible with the group spirit of Dogme. In an angry letter, Trier made clear that Dogme was “a collective project, consisting of five films”: "Nothing less can make it into the manifestation that is needed to move anything in the stagnated film world (…) Dogme 95 shall give a long needed push to Danish and international film".32

The Dogme group consequently did not apply for the special funds and complained to the Danish Film Institute that the special funds for low-budget films actually were “the money that the Ministry of Culture had meant for the Dogme 95 project.”33

In December 1996 Hilden had left her position as Minister of Culture, and the Dogme project seemed to have gone to ground. But then the national Danish TV station, DR, became involved in the project, quite exceptionally as DR had never before participated in feature film production without the Danish Film Institute.

DR’s new managing director, Bjørn Erichsen, had started in 1996 and came from a position as leader and originator of the new European Film College (in Ebeltoft, Denmark), where he had acquired close contacts to the film industry which had supported the school. Sven Abrahamsen, DR producer on The Kingdom, suggested to Erichsen that DR should be involved in the financing of the Dogme films now that the Film Institute had let the project go. A special reason for Erichsen’s interest was that DR in August 1996 had started an extra and more intellectual channel, DR2, where exclusive film art like the Dogme films promised to fit perfectly.34 The agreement was made in April 1997 and the shooting of Festen by Nimbus and The Idiots by Zentropa began in the following months.

Something new

Trier’s speech at the end of the fifth episode of The Kingdom, made in 1997 when Trier was preparing The Idiots, can be understood as a reflection on the reception of the Dogme project by the film establishment:

Taste and habit go hand in hand, but letting them run away with us will do us no good. But if we can relinquish just once what has comforted us most and filled us so many times before and if we are able really to say good-bye, perhaps the result will then be a merry wee hello to something new, unlike the old and not tasting like the old, and for precisely that reason not so bad at all.35

The situation is not without a certain irony: in a nation like Denmark where the state is the main supporter of culture and arts, it is a characteristic problem that the artistic challenge to the establishment must be made with the support of that very same establishment.

The Danish Film Institute, responsible for distributing Danish state support for film production and film culture, was established in 1972 (based on the Film Foundation of 1965) under the Ministry of Culture and has played an absolutely crucial role in the development of modern Danish cinema. The later Dogme films would be supported according to normal procedure. But it is a curious fact that Danish Film Institute did not participate in this most decisive event of new Danish cinema. It missed the opportunity perhaps because the structure of a bureaucratic institution will inevitably be unfit to handle a principally non-bureaucratic concept, but also because the institute in 1995-97 (under a temporary general manager, Mona Jensen) was in a period of transition and restructuring.

From 1998 Henning Camre, as the new CEO for the Danish Film Institute, would for nearly ten years be the powerful motor behind Danish cinema, implementing new laws and achieving considerably higher state support for Danish film production. Camre had been the Principal of the Danish Film School when Trier was a student there, and is depicted sarcastically in the autobiographical script that Trier, under the pen name of Erik Nietzsche, wrote about his film school years: De unge år (The Early Years, 2007, directed by Jacob Thuesen). Camre would represent a professionalization of Danish cinema, turning it away from experimental art film and toward general, efficient mainstream cinema – a direction antithetical to Dogme!

Ten films

Festen and The Idiots were finished in early 1998 and both films were selected for the main competition in Cannes whose leader, Gilles Jacob, had always admired Trier. It is very likely that the huge breakthrough of Dogme came from this double exposure.36

Festen won The Jury Prize in Cannes and twelve other foreign prizes and Vinterberg was declared European Discovery of the Year by the European Film Academy. If Dogme had not had this unique platform, at the world’s prime film festival, and thus the opportunity to address the entire international (art) film world, Dogme might have remained a local sport for Trier and a few selected colleagues.

At the presentation of the manifesto in 1995, the reaction had been mildly humoristic. Now, with the two first films (soon to be followed by Dogme #3, Søren Kragh-Jacobsen’s Mifune sidste sang (Mifune, 1999), which won the Silver Bear in Berlin early the following year), Dogme showed the potential of actually demonstrating a new approach to filmmaking. Of course, there were still sarcastic and condescending comments about the project as such,37 but there was no doubt that Dogme and the New Danish Cinema had found a brand that got the attention of the international film world.

In the following years, ten Danish Dogme films were produced. After Festen, The Idiots and Mifunecame Kristian Levring’s The King Is Alive (2000), Lone Scherfig’s Italiensk for begyndere (Italian for Beginners, 2000), Åke Sandgren’s Et rigtigt menneske (Truly Human, 2001), Ole Christian Madsen’s En kærlighedshistorie (Kira’s Reason – A Love Story, 2001), Susanne Bier’s Elsker dig for evigt (Open Hearts, 2002), Natasha Arthy’s Se til venstre, der er en svensker (Old, New, Borrowed and Blue, 2003), and as the last, Annette K. Olesen’s Forbrydelser (In Your Hands), which premiered in January 2004.

Dogme’s success was not least that it stood out as an experiment in art film. “The Dogme films are thought to have a broad appeal”, Trier wrote, “but they are not thought to be commercial in that sense; it is the cultural political manifestation that is the objective!”38 Though the Dogme concept enjoyed general attention abroad, only a few of the Dogme films had a larger contact with international audiences – mainly The Idiots, Festen, and Italian for Beginners.39

Dogme was a successful attempt to combine art film initiatives with mainstream accessibility. But obviously the best-selling films, also locally, were the most mainstream ones; the more arty film, the poorer the box office sales.40

Global Dogme

It was crucial to Trier that Dogme was an international movement, but also that it had started in Denmark: “We have followers in France, Sweden and Poland. But we have made it a condition that we are the first to produce, since the concept must appear to be Danish,”41 he wrote.

Approximately thirty non-Danish Dogme films received certification from the Dogme Secretariat, established in 1999 by Zentropa and Nimbus to administer Dogme.42 The Secretariat closed in 2002 and in 2005 (on March 20, precisely 10 years after the Paris presentation) Dogme was set free in a statement signed by the four Dogme brothers: “From now on the certificate, along with the manifesto and the vow of chastity, will be available on the Internet for anybody who wishes to make a Dogme film. Whether the result is a Dogme film will be up to its maker … and his or her conscience …”43 Later many Dogme films were announced on the Internet, some were even sent to the University of Copenhagen, but most were more or less amateurish short films, and undoubtedly many were non-existent, just empty titles mocking Dogme or Trier. It should be noted that this new Dogme freedom was never used by Danish filmmakers.

It has been seen as “a bit of a mystery,”44 why hardly any of the non-Danish Dogme films got any attention. But there was an important difference. The Danish films were made at the invitation of Zentropa/Trier & Nimbus/Vinterberg to carefully selected, talented people. The non-Danish Dogma filmmakers were not selected, few of them had an impressive background, some were amateurs, and only very few of them, perhaps only Harmony Korine with Julien Donkey-Boy (1999), would be considered important filmmakers. Several well-known directors were approached and invited to make a Dogme film in 1998-99, among them Andrzej Wajda, Akira Kurosawa, Aki Kaurismäki, Ingmar Bergman; and Vinterberg had breakfast with Steven Spielberg in Hollywood and invited him to join the movement.45 But they all declined.

Branding Denmark

The Dogme manifesto had taken the French New Wave as a starting point, claiming that this movement had failed: it had “proved to be a ripple that washed ashore and turned to muck.” But how did Dogme, presenting itself as a “rescue action”, manage in comparison to its predecessor? What did Dogme accomplish, one could ask?

It must be admitted that Dogme did not create a new international movement which, after all, the French New Wave had done. Dogme was an idealistic invitation on a global level, but it must be observed that the obvious talents in the film world never embraced it.

Dogme, however, may have stimulated the indie film world, both in the US (films like Keane, 2004, Shortbus, 2006, and Rachel Getting Married, 2008) and in Asia (Monsoon Wedding, 2001), and influenced films by well-established filmmakers such as Spike Lee’s Bamboozled, Mike Figgis’ Time Code (both from 2000), Steven Soderbergh’s Full Frontal (2002), and perhaps also the famous Blair Witch Project (1999). But there was, of course, already a long tradition, not least in the US, of minimalist cinema like John Cassavetes (Shadows, 1959; Husbands, 1970), whom Trier admired, Jim Jarmusch (Stranger Than Paradise, 1984), Hal Hartley (Trust, 1991), and Kevin Smith (Clerks, 1994) as well as the Belgian Dardenne brothers who had started with handheld ascetic cinema style back in the 1980s.

Dogme’s most obvious accomplishment then was that it directed international focus to new Danish cinema, branding Denmark as a film nation in a way not seen before. From an international point of view (according to textbooks and encyclopedias), Danish cinema had in the past been noted for a brief ‘golden age’ in the silent years, approximately 1910-14, with film makers such as Benjamin Christensen and stars Asta Nielsen and Valdemar Psilander; and Carl Theodor Dreyer, with his silent work in the 1920s, not only in Denmark, Sweden and Norway, but also in Germany and France (The Passion of Joan of Arc/La passion de Jeanne d’Arc, 1928), and his few but outstanding sound films over the next four decades – Vampyr (1932), Vredens Dag (Day of Wrath, 1943), Ordet (The Word, 1955), and Gertrud (1964) – was acknowledged as a great classic auteur and the only obligatory Dane in the international canon.

In more recent times, Danish cinema had only a very limited impact on the international film world. Denmark got attention in 1969 as the first country to abolish laws against pornography and in the 1980s, two Danish films received Academy Awards as Best Foreign-Language Film, Gabriel Axel’s Babette’s Feast and Bille August’s Pelle Erobreren (Pelle the Conquerer, 1987), both rather conventional cultural heritage films based on classical Danish literature. Trier, with his English-language films and his status as a leading new auteur, had already enjoyed international attention, especially with Breaking the Waves (1996). But it was Dogme that drew attention to new Danish cinema in a broader respect, making Dogme one of the most successful cultural brands from Denmark ever that also stimulated international interest in Danish cinema also after the end of the Dogme years. Since the Dogme breakthrough there has been continuous international attention to Danish cinema, much more than a nation of 5.5 million and producing an average of twenty feature films a year could expect.46

An important symptom of Dogme’s success, and perhaps the most striking proof of it, is the wealth of articles and books that focus on Dogme, attracting much more attention than any other subject in Danish cinema. There are nine books on Dogme in English, German, and Italian (and two in Danish)47 and Dogme is featured in at least six monographs on Lars von Trier.48 Dogme has become a standard academic field of research, presented in numerous book length studies, papers and dissertations.49

Most significant, perhaps, is the fact that much-used film handbooks and film history textbooks in English have institutionalized Dogme as an important movement in contemporary world cinema.50 All of the ten Danish Dogme films are included in Time Out Film Guide (ed. John Pym, 5th ed., 2007). Even Ephraim Katz’ well-known The Film Encyclopedia, with its idiotic mistake of placing Lars von Trier as a Swedish director (with no entry of his own, only mentioned in the article on Sweden!), has at least in a later edition included an article on Dogme – here called Dogme 75 (sic).51

More money

Dogme branded Danish cinema, but it was also the breakthrough for the companies behind it. When Zentropa was established in 1992 the idea was to challenge the tired old companies, especially Nordisk Film, where Trier’s and Aalbæk’s collaboration had started with the English-language Europa(1991). During the following years, Zentropa tried energetically and in a variety of business engagements to find new ways to make films. But for several years Trier’s films were the only successful productions from Zentropa.

With the breakthrough of Dogme, Zentropa, assisted by Nimbus – established 1993 and producer of Festen and Mifune and later the Dogme films by Ole Christian Madsen and Natasha Arthy – finally stood out as a center of innovative art film production. It was Dogme that branded Zentropa as the European company where new and daring ideas were developed.

In a national context Dogme undoubtedly contributed to the growing respect that Danish films enjoyed both with the audience and with the politicians. The state subsidy given to Danish film increased and a new institutional structure was introduced in 1999. In 1995-1998, the yearly budget for development and production totaled about 100 million Danish kroner; beginning in 1999, there was substantial growth to 144 million; in 2000 to 165 million; in 2001 to 224 million.52

Professor Ib Bondebjerg, who was head of the Board at Danish Film Institute during the establishing of the new order, says:

The pressure to get increased means for Danish film starts about 1990 – that is after the Academy Award and Cannes breakthrough for Gabriel Axel and Bille August. But because it demands a highly increased culture budget and a change of the customary relations between grants to various cultural areas, it takes time. (…) The whole start-up began long before Dogme, but just as it is about to be realized comes Dogme and that doesn’t make it more difficult, you can say.53

Of course, there were other success factors than Dogme. But the Dogme films (and Trier) had more press internationally, and received more prizes and attention, than other films of the period. And even though the breakthrough of Dogme took place without the support of Danish Film Institute, the Institute soon – with delayed enthusiasm – participated in and supported the success.

Dogme echoes

In the Dogme years and afterwards, other Danish films would in various ways borrow some of the Dogme elements. There were intimate dramas with focus on the characters/actors, on psychology rather than “superficial action”, such as Jesper W. Nielsen’s Okay (2002) and Annette K. Olesen’s Små ulykker (Minor Mishaps, 2002).

Nordisk Film, the veteran Danish film company, presented in 2003 their own concept of fast produced low-budget films, the so-called Director’s Cut program (sarcastically described among film people as “Dogme without rules”). It was developed by Swedish director Åke Sandgren, who had made the Dogme film Et rigtigt menneske (Truly Human, 2001) together with scriptwriter Lars Kjeldgaard. The philosophy behind Director’s Cut was: ”the cheaper the film, the better the film.”54 Sandgren says:

The idea behind Director’s Cut is that the whole process around making a film should be speeded up. The shooting should take about six weeks and take place in the real world so we avoid all the costly sets. But contrary to Dogme we have made no limitations in our concept other than it must be cheap. So we love all the modern technique that can help us make spectacular films.55

It resulted in four Danish films and one Swedish.56

Later the traditional divide between mainstream and art film was used satirically as the theme in a popular comedy Sprængfarlig bom (Clash of Egos, 2006, director Tomas Villum Jensen), written by Anders Thomas Jensen, who was writer on Mifune, The King Is Alive, and Open Hearts. Here the arrogant art film director (played by Nikolaj Lie Kaas from The Idiots), who makes allegorical art films with a shaky camera, is confronted with the common man, the angry moviegoer who wants his money back.

The plot is allegorical of the paradoxical situation in Danish cinema. Following the breakthrough of Dogme and all the international attention it got, Danish cinema moved in the opposite direction, towards a Hollywood-inspired professionalism. The Dogme wave faded out, the hysteria was over and everything was back to normal. Since Dogme Danish cinema has generally shown a return to the mainstream, also in the further careers of the Dogme directors.

Back to normal

For Vinterberg, the breakthrough with Festen was a mixed blessing. He proceeded by making art films, daring attempts like the complex melodrama It’s All About Love (2003) followed by Dear Wendy(2004), with a script by Trier. But they were unsuccessful, both commercially and critically.

Only with Jagten (The Hunt, 2012), inspired by the humanistic realism of his early work, was Vinterberg finally, 14 years after Festen, back in the front row of European cinema (Mads Mikkelsen won as best actor in Cannes and the script won the European Film Award). Where Festen tells the story of a man whose sexual abuse of his children has been undetected for years, The Hunt like an echo of the Dogme film tells the story of suspicions of sexual abuse against a man who is totally innocent. Vinterberg says:

"Let me start by saying that as a starting point and long into the process I considered, almost scientifically, The Hunt as a mirror image of Festen, an anti-thesis. You can call it symmetrical (…). And even if The Hunt looks totally different visually, we attempted the same nakedness as in Festen."57

The Hunt is symptomatic of the legacy of Dogme, a kind of mainstream variation on Dogme. The film doesn’t follow the Dogme rules, neither the production rules nor the content rules. It has ‘superficial action’ in the violent scenes, but there is an overall Dogme feeling, the “nakedness,” that Vinterberg talks about, a realistic, quite ascetic style without any excess such as special effects or epic elements.

The pattern of returning to mainstream continues with the other Dogme directors. Søren Kragh-Jacobsen, the most experienced and most traditional of the Dogme directors, continued with the English language feature Skagerrak (2003), worked on several Danish TV series and made two thrillers, Det som ingen ved (What No One Knows, 2008) and I lossens time (In the Hour of the Lynx, 2013). Kristian Levring made The Intended (2002); like his Dogme film The King Is Alive it is a story about travellers in exotic milieu, followed by the Danish thriller Den du frygter (Fear Me Not, 2008, with Festen’s Ulrich Thomsen) and the English-language Western The Salvation (2014). Lone Scherfig, whose Dogme film Italian for Beginners was one of the all-time most successful Danish films and also one of the best selling Danish films internationally, continued with art films like Wilbur Wants to Kill himself (2002), a Danish production shot in Scotland with a Scottish cast, followed by the Danish-language film Hjemve (Just Like Home, 2007), an ensemble film about a Danish provincial town not without touches of Dogma atmosphere. Both films were received with moderate enthusiasm, before she successfully turned to mainstream cinema with the Oscar-nominated An Education, followed by the less successful but equally mainstream feel-good-film One Day.

Susanne Bier’s early work – features like Freud flytter hjemmefra (Freud Leaving Home, 1991), Det bli’r i familien (Family Matters, 1994), and Pensionat Oskar (Like It Never Was Before, 1995) – connected to European art film traditions, but after her breakthrough with the mainstream comedy The One and Only (Den eneste ene, 1999) and the Dogme film Open Hearts, she became more and more mainstream. Her later films have obvious connection to Hollywood standards and were also welcomed in the US. Brothers (Brødre, 2004, was remade in the US (by Jim Sheridan, 2009), Efter brylluppet (After the Wedding, 2006, was nominated for an Academy Award and In a Better World(Hævnen, 2010) won the Oscar as Best foreign-language film. But ironically her first American production, Things We Lost in the Fire (2007), had only moderate commercial success in the US.

Ole Christian Madsen, whose Dogme film En kærlighedshistorie (Kira’s Reason, 2001) was a psychological study of a woman under the influence, continued with Nordkraft (Angels in Fast Motion, 2005), a film about drug addicts influenced by Trainspotting (Danny Boyle, 1996), and Prag (Prague, 2006), a chamber play about a marital crisis, both with an art film sensibility. He then turned mainstream with the successful period drama Flammen & Citronen (Flame and Citron, 2008), about resistance fighters during the Nazi occupation of Denmark, and the comedy Superclásico! (2011). His latest work is two episodes on the HBO series Banshee (2013, where Ulrich Thomsen has a leading role).

Natasha Arthy has made the mainstream youth feature Fighter (2007) and some TV work. Annette K. Olesen, after her Dogme film Forbrydelser (In Your Hands, 2004), made two more art films, 1:1(2006) and Lille soldat (Little Soldier, 2008), with sharply declining box office success, before she turned to mainstream. The environmental thriller Skytten (The Shooter, 2013), however, failed to find a mainstream audience.

With The Hunt Vinterberg, after unsuccessful English-language endeavours, is back in shape. This points to a language issue in Dogme and the fame it accomplished for the filmmakers. Dogme gave Danish cinema international attention, but when the Dogme directors tried going international (= English-language), it didn’t work. Lars von Trier, of course, had successfully pursued this international inclination from the beginning of his career (his first feature, The Element of Crime (1984), was an English-language production). Dogme’s success inspired Danish filmmakers and producers to think big and international, a temptation that from time to time has appeared in the small Danish film industry, but nearly always without success.

In the years after the Dogme breakthrough came films such as Vinterberg’s It’s All About Love and Dear Wendy, Scherfig’s Wilbur Wants to Kill Himself, Kragh-Jacobsens Skagerrak, and Refn’s Fear-X(2003) and, all Danish produced and English language and all of them more or less unsuccessful. Still today, Danish directors are attracted to try their luck in the international English-language film world: not only Bille August and Ole Bornedal whose experiences in this field go back to the 1990s, but Susanne Bier, Niels Arden Oplev, Asger Leth, and Christian E. Christiansen have also made American films.

In 2013 a new company, Creative Alliance, was established by Vinterberg, Scherfig, and Madsen as well as director Per Fly, Icelandic Dagur Kari, documentary filmmaker Janus Metz and producer Lars Knudsen. The plan is to prepare and support American productions by Danish filmmakers. The global dream continues.

The usual exception

While the Dogme directors generally let go of the more experimental art film and ended up making conventional mainstream productions, the exception to this tendency is, of course, Lars von Trier himself who has continued with his eccentric art film experiments, made possible by his status in the international art film world. For Trier, Dogme was only one among many initiatives. Dogme should stay a possible cure, thought Trier; the filmmaker could “take a little Dogme pill and feel much better afterwards.”58 His principle has always been – in Blake’s words – to “create your own system”, rather than “be enslaved by another man’s.”

Related to Dogme – but not considered Dogme by Trier himself59 – is D Day (2000), made by the four original Dogme brothers in co-operation as four parallel one-shot films, shot live on New Year’s Eve 1999 and shown the following evening on four different TV channels that the audience could switch between.60

Trier is a distinctive auteur, doing his own eccentric work. But he has also, contrary to most eccentric auteurs, tried to implicate others, to create a milieu, a creative collective. Examples include Zentropa and Dogme, as well as the concepts of his Open Film City manifesto61 with its vision of a milieu where creative film people could work together and meet each other at least in the shared canteen, and Armybase.com, a never materialized Internet project, where the idea was to take the mystery out of the film production via a home page, making the process accessible to the public:62 These are all initiatives that, more or less successfully, invite the group, the team. Very suitably Trier’s The Idiots is about a collective, a group, a mini-society that play together, perhaps for fun, perhaps for real.

Trier’s preference for rules and constraints continues in Dancer in the Dark (2000), with the use of one hundred stationary digital cameras; in The Five Obstructions (De fem benspænd, 2003), where Trier improvises a special set of rules for mentor Jørgen Leth, and in Dogville (2003) with its stage floor painted with white lines instead of sets. Direktøren for det hele (The Boss of It All, 2006), originally presented by Trier as a second Dogme film,63 had its so-called ‘Automavision’ where the shots are chosen randomly by a computer. The shaky visuals in handheld Dogme style are back both in Antichrist (2009), where the style ended up not being ugly enough for Trier who subsequently stopped his collaboration with cinematographer Anthony Dod Mantle,64 and in Melancholia (2011), and in both films contrasted with a formalistic, magical style in some haunting sequences.

The next generation

Dogme was a club that chose its own members; an invitation, but also an exclusion, and the young generation did not necessarily feel that Dogme was an interesting way for them to go. But then Dogme could be useful a concept to kick against.

Nikolaj Arcel, the most successful of the younger directors, clearly marked the distance to Dogme with his first feature, the political thriller Kongekabale (King’s Game, 2004). This film was made in faultless Hollywood style as was his children’s thriller De fortabte sjæles ø (The Island of Lost Souls, 2007) and his historical drama En kongelig affære (A Royal Affair, 2012) which was nominated for an Academy Award in 2013). In Sandheden om mænd (Truth about Men, 2010), a self-ironical and more or less autobiographical story in auteur style about the crises in the personal and professional life of a disillusioned scriptwriter, the protagonist asks himself, referring to the famous scene in Festen: “Why wasn’t it me who made up the green and the yellow speech?!”

It is especially the young generation of filmmakers within the art cinema who have problems finding an original alternative way, at the same time as art film generally is under pressure during the current economic low. And it is not so easy when Trier, now in his mid-50s, still is the nation’s most avant-garde filmmaker, the most daring experimentalist.

Christoffer Boe, who together with Simon Staho (who has made his most important work in Sweden) is the leading art film director of the younger generation, received the Camera d’Or for his first feature in the Director’s Cut program, Reconstruction (2003), co-written with ‘Dogme doctor’ Mogens Rukov, co-author of Festen and Kira’s Reason. Boe’s later feature Offscreen (2006), where the protagonist tells his story about a failed marriage and a descent into insanity by constantly carrying a camera with him, was not without elements of Dogme style. Boe’s films, exploring new territories for the avant-garde, were seen by a small and decreasing audience, and now he has also turned to mainstream with the successful biopic Spies & Glistrup (Sex, Drugs & Taxation, 2013).

The art film crisis can also be seen by the fact that Zentropa announced in February 2008 that the ‘arch enemy’ Nordisk Film (owned by media conglomerate Egmont) had bought half of its shares and thereby control over Zentropa. In 2012, the era of risky experiments was definitively over. Zentropa, having established its reputation as a pioneer of art films and daring innovation, now announced that it was time to play safe. “We would certainly not have made Susanne Bier's first film today. And for that matter, nor Thomas Vinterberg's,” Peter Aalbæk Jensen said.65

Vinterberg, in his analysis of the current situation in Danish film, looks back on Dogme:

There is a kind of clearing out. All the ‘misfits’ disappear. Aalbæk doesn’t dare to do the ‘misfits’ anymore, because he’s afraid of going broke. I understand him well. But the misfits have to be somewhere. Lars was also a ‘misfit’ once. We are precisely where we were when Trier and I began doing Dogme. Totally. Everything is rotten, but quite efficient.66

But there are still tendencies in contemporary Danish film that point back to Dogme. The handheld, sketchy raw realist and ‘anti-aesthetic’ style has been adopted by documentaries that overlap with fictional narratives such as Sami Saif & Phie Ambo’s Family (2001), Pernille Rose Grønkjær’s The Monastery (2006), and Janus Metz’s Armadillo (2010).

Linda Wendel, who after a number of films in the 80s and 90s had problems getting support from the Danish Film Institute, chose to make small no-budget films, often shot in her own apartment. One Shot (2008), a 78-minute film in one shot, about a mother, her lover and her daughter, has an unmistakable Dogme look.

Traces of Dogme are most obvious in the work of Michael Noer and Tobias Lindholm, perhaps the most promising new talents of their generation. Together they directed the prison drama R (2010); then Lindholm made Kapringen (A Hijacking, 2012) and Noer Nordvest (Northwest, 2013). They have, not without subtlety, named their method/concept Reality Rules, using authentic locations and a mixture of amateur and professional talent. “We stand on the shoulders of Dogme”, says Lindholm, who also co-wrote Vinterberg’s The Hunt:67

I can certainly confirm Dogme’s decisive importance for the thoughts behind R and A Hijacking and Reality Rules. We never wrote a real manifesto but have only made the rule that means that our thoughts and ideas always must be tested by reality … if it doesn’t belong in reality it doesn’t belong in our film.68

Liberation and legacy

Dogme came as a reminder of the possibilities and the potentials of letting go of the technological illusions. It was an initiative of purification, simplification, of turning away from the opulent technical virtuosity of filmmaking and approaching a simple, ascetic method. Poor and pure.

But the minimalist approach can hardly be said to have conquered the film world. Technical perfectionism and the illusionary techniques – such as CGI and 3D – are becoming more and more central to the mainstream industry. Not so surprising, since attracting the audience with awe-inspiring tricks and illusions always has been a major part of the film business.

Dogme can hardly be said to have had a decisive and permanent influence on the film world. But the concept and the philosophy of Dogme, more than the actual results, made an impact, not least setting the international agenda in the aesthetic and theoretical debates where it found surprising resonance that seems to continue. And Dogme branded Denmark as a modern film country and promote Danish film in a degree not seen before: a small nation with global influence.

Dogme was a breath of fresh air in Danish cinema in the late 90s, it came with innovation and originality (though some of the films actually were less original than they seemed).69 With its strict rules and prohibitions, Dogme worked as a liberation, setting free creativity and giving Danish cinema a boost of buoyancy, an optimism and self-confidence, even though the method itself had only a limited effect. It was a group endeavor, but also a solitary experiment with freedom and control.

And when Festen won a Bodil, the oldest Danish film prize, Vinterberg acknowledged his mentor: “We can’t get away from the fact that it is Lars who invented the whole thing. It is he who has given us wings.”70

Now Danish cinema is back on the solid ground again, but once it was flying.

BY: PETER SCHEPELERN / LEKTOR / INSTITUT FOR MEDIER, ERKENDELSE OG FORMIDLING / KØBENHAVNS UNIVERSITET

Notes

1. Often erroneously written: Dogme95, see Kelly; Badley; Mast & Kawin.

2. Stefan Volk, FILM-DIENST, 2005 no. 8.

3. Björkman 2002, 50.

4. Conversation with Trier (date confidential).

5. Schepelern 2000, 171 ff.

6. See Bainbridge, 167 ff.

7. H.G. Pflaum & H.H. Ptrinzler: Cinema in the Federal Republic of Germany, 1983.

8. Of film manifestos, see Schepelern 2005 a; MacKenzie in Hjort and MacKenzie; Bainbridge. See also: Film Manifestos and Global Cinema Cultures: A Critical Anthology, ed. Scott MacKenzie (2014).

10. See Roman, 67, 88; The Purified.

11. See Björkman 2002, 20; Björkman 2003, 202.

12. Richard Porton, CINEASTE 1999, no. 2-3,.

13. Hjort and Bondebjerg, 210.

14. Müller, 258, note 44. (My translation).

15. See Claus Christensen in Hjort and MacKenzie.

16. See Björkman 2002, 24, 28, 40, 44.

17. Trier to Hilden, November 21, 1996. DFI archive.

18. Björkman 2003, 214 f.

19. Kelly, 138.

20. Björkman 2002, 21.

21. Conversation with Vinterberg (November 15, 2012).

22. See Bainbridge, 83; Cook, 568; Cousins, 461; Gomery and Pafort-Overduin, 377.

23. Conversation with Vinterberg (November 15, 2012).

24. Schepelern 2005 b.

25. Trier had originally wanted Nils Malmros to participate – young Trier had been an assistant on Malmros’ Tree of Knowledge (Kundskabens Træ, 1980), cf. A. Addonizio et al.: Il Dogma della Libertà, Palermo: Battaglia, 1999, p. 26; Aalbæk wanted Bille August, cf. Björkman 2002, p. 51, but without result.

26. Politiken, March 18 and 25, 1995.

27. Piil, “Triers løfte”, Information, March 21, 1995. Later, in 2002, he regretted his attitude, cf. Piil: Film på hjernen (Information, 2003), 661.

28. Error in Stevenson; see French Ministry of Culture (ed.): Le Cinéma vers son deuxième siècle: colloque international, 20 et 21 mars 1995, Odéon-Théâtre de l'Europe, Paris: Le Monde Editions, 1995.

29. See Hjort and MacKenzie.

30. Trier to Hilden, August 14, 1995 and November 21, 1996. DFI archive.

31. November 21, 1996. DFI Archive.

32. Trier to Hilden, November 21, 1996. DFI archive.

33. Trier to DFI, January 8, 1997. DFI archive.

34. Conversation with Bjørn Erichsen (March 13, 2013).

35. The Kingdom II, episode 5: 1:01:51-1:02:19; see Jørholt, 78.

36. See Birgitte Hald in Björkman 2002, 48; Björkman 2003, 217.

37. Roman Polanski, in an interview at The Danish Film School, November 17, 1999, claimed that his little daughter had made similar films.

38. Trier to Hilden: November 21, 1996. DFI archive.

39. Most successful at the international markets were The Celebration and Italian for Beginners each with 2.1 million admissions (outside Denmark), The Idiots with 717.000 and Mifune with 709.000. Cf. Facts & Figures 2007 Danish Film Institute; http://www.dfi.dk/Tal-og-fakta/Noegletal.aspx.

40. Danish figures: Italian for Beginners – 818.835; Open Hearts – 502.236; The Celebration – 360.000; Mifune – 350.871; Old, New, Borrowed and Blue – 157.974; In Your Hands – 131.445; The Idiots – 120.000; Kira’s Reason – 63.293; Truly Human – 53.788; The King Is Alive – 13.233.

41. Trier to Hilden: August 14, 1995. DFI archive.

42. Certificate, see Roman, 100.

43. Schulte, 207. The text was written by Schepelern, listed at the homepage as academic adviser.

44. Stevenson in Lorenz, 2.

45. See Stevenson, 74; Björkman, 202; Schepelern 2012.

46. Bier’s After the Wedding and Arcel’s A Royal Affair were Academy Award nominees, and Bier’s In a Better World won the Award (2011), as did short fiction films Election Day (Valgaften, 1998) and This Charming Man (Der er en yndig mand, 2002).

47. Roman; Kelly; Stevenson; Hallberg and Wewerka; Schulte-Eversum; Lorenz; and A. Addonizio et al.: Il Dogma della Libertà (Palermo: Battaglia, 1999); Tina Porcelli: Lars von Trier e Dogma (Milano: Il Castoro, 2001); Matteo Lolletti and Michelangelo Pasini: Purezza e castità (Forlì: Foschi, 2011); Koutsouraki (2013).

48. Achim Forst: Breaking the Dreams: Das Kino des Lars von Trier (Marburg: Schüren, 1998); Schepelern 2000; Jack Stevenson: Lars von Trier (London: BFI, 2002); Bainbridge; Müller; Jean-Claude Lamy: Lars von Trier: Le provocateur (Paris: Grasset, 2005); Badley; Jan Simons: Playing the Waves: Lars Trier’s Game Cinema (Amsterdam University Press, 2007).

49. Cf. Hjort & MacKenzie (2003); Hjort (2005); Schepelern (in Nestingen/Elkington, 2005); Margarita Ledo (2004); Shohini Chaudhuri (in Nicholas Rombes, ed., 2005); Hanna Maria Laakso (2007); Thomas Christen (in Christen & Robert Blanchet, 2008); Henriette Bornkamm (2008); René Prédal (2008); Fernando Ramos Arenas (2011); Markus Kuhn (2011); Claire Thomson (2013); Koutsourakis (2013).

50. Cook; Cousins; John Orr In Elizabeth Ezra (ed.): European Cinema (Oxford University Press, 2004); Virginia Wright Wexman: A History of Film (6th ed., Allyn & Bacon, 2005); Richard Armstrong’s The Rough Guide to Film (London: Rough Guides, 2007); Richard Kelley In Pam Cook (ed.): The Cinema Book (London: BFI, 2007); Paul Grainge; Mark Jancovich, Sharon Monteith: Film Histories(Edinburgh University Press, 2007); Mast and Kawin; Timothy Corrigan & Patricia White: The Film Experience (2nd ed., Bedford: St. Martins, 2008); Thompson and Bordwell; Gomery and Pafort-Overduin.

51. 6th ed., revised by Ronald Dean Nolen (London: Collins, 2008).

52. Resultatkontrakt 1999-2002; Virksomhedsregnskab 1998, Det Danske Filminstitut. DFI, digital archive.

53. Email to author (April 18, 2013).

54. “Billigt er bedre”, Ekko no. 23 (2004).

55. Berlingske Tidende, September 22, 2003 http://www.b.dk/kultur/billige-film-har-succes

56. Director’s Cut resulted in four Danish films and one Swedish: Christoffer Boe’s Reconstruction(2003); Morten Arnfred’s Move Me (Lykkevej, 2003); Åke Sandgren’s Flies on the Wall (Fluerne på væggen, 2005), Jacob Thuesen’s Accused (Anklaget, 205), and Daniel Espinosa’s Swedish The Babylon Disease (Babylonsjukan, 2004).

57. Schepelern 2012.

58. Hjort and Bondebjerg, 222.

59. Kelly, 136.

60. See Martin Roberts in Hjort & MacKenzie.

61. See Hjort & Bondebjerg, 224.

62. http://www.information.dk/31396.

63. Information 13.5.2005, Christian Monggaard.

64. See http://scsmi09.mef.ku.dk/uploads/AntichristTrier.pdf/

65. Kim Faber & Mikkel Vuorela, May 12, 2012,

http://politiken.dk/kultur/film/ECE1623448/filmselskaber-toer-ikke-satse-paa-nye-stjernefroe

66. The Danish word 'bastard' is difficult to translate directly as it is quite a strong swear word in English. The Thomas Vinterberg quote in Danish: ”Der sker en form for oprydning. Alle bastarderne forsvinder. Aalbæk tør jo ikke lave bastarderne mere, fordi han er bange for at gå konkurs. Jeg kan godt forstå ham. Men bastarderne er nødt til at være et eller andet sted. Lars var også en bastard engang. Vi er lige præcis der, hvor vi var, da Trier og jeg gav os til at lave dogme. Fuldstændig. Alt er røvsygt, men ret velfungerende.”. Schepelern 2012.

67. Conversation with Lindholm (September 4, 2012).

68. Email to author (April 8, 2013).

69. Both The Celebration and Italian for Beginners had borrowed from sources that are not mentioned in the credits. The Celebration was closely based on a documentary radio programme (in the series Koplevs Krydsfelt, DR, March 28, 1996) that eventually turned out to be fiction (cf. Thomson; Claus Christensen: “Der var engang en fest”, http://www.ekkofilm.dk/artikler/der-var-engang-en-fest/); Italian for Beginners had some, very limited similarities to the novel Evening Class(1996) by Irish writer Maeve Binchy; it concerns only the basic concept – a handful of people, all in need of love, meet in an evening class in Italian – but Zentropa later made a settlement with the writer (cf. Rasmus Strøyer: “Lone Scherfig stjal idé til “Italiensk for begyndere”, http://www.dr.dk/Nyheder/Kultur/2010/05/17/143104.htm). It can also be mentioned that Kira’s Reason has evident similarities with Cassavetes’ A Woman Under the Influence. And the scene in Truly Human by Swedish director Åke Sandgren where children in an elevator suddenly burst into song seems inspired by a similar scene in the subway in Swedish Roy Andersson’s Songs from Second Floor (2000, Sånger från andra våningen).

70. Berlingske Tidende, March 8, 1999.

References

Arenas, Fernando Ramos. 2011. Der Auteur und die Autoren. Leipzig: Leipziger Universitätsverlag.

Badley, Linda. 2011. Lars von Trier. Urbana: University of Illinois.

Bainbridge, Caroline. 2007. The Cinema of Lars von Trier: Authenticity and Artifice. London: Wallflower.

Björkman, Stig. 2002. Dogma 95: Estetik och ekonomi. Stockholm: Dramatiska Institutet.

Björkman, Stig. 2003. Trier on von Trier. London: Faber and Faber.

Bornkamm, Henriette. 2008. Bilder, die lügen...: Alte und neue Grenzbereiche zwischen Dokumentar- und Spielfilm und die Wirkung dokumentarischer Ästhetik. Saarbrücken: VDM Verlag.

Chaudhuri, Shohini. 2005. “Dogma Brothers: Lars von Trier and Thomas Vinterberg.” In New Punk Cinema, ed. Nicholas Rombes. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Christen, Thomas. 2008. “Dogme '95: Rückkehr zum Grundlegenden”: In Einführung in die Filmgeschichte: New Hollywood bis Dogma 95. Marburg: Schüren Verlag.

Cook, David A. 2003. A History of Narrative Film, 4th ed. New York: Norton.

Cousins, Mark. 2004. The Story of Film. London: Pavilion.

Gomery, Douglas and Clara Pafort-Overduin. 2011. Movie History: A Survey, 2nd ed. New York: Routledge.

Hallberg, Jana and Alexander Wewerka, eds. 2001. Dogma 95: Zwischen Kontrolle und Chaos. Berlin: Alexander Verlag.

Hjort, Mette and Scott MacKenzie, eds. 2003. Purity and Provocation: Dogma 95. London: BFI.

Hjort, Mette and Ib Bondebjerg. 2001. The Danish Directors: Dialogues on a Contemporary National Cinema. Bristol: Intellect.

Hjort, Mette. 2005. Small Nation, Global Cinema: The New Danish Cinema. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Hjort, Mette. 2010. Lone Scherfig’s Italian for Beginners. Seattle: University of Washington Press, Nordic Film Classics Series.

Jørholt, Eva. 2005. ”P.S.: Tilbageblik på Dogme 95 som kulturfænomen og (anti)æstetisk eksperiment.” In Som i et spejl, edited by Anne Jespersen and Eva Jørholt. Copenhagen: Rosinante.

Kelly, Richard. 2000. The Name of this Book is Dogme95. London: Faber and Faber.

Koutsourakis, Angelos. 2013. Politics as Form in Lars von Trier. New York: Bloomsbury.

Kuhn, Markus. 2011. Filmnarratologie: Ein erzählteoretisches Analysemodell. Göttingen: Walter de Gruyter Verlag.

Laakso, Hanna Maria. 2007. Women in the Chamber: the Influence of the Strindbergian Theatrical Legacy on Danish Dogma Films. Montreal. Concordia University. http://spectrum.library.concordia.ca/975724/

Ledo, Margarita. 2004. Del Cine-Ojo a Dogma 95. Barcelona: Ediciones Paidos Iberica

Lorenz, Matthias N., ed. 2003. Dogma 95 im Kontext. Wiesbaden: Deutscher Universitäts-Verlag.

Lumholt, Jan, ed. 2003. Lars von Trier Interviews. Jackson: University of Mississippi.

Mast, Gerald and Bruce F. Kawin. 2008. A Short History of the Movies, 10th ed. New York: Pearson.

Müller, Marion. 2000. Vexierbilder: Die Filmwelten des Lars von Trier. St. Augustin: Gardez! Verlag.

Prédal, René. 2008. Le cinéma à l'heure des petites cameras. Paris: Klincksieck.

Raskin, Richard, ed. Aspects of Dogma, [theme issue], p.o.v.: A Danish Journal of Film Studies, no. 10 (2000). Aarhus: University of Aarhus.

Roman, Shari. 2001. Digital Babylon: Hollywood, Indiewood & Dogme 95. Hollywood: IFILM.

Schepelern, Peter. 2000. Lars von Triers film: Tvang og befrielse. Copenhagen: Rosinante.

Schepelern, Peter. 2005. ”Ten Years of Dogme”, ”The King of Dogme”, ”Ten plus Three”, Film special issue/Dogme spring, 2005. (Also on: www.dfi.dk).

Schepelern, Peter. 2005 a. “Film According to Dogma. Ground Rules, Obstacles, and Liberations.” In Transnational Cinema in a Global North: Nordic Cinema in Transition, edited by Trevor Elkington, Andrew Nestingen. (Detroit: Wayne State University Press)

Schepelern, Peter. 2005 b. “Drillepinden” [interview with Lars von Trier], Ekko no. 28.

Schepelern, Peter. 2012: “En mand kommer hjem” [interview with Thomas Vinterberg], Ekko no. 59.

Schulte-Eversum, Kristina M. 2007. Zwischen Realität und Fiktion: Dogma 95 als postmoderner Wirklichkeits-Remix? Konstanz: UVK.

Stevenson, Jack. 2003. Dogme Uncut: Lars von Trier, Thomas Vinterberg, and the Gang That Took on Hollywood. Santa Monica: Santa Monica Press.

Thomson, C. Claire. 2013. Thomas Vinterberg's Festen. Seattle: University of Washington Press, Nordic Film Classics Series.

Thompson, Kristin & David Bordwell. 2010. Film History: An Introduction, 3rd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Kildeangivelse

Schepelern, Peter (2013): After The Celebration: The Effect of Dogme on Danish Cinema. Kosmorama #251 (www.kosmorama.org).